ESCAPE

The Orange-Fish Tunnel: A truly great South African engineering feat

With its dark, subterranean passageways, it looks a little like an underground film set for one of those old James Bond movies. Opened in 1976 and built to last 300 years, the Orange-Fish Tunnel remains one of South Africa’s most outstanding engineering feats.

One of the Karoo’s more obscure tourism attractions lies 150 metres underground, smells faintly of fish and is open to the public for only a few weeks a year.

Here, under a distinctive flat-topped hill called Teebus Kop, between the small Eastern Cape towns of Steynsburg and Hofmeyr, is the outlet end of the world’s fourth-longest continuous aqueduct, the Orange-Fish Tunnel.

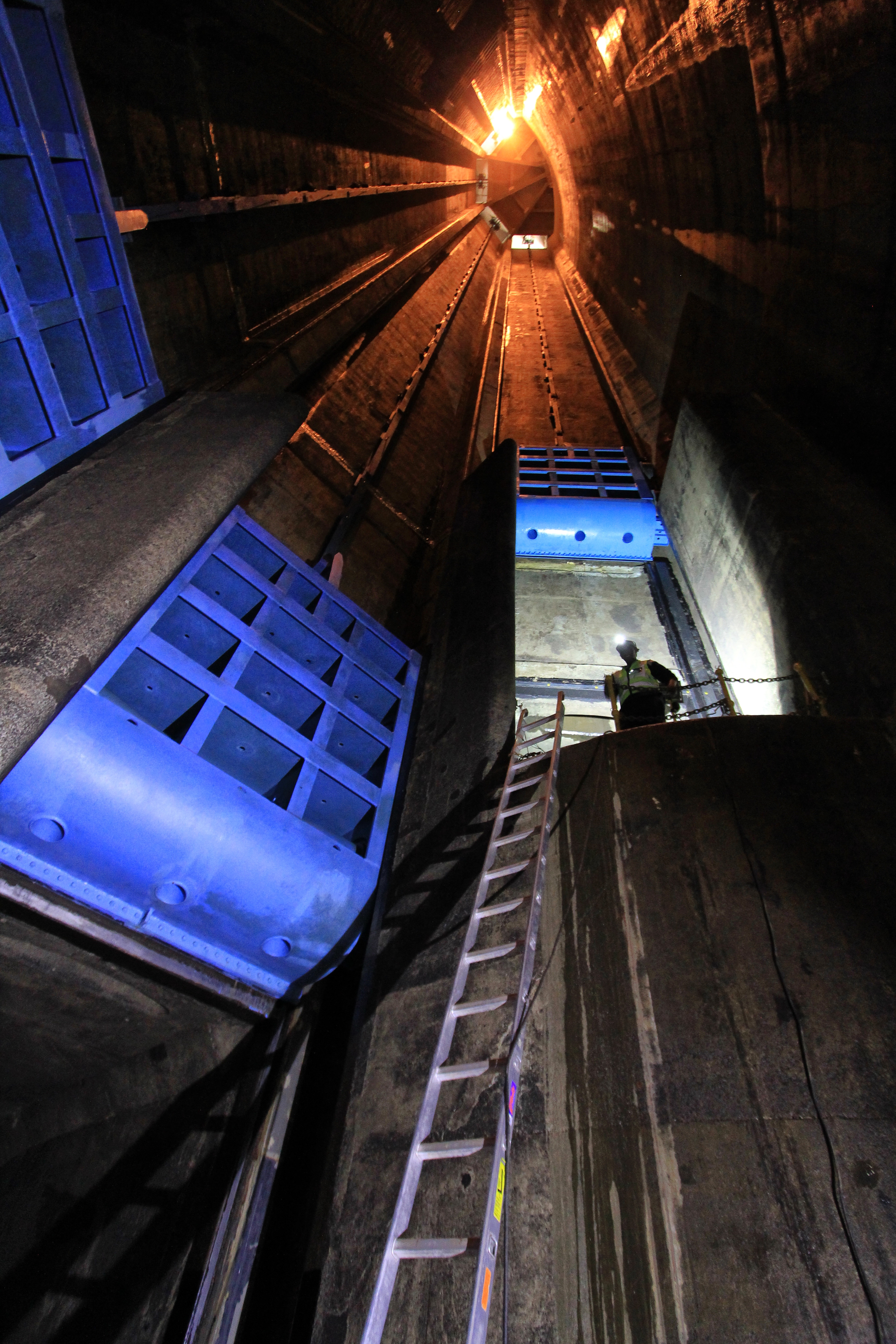

With its dark subterranean passageways and a large valve chamber hewn from solid ironstone, it looks a little like an underground film set for one of those old James Bond movies – the ones full of weird machinery and busy men trotting around in overalls, overseen by an evil man stroking a large kitty. Opened in 1976 and built to last 300 years, the Orange-Fish Tunnel remains one of South Africa’s most outstanding engineering feats, critical for millions of people in the Eastern Cape.

