ESCAPE

Norval’s Pont in the Northern Cape — where legends shine forever

From the bar to the blockhouse, Norval’s Pont is all about its backstory.

In the summer of 2009, I came to Norval’s Pont to see the longest bar counter in the Northern Cape. Within the space of five minutes and one double Jameson, I was more interested in David Kramer’s electric guitar and the smoking crocodile under the old dial-up telephone than anything else.

I also liked the bumper stickers around the Glasgow Pont Hotel. The first one read: “Where the $#%# is Norval’s Pont?”

The second: “Norval’s Pont: Not as Kak as You Think”.

I made myself dizzy — and a little sad — walking around the pub, reading the signs, looking at the old pictures of the Gariep Dam (then called Hendrik Verwoerd Dam) and the tintypes of the concentration camps where so many Boer women and children died.

Even the Going Nowhere Slowly TV crew had clearly been here and left their party graffiti: “Don’t fall off the wagon. Fall off the Pont.” — Viv Vermaak.

“All three-headed policemen are invisible.” — Ian Roberts.

Going Nowhere Slowly once had a bit of a cult following as it covered the rambling progress of a band of off-beat travellers roaming South Africa in a 1966 Chevrolet Impala that went by the name of Chilli Pepper.

Was this David Kramer’s old guitar?

Hotel owner Rod McGregor Mann arrived: shoulder-length grey hair, piercing eyes and lots of confidence; about the blue Gallo electric guitar behind the counter, he says: “I found it in Edenburg on a farm, in its case but covered with crap. This is actually David Kramer’s old guitar, last used when he played during his Budgie and the Jets era in 1982.”

McGregor Mann said he got hold of Kramer, who couldn’t believe he had found it. How much did he want for it? Nothing, replied McGregor Mann. Just come and get it and play a few songs. I finished my lunch, swigged back my drink and left — that’s the last I saw of Rod McGregor Mann and the Glasgow Pont Hotel. I often wonder if Kramer ever made it out here. I sometimes also think about that smoking crocodile. But when it comes to Norval’s Pont, I mostly think about an enterprising Scot and his two brothers who came to these frontier lands to make combs and hats.

Rod McGregor Mann and the David Kramer guitar he rescued from a farm. Image: Chris Marais

The enterprising Norvals

Fresh out of Glasgow in 1848, James Norval bought a farm called Dapperfontein on the south banks of the Orange River from one Petrus Brits and, instead of embarking exclusively on the normal agricultural practices of the district, went out looking for tortoise shells in the veld.

Somehow he and his kin had discovered that this part of the Karoo was well populated by the leopard and the berg varieties of tortoise — back then, combs were fashioned from tortoiseshell.

Having cornered the local market for combs and wide-brimmed hats, the Norvals did not stoep-sit and dream for long. They soon became part of the mega-sweep of southern African history as the interior of the country lit up with discoveries of gold and diamonds.

