PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

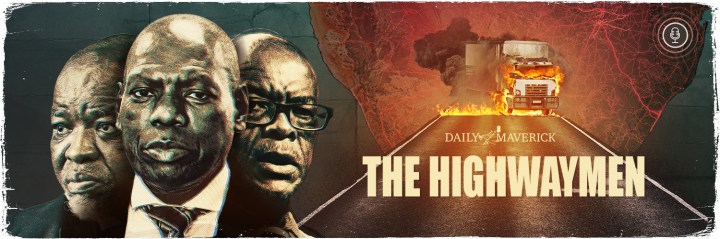

The Highwaymen Episode 8: Democracy is a funny thing

In December 2022, the 55th – and possibly last – elective conference of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress will take place against a backdrop of sociopolitical chaos. In the limited audio documentary series, ‘The Highwaymen’, investigative journalists Richard Poplak and Diana Neille take a road trip across South Africa in search of answers to how the country got to this breaking point, and how the lives and careers of three senior ANC figures – Ace Magashule, Gwede Mantashe and Dr Zweli Mkhize – may be representative of the rise and stumble of our once vaunted democratic project and, by extension, liberal democracies everywhere. In this final episode of the journey, Neille and Poplak visit the ground zero of the July 2021 uprising: the strategic town of Mooi River. Here, we wrap up our deep dive into the nature of 21st-century liberal democracy, and come to some conclusions on why it appears to be floundering.

Patrick O’Leary: Hi, this is Patrick O’Leary, editor of FleetWatch Truck Magazine. The time is 11:30 and the date is Friday, July the 9th. Guys, we’ve got an incredibly serious situation at Mooi River… At last count there were eight trucks burning. This is an urgent call and a very serious call to get your truck off the N3, do not go near Mooi River.

Matt Nurse: I remember, we were kind of a little bit on the back foot, we didn’t really listen to any of the rumours that had been going around… We had heard talk of certain things happening… To the exact extent, we didn’t realise.

Being where we are, geographically, we have… A logistical artery, here at this [Mooi River] toll road, which I think was very strategically pinpointed, as we have all come to realise. We’ve become quite naturalised to the fact that one or two trucks might be bombed on a weekend.

On [the] Friday… When it all started… It ended up being upwards of 20 vehicles in the one evening that were bombed.

News clip: I’ve just spoken to officials, they’re saying 19 trucks have been burnt here at the toll plaza, a further six on the N3 by supporters who are throwing their weight behind former President Jacob Zuma…

Diana Neille: Follow the ley lines of strife, and you’re bound to end up at Mooi River, a town with a population of 20,000 or so – but more importantly, a truck stop and toll plaza that’s the busiest in the country, processing thousands of long-haulers each week. It marks roughly the 140km point from Durban to Johannesburg, along the N3 artery.

If the N3 is South Africa’s spinal column, Mooi River is its chronic lower back pain. And as local business management consultant Matt Nurse recounts, it’s where the violence of July 2021 was sparked.

Matt Nurse: It’s very evident that Mooi River has slowly gone from its heyday… Where employment was fruitful and, you know, trade was happening, to a slow degradation of standards in all these areas, which has invariably left us in the situation that we’re in. And I think, unfortunately… With the catalyst was, was really, again, down to opportunity[by] those that are desperate… Which is the saddest part.

Diana Neille: We’ve driven up the N3 from Pietermaritzburg, inland to Mooi River, to meet with a group of local business owners who led what effectively became a small civilian army over five days of the uprisings, protecting their town from looters and arsonists – or, to put it another way, from their neighbours.

Unwittingly, they became the lone protectors of a major logistics hub, one that is hit time and time and again by a range of mafia players trying to assert control of the N3 highway. We think of the highway as the country, and perhaps the planet, in miniature: There is the formal highway – the one you can see, with goods and commodities and holidaymakers travelling from Johannesburg to Durban and back again. Then there is the informal highway – a dark hub for heroin and guns and other illicit goods, all of it running up from Durban’s poorly policed port, into the wilds of Joburg.