The road between Steynsburg and Middelburg in the Eastern Cape leads between Teebus (left) and Koffiebus. Image: Chris Marais

A horse, a pony and a couple of donkeys keep one another company with the distinctive hills of Teebus and Koffiebus in the background. The Orange-Fish Tunnel ends at Teebus. Image: Chris Marais

Teebus and Koffiebus (Tea and Coffee Canister) are two of the most distinctive hills in the Eastern Cape Karoo. Image: Chris Marais

Thanks to the Orange-Fish Tunnel, the Fish River valleys north and south of Cradock have become valuable irrigated land, where pecans, walnuts, lucerne and maize are successfully grown. Image: Chris Marais

There is also a canal linking the Fish River with the Sundays River, flowing through the citrus orchards near Addo and Kirkwood. Image: Chris Marais

The lifeline to the EC Midlands

For more than 11 months of the year, an average of 22 cubic metres of water per second from the Gariep Dam thunder through this 82.8km underwater aqueduct beneath the Suurberg Mountains, supplying the towns of Cradock, Cookhouse, Steynsburg, Somerset East, Bedford, Adelaide, and the cities of Makhanda and Gqeberha.

The water irrigates crops and dairies in the fertile Eastern Cape Karoo Midlands as well as the multi-million rand Sundays River citrus orchards around Addo and Kirkwood.

The Orange-Fish Tunnel becomes a fleeting tourism attraction in midwinter when the massive cloverleaf intake roller-valves at Gariep Dam are closed. The constant roar of the water subsides to a trickle while a maintenance team from the Department of Water and Sanitation comes in. Dressed in overalls, gumboots and head torches, they splash through this odd world, with the occasional fish or crab brushing past their ankles in the deeper tunnels as they caulk walls, fix holes and replace the worn linings of the pepper-pot valves specially designed to control the flow of the water.

Water streams into the tunnel from the giant intake tower for most of the year. But for a few weeks, the giant cloverleaf valves close off the flow (in midwinter) for tunnel maintenance. Image: Chris Marais

The Fish River Canoe Marathon boasts challenging rapids, weirs and chutes. Image: Chris Marais

Before 1976, the Fish River was a seasonal river, often just a string of green pools. But ever since the tunnel was completed, it has brought the region to life through irrigation agriculture and sports events like the annual Fish River Canoe Marathon. Image: Chris Marais

The Cradock Weir is a favourite spot for canoeists along the Fish River. Image: Chris Marais

Visitor access

During these few weeks, visitors (usually curious irrigation farmers and their friends) are allowed to see this exceptional place from the inside, as long as there is someone available to guide them around.

A small group of visitors, about the enter the dark, damp tunnels below. Image: Chris Marais

The ‘pepperpot valves’ are crucial for slowing down the thundering speed of the water at the tunnel outlet. Image: Chris Marais

In midwinter, Water Affairs closes the giant cloverleaf intake valves at Oviston to allow maintenance on the tunnel. Image: Chris Marais

Dressed in overalls, gumboots and head torches, the maintenance crew splash through this dark network of tunnels, with the occasional dead or live fish or crab brushing past their ankles in the deeper tunnels as they caulk tunnel linings, fix holes and replace valve linings. Image: Chris Marais

The Orange-Fish Tunnel remains one of the most ambitious and useful engineering marvels in South Africa. Image: Chris Marais

Planning for this part of the Orange River Project began in 1963 and included aerial photography, geological mapping and the drilling of nearly 300 exploratory boreholes. This underground aqueduct is so long that engineering calculations had to take the curvature of the Earth into account. Along the length of the tunnel, scientists from the Geological Survey of South Africa noted anomalies in the gravity field, so adjustments had to be made in surveying techniques to minimise “levelling errors”. Engineers used lasers – then a really cutting-edge technology – to keep the tunnel in line as the miners dug through solid rock. The calculations were so accurate that when the tunnelling teams later broke through and met one another, they were less than 4mm out of alignment.

