ESCAPE

Gariep: The story of South Africa’s largest dam

The Gariep Dam has been well over 100% full for several months now, with more water on its way. Here’s the story of this remarkable dam, right in the middle of the country.

We’ve seen it in the rushing spectacle of the 2011 floods, the bone-crack drought of 2016 through 2019, through fawn winters and late-summer rainstorms. It’s different every time.

At first light, the surface is dark blue and copper. By midday, it is a moody khaki colour. In the late afternoon, it’s shot silk, silvery pink and pale blue. At night, the moon casts a bright path across the pewter-smooth water, and the clouds merge with the hillocky flat-topped islands as the dark sky falls to earth. In the summer, lightning flickers in the towering thunderheads before they drop magicians’ cloaks of invisibility, hiding the horizons and then the islands with wet veils before lifting them to reveal a dramatically shiny landscape.

Water tourism

One of the best places to behold this rather extraordinary body of water – South Africa’s Mother Dam – is from a balcony at De Stijl Gariep Hotel on the hilltop overlooking the landscape.

But when it is overflowing, people head straight for a view of the spillway, where the wall rises smoothly like a man-made cliff and the water tumbles over like a neat Victoria Falls. This only happens when the dam level tops 100%.

Every time the Gariep Dam reaches capacity, the water tourists stream into the area. Flood time is boom time, as they’ll tell you around Gariep.

When the dam overflows, the spillway looks spectacular, attracting ‘water tourists’ from all over the country. Image: Chris Marais

Splendid skies above the Gariep Dam, which sprawls over 370 square kilometres. Image: Chris Marais

Hills poke through the water, making islands where once there was a sprawling Karoo veld. Image: Chris Marais

Rain clouds approaching South Africa’s largest dam. Image: Chris Marais

Cruising the dam

Wikus Wiese has a flat-bottomed craft equipped with tables and chairs leaving most afternoons from the jetty at Forever Resorts.

He has lived in the town, on and off, for most of his life, as has his assistant pilot, Jacques Ackerman. Wikus efficiently guides the boat through the yacht basin where the various vessels gleam in the lowering sun, with names like Vlugvoet, Star Spirit, Just for Fun, C’est la Vie, Felicity, Firefly and Wild Child. A profoundly inelegant and nameless flat-bottomed raft is also moored there “just for braais”.

In December’s peak holiday season, when all 63 guesthouses in Gariep are full to capacity, he does this trip up to seven times a day.

At a respectful distance away from the dam wall, Wikus stops the boat. From this vantage point we can see the faint brown highwater mark right across the dam wall, more than a metre above the water. This marks the time of sustained floods in 2011, when the Caledon and Orange rivers rose dramatically and practically simultaneously, filling the Gariep Dam way faster than it could empty.

The yacht basin at the Gariep dam, is accessible via the Forever Resort. Image: Chris Marais

The upmarket De Stijl Gariep Hotel offers some of the best dam views. Image: Chris Marais

The distinctive red roofs of the Gariep Forever Resort. Image: Chris Marais

Water vapour rising to meet the clouds from the overflowing spillway – far right. Image: Chris Marais

Setting off on an afternoon boat cruise across the dam. Image: Chris Marais

Where big sky meets big water. Image: Chris Marais

Dam builder towns

Our guide tells us how the Gariep remained over 120% full for three whole months, water roaring over the spillway at a rate of five Olympic swimming pools per second. The only time the dam topped that level was very briefly, in 1988, at 129%. Barely five years later, officials recorded the dam’s lowest level at 19%.

Wikus also explains why the towns originally established to accommodate dam builders in the 1960s have remained comparatively small. They include Gariep (population 2,000, rising to 10,000 in the holiday season) and Oviston (population well under a thousand). Despite the splendid water views, neither town sports flashy casinos or timeshare accommodation. There is no Karoo Riviera to be found here.

“The water that is stored here is extremely important. It is the lifeblood of the Eastern Cape right down to Gqeberha, and also the Free State. Millions of lives and jobs depend on it, so it must be kept as clean and unpolluted as possible.

