LITERARY LANDMARKS

Uncertain times revisited — ‘Ulysses’ and ‘The Waste Land’ 100 years on

After the appearance in 1922 of ‘Ulysses’ and ‘The Waste Land’, the novel and poetry were irrevocably changed. While the works were committed to representing life in all its harshness and drudgery, they did so in a way that displayed extraordinary verbal virtuosity and beauty, that leavened the unpalatable without avoiding or suppressing it.

As 2022 draws to an end, in uncertain times with the world facing pestilence, war and potential widespread hunger, a glance a century back to 1922 takes us to a time that was perhaps experienced as even more chaotic and uncertain.

That year combined upheaval and crisis, but also witnessed momentous cultural and literary landmarks.

In South Africa, a communist-inspired white mineworkers’ revolt was put down with considerable force at the beginning of the year. It was also the year that the world’s largest broadcaster, the venerable British Broadcasting Corporation, was founded. In the latter half of 1922, Joseph Jughashvili, better known to the world as Joseph Stalin, exploited the power vacuum left by Vladimir Lenin’s declining health and consolidated his position as the dominant figure in Soviet politics, with fateful consequences for the peoples of the Soviet Union.

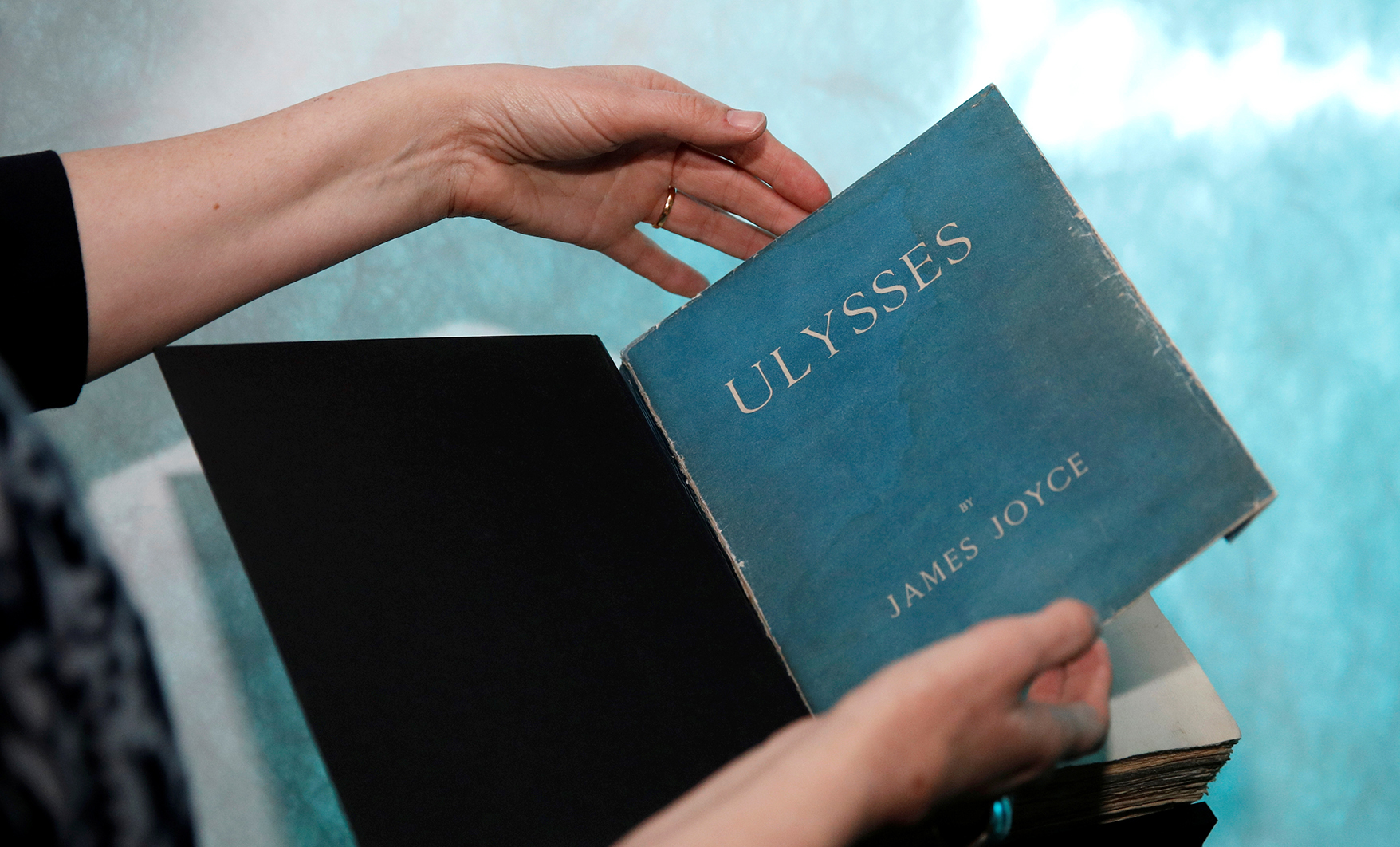

From a literary point of view, the same year saw the publication of the two towering landmarks of 20th-century literature: In February, James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was first published as an entire volume and was followed in October by the appearance of TS Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land.

A first edition copy of James Joyce’s novel ‘Ulysses’ before being shown to Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge during a reception held by Irish Tanaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) Simon Coveney on 4 March 2020 in Dublin, Ireland. (Photo: Phil Noble / WPA Pool / Getty Images)

(Photo: Wikipedia)

The backdrop to these two literary monuments was the nihilism, anomie and social collapse in the aftermath of the death and destruction of World War 1, then known as the Great War. The pervasive mood of the time among all sections of society, but particularly the intellectual classes, was

memorably captured by Eliot in a critical essay he wrote on Ulysses, “Ulysses, Order and Myth”. Here he described the emotional, political and intellectual landscape of the time as “the immense panorama

of futility and anarchy that is contemporary history”.

In the essay, Eliot praised Joyce’s use of what he called the “mythic method” to give order and shape to the disintegration and fragmentation of the post-war world.