Who controls this highway? Well, exactly. We’ve reached the seventh and final point on the continuum, where organised criminality devolves into an all-out gang war, and where democracy takes a selfie with whichever Russian oligarch comes to sunbathe at his vast Cape Town mansion.

For the residents of Mooi River, back in July 2021, the speed at which their town was overrun by forces which seemed organised was a wake-up call.

Matt Nurse: Monday morning came… We realised it was… a lot more serious than we had… we had thought. The question was, then, is there anything that we can do, to stop [the] carnage.

Richard Poplak: Mooi River is perhaps best known as the hometown of supermodel and Victoria Secret “angel” Candice Swanepoel, who was recently pictured showing off her bikini bod on some unnamed beach in paradise.

Her hometown does not have a bikini bod. It’s a rough-edged former manufacturing and farming base, Many of its roads are now rutted, its corners occupied by listless bodies. It’s clearly fallen on hard times.

Lincoln Waite: Mooi River, I would say, is in two parts; and so you’ve got the Mooi River town, then you’ve got Bruntville, which is the community across the road, and they’re the… they’re the bulk of the workforce.

Richard Poplak: That’s Lincoln Waite, who owns the local Spar supermarket. He invited us to come and meet with him, his son-in-law, business consultant Matt Nurse, and his friend, Gordon Odell, who runs a business supplying local farmers.

They’re joined by Mzwandile Nconco, the chairman of the local branch of the ANC, who runs his own security company that protects local businesses, including the Spar, from the ANC – or, more pointedly, from the ANC’s unravelling.

It’s a sweltering mid-February day, and we sit around a conference table on the second floor of the Spar, overlooking the bustling store beneath us. We mainline bottles of water and catered sandwiches, and talk for hours.

Lincoln Waite: Historically… The employment came out of a cheese factory, a milk factory; there was a big textile industry, which has now dwindled… So, the community unemployment obviously rose and we basically rely on local farming at the moment, as our main industry in this… in this area.

Richard Poplak: What I’m hearing is that this is almost a typical South African story. You have deindustrialisation.

Lincoln Waite: Yes.

Richard Poplak: You have labour unrest.

Lincoln Waite: Yes.

Richard Poplak: You have a shrinking economic base.

Lincoln Waite: Yes.

Richard Poplak: You have consolidation in the agricultural sector. And so, what’s left, effectively, is services.

Lincoln Waite: Yes.

Richard Poplak: Big brand stores selling stuff to the local community.

Lincoln Waite: And I mean, with that, obviously, the unemployment. So we rely heavily on grants and pension, basically. And I mean, I don’t know how sustainable that is… For how long we can survive.

Richard Poplak: This, then, is the inevitable result of economic policies crafted two decades ago, during the Mbeki era. One: A neoliberal embrace of austerity and open markets that supercharged the financial sector and little else. Two: A subsistence grant programme that created a low-level consumer base. Three: Cartels of apartheid-era capitalists who owned and controlled the formal economy. Four: Union bosses co-opted by the forces of elite capture, who in turn became ganglords, insisting, “accept our terms or else”. And five: The constant theft of municipal resources, so that the town’s infrastructure, like the country’s, crumbled.

South Africa no longer makes anything – it only mines commodities, offshores wealth and shops.

As a result, Mooi River is one of the planet’s new post-employment dead zones. Outside of working at places like the Spar, and a bit of farm work, there is – very simply – nothing to do here.

Then there’s the political history, which – as always – refuses to relinquish its hold on the present. Here’s Mzwandile Nconco on what’s unfolded here over the years.

Mzwandile Nconco: When the violence started in 1990, in Mooi River. There were two factions, there was IFP and there was ANC. So that’s how it all started. That’s how the demise of the factory, Mooi River Textiles, started. You know, the fights, the violence and everything. Eventually, people from Mooi River could not go to [Mooi River Textiles] because of IFP guys, because they were heavily armed, assisted by the police in that time.

