BUSINESS REFLECTION

After the Bell: The ragged history of the lumpenproletariat

André de Ruyter complained that the ANC still used terms like ‘comrade’ and ‘lumpenproletariat’. Is the ANC economically stuck in the past, or are these terms just historical hangovers used to signify partisanship?

In his now-famous interview on eNCA, former Eskom CEO André de Ruyter made the point that the ANC was ideologically stuck in the past and still used terms like “comrade” and “lumpenproletariat”.

Compared with the dynamite he exploded during the interview, this comment was pretty soft cheese. But on reflection, I suspect it may be more interesting than it seems. Is the ANC stuck in the past economically, or are these terms just historical hangovers, used to signify intraparty partisanship rather than ideological predisposition?

Take the greeting “comrade” for example. I kinda like it. Of course, I know, comrade has militant left connotations and therefore fits De Ruyter’s characterisation of a party with its ideological roots in 1980s Sovietism.

It also has military connotations, as in “comrade in arms”, which touches on the ANC’s view of itself as an armed liberation force. But I like its undercurrent of friendship and collegiality. And it is egalitarian, as opposed to Mr or Mrs or Ms, and so on.

The word derives from the Spanish and Portuguese term “camarada”, literally meaning “chamber mate”, or person from the same room, and its origin owes more to the French revolution than the Russian revolution.

It also shares the origin of the word “camaraderie”, which betokens mutual trust and friendship. And this is why we get the Soviet comrade, but also the Comrades Marathon. In any event, not that it’s the biggest issue in the world, but I give the ANC a free pass on the comrade greeting.

But when we venture into the world of the “lumpenproletariat”, we descend into a very dark place. Personally, I hate the word and all its implications.

‘Unthinking lower strata’

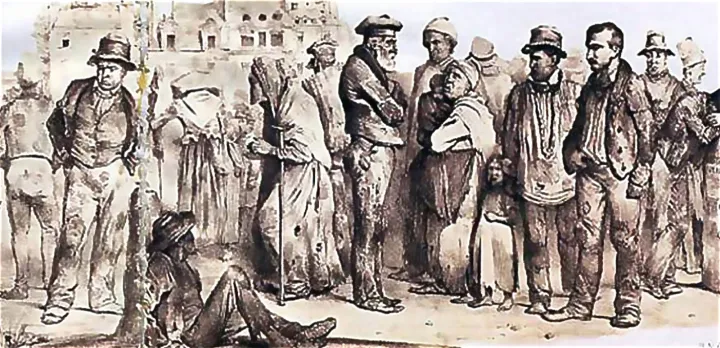

Lumpenproletariat is very specifically a phrase used by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, composed of the German word “lumpen”, which means “ragged”, and the French word proletariat. It was specifically used to connote the “unthinking lower strata of society” often exploited by notionally reactionary forces.

The description was coined mainly after the failures of the revolutions of 1848 in Europe, which were a problem for the Marxian thesis because the proletariat had somehow failed to become the inevitably victorious force Marx had designated them to be.

In trying to understand this failure while remaining consistent with the overall theory of a grand class conflict, Marx and Engels explained there was an unfortunate wrinkle in the class system: the lumpenproletariat. So that, or the theory, was wrong.

But what I object to is that the whole idea reeks of intellectual arrogance. The lumpenproletariat were often described as “beggars and thieves”. Prostitutes and sometimes intellectuals were also regarded as part of the group, and their big shortcoming was the lack of “class consciousness”.

That, of course, is another way of saying, this is a group of people who don’t agree with us, so they must be, you know, demonised.

But Marx and Engels were inadvertently undermining their own theory because if ideology is principally economically determined, which is the Marxist dogma, then how could any person who was not a member of the bourgeoisie be cast out as an upstanding member of the proletariat? Economic determinism should unfailingly provide you with class consciousness, right?

Anyway, “lumpenproletariat” has moved on from there, and is now more generally used by intellectual elites to pour scorn on people they don’t like in the culture wars.

Hence, the “deplorables” referred to by US presidential candidate Hillary Clinton are often characterised by the elite left as the “Trump-supporting lumpenproletariat”.