“That and possible floods is why the whole dam, practically, is surrounded by provincial nature reserves along the 430km shoreline. We often see ribbokke on the islands, buffalo, eland, pairs of fish eagles.”

Read in Daily Maverick: Norval’s Pont in the Northern Cape — where legends shine forever

Too cold for crocs

Unlike Kariba, Africa’s largest dam, there are no hippos and crocodiles.

“It is way too cold for them,” says Wikus. Despite being situated in the mid-Karoo, the Gariep’s water temperatures seldom rise much above 9 deg C in winter, and 12 deg C in summer. This is mostly because the dam’s water comes from the icy Lesotho Highlands.

Wikus carries all the facts and stats in his head. Surface area of the dam? Close to 40,000 hectares when full. Circumference? 435 km. Hydropower into the grid? Four spinning turbines generate 90 Megawatts each, together enough to power 70,000 households when they are running. And then suddenly we were floating over the invisible line dividing the Eastern Cape from the Free State. Somewhere below us was the ravine where Dutch explorer and soldier Colonel Robert J Gordon became the first European to see the river. He named it in honour of the Dutch Royal Family back in 1777.

According to the Water Research Commission’s Water Wheel editor, Lani van Vuuren, the Orange River Project (building and linking the Gariep Dam and the Orange-Fish Tunnel) happened in part because of the international shockwaves caused by the Apartheid government’s shooting of 69 Pass Law protesters at Sharpeville in 1960. The government of the day “needed to restore confidence in the country’s economy”.

Mega projects

It wasn’t a new idea, though. Back in 1912, Dr Alfred Lewis, who was to become Director of Irrigation, went on a gruelling trip down the Orange River in 41°C heat and later wrote a detailed report about the potential of diverting part of the river’s water through a series of tunnels to the Great Fish and Sundays Rivers.

He and many others recognised how it would unlock the potential of the drought-plagued Eastern Cape Karoo, where the soils were fertile but the rainfall sparse and the rivers ephemeral. The Orange River Project (ORP) was proposed to the government in 1948 but it was dismissed as too expensive. In the end, it was international pressure and the threatened outflow of foreign capital in 1960 that provided the trigger, and R490-million was collected to fund the project – about R75-billion in today’s money, estimated one water engineer.

When the decision was made to embark on the Orange River Project in the early 1960s, the South African government called for tenders from contractors all over the world. The main one was awarded to a French-South African consortium called Union Corporation-Dumez-Borie Dams. Thousands of workers poured in from faraway countries.

The dam, where three provinces meet (Eastern Cape, Northern Cape and Free State), is surrounded by a series of nature reserves. Image: Chris Marais

From 1912 onwards, several have seen the potential of a dam in this area, but it was only tackled in the 1960s. Image: Chris Marais

The channels formed by the Orange River as it flows into the dam near Bethulie. Image: Chris Marais

The Hennie Steyn rail-and-road bridge outside Bethulie, which arches over the Orange River before its banks broaden into the massive Gariep Dam. Image: Chris Marais

Multilingual bars

Paul Johns, a German of Welsh descent, left Europe after the Second World War to work in South African mines and then Kariba, before taking a job at Gariep. Paul was part of the team that tunnelled underneath the river to check the geology and he later worked on cementation.

“I remember hearing seven different languages in the bar some nights.”

Construction on the new dam, the largest in the country, began in 1965 and was completed in 1971. Initially called the Ruigte Valley Dam, it was later named after Hendrik Verwoerd and then renamed the Gariep Dam in 1996, using the original Khoi name for the river. Work on its graceful double convex arch began in 1966. The wall is 88m high and 914m long. Built using a staggering 1.92 million cubic metres of concrete, it rests atop a thick geological slab of ironstone. The egg-shaped curvature of the wall spreads the tremendous pressure of the water towards the rocky abutments.

Inside the wall

The national Department of Water and Sanitation has offices overlooking the dam and occasionally takes groups on tours into the wall. Remarkably, it is not completely solid, and has 13km of passages and staircases leading right to the bottom.

Every day, someone from the department goes down into the wall to record the slight movement of the concrete. This is a job for one who is fit and undaunted by stairs. The dam wall is about 28 storeys high, and there is no elevator.

