BANKING ON UNEMPLOYMENT OP-ED

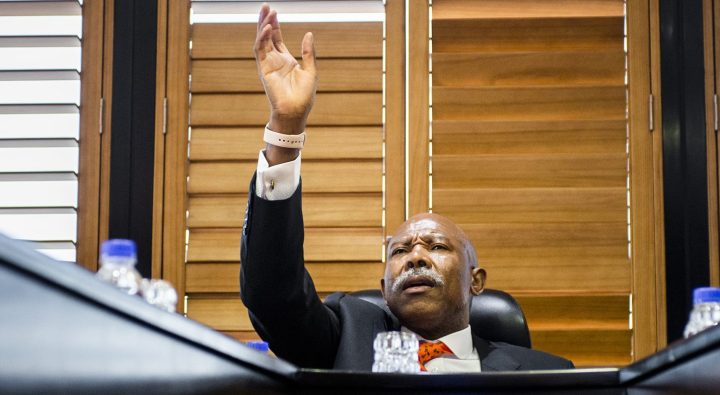

The working class is being sacrificed on the altar of Lesetja Kganyago’s battle against inflation

Instead of confronting concentration, monopoly and speculation – the real sources of this bout of inflation – central banks throughout the world, including the South African Reserve Bank, are making the working class the sacrificial lamb.

In a Q&A session with journalists after announcing the revised repo rate on 27 January 2023, South African Reserve Bank (SARB) governor Lesetja Kganyago took the opportunity to educate the nation about the intent of the drafters of the Constitution.

He lauded their infinite wisdom in identifying price stability as the indispensable precondition to “balanced and sustainable growth”.

To the charge that the Monetary Policy Committee’s (MPC) successive rate hikes prevented economic growth, and that the mandate of the SARB must be expanded to include employment creation, the governor was vociferous that job creation is not the purview of the SARB. That is, employment creation is the preserve of government policy – not the SARB.

Below we demystify the governor and the MPC’s actions. We further demonstrate that even if it were true that the SARB has nothing to do with employment, it certainly has much to do with the soaring levels of unemployment.

The governor’s smoke and mirrors, sophistry and sleight of hand

That the SARB must check persistent inflation with rate hikes is so trite that how it realises this aim is hardly interrogated. This section briefly looks at this question.

For the SARB, inflation is caused by too much money chasing too few goods. Informed by this conception of inflation, the SARB then acts to reduce money in circulation and consequently, demand in the economy, by raising the interest rate to make the cost of credit expensive. This discourages borrowing and thus curtails further increases in the money supply.

But because along with the rise in the cost of credit comes the rise in the cost of servicing debt, the result is bankruptcies and defaults for businesses and consumers. Most crucially, workers lose their jobs.

It’s here that the SARB’s policy reveals itself in all its insidiousness.

The loss of jobs because of the SARB’s policy is not an unintended consequence of that policy; the unemployed are not the collateral damage in the SARB’s fight against inflation. Rather, the Bank intentionally creates unemployment to keep rising prices in check. The working class must starve for the economy to return to full health.

If the above point provokes scepticism, then let the governor speak for himself.

Giving a lecture at the Wits School of Governance on 1 November 2022, the governor cautioned his audience about South Africa’s non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (the Nairu). In mainstream economic circles, the Nairu is what the neoliberal doctrinaires sometimes call the natural rate of unemployment – the unemployment at which inflation is stable.

The theory is: there exists a level of employment beyond which the economy cannot and must not pass. And if the employment rate were to pass that point, inflation would result, and the central bank would be compelled to intervene by raising rates to induce unemployment to levels commensurate with the Nairu.

The SARB actively creates unemployment to fight inflation. This is the standard policy of all central banks whose technocrats are imbued with neoliberal dogma.

Impoverishing the working class as the means to curb inflation was first put into effective use in the late 1970s by Paul Volcker – the then chairperson of the US Federal Reserve. For Volcker, the inflation of the 1970s reflected that the natural rate of unemployment of the US economy – the Nairu – had been passed.

Most crucially, the inflation rate was reflective of labour’s disproportionate power against capital. In other words, labour was powerful such that it succeeded in brokering wage increases that stimulated inflation.

To restore balance, and thereby discipline labour, Volcker went to work, raising interest rates all the way to 20%, leading to defaults, bankruptcies and retrenchments, and even a debt crisis for countries that had dollar-denominated debt.

Read more in Daily Maverick: SA Reserve Bank hikes repo rate by 50 basis points after inflation, rand set alarm bells ringing

In its liquidations and insolvencies statistics, Stats SA has recorded about 243 liquidations for February and January 2023. In 2022, about 1,907 businesses were liquidated. Liquidations, however, are a very conservative measure of the consequences of debt defaults, rolling blackouts and other factors affecting the health of business and the economy.

Before liquidation, there is a protracted process in which businesses become insolvent and scrabble to find solutions in paying creditors and debtors, and of reducing input costs in an attempt to return their businesses to full health. Both the process of reducing input costs and of liquidations result in retrenchments.

Though other factors result in debt and credit defaults and insolvencies for businesses, interest rate hikes are part of the main factors. In October 2022, the International Monetary Fund observed that “bankruptcies have already started to increase because of higher borrowing costs” for small firms. Therefore, the improved business debt risk amid sharply rising interest rates in the third quarter of 2022 was superficial, as the Experian Business Default Index remarked.

It is demonstrably false that the SARB has nothing to do with employment. The SARB actively creates unemployment to fight inflation. This is the standard policy of all central banks whose technocrats are imbued with neoliberal dogma. The governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) Adrian Orr explicitly revealed this brutalising policy when in November 2022 he said that the RBNZ must “engineer recession to reduce inflation”.

