MATTERS OF THE ART

Songezo Zantsi: IINKUMBULO – an artist’s personal reckoning with South Africa’s peripheralised histories

Songezo Zantsi’s first solo exhibition, Iinkumbulo, derives from archival shots of the Bisho Massacre and complicates the South Africa's history by underlining stories not to be forgotten.

Songezo Zantsi’s first solo exhibition, Iinkumbulo, presented by Vela Projects in the makeshift space on Shortmarket Street in the heart of Cape Town, was a body of 13 oil paintings and one mixed-media work on paper. Most of the paintings are derived from archival shots by seasoned South African photographers like Greg Marinovich and João Silva, who documented the Bisho Massacre in the Eastern Cape, which took place two years before the birth of the multicultural democracy that is South Africa today. A few of the sourced images came from the artist’s family photo album. Zooming in on anecdotes often overshadowed by the grand narratives of “a post-apartheid memorial complex” of resistance and liberation, and the glorification of the “miracle” reconciliation as authored by the ruling ANC, the artist complicates the nation’s history by underlining stories he believes must not be forgotten.

Through compositions dealing with the artist’s early childhood against a backdrop of a nascent national reformation, Zantsi accentuates that developments in history do not always follow a linear course since many things occur simultaneously.

In the sparse exhibition space, the first artwork to draw my attention was a painting of elderly women beating another woman lying on the ground. She is defenceless, almost lifeless, yet the barrage of sticks continues to pound on her. I cannot tell on which parts of her body the makeshift weapons will land as there is no order to the gruesome act. The violence in the scene contests all the characteristics society stereotypically ascribes to femininity – forgiving, nurturance, tenderness, humility, understanding, etc. The act of violence transcends gender, and race in the case of apartheid South Africa.

‘Abafazi 1’ (2022), oil on canvas, 79 x 69 cm from ‘Iinkumbulo’ by Songezo Zantsi. Image: courtesy of Vela Projects

I later learnt the victim was being accused of spying for the ANC by members of the Inkatha Freedom Party. Such mob justice was also meted out to spies of the apartheid regime by the ANC and others. In search of answers as to why oppressed people would behave in this manner, I am thinking of the catastrophic effects of trauma, victimisation and violence on the individual and society’s collective psyche. I am thinking of how the oppressed transmit and circulate learned forms of subjugation, turning them into a societal culture.

With that in mind, I am reminded of that scene in Njabulo Ndebele’s The Cry of Winnie Mandela, in which, while speaking to her alter ego, Winnie asks: “Did I become your daughter, Major Swanepoel?” She was supposedly posing this question to Major Theunis Swanepoel, an officer of the apartheid regime who had subjected her to torture in a prison cell in Pretoria, an act that might have transformed her to replicate the violence through the infamous Mandela Football Club. I am also reading this painting through Frantz Fanon and Paulo Freire who opined that the oppressed tend to mimic the oppressor, and transmit the violence visited upon them, for the women in this painting are likely to have witnessed or been subjected to the brutal violence of the apartheid regime.