Rockfalls and methane fires

Department of Water Affairs resident engineer WJR Alexander remarked at the time that this tunnel was “50 miles of risks and unknowns”. He was right. The work was dangerous and had to be remarkably precise. All the way, there were rockfalls of mudstone and sandstone, explosions and floods of groundwater, as they drilled through iron-hard dolerite. One methane-fuelled fire burnt for months and was so hot it melted the rocks.

No fewer than 102 people perished in the building of the tunnel. A commemorative document reads: “Some who died were from distant lands; the tunnel is their enduring monument.”

The construction project – too huge to entrust to one civil engineering contractor – was split into three. Entire work camps – essentially full towns – had to be created from scratch. At its peak, the building of the tunnel would involve a workforce of 5,000 locals and foreigners from around the world, including junior and senior engineers from Britain, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Belgium.

The world comes to the Karoo

Everything was of the highest standard, with no expense spared.

Official tunnel records note the townships were “almost entirely self-contained, with their own electric lighting, sewerage, roads, medical clinics, primary schools, administrative staff and artisans’ quarters, all recreational and sporting facilities (including swimming baths, all-weather floodlit tennis courts, football fields etc), staff housing, site offices, assembly halls, shopping centres, banks and other appropriate amenities”.

While a French-South African consortium called Union Corporation-Dumez-Borie was occupied with building the actual dam, another called Batignolles-Cogefar-African began on the 78-metre-high intake tower. This would divert a quarter of the dam’s water to the dry Eastern Cape Karoo’s fertile ground via the tunnel to the Teebus Spruit, Great Brak River, and, finally, the Great Fish.

The workers’ village constructed there became known as Oviston – a shortening of Oranje-Vis-Tonnel. A South African company called Orange River Contractors handled the middle plateau section (based at a work town called Midshaft), and an Italian-SA enterprise called JCI Di Penta took on the outlet at a town called Teebus, named after the nearby hill shaped like an old-fashioned tea caddy.

The ‘holing-through’ party

During construction (part of it deep underneath the house where President Paul Kruger was born in Bulhoek Valley), nearly 2.5 million cubic metres of rock were removed from the tunnel excavation. Picture two Empire State Buildings, and you’d have an idea of the volume.

