SPACED OUT

The sensational Martian canals — life on the Red Planet as perceived by Percival Lowell

The discovery of life on Mars could truly be said to have depended on the eye of the beholder.

At some point, the acute drying of their planet became evident to the inhabitants of Mars. In a desperate attempt to maintain their civilisation, they initiated a vast project to canalise the annual snowmelt from the polar caps through a lacework of canals and oases across the planet.

The result of their final struggle against extinction from global warming was documented by the astronomer Percival Lowell in 1895 from his private observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, built specifically to study the Red Planet.

He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and his work would lead to the discovery of Pluto 14 years after his death. Claiming the possibility of Martian life created a public sensation and a good deal of scientific scepticism.

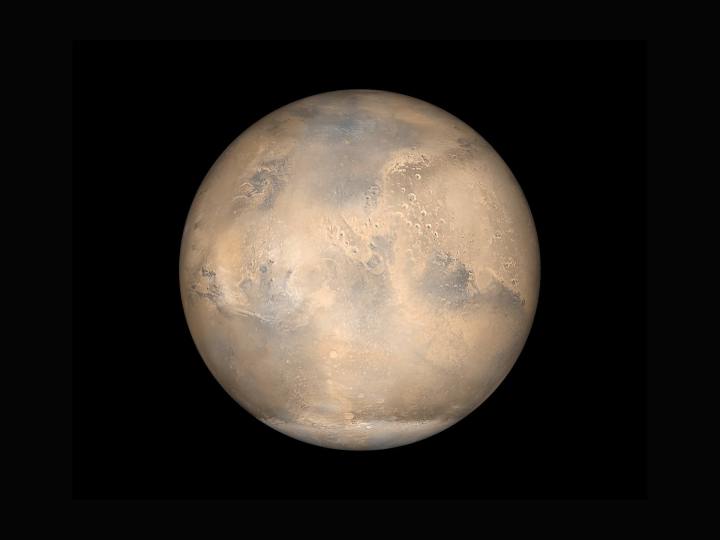

NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope snapped this portrait of Mars within minutes of the planet’s closest approach to Earth in nearly 60,000 years. This image was made from a series of exposures taken between 5:35 a.m. and 6:20 a.m. EDT Aug. 27 with Hubble’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2. In this picture, the red planet is 34,647,420 miles (55,757,930 km) from Earth. This sharp, natural-color view of Mars reveals several prominent Martian features, including the largest volcano in the solar system, Olympus Mons; a system of canyons called Valles Marineris; an immense dark marking called Solis Lacus; and the southern polar ice cap. Image: NASA/ESA, J. Bell (Cornell U.) and M. Wolff (SSI)

Lowell’s interest was sparked by the work of the 19th-century Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, whose observations of Mars included “deep trenches meandering across the red planet’s surface”. Schiaparelli used the Italian word “canali”, meaning trench, but Lowell translated it as canals and proceeded to confirm their existence and map the planet.

He wrote several books on the subject, the most famous being Mars and its Canals (1906), followed by Mars as the Abode of Life, and expounded his findings on many lecture tours. His books were illustrated with his maps and drawings of Mars, which were reproduced in numerous works by other authors in subsequent decades. It fed into the Victorian middle classes’ mania for maps and exotic fields of personal and national expression. The remoteness of Mars made it all the more exciting.

Read in Daily Maverick: ‘Red Seas’ of Mars: discovery of multiple ‘salt lakes’ shifts frontiers of planetary science

Lowell was a brilliant writer with the ability to draw readers into his vision: “Viewed under suitable conditions, few sights can compare for instant beauty and growing grandeur with Mars as presented by the telescope. Framed in the blue of space, there floats before the observer’s gaze a seeming miniature of his own Earth, yet changed by translation to the sky.”

As to who the beings were who built the canal system, he could only speculate: “Amid the physical surroundings that exist on Mars, we may be practically sure other organisms have been evolved which would strike us as exquisitely grotesque. What manner of beings they may be we have no data to conceive… but upon the surface of Mars we see the effects of local intelligence.”