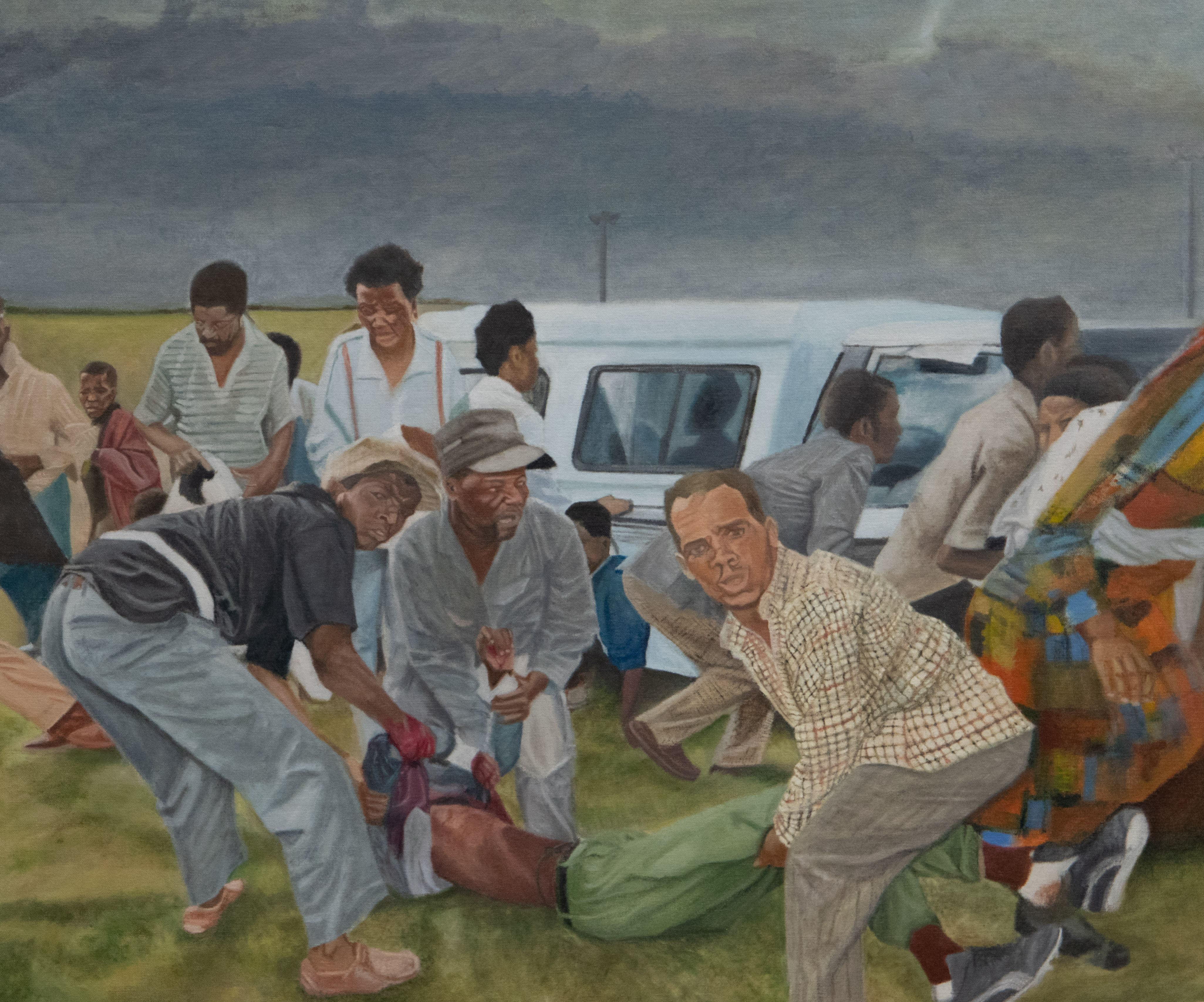

The above scene appears in a painting titled Abafazi 1. Scenes of violence are replicated in Ungalibali 1 and 2. In Ungalibali 1 three men seem to be lifting an injured or dead body, while people in the backdrop are scattering in all directions. Two of the men’s gaze back at the viewer and the other one’s focus in the distance are unsettling. There is fear in their eyes. There is also an element of urgency in the haphazard way they are lifting the body. The gazes of the subjects draw in the viewer who cannot help but feel like they are the perpetrator of the violence.

In Ungalibali 2, three Black police officers are lifting the body of an ANC activist as is symbolised by the yellow and green mask draped on the victim’s face. This looks like a clean-up operation described in Boipatong: Ghosts of a massacre, a story by Monako Dibetle chronicling his father’s experience while serving as a police officer in the apartheid establishment. He felt used. He suffered many years of trauma while working on the frontline, with the Boipatong Massacre haunting him the most. “We were basically cleaning up the mess for the Boers and the Zulus so that they can run away with murdering our people,” the father sadly stated.