Richard Poplak: Okay. So in other words, there is a history of political violence here in Mooi River, going back to the bad old days.

Mzwandile Nconco: Oh definitely, definitely. In 1990s, round about then.

Diana Neille: There’s one more factor that comes into play here. And that’s South Africa’s rampant, unrelenting, politically endorsed anti-African xenophobia – the right-wing populism, endorsed by the ANC and others, intent on scapegoating African migrants.

News clip: A spate of violent attacks have rocked the road freight industry recently. Scores of trucks have been torched or vandalised, while the attacks are fuelling tensions between South Africans and foreign truck drivers.

Diana Neille: The Mooi River truck stop has been the site of frequent violent attacks over the past several years. We spoke to a Zimbabwean driver called Forward, who was on the road when the #ShutdownKZN uprising began. For safety’s sake, he would only give us his first name.

Forward: KZN, yoh. It’s another country… To drive truck here… N3, it’s a very risky job. You meet a lot of things in the road, like people [who] want to hijack you, like people who are saying about foreigners, they must come out from our job. When you’re driving, you mustn’t stop anywhere, you have to stop only at a safe place, and sometimes, don’t show yourself [that] you are a foreigner; just try to protect yourself.

It’s a very difficult thing.

Diana Neille: The campaign against foreign national drivers is directed, at least in part, by a hyper-nationalist association called the All Truck Drivers Foundation. Like many of the so-called business forums that have emerged across sectors in recent years, these are effectively racketeering outfits, who try to insert themselves into, and violently disrupt, industries already saturated by established players.

News clip: South African truck drivers heeded a nationwide call to stop trucks from operating, in protest against the employment of foreign drivers.

News clip: A group calling itself Delangokubona continues to terrorise workers at different construction sites, demanding government contracts.

News clip: A forum of businessmen in KwaZulu-Natal has pledged its support for former president Jacob Zuma ahead of his court battles. The Radical Economic Transformation champion says it respects the rule of law and upholds the notion of innocence until proven otherwise.

Diana Neille: These forums are an attempt, made very much in step with factions of the ANC, to gangsterise the economy. At every point along the supply chain, there is now someone with an AK47 waiting to claim what the Russians call blat – favours.

Songezo Zibi, former editor of Business Day and founder of the think tank, Rivonia Circle, is pretty forthright on this point.

Songezo Zibi: In the mining sector, you’ve got these business forums, who are affiliated to… different parts of the party, or elements in the party, who demand a slice of contracts in the mining sector, in the construction sector; you already had the trucks down the N3, being stopped and burnt, and that sort of thing.

And so these criminal elements have… are embedded, they’re now one and the same, with the ANC. So what you have is a gang war… And that gang war, because it is in the political sphere, needs mass support, and that is how you end up with an insurrection, as it were. Because, let’s be honest, the person who was formerly president of South Africa was running a criminal enterprise.

Richard Poplak: This is tied to the degradation and destruction of the state-owned Transnet railway network, which has been gutted by organised corruption at the top, and organised stripping of hardware at the bottom.

This year, copper theft alone cost the South African economy more than R45-billion, according to a study by Genesis Analytics. Just in April, Transnet was attacked 123 times and 40km of copper cable was stolen.

Lincoln Waite: One of the critical things… So we have unemployment, but now we’ve got this added cost of transport, because our railway is defunct. And the reason the railway is defunct is because of crime. Simple!

Richard Poplak: Well, it’s more than that. It’s the fact that the SOE was hollowed out from the top.

Richard Poplak: That’s gangsterism, at a..

Matt Nurse: … a very high level.

Lincoln Waite: Ja, but you need to get the trucks off the road. You need to get the… Freight back onto the rail, which is far more economic, we all know that. So, we need to address these things.

Richard Poplak: In other words, this status quo works for a political elite and their factions who have helped turn South Africa into a gangster state.