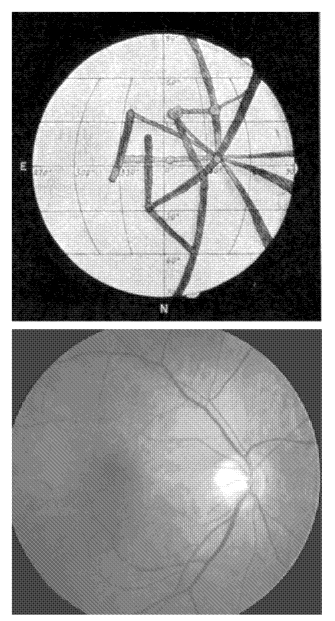

Lowell’s chart of the spokes of Venus and an opthalmoscope photograph of the blood vessels diverging from the optic cup. Image: NASA Astrophysics Data System

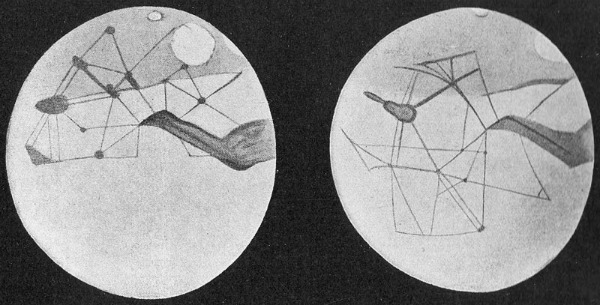

What they built, however, he documented in fine detail, naming as he went: “There turns out to be a network of markings covering the disc precisely counter parting what a system of irrigation would look like. There is a set of spots placed where we should expect to find the lands thus artificially fertilized and behaving as such constructed oases should.”

His calculations were nothing if not precise: “The majority of the spots are from 120 to 150 miles in diameter; thus presenting a certain uniformity in size as well as in shape. To the spot category belong all the markings other than canals to be seen anywhere on the continental deserts of the planet, from the great Lake of the Sun, which is 540 miles long by 300 miles broad, to the tiny Fountain of Youth, which is barely distinguishable as a dot.

“The whole configuration,” he said, “is such as to simulate a gigantic eye which uncannily turns round upon one as the planet slowly revolves. The resemblance to an eye is further borne out by a cordon of canals that surround it on the north.” Remember this paragraph…

Lowell also saw and drew canal-like structures on the planet Venus, which even in those days was acknowledged to be covered by dense clouds. It was, to say the least, puzzling.

Martian canals as depicted by Percival Lowell. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Lowell’s optical technique

To see the canals he used a specific optical technique. Aware that small apertures are less susceptible to the effects of atmospheric turbulence, Lowell stopped down the aperture of his telescope, steadying the image but sacrificing resolution. When it was reduced to 1.6 stops, the lines could be seen at their best.

There was, however, a problem. None of Lowell’s assistants could see the canals other than his secretary, Wrexie Louise Leonard. He claimed this was because she was “a blank slate”, free of preconceived ideas and prejudice. Other astronomers who searched for the canals and failed to find them were clearly similarly prejudiced and subject to his disdain.

Rather than the possibility of life, he said, “they would have snowcaps of solid carbonic acid gas, a planet cracked in a positively monomaniacal manner, meteors ploughing tracks across its surface with such mathematical precision that they must have been educated to the performance and so forth and so on, in hypotheses each more astounding than its predecessor, if only by such means he may escape the admission of anything approaching his own kind. Surely all this is puerile and should be outgrown as speedily as possible.”

A portrait of Percival Lowell. Image: Wikimedia Commons / Mondadori Publishers

Percival Lowell observing Venus from his observatory in 1914. Image: Lowell Observatory / Wikimedia Commons

But other astronomers refused to be convinced and the mounting criticism was devastating to the sensitive Lowell. It took a toll on his health and, suffering from depression, he retired to his father’s house in Boston for a recommended rest cure. The observatory he left in the hands of his assistant, Andrew Douglass, with the task of defending his ideas.

Douglass did just that, for a while. But one day he focused the telescope on featureless globes 1.6km away and saw canals. He unwisely wrote about his misgivings to Lowell’s brother and when Percival returned well recovered he fired Douglass.

But his confidence in canals was shaken. He retracted his claim they were on Venus but stuck to his Martian story. He also found “cracks” on Mercury and strands on the moons of Jupiter. Oddly, they always seemed to reproduce the pattern of the Martian canals.

An astronomer named William Denning lobbed the first damaging grenade into Lowell’s findings. With an extremely small aperture, he said, a lens will display irregular circles and radial lines on our retina.