‘Ungalibali 1’ (2022), oil on canvas, 94 x 77 cm from ‘Iinkumbulo’ by Songezo Zantsi. Image: courtesy of Vela Projects

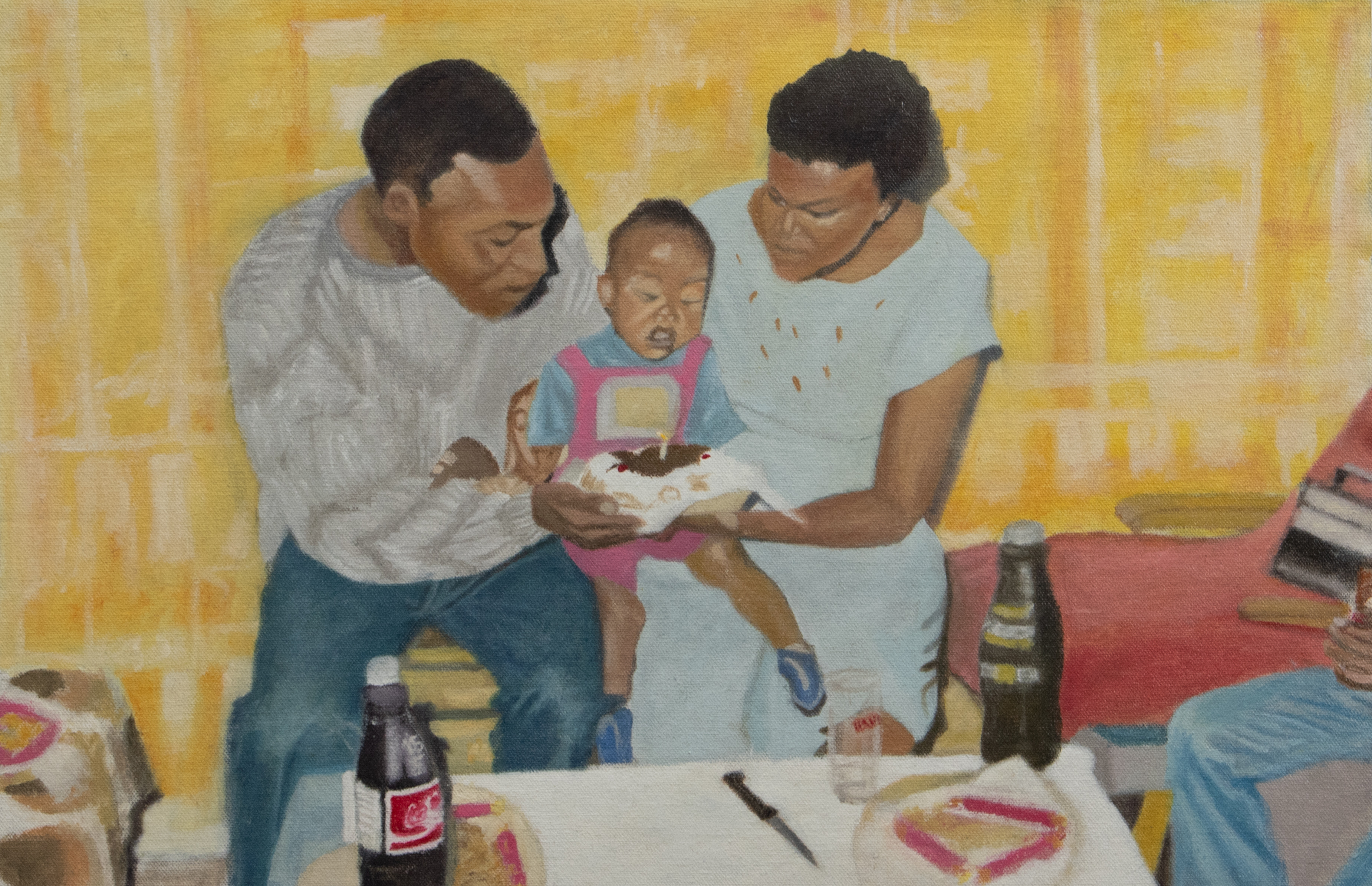

Zantsi’s debut show was not just about violence. In the exhibition a series o positive life memories were placed side by side with portrayals of sad episodes in what the artist remembers of his childhood. In Usapho, a young Songezo, cake in hand and ready to blow the birthday candle, is flanked by his parents. In their modest home, the three are ready to celebrate. The scene is possibly happening in the presence of family, as indicated by parts of an uncle’s legs to the right.