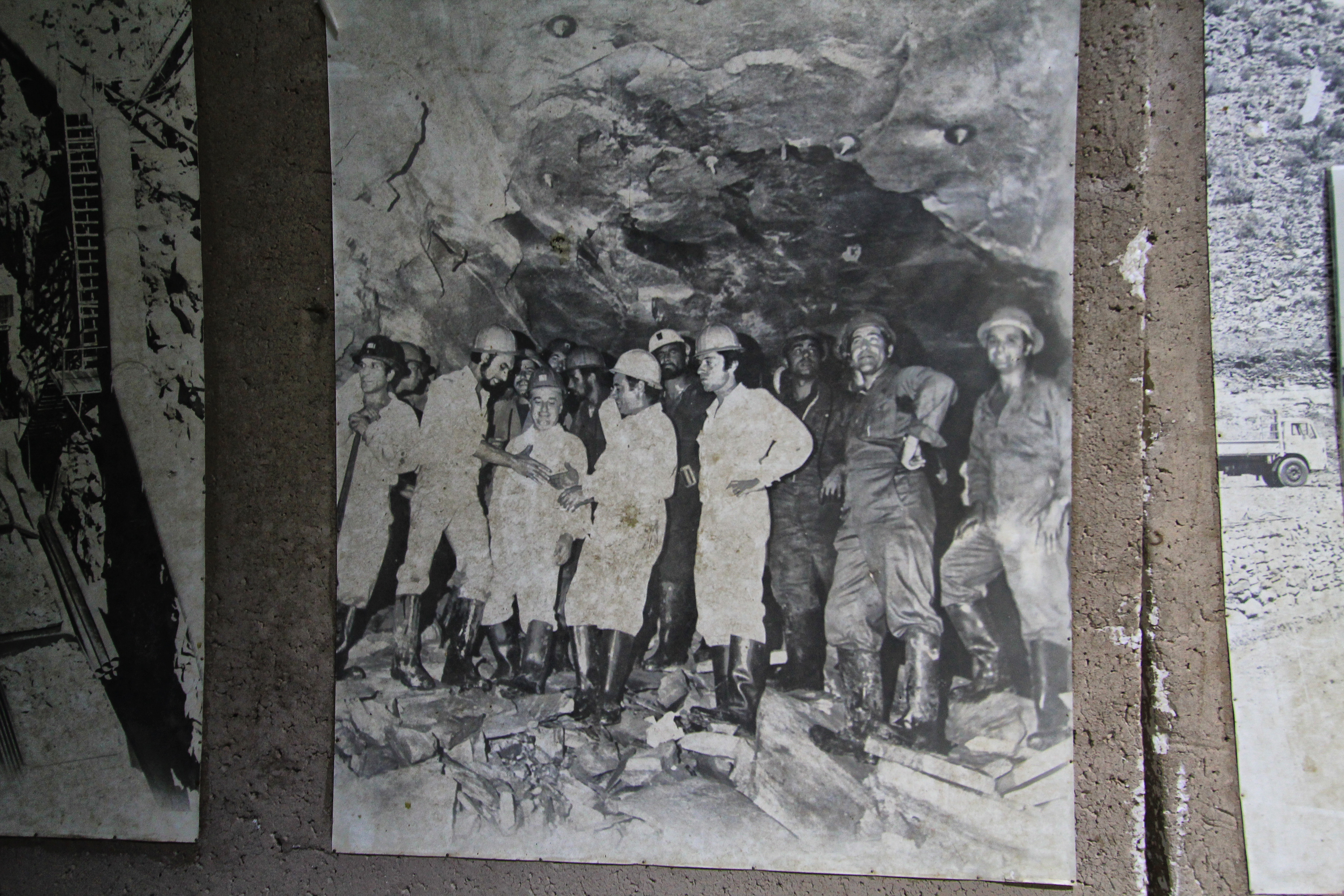

In January 1973, Water Affairs Minister SP Botha and departmental secretary JP Kriel hosted an olive-and-wine party 200 metres under the Karoo to celebrate the “holing-through” of the Plateau and Inlet sections. More from the booklet:

“Frenchmen, Italians and South Africans cheered lustily when the final blast was detonated by the Minister. The sudden inrush of chilly air was a welcome relief to the party of VIPs and newsmen who, only minutes before, had been sweltering in a typical blistering Karoo heatwave.”

Every week, 14,000 tons of bulk cement were brought in, first via 40-ton rail tankers to three small railway stations around the tunnel, and then trucked by road. By the time it was completed, the 5.33m-wide tunnels had been smoothly lined with 842,000 cubic metres of concrete with a minimum thickness of 230 millimetres. This job alone set records for its sheer unprecedented magnitude in South Africa. Dam history records that the building of new roads “opened up a part of South Africa never seen before by more than a bare handful of farmers on the Suurberg Plateau”.

One of the ‘holing through’ celebrations. Image: Chris Marais

The thrill of foreign newcomers

Locals still remember the thrill of all these exotic foreigners moving into their midst in the late 1960s. Suddenly there were movie houses, drive-ins, Olympic-sized swimming pools and social clubs springing up. There were musical evenings. At one stage, more Italian and French was heard around Venterstad and Steynsburg than English or Afrikaans.

Dave van Heerden, now living on Johannesburg’s West Rand, was a young boy when his father started work at Midshaft.

“I still remember the movie house and the shop, like a mini-Makro. There were 150 kids at school with me, all between Grade 1 and Standard 5. The weather was extreme. I’ve still got a slide picture my dad took of me in the snow – on 16 December 1970!

“It also made a big impression on me when they brought in this enormous tunnelling machine from France that cost many millions of rands. It used to move forward on funny little peg legs. I’m pretty sure they ended up leaving it underground in a tunnel somewhere.”

A specially-designed vehicle was built to inspect the tunnel. It had a diesel engine, completely sealed electrics and a cab at each end so it could be easily driven forward or back. A bicycle was attached in case the vehicle had a problem, allowing the driver to ride back through the tunnel. As with the tunnelling machine, no one knows what has become of it.

Like catching fish in a tunnel

The first water from the Gariep flowed through in 1976. Farmer Charles Jordaan still remembers the day the tunnel was opened. Everyone stood waiting to see the water. When it arrived, tons of dammed-up fish also came through.

“We caught them in netting and hauled them away by the bakkie-load. Everyone feasted on carp and barbel.”

Stephen Mullineux, now retired from the Department of Water Affairs, stands on the old diving board at abandoned Teebus. Image: Chris Marais

Teebus, which once bustled with Italian and South African tunnel-workers, is now abandoned, a ghost town. Image: Chris Marais

The old pump house at the Teebus. Image: Chris Marais

The town of Oviston lives on as a quiet place of holidaymakers and retirees who have modified the old engineering camp’s prefab houses, most of which have great views of the Gariep Dam. But the engineering villages of Teebus and Midshaft have long been abandoned and fallen into ruin. At Teebus, where Italian tunnellers worked and lived with their families, guarri bushes are slowly taking over the brick and stonework of the recreation centre.