Depending on the reader’s tastes and criteria, Ulysses is a leading candidate for the greatest novel ever written. It is perhaps the prime embodiment of the observation of the literary critic and political theorist Georg Lukács: “The novel is the epic of a world that has been abandoned by God.”

In Ulysses, Joyce recasts Homer’s epic — describing Ulysses’s or, to use the Greek name, Odysseus’s journey across the Mediterranean after the Trojan War to return to his wife Penelope at his home Ithaca — in a modern, mundane and thoroughly unheroic setting.

In placing the hopelessness and purposelessness implicit in the legend of the Wandering Jew within the framework of Homer’s epic, the novel ironically and playfully subverts the grand pretensions of the epic, presenting a day in the life of an unexceptional and ordinary figure, a Jewish advertising salesman, Leopold Bloom.

While the subject matter of Joyce’s novel represents a descent from the grand and aristocratic values of a foundational narrative of Western culture to the everyday life of an ordinary man, Ulysses nevertheless displays undoubted epic ambition. The novel is a display of astonishing linguistic versatility and is highly complex in its structure. In one chapter Joyce depicts the evolution of English literature in a bravura performance parodying the literary styles of the various ages of English literature.

A long and challenging work, Ulysses repays the attention of the attentive and persistent reader insofar as its linguistic brilliance and dexterity resemble watching the greatest of gymnasts or trapeze artists performing the most elaborate, exacting and breathtaking routines.

circa 1933: English critic, novelist and essayist Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), circa 1933. (Photo: Central Press / Getty Images)

The content of Ulysses which attracted accusations of obscenity, leading to banning in many countries, and its often mockingly playful exhibitions of manipulations of language and verbal exhibitionism, was met with a mixture of outrage and misunderstanding. Virginia Woolf, herself a modernist novelist, dismissed the novel as “an illiterate, underbred book”, and Ulysses was banned for perceived obscenity in both England and the US.

The Waste Land: a modernist poetic masterpiece

Similarly, TS Eliot’s modernist poetic masterpiece, The Waste Land was met with varying degrees of incomprehension, ridicule and scorn among the cultural old guard. “A grunt would serve equally well,” was the notorious put-down of the poem by JC Squire, a prominent member of the English literary establishment. Nevertheless, the poem captured the imagination of the intellectual youth of the early 20th century, echoing the mood of despair, hopelessness and disenchantment of the post-World War 1 era.