Concentration, monopoly and high prices

The oft-touted reasons for obstinate global inflation are that it is the after-effects of supply bottlenecks from the Covid-19 lockdowns and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which disrupted global supply chains. All this, in South Africa’s case, coupled with persistent rolling blackouts.

Some on the Left even add to the mix the Fed’s and the Bank of England’s (BOE) massive quantitative easing (QE) programmes following the global financial crisis of 2008. A classic case of the chickens coming home to roost, we are told. This is the so-called pumping of liquidity, which betrays a profound misunderstanding of not only QE but indeed of the banking system itself.

These reasons offered for this inflationary episode rest on the mistaken economic wisdom that prices of goods and services reflect supply and demand on the market. They assume a market approximating perfect competition. Of course, such fairy tales hold true only in mainstream economics textbooks. In the real world, price formation is firmly in the hands of monopolies, oligopolies and financial speculators in the commodity markets.

Global food production and distribution is concentrated in a few multinational corporations. In 1999, Cargill controlled 45% of the world grain trade, ADM controlled 30%, and Glencore and Bunge claimed the rest. These oligopolies enjoy the privilege of setting prices. They not only deal in grain, but also wheat, maize, cotton, soya and coffee, and some companies, like Glencore, even deal in petroleum and gas.

And since commodities have standardised prices throughout the world, the ever-diminishing number of corporations dealing in commodities hold the price-setting power for the rest of the globe.

We, on the other hand, contend that money expresses not only the value created by the working class, but also the value-creating capacity of the latter.

Here in South Africa, the Essential Food Price Monitoring (EFPM) report by the Competition Commission, released in March 2023, made damning revelations in which it detailed the extortionate price increases (and thus proving the price-setting powers of monopolies) in bread, sunflower oil, meat and other consumables. The report further accuses South African businesses, in their recent price increases, of raking in more profits under the cover of the much-publicised inflation, climate problems and Russia-Ukraine war. Indeed, a glance at the report shows retail prices are soaring, while wholesale prices are relatively cheaper.

Then there is speculation on food and other essential commodities like sources of energy on the financial markets. Speculation on commodities usually takes the form of futures and forward contracts. The futures contract, for instance, emerged as an ingenious innovation to hedge against the risk and uncertainty inherent in the market.

Read more in Daily Maverick: SA unemployment rate nudges down to 32.7% in Q4 2022, signalling no meaningful improvement

And the risk and uncertainty derive from capitalism as a socially unplanned system in which the production and distribution of goods and services is through the market mechanism. Ever present in the market is the threat of businesses’ failure – especially for businesses that deal in commodities whose prices fluctuate.

Therefore, to minimise the threat posed by price fluctuations, and thereby reduce the possibility of business failure, companies enter futures contracts with counterparties to lock in prices. However, with the advent of neoliberal deregulation, the futures contracts have become the basis for financial speculation.

In 1991, the investment bank Goldman Sachs created the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index Funds (now known as the S&P GSCI). The S&P GSCI converts commodity contracts into an asset that can be bought by other financial institutions. The index funds became the focus of food speculation and its profitability spurred other investment banks to create their own commodity indexes.

Now the prices of physical commodities on which the commodity futures are based depend on the speculative activities and changes in the futures markets. Financial speculation unmoored prices of actual, physical commodities from supply and demand, and anchored them on the actions of financial speculators and the performance of financial instruments.

In addition, following the global financial crisis, financial institutions flooded the futures market because the crisis had left bonds and stocks risky and unattractive to profit-seeking investors, making commodity futures attractive.

Moreover, since the influx of financial institutions into commodity futures, the futures have become monstrous in size, completely out of proportion to the physical commodities they represent, thereby causing volatility in prices.

Instead of confronting concentration, monopoly and speculation – the real sources of this bout of inflation – central banks throughout the world, including the SARB, are making the working class the sacrificial lamb.

Central banks, the value of money and the working class

What gives money its value?

For the monetarists, it is how much of it is in circulation relative to the produced goods and services. We, on the other hand, contend that money expresses not only the value created by the working class, but also the value-creating capacity of the latter. The mainstream begins with money; we begin with actual value created by the working class.

Put differently, it is the working class that underwrites and gives money its purchasing power and, most crucially, it is the working class that provides the social basis for the monopoly money-creating powers of the state through its central bank.

Read more in Daily Maverick: The social crisis of unemployment is hardwired into the fabric of our neoliberal, capitalist economy

Our contention is borne out by recent history. In every country that has had hyperinflation since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the devaluation of money has been preceded first by the breakdown in production and then followed by hyperinflation. Prime examples are Zimbabwe in the early 2000s and Venezuela recently.

If production, for whatever reason, breaks down – that is, workers cease creating value – paper money becomes worthless. This means the working class underwrites the money-creating powers of the central banks.

The irony, however, is that central banks fight inflation by displacing the very material force that underwrites money from the value-creating process. In other words, by creating unemployment through inducing bankruptcies, the central banks are muting the means of production and the labourers, whose combination creates a value-creating labour process.

Hence, we strongly argue that instead of displacing labour from the value-creating process to fight inflation, the SA Reserve Bank must institute a credit facility to assemble enterprises under the democratic ownership of the working class. That will not only power our idling industrial capacity (which sits at 21.9%, according to Stats SA) but expand it beyond its current capacity. DM

Trevor Shaku is the national spokesperson of the SA Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu). Newton Masuku is the provincial organiser of the Transport, Retail and General Workers’ Union, a Saftu affiliate.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This could have been written any time between 1935 and now. Same old same old. Capitalism is the bogie man and socialism the Robin Hood. Society is really Boys and their toys (guns) .