When we were there, that person was Joseph Alexander, who kept up a steady pace down hundreds of steps and all the way back up again. We paused at the enormous turbine hall, which has occasionally been hired out for dances and launches, with a cash bar in the corner. In 1998, local farmers staged a sheep auction here, although no one seems to remember whether the woolly beasts in question were actually present.

Following a guide deep into the dam wall. Every day, someone goes down to measure how much the dam is flexing. Image: Chris Marais

The dark ‘teeth’ poking out under the spillway are the Roberts Splitters; there to dissipate the force of falling water. Image: Chris Marais

The Roberts Splitters

We paused again at the spillway, the water coming down in a neat, fine sheet.

At the top of it, hardly noticeable, were the Roberts Splitters. These are deceptively simple but carefully engineered dark “teeth” projecting over the crest of the dam wall. They help dissipate the kinetic energy of the overspill water, making it tumble back and forth instead of falling in a steady scouring sheet that could eventually erode the rock at the foot of the wall – a major problem plaguing Kariba.

The splitters were named after a South African engineer, Lieutenant-Colonel DF Roberts, who came up with the design in 1936, long before this dam was built. They’ve been used on 23 dams in South Africa, including Gariep, Vaal, Loskop and Vanderkloof, and have been deployed around the world. And we stopped again when we reached the rock bottom of the dam wall. Only metres apart, in a dank place far below the surface of dam and earth, Joseph stood on the Free State side, and we stood in the Eastern Cape.

The Long Bridge at Bethulie

It’s fairly well-lit but so cave-like that the steady drip of condensed water has created small calcite-rich colonies of stalactites and stalagmites. Halfway up again, we panted while taking in the massive hydraulic actuators that are tested every few months. They power the pistons that open and close six massive sluice gates weighing 95 tons each.

When visiting Gariep, you should also do the very pleasant drive to Bethulie, close to where the dam starts, and stand atop the Hennie Steyn Bridge. With its pleasing arches, this is the longest road-and-railway bridge in the country. It stands tall and proud over the Orange River far below.

One of the final stages originally envisaged by the Orange River Project was the possible heightening of the dam wall if silt build-up began to limit its capacity, which is why this bridge is so lofty.

It has not escaped the attention of Bethulie residents that if the dam wall is ever added to, all that would remain of the town would be their moederkerk church steeple, poking above the water. And, of course, this graceful bridge. DM/ML