It took an astronomer who was also an optometrist to pitch the final grenade. Sherman Schultz from Manchester College found that a pinhole of light entering the eye revealed the presence of pre-cataract markers in a radial pattern closely resembling Lowell’s Martian canals. By stopping down the telescope so severely, Lowell had effectively converted it into an ophthalmoscope used to examine the interior surface of the eye.

Lowell, it seems, had written three books detailing the vascular system of his eyeballs. He died in 1916 of a cerebral haemorrhage resulting from severe hypertension.

There is a postscript to this story.

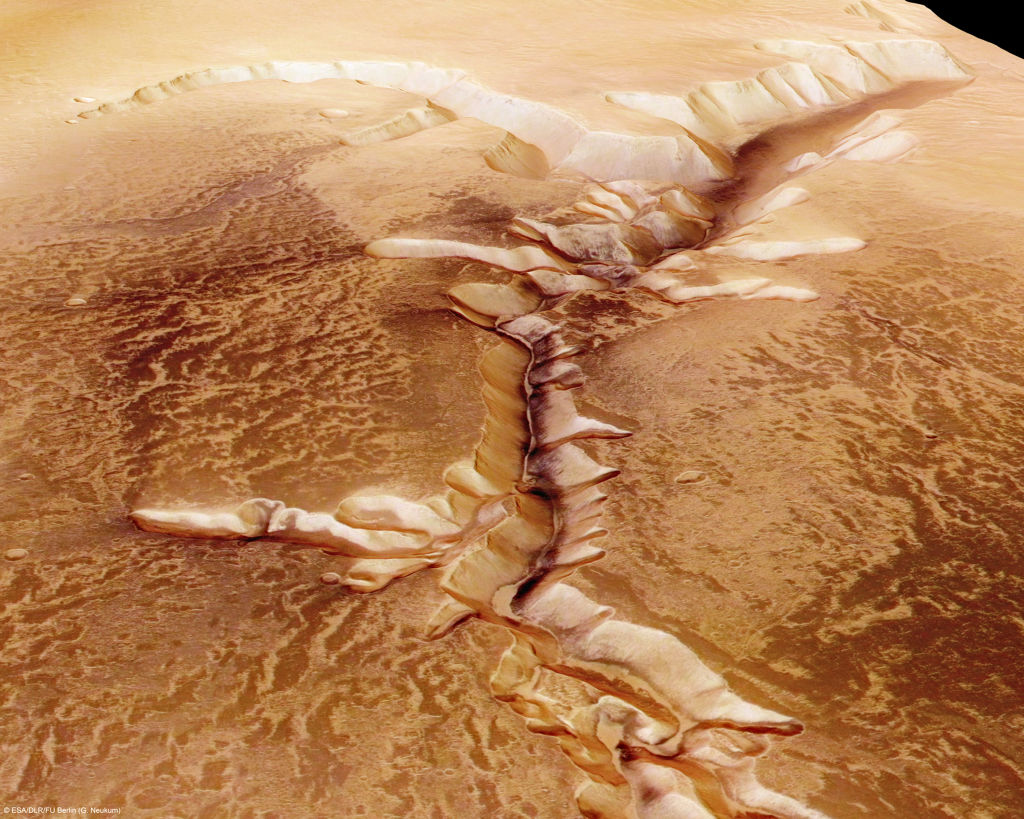

In this handout image supplied by the European Space Agency (ESA) on July 16, 2008, The Echus Chasma, one of the largest water source regions on Mars, is pictured from ESA’s Mars Express. The data was acquired on September 25, 2005. The dark material shows a network of light-coloured, incised valleys that look similar to drainage networks known on Earth. It is still debated whether the valleys originate from precipitation, groundwater springs or liquid or magma flows on the surface. Image: ESA via Getty Images

Seeking to map the “canals” of Mars, Lowell had postulated that a wavelength shift from either side of a celestial object would indicate it was spinning. This was confirmed by astronomers who continued to work at his observatory after his death. The phenomenon became known as the Doppler shift, the change in frequency of a wave in relation to an observer moving relative to the wave source.

It would lead to the most fundamental revelations of the 20th century — that we live in an expanding universe and that spiral nebulae are “island universes” flying apart from each other at enormous speeds. It’s a shame that Percival Lowell wasn’t around to pick up the kudos. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Really enjoyed this insightful essay. Taps into my love of physics/astrophysics/cosmology/astronomy… Thanks for writing it.

Ismail’s post says it all. I can only add my own thanks for the 10 minutes’ enjoyment that I experienced while reading it and studying the beautiful pictures.