The massive space of the swimming pool is still there, presided over by a tall diving board. Some of the pines, poplars and beefwood trees have survived.

A rusted sign admonishes passing lizards and red-winged starlings that swemdrag moet ordentlik wees (swimwear must be decent) and that revellers should not toss their beer bottles into the swimming pool. You don’t have to read between the lines to realise that the Tunnellers of Teebus worked hard – and possibly partied even harder. DM/ML

This is an extract from Karoo Roads II – More Tales from the Heartland, by Chris Marais and Julienne du Toit.

For an insider’s view on life in the Dry Country, get the three-book special of Karoo Roads I, Karoo Roads II and Karoo Roads III (illustrated in black and white) for only R800, including courier costs in South Africa. For more details, contact Julie at [email protected]

Stunning images. I take it the engineers involved didn’t work in Ellisras as well?

Amazing! Wonderful read

This was great, thank you! In a world where the looters are looting with impunity, it feels good to be reminded of who John Galt is.

Wow amazing read. They were such insightful people to have thought this all through in order to have better use of the land and bring water to the Eastern Cape.

What a ray of sunlight – fascinating and inspiring Julie thank you!

So interesting to read, accompanied by excellent photographs – thank you. Growing up with a structural engineer as a father, married to a once-was-civil engineer and having had, back in the 80s, the privilege of working for a top SA firm of engineering consultants, I really appreciate reading a story which highlights one of South Africa’s many extraordinary engineering projects.

What did they do with the “nearly 2.5 million cubic metres of rock”?

And, by the way, that part of the tunnel’s water that was reserved for Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha) just needed a short pipeline and some internal plumbing to get there.

So the city’s current water problems are not really about drought, just the result of a 10+ year delay before they started doing the right thing….

Mike, as you well know, the fact that politicians have over two decades not listened to recommendations by professional engineers about the necessity to build strategic infrastructure is a significant reason contributing to the problems we now face.

Malcolm

I believe the pipeline from the Gariep to PE has been operating for maany years, delivering 250 million litres per day. Hence there will never be a true Day Zero in PE. The problem they do have is that not all parts of the city are connected to the pipeline.

This is an impressive and welcome article describing one of our major engineering achievements in SA. I see from the notes at the end of the article that you are concentrating on water projects only and many of these involve long tunnels. As a retired professional civil engineer with 65 years practice in the profession, and a previous chairman of the SA National committee on tunnelling I would hope that you would expand your writing to rail and road tunnels as well. South African engineers hold a good reputation internationally. It is a pity that one of the reasons for the problems in the country is the fact that the ANC politicians ignored the potential of engineers in our country.

A great engineering/mining feat. Today such feats of excellence are impossible to replicate thanks to the corrupt cadres of the ANC

It is a crying shame that the hydro electric generators at Teebus (exit) have been damaged and not repaired. Gross neglect. We could do with the power they would have generated.

A wonderful piece on a fantastic achievement. A tribute to what can be achieved where meritocracy rules.

For all their faults (and there were plenty) the old NP government delivered on infrastructure. Of course there was corruption and backhanders, there always is in government. Pity our current infrastructure builds do not show the same level of accomplishment, probably as the percentage of palm-greasing has gone from 10% to 80%

Stunning, really enjoying this new feature of DM; articles to make us proud of being South African again. Once we truly were a great nation.

I wonder how well it is being maintained now – and how much longer it will last?

Marvellous. My father worked on this project as a surveyor for Waterwese, up in the Highveld we grew up with momentous names like Koffiebus and Teebus. We visited him one holiday in a brandspanking new town built alongside PK le Roux Dam (Vanderkloof, today).

Jip and since then we achieved nearly nothing or can we get a list ?

An amazing feat of engineering at that time. The Nationalist government can be really proud of a lot of its accomplishments in building South Africa into the powerhouse it used to be. This article is a wonderful look back through the window of time to enormous achievements and perhaps a simpler way of life.

Flying from OR Tambo to George, one passes over the west side of the Gariep dam. I have always wondered what the penstock protruding out of the dam near Oviston was for, and now I know!

How many South Africans know just what a great country we live in and take time off to visit such places of interest and all the other amazing things and people of this wonderful country?