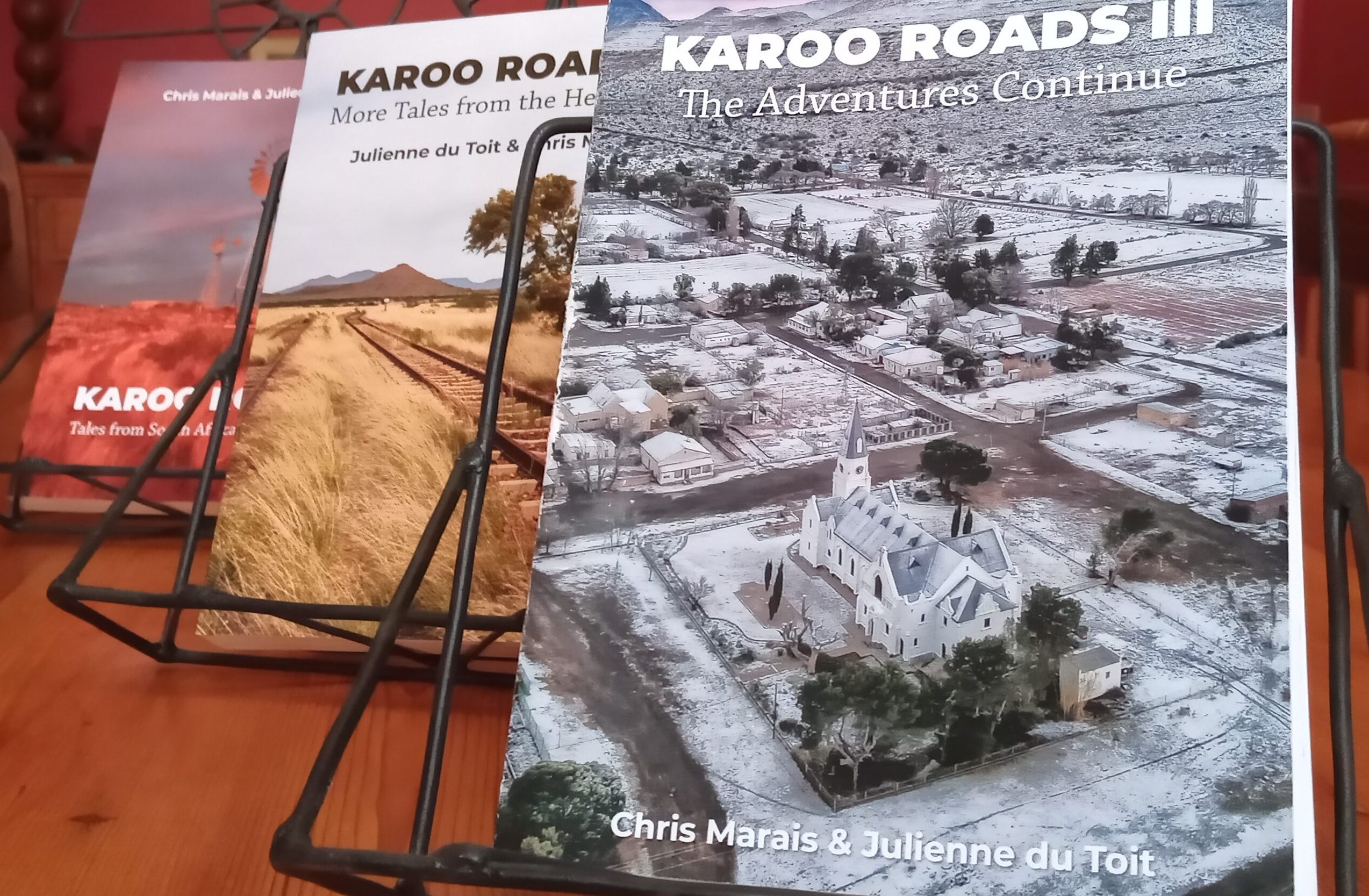

This is an extract from Karoo Roads I – Tales from South Africa’s Heartland, by Chris Marais and Julienne du Toit.

For an insider’s view on life in the Dry Country, get the three-book special of Karoo Roads I, Karoo Roads II and Karoo Roads III (illustrated in black and white) for only R800, including courier costs in South Africa. For more details, contact Julie at [email protected]

‘Karoo Roads’ Collection. Image: Chris Marais

An incredible sight,but why oh why is the hydro electric station silent????

Now I really want to go there. Thanks.

My only visit and overnight stay was in 1976.

Oh what a fascinating story! Looking at the bright side of things sometimes, during lockdown one of the joys we restored as a family was driving instead of flying to CT from Joburg. On our way back from CT we spent the night at one of the guest lodges where we were greeted by these spectacular views from our balcony. Our love for road trips was rekindled. From lockdowns to load shedding, our country is beautiful nonetheless.

In 1974, as a student engineer at Wits, I went down the tunnels right to the bottom of the wall, where we stood on the bedrock almost under the concrete wall. We also climbed through the scroll casings of the turbines which were still under construction at the time.

I have recently bought the three Karoo Roads books. Really fascinating and well written. Even better to see the pictures in colour in articles like this.

I visited the dam in 1969 when it was still being built and i remember that visit as if it were yesterday. a masterpiece of engineering that the government has not been able to mess up. YET?? And the time taken to build it is impressive.. What can be done when there is proper engineering / design and a will to make it happen. Shame we don’t seem to have this vision from our government anymore. Phase 2 of the Lesotho Highlands water project springs to mind. Many years behind schedule with the money mostly used to feed those at the trough.

Excellent article. I lived as a child from January 1965 to January 1968 in ‘Oranjekrag’. Our primary school had three sections: Afrikaans, English and French. A privilege to observe the birth of this project!