Mzwandile Nconco explains how he saw this first-hand, from inside the party at a local level, in the lead-up to Zuma’s incarceration, and the resulting chaos.

Mzwandile Nconco: You know… Way before that, I did call the meetings, the secretaries of all the wards, I did call them to my office; let’s discuss this thing, before they get out of hand. Let’s talk to people. Only one of them came, the rest did not come. I think it was a week before, because the rumours were there. The writings were on the wall – we could’ve prevented it.

Richard Poplak: Well, I mean, surely that speaks to some residual level of support for Jacob Zuma?

Mzwandile Nconco: Ja, definitely.

Richard Poplak: The contestation within the ANC plays out in Mooi River as a standard gangster movie turf battle. But, in case we’ve forgotten, the ANC is a political party, which has won six successive parliamentary majorities, and has a mandate to govern the country. This turf war rips the entire veneer of democratic governance to pieces – there is no possibility for what is traditionally called a representative democracy under these conditions.

Here’s our interview with Songezo Zibi again.

Richard Poplak: I found something very interesting that emerged from this deep dive, that President Ramaphosa commissioned into… The “insurrection”… Last July. One of the interesting paragraphs – this report was overseen by Professor Sandy Africa.

Songezo Zibi: Ja.

Richard Poplak: And the paragraph that I think has jumped out to everybody is that “contestation within the ANC has now become a national security threat”. In other words, the factional battles happening within the ANC pose a threat to the durable nature of our democracy. That, to me, is astounding: That we’ve come to the point where the fights within the ANC are no longer fodder for front pages, they’re actually a national security threat.

Songezo Zibi: Honestly, I’m stunned that it needed this task team to happen. It’s ridiculous. I mean, our security agencies are, either on the payroll of criminal elements, organised crime, tobacco cartels, and the like; they’re either in service of the politicians, and for the rest, for those who try to do a professional job, they were kicked out, and they continued to have serious obstacles.

In which country on this planet does $50-million disappear from the headquarters of the National Security Agency? Just think about that! If that doesn’t tell you that you’ve got a problem, then I don’t know what does.

Diana Neille: Zibi is referring to the fact that, under Zuma, the State Security Agency was used as a piggy bank for personal enrichment – at least $50-million was stolen – but also to build a network of spies and black helmets that zipped around in the shadows, doing Zuma’s bidding.

Here’s intelligence inspector-general Dr Setlhomamaru Dintwe, testifying about this at the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture.

Dr Setlhomamaru Dintwe: What I can confirm is that money has been stolen and we are talking lots and lots of money… There is evidence in our possession that some of those monies were used to finance a particular faction within in the governing party, and in other jurisdictions you will find that these monies can be used also to finance terrorism.

Diana Neille: This is straight out of the Russian playbook – Zuma, a former intelligence operative, took full control of intelligence operations, much like Vladimir Putin and his men used the KGB, and then the FSB, as a money funnel.

The meltdown, when it happens, happens quickly.

This is Waite and his team on what unfolded when the South African Defence Force finally arrived in Mooi River, after they’d been defending their community alone, day and night, for days.

Lincoln Waite: Gordon was asking, ‘when is the army coming? When is the army coming?’ And they said, no, they want to know if we’ve got an infrastructure for them; in other words, we must have…

Gordon Odell: … supply them with accommodation, and…

Lincoln Waite: … accommodation, and they need to know da da da da. So they’re an hour away in Ladysmith… It took them four days to get here. They arrived on the fourth day, because they were…

Richard Poplak: …underresourced.

Lincoln Waite: Well, ja, they were here…

Matt Nurse: Exactly what it is.

Lincoln Waite: … but they had no food, they had nowhere to stay…

Matt Nurse: We fed them.

Lincoln Waite: … They had no water, they had no ablution facilities; it was an absolute shocker. It was a nightmare.

Diana Neille: Private citizens feeding and garrisoning the army – the same army that had ostensibly come to save them. Combine this with the policing crisis – you know, the fact that the SAPS barely showed up for the riots – and it’s clear that Zuma’s attempt to break down the state worked.