Juxtaposed with this happy moment is Abafazi 3 – referencing the Boipatong Massacre – in which a lifeless toddler lies besides the two sad women folding their arms – a sign of shock. One woman looks sideways and the other downwards as though to emphasise the African belief that we should never look the bereaved in the eye. In Sisonke, three siblings play games on the pavement. It is how they take care of each other. Yet, in Abafazi 2, an elderly Black woman is teaching a white kid how to paint. This is the same care that the siblings playing on the pavement never got to experience as their mother probably left them to go and take care of kids in white suburbs to earn income to look after them and possibly afford to send them to school. Through these scenes the artist engages troubling power and labour dynamics in apartheid and present post-apartheid South Africa, as well as daily life.

‘Abafazi 3’ (2022), oil on canvas, 60 x 40 cm from ‘Iinkumbulo’ by Songezo Zantsi. Image: courtesy of Vela Projects

‘Usapho’ (2022), oil on canvas, 60 x 40 cm from ‘Iinkumbulo’ by Songezo Zantsi. Image: courtesy of Vela Projects

Completing Zantsi’s impressive body of work are two colourful compositions that engage the economy through two interesting narratives. In Ciskei, the artist presents two white men draped with the British and the apartheid flags pulling the cow in the middle in one direction, while a Black man masked with the ANC flag pulls in the other direction. The latter’s posture suggests he is losing the tug-of-war. The ground over which the three are tussling is the homeland of Ciskei as signified by the sky-blue and white flag of the Bantustan, with the cow replacing the flamingo as the centrepiece. Also conspicuous in the frame are the shadows of the subjects as the tussle happens in broad daylight. Through the work, the artist appears to be commenting on the force used to disenfranchise the locals of their wealth. Interestingly, the work leaves the viewer unable to make a conclusion as the rope pulling the cow from the front is assigned to an imaginary figure outside the frame.

The irony of Christianity, a religion that helped soften the hearts of Africans and prepared them to accept colonial subjugation with little resistance, turning to be the saviour of the disenfranchised through self-help projects is not lost. It is portrayed in Iimizamo, in the form of a Black Catholic sister seemingly blessing the two female vendors going to trade for the day.

Through this body of work, the artist is not claiming to know more than we do. However, it bothers him that he did not encounter the sad episodes of the Bisho and Boipatong massacres in the history curriculum at school. As such, the process of him digging up the archival images, and coming up with compositions that combine figures and scenes from multiple sources, is his way of finding out more about these sidelined histories. It is his way of understanding what transpired.

Therefore, to Zantsi the process of painting is also a methodology of seeking out the truth. In portraying these narratives, the artist hopes to draw the nation’s attention to a specific phase in South African history which appears to have been deliberately pushed out of the carefully curated mainstream nationalist narrative. He hopes his intervention will help resuscitate interest in the history of the massacres which remain confined to the oral record and only occasionally enter the written discourse, as well as counter the political point-scoring synonymous with government-led commemorations. It would be interesting to gauge the reaction of the audience if this body of work were to be exhibited somewhere in the Eastern Cape, the epicentre of the massacres in question. DM/ML

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti is a PhD candidate in Art History in the NRF SARChI Chair programme in Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa, Rhodes University. His PhD research is partly funded by the Rhodes University African Studies Centre through its funding from the DFG, the German Research Foundation under Germany’s Excellence Strategy.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I stumbled upon this exhibition, and I was astonished I had not heard of this new painter. The paintings were arresting and disturbing. What struck me was that Zantsi applied the same eye for detail and even paint application in both the personal memories and the images from media photography. To me, it revealed an earnestness in his search for true narratives. Remarkable exhibition and an artist to watch.