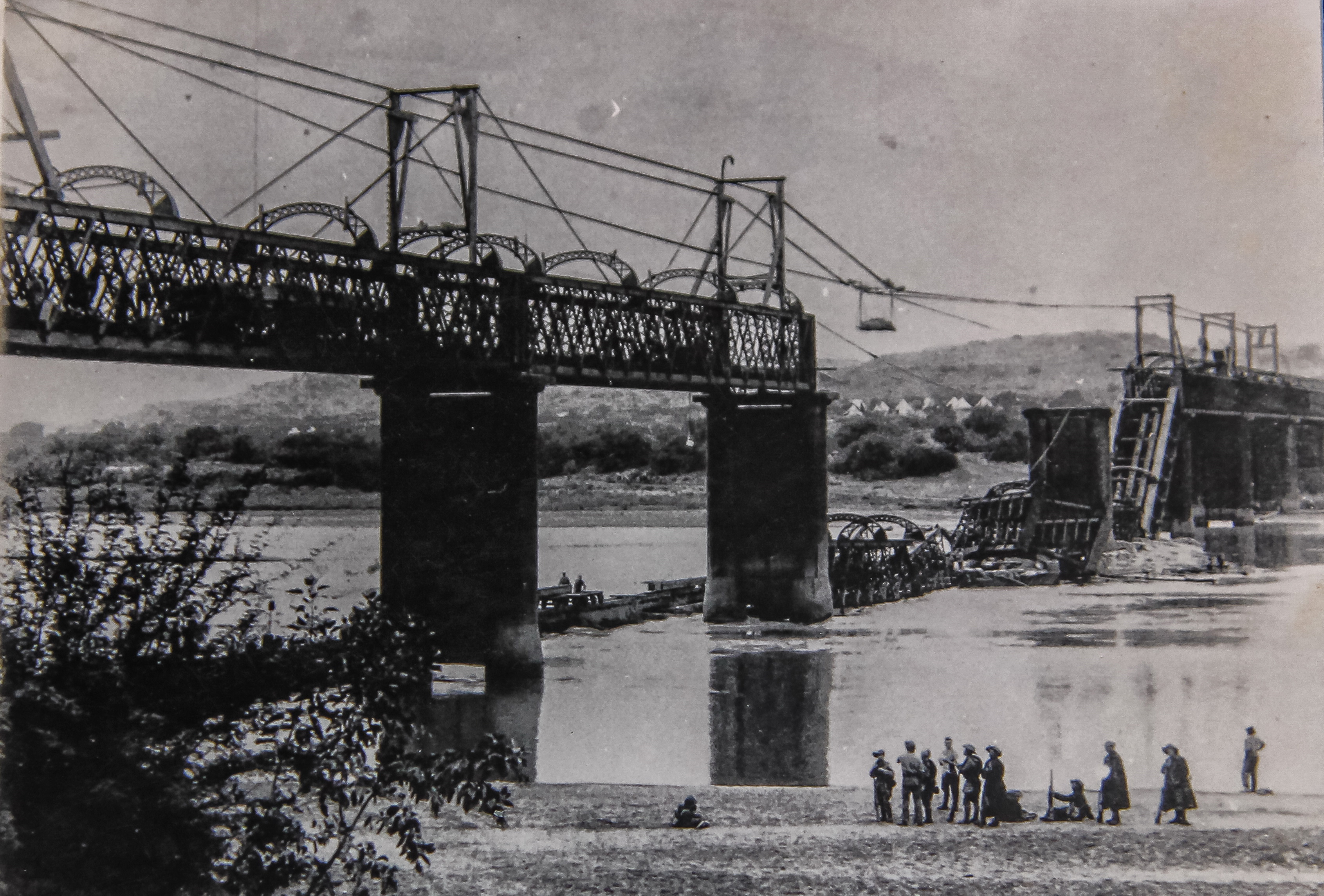

British military crossing into the Free State at Norval’s Pont. Image: Supplied / Chris Marais

Nearby Lake Gariep in the rainy season. Image: Chris Marais

Everyone, it seems, from prospectors to soldiers to salesmen and many more souls, wanted to cross the mighty Orange in their wagons and head north. Apparently, the idea of a pont across the Orange came to the Norvals via the British Army commander Harry Smith, who moved his troops across in inflatable rubber boats at the height of flood season.

Once the military crossing had been made, James Norval acquired the inflatables and went into business ferrying travellers across the river. Shortly after the rubber perished in the Karoo sun, a permanent wood and cable crossing was built and the spot became known as Norval’s Pont. For one pound, everyone, wagon and oxen included, was safely ferried over into the Orange Free State.

In the meantime, the Norvals had also set up a bar with some overnight rooms and, in honour of their roots and new money-spinning line of work, named it the Glasgow Pont Hotel. A hardy little sheep farm had now been transformed into a thriving village that hummed with north-south-north traffic, mainly drawn by beasts of some description.

The kit-form British bridge

Then along came the railways, and by 1890 a bridge spanned the Orange and steam locomotives were chugging across it. The 500m-long marvel of steel and concrete arrived in kit form from “the workshop of the world”, England, and was assembled on site.

Ten years later, retreating Boer forces paid this massive bridge little respect when they dynamited it. In no time, however, British sappers set up a pontoon bridge at Norval’s Pont and carried on operations. Long after the end of hostilities in 1904, a sturdy railway bridge was built at this spot across the Orange.

After my bar lunch and the Jameson that accompanied it, I found myself at Norval’s Pont Concentration Camp Cemetery in that late-afternoon light that brings on a wave of sadness in baboons and those who drink whiskey too early in the day; experts call it Hesperian Melancholia.

Engaging with the past — the Norval’s Pont concentration camp cemetery. Image: Chris Marais

Norval’s Pont Bridge after being blown up by Boers during the South African War. Image: Supplied / Chris Marais

By 1890 a bridge spanned the Orange and steam locomotives were chugging across it. Image: Chris Marais

Norval’s Pont Concentration Camp

The sign itself was enough. Even though Boer rights campaigner Emily Hobhouse classed Norval’s Pont as having “the best woman-camp” of them all, complete with school for 500, fountain-fed water source and an initial abundance of fresh vegetables, conditions soon became dire as the camp filled and supplies dwindled.

In the case of the South African War, the concentration camps were established to cut Boer guerilla fighters’ supply lines by removing their women and children from their farms — which they mostly then burnt to the ground. It was part of Lord Kitchener’s plan to end the ebb and flow of battle in the South African hinterland. The Brits held the major cities, but the platteland was another story.