In terms of drawing explicit links between South Africa and the gangster states of the former communist bloc, no one has done more work than government and public policy scholar Ivor Chipkin, who co-runs a think tank called the New South Institute.

While he was at the Public Affairs Research Institute, or PARI, during the Zuma era, Chipkin and his colleagues released a massively controversial study, called the Betrayal of the Promise report. It posited that State Capture was a political project.

Ivor Chipkin: What we began to do – and I think we got the broad contours correct – was to understand that Jacob Zuma presidency, as arising out of a profound disillusionment with the transition; a profound critique of the terms… Of course informed by lots of motives, self-interest, all sorts of things like that. But that there was a political architecture to it: A critique of capitalism, a critique of the transition, as a kind of an elite transition… Which, I think, is very much alive today, in the EFF and parts of the ANC. A very, very strong critique of democracy.

Richard Poplak: And of the Constitution.

Ivor Chipkin: And of the Constitution. So this is what we began to highlight: That this wasn’t just a gang of thugs stealing money. There was a politics here, and that politics was a full-frontal assault on the constitutional and democratic dispensation in South Africa, and we needed to understand that, because it wasn’t just enough to oppose this as a phenomenon of corruption.

Diana Neille: Tragic as it may seem, constitutional democracy hasn’t worked for all South Africans – just as it hasn’t worked for all Americans, or all Canadians, or all Danes.

Mooi River is merely one example, if a perfect one, of a country in which more than 34% of the general population is officially unemployed, and nearly 60% of people between the ages of 18 and 25 cannot find work.

And while it may seem outrageous to think of Jacob Zuma – two-term deputy president, two-term president – as one of democracy’s losers, his populism was premised on being “the biggest little guy”. He was one of the People, with a capital P, with no formal education, excluded from formal institutions, governed by formal white, Western laws that have no application in a local context. He was a victim. A sap. A fall guy.

Poor dude.

But since the mid-zeroes at least, neither Zuma nor his allies – or his rivals – in the ANC never once looked at African history for political alternatives, nor were they interested in creating a new politics based on versions of local communalism. They were chauvinists, not Afrophiles. They had no learning, no curiosity and no imagination, and they never once looked north of the Limpopo for answers. Instead, they focused their attentions elsewhere.

Ivor Chipkin: The Soviet transition, the Eastern European transition, the break-up of Yugoslavia, raises questions for South Africa, which are so profound, and which have – we don’t think – been adequately posed in South Africa.

Everything is highly integrated into these politically controlled networks through, essentially, gangsters, so that you can’t run a business. I mean, I was… we’ve just come back from Serbia, and I was asking people, you know, they were saying the level of control goes down to who’s got a popcorn stand, a vending stand in the streets of Belgrade. All of that is also integrated into those networks.

This is a Putin model of how you run capitalism. You run capitalism politically. You allow businesses to operate, you allow some competition even, but it’s all highly integrated into… in and through political networks. And I think that was very much the Zuma project.

Richard Poplak: Unwinding this project has proved nearly impossible, not least of all because the Ramaphosa regime hasn’t displayed sufficient will. If anything, the project has advanced. The obsession has been the unity of the ANC. But there’s nothing left of the ANC, not as a political entity.

The ANC is dead. Long live the gangster state, and its rules without rules.

Matt Nurse: I’ll never forget sitting in the bath the one evening. The first three days, no one slept, we hadn’t shifted yet, everyone was just here. And then we realised you had to get rest, and go and sleep, and come back. And I remember going, having a bath the one night, and I remember just sitting there with head in my hands… Just thinking, like, what have we come to? I mean, is this it? Is this where it’s going to end? Because, at the time, there was no apparent light at the end of this tunnel.

Gordon Odell: It was just sad that the police and army couldn’t contain it, because if it wasn’t for the civilians in KZN, it would be done.