And I get the same whiff when I hear senior ANC members referring to poor South Africans who idiotically choose to vote for other parties.

Perceived status

My own view on the classes in society has been influenced by an enormously funny book written by American academic Paul Fussell called Class: A Guide Through the American Status System. Fussell looks at class from the point of view of perceived status rather than monetary wealth, pointing out that university professors and mechanics often earn about the same. But one drinks chardonnay and the other Budweiser; one lights candles for dinner and the other is taking apart a motorcycle where his dining room table might have been. What distinguishes the classes is not only money, but attitude.

Fussell divides American society into seven hierarchical classes: top out-of-sight, upper, upper middle, middle, high-prole, mid-prole, low-prole, bottom out-of-sight, and X – this last being the classless class (and a get-out-of-jail-free card) to which Fussell assigned himself.

He proceeds to dissect all the classes and their funny foibles, like the terrible “upper middle” preference for ties with sailing ensign designs and absurdly long, paved driveways.

Fussell dislikes the “middle” because he sees them as hypocritical, snobbish, pretentious and tasteless, mainly because they are delicately poised between “upper heaven and the prole abyss”.

He agrees with Lord Melbourne, who said: “The higher and lower classes, there’s some good in them, but the middle classes are all affectation and conceit and pretence and concealment.”

As for “proles”, Fussell likes them. High-proles are skilled craftsmen, mid-proles are operators, like bus and truck drivers, low-proles are unskilled labourers. He quotes poignantly someone he would classify as “low-prole”, saying: “Most of us … have jobs that are too small for our spirit.” You see that every day and everywhere in South Africa.

Top out-of-sight

But what about the lumpenproletariat, the “bottom out-of-sight” in his description?

Well, says Fussel, they are very similar to the “top out-of-sight”. They don’t work for a living, and they are, at least in the US, hidden away. The top out-of-sight is literally out of sight, living in estates where you can’t see the house from the road. And the bottom out-of-sight, or the destitute, are hidden away in welfare or correctional institutions. Not so much in South Africa.

It’s a provocative and funny book, but it throws a light on the mechanical, functional and rather dumb simplicity of the Marxist dogma.

Where I might differ with De Ruyter is that the use of the term in ANC circles doesn’t necessarily suggest a party with an out-of-date philosophy, although you do get hints of that now and then. But the real problem is something worse: snobbery, or a kind of droit du seigneur.

This week, in response to a parliamentary question by the DA, Minister of Public Works Patricia de Lille revealed that South Africa’s 26 ministers and 32 deputy ministers stay in 97 mansions in South Africa. Average value of the house? R10-million. And they get free water and electricity.

They are so “top out-of-sight”. BM/DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Of ANC members, especially those in the NEC and in cabinet or top government positions can call each other Comrades- when they are busy with an ANC function or at Luthuli Hse.

That greeting however has no place when they are busy with a state or government function.

The SPD members in Germany also call each other Genosse at their meetings, but never would the SPD ministers in the coalition government dream of calling themselves Genosse outside of this.

Our ANC simply conflates itself with the state, because they see themselves entitled to it.

Well written and entertaining to read.

I don’t disagree with your analysis of the ANC, Tim, but you really need to brush up on your Marxism. Your understanding of Marx and Engel’s thinking is stuck in the Stalinist bastardization of the mid 20th-century. To the extent that Communists went along with the simplistic idea that ideology is directly determined by economics, they deserve blame. But Marx and Engels certainly didn’t hold the views you attribute to them. Critically, they understood the revolutions of 1848 to be primarily bourgeois revolutions, not working-class revolutions. Their enthusiasm for “workers of the world unite” at the time was based on the notion that if the bourgeoisie managed to become ascendant, the conditions would soon be right for the working class to pursue its own agenda. That obviously didn’t happen, and arguably still hasn’t.

It’s true that Marx tended to write scathingly about the lumpenproletariat, but it wasn’t because they didn’t see the world the way he wanted them to. He saw them in the same category as the rural peasantry, i.e., available for political manipulation by other class forces.

But as far as the ANC’s own misuse of the concept goes, you’re spot on.