Another segment of the Kitchener Plan was to establish nearly 8,000 blockhouse fortifications running right across South Africa and along the major rail routes. These would be manned and the spaces between them patrolled.

Military life in a blockhouse

The standard Orange River blockhouses were three storeys high, of dressed stone and low-pitch corrugated iron roofs. Steel firing boxes jutted out from the sides, water was stored on the ground floor which was separated from the first-floor sleeping quarters by a thick steel trapdoor, and the top floor was where you kept watch and shot from. Many blockhouse firing loopholes were numbered so that as a British soldier, presumably, you were assigned to a specific position. You were watered and fed by passing trains or, if stationed out in a veld blockhouse, via water carts and supply wagons.

Barbed wire, especially the much-prized eight-strand variety, was spanned between blockhouses right across South Africa. Spare a thought for the blokes in the blockhouse, some fresh from an English village, others from a faraway rural kraal, now in the middle of a very dry nowhere, living the typical army dream of “hurry up and wait”.

Someone in the bar on that day in 2009 told me there was still a blockhouse left standing here at Norval’s Pont, but after my brief visit to the concentration camp cemetery I had simply run out of steam.

Civilian life in a blockhouse

In the midsummer of 2019, we follow up on the Norval’s Pont blockhouse lead — and it’s not a minute too soon. We’re about to meet the only living people to have taken an old South African War blockhouse and converted it into comfortable living quarters for themselves. The ultimate military treehouse, if you will.

The blockhouse at Norval’s Pont — home to Paul and Suzette Jones for 45 years. Image: Chris Marais

The guy who had owned the Glasgow Pont Hotel just before Rod McGregor Mann was Paul Johns. While living and working at the hotel, Johns decided to expand into vegetable and fruit farming. He and his wife, Suzette, bought an irrigation farm on the Orange River. He adored the place, the wild vegetation, the rush of the river, the toot of the trains crossing the bridge.

On the land he’d bought was an old British blockhouse, a sturdy fort made of stone and steel. Its twin had once stood on the other side of the river. Both had shooting slits and housed soldiers who guarded the bridge against the Boers. Not well enough, as it turned out. The twin fort on the other side of the river was dismantled by a farmer decades ago, its stones used to build a piggery

From a fort to a dwelling

Suzette’s father (she was from Venterstad) encouraged Johns to fix up the old blockhouse, then falling apart. He did more than that: he saw it commanded a glorious view of the river and decided it would be a splendid place to live.

And so the sturdy old blockhouse was to be transformed into a modern home. His first job was to clear out the snakes and rats, then make a doorway at the bottom. The British soldiers had used a ladder that led to a narrow entrance several metres up.

Turning a mini-fort into a modern-day dwelling was a work of love, construction genius and very crafty interior plumbing. The kitchen and living areas were at the bottom, with a fireplace that heated up the three storeys above it. He and Suzette thrived there for 45 years and raised four children in it. It was as snug and colourful as a Gipsy caravan. But for Paul Johns, the best thing was the view over the river, which he adored.

A blockhouse refitted for modern dwelling needs — creative and comfortable. Image: Chris Marais

Home, sweet home — in a blockhouse. Image: Chris Marais

Paul and Suzette Johns’ nearly-palatial bedroom on the top floor of their blockhouse. Image: Chris Marais

It was your typical Huckleberry Finn or Wind in the Willows kind of life for the Johns. The kids swam in the river and caught barbel (catfish) and often slept outdoors. They moved into a regular house nearby only when Suzette had a hip replacement and could not climb the blockhouse steps for a while. But now it was time to go.

“One of our sons has been nagging us to come and live with him on his farm outside Bloemfontein,” says Johns. “We’ve decided to move there now because I am over 80 years old and tired of farming. But I told him we would have gone sooner if he could divert the river there. I’ve loved so much about living here, the blockhouse, the farming, the veld. But it’s the Orange River that I’ll really miss.”

And just like that, another light goes out at Norval’s Pont. But the legends will shine on forever. DM/ML

This is an extract from Karoo Roads I – Tales from the Heartland, by Julienne du Toit and Chris Marais.

‘Karoo Roads’ Collection. Image: Chris Marais

For an insider’s view on life in the Dry Country, get the three-book special of Karoo Roads I, Karoo Roads II and Karoo Roads III for only R800, including courier costs in South Africa. For more details, contact Julie at [email protected]

In case you missed it, also read Saddling up and riding out with the cowgirls in the Karoo mountains

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I still have vivid memories of crossing the steel railway bridge at Norvals Pont, usually in the evening as I was heading homeward (to Margate on the south coast of Natal) from boarding school in Graaff Reinet. Those two day train trips are memories I shall cherish to the day I die.