Richard Poplak: The defence of Mooi River is a typical South African story. It is the tale of a band of mostly, if not entirely, white people defending the brands and commercial institutions of Main Street, like banks, fast food outlets and supermarkets, against groups of desperately poor black people living on the edge, mere minutes from zones of wealth and privilege.

The community of Mooi River may have come out the other side of the unrest of July 2021 relatively peacefully. But in some places, racial animus did explode, forming new wounds on top of old scars.

News clip: To Phoenix, north of Durban, where racial tensions erupted during the unrest last week. At least 20 people were killed, most of them black. People in the area described gunshots, dead bodies and cars being torched. After the looting there were attacks in homes and businesses, and residents in Phoenix set up barricades at almost every intersection. Indian residents often pitted against their African neighbours living in the informal settlements of Bhambayi, Zwelish and Amaoti. Well, a social scientist says the tensions in KwaZulu Natal pose a threat to South Africa’s very democracy, and they stem from issues that have never been resolved after apartheid.

Richard Poplak: But if you think that this type of scenario is only a South African story – the widening divide between rich and poor, black and white – you’re not paying attention.

News clip: St Louis has a police problem. In some of the wealthiest neighbourhoods, sworn officers, with the Metropolitan Police Department – in uniform, riding in SUVs marked “police” – are being offered bonuses for investigating crimes and arresting criminals. But the offers aren’t coming from the taxpayer-funded police department. They’re coming from a private security company called The City’s Finest. That’s just one of the details uncovered in an investigation published this week in ProPublica.

Richard Poplak: As poverty rises, and crime along with it, this is the counterargument to more humane policing, less racial profiling, fewer extrajudicial executions of black men. This doesn’t just happen in Brazil, South Africa, Colombia and Donald Trump’s so-called “shithole” countries – social inequities make private policing, and its manifest injustices, inevitable.

Here’s Heinrich Böhmke on what it means in the long run.

Heinrich Böhmke: South Africa was a shining beacon of democracy, a shining beacon of constitutionalism, of racial reconciliation. Some of those things, of course, were based on chimaeras, but there was also a redistributory politics that, to some extent, was possible. Because, although it is true that the economic policies that are insisted upon by Western investors and financial institutions and so on, have bracketed what could be done, as far as social income transfers to people – especially poor people…

Even within neoliberalism, even within the constraints of neoliberalism, there was R1-trillion that was stolen. And that R1-trillion could have been applied to building schools… Or more police or whatever you want. So even within the constraints of neoliberalism, there was enough money to have made a hell of a change to the fortunes of a lot of people in our country.

So, not only is the failure of the South African project a cautionary tale to where well-meaning democracies end up, once gangster practices start getting presidents in power, who simply tear up the rule books. But it’s also, at another level, a cautionary tale to say that, even within the constraints of a neoliberal economy, they will steal… The 6% of GDP that is set aside for social investment. Even that will be stolen.

Richard Poplak: Once again, it’s left to the benevolence of men with guns – left up to their ability to make rational and humane decisions, and how kind they choose to be to their neighbours.

Matt Nurse: The first couple of days… We were transparent… In the fact that we all were armed, and that we were organised. We all four actually had a meeting, as to how it was that we were going to control this…

Gordon Odell: The biggest thing, for me, was trying to get youngsters who watch YouTube videos all the time, and they just want to shoot and frickin’ let rip. And… In a situation like that, I tried to explain to them, we’re not law enforcers, we’re here just to protect what’s ours, and we’re here to help the police. So, we were in no way an attacking force. Everyone just banded together.

And then, obviously a big issue was, nobody could get any food. Stores were closed and people with young kids, they had no nappies. It was an absolute nightmare. And Lincoln came in here, and he allowed people to come into the store. They didn’t even have to pay, they could come back later and pay, because nobody had any money. So it was a big community thing. And for me, the whole episode actually brought a lot of people closer together, if you know what I mean. And I think a lot of people agree with me there.

So, within all the turmoil, a lot of good happened. Because good always comes out of bad.

Richard Poplak: As Lincoln Waite and Mzwandile Nconco put it, the poor of Mooi River have been weaponised by people with other motives.

This is what makes the town, and the country in which it is a symbol, a cautionary tale for the rest of the world.

Mzwandile Nconco: There’s a perception that people outside of Mooi River, they also use Mooi River to plan the attacks, coordinated things… Because they know when people are hungry, when people are unemployed, they’re easy. If they see a burning truck, a hijacked truck, easily people go to that truck and take whatever they can take.

But I strongly agree, it’s organised from outside; then they use Mooi River to attack whatever they want to attack.

Ivor Chipkin: What I think is very important – and this is what really, really scares me – is that this contestation is finding a political language. An expression as a different vision of democracy. I think it’s a deeply authoritarian view. So what you’re beginning to hear is a fundamental repudiation of South Africa’s constitutional democratic model in favour of something which they called popular democracy, a more majoritarian view of democracy.

Jacob Zuma used to lament that the constitutional dispensation had fundamentally excluded black majority rule, because now, you know, majority parties were subject to this Constitution, which kept overruling the ANC, and its decisions, that’s not what the ANC fought for, he says.

So they may well be, in practice, destroying institutions, violating the constitutional principles, breaking and subverting democratic processes. But they’re not doing it just because they’re criminals. They’re doing it because they feel righteous and justified doing that, because they’re acting with a sense of political courage. They’re breaking this framework, which is deeply constraining and discriminatory against black South Africans generally and Africans in particular. So there’s a kind of righteousness in this violence; there’s a righteousness in this. In this disruption and this breaking.

Richard Poplak: That’s an increasingly prevalent political impulse – it’s what drove Brexit in the United Kingdom and MAGA in the United States, to name but two examples. Burn it all down, baby.

In the gaps come community activists like Zain and Mohammed, or the crew in Mooi River, or the Highwaymen and their legions. This is the thing about the Highwaymen – they’re a naturally occurring phenomenon. The vacuum must be filled.

Meanwhile, in emergency situations here in South Africa and elsewhere in the developing world, where governments can barely deal with day-to-day governance, NGOs step in, replacing bureaucracy with benevolence.

Dr Imtiaz Sooliman: Dr Imtiaz Sooliman, chairperson and founder of Gift of the Givers. I never got up one morning to form Gift of the Givers. It never was something that was born in my own head.

Diana Neille: Gift of the Givers, a famous emergency services NGO, was founded by Sooliman as part of a spiritual calling, back in the early 1990s, during the first Gulf War and the troubles in Bosnia. After those emergency interventions, Sooliman, who is South African, started setting up primary healthcare clinics in areas that the apartheid regime had deliberately ignored.

Due to a never-ending stream of human and natural misery, the organisation grew, and grew, and then grew some more. Somehow, nearly 30 years later, South Africa is still in need of constant emergency ass-wiping, and Sooliman has become a celebrity activist, lauded in the press as South Africa’s de facto president.

Does a functioning state require an NGO to provide services like water and sanitation before, during and after emergencies?

Probably not.

Richard Poplak: Dr Sooliman, it strikes me that when you speak of your work in water, sanitation, healthcare, engineering, service delivery, Gift of the Givers functions as an alternative state.

Dr Imtiaz Sooliman: That’s what people tell us, you know, that the government should learn from you. We don’t like to be seen like that. There’s a strong anti-government sentiment, because of load shedding and corruption. But remember I come from a spiritual background, and from our spirituality we are taught not to run people down.

All the people in government are not bad. Their systems are a problem, and they’re not skilled in disaster. And I tell the government all the time, and they laugh, you know, because I’m so blunt with them. I tell them, your disaster intervention is a disaster on its own, you know, it’s a mess. You guys have got too many different people.

Richard Poplak: Well, I think, most modern technocracies are not built for disaster management, because of the belief in austerity measures, the belief in funding as conservatively as possible. So, what strikes me, and I’m sure Diana as well, is that you step into the fold, to deal with the fragility of these systems. And I’m not sure how sustainable that is. I mean, I find it quite scary.

Dr Imtiaz Sooliman: I have always one policy. Have we succeeded in everything that we’ve done? Yes. Have we been getting more support? Yes. Are our systems getting better? Yes. So we’re not dependent on the government. And my call has been – since the time of the unrest – it’s time for active citizenry. That the country as a whole has to take ownership of the country. Yes, it may not be the right thing to do, but under the circumstances, when the ruling party is fighting itself, we can’t let the country fall apart.

And you’ll see, over the last year, the intervention and the support from corporates has become huge, to fix government facilities, to fix water, to fix hospitals, to fix schools. And people themselves are fixing potholes, cutting the verges.

Richard Poplak: Is it something that we should embrace? Is it something that, again, is maybe a little menacing in the fact that private organisations, who are effectively unaccountable to South Africa – and I’m not suggesting that our politicians are accountable to us, but they are our representatives – are now filling in, to do the role of our government?

Dr Imtiaz Sooliman: We have to bear one thing in mind, Richard, that the taxes of seven million people can’t help 60 million people. That’s the reality. A health system that’s collapsing, an education system that’s collapsing, infrastructure is collapsing, roads that are not working. There was no planning, no management, no maintenance; all that together has come at a time to haunt us, in 2022. But this is where corporates can play a big role, and they are playing a big role. They said, how can we fix the country? Don’t worry about the forms, and about a tax certificate and our branding, and this, that and the other.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. With the economic crisis, with job losses, with Covid, with so much companies closing (sic), we took in the biggest amount of money in our history. People are serious, corporates are serious about saving South Africa.

Richard Poplak: Well, thank the ANC for one thing: It seems that corporates have finally woken up to the fact that the short-term benefits of collaborating with the state have met the realisation that you cannot sell your products or services if the customer base is either broke or dead. That said, despite Gift of the Givers’s undeniable good works, and despite all of the good intentions suddenly flooding in from major corporates – who for years have been engaging in transfer pricing, off-shoring their wealth and lobbying for lower taxes – there is something undeniably dystopian about a democracy relying on NGOs, or worse, an insurance company, to fix potholes or feed the elephants.

Our seven-point programme – from ideological contestation, to divisions, to factions, to corruption or elite capture, to State Capture, to organised crime to gang war – in South Africa, this process has run its course.

Diana Neille: This story reminds us, however, that while many people suffered and died for it in South Africa, democracy is not a static condition. Like a dream after waking, it is constantly receding, evaporating. By design, it creates the conditions of its own fragility. It demands inputs from good actors with no time or energy to provide them, and has no means of refusing the entreaties of those seeking its destruction. Its pliancy is its strength, and also its weakness – and that weakness is itself a strength. As the political analyst Astra Taylor notes: “I don’t believe democracy exists; indeed, it never has. Instead, the ideal of self-rule is exactly that, an ideal, a principle that always occupies a distant and retreating horizon, something we must continue to reach toward yet fail to grasp.”

Richard Poplak: As we make our way back to Johannesburg, it’s time to consider what comes next – how to reach with more intention, and greater will.

What then would constitute a rebirth? DM

The Highwaymen credits:

Written, produced and directed by Richard Poplak and Diana Neille.

Fact-checking and editorial oversight by Sasha Wales-Smith.

Editing and sound design by Diana Neille, Bernard Kotze and Tevya Turok Shapiro.

Original soundtrack and visual aesthetic by Bernard Kotze.

Additional music by Janus van der Merwe.

Additional voice work by Ayanda Charlie.

Transcriptions by Gloria Cooper.

Project manager: Kathryn Kotze.

Marketing lead: Sarah Koopman.

Editor-in-chief: Branko Brkic.

Deputy editor: Jillian Green.

Executive producer: Styli Charalambous.

Produced with support from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

(The content may not necessarily reflect the foundation’s views or opinions.)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.