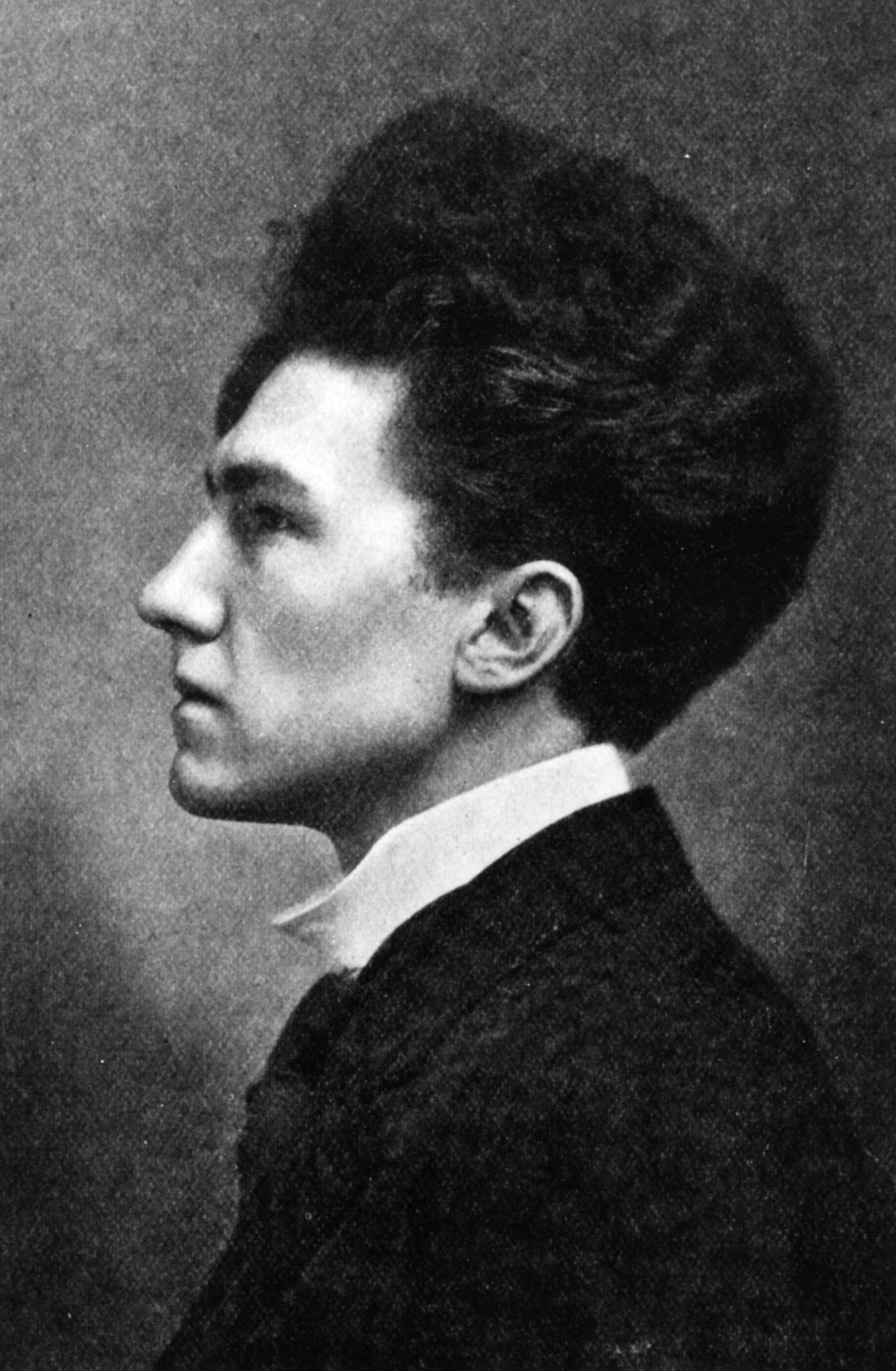

TS Eliot (1888-1965). Naturalised British in 1927, awarded a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948. (Photo: Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

Eliot composed The Waste Land after suffering a nervous breakdown caused by stress and overwork and the impact of his disastrous and impulsive marriage which he contracted, as an expatriate American philosophy student in England, to Englishwoman Vivienne Haigh-Wood. Despite his American origins, which 100 years ago was a cultural backwater, Eliot’s literary mentor, Ezra Pound, noted that Eliot had taught himself to be a cutting-edge modernist poet.

Circa 1910: Ezra Loomis Pound (1885-1972) American poet and composer. (Photo: Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

The Waste Land famously opens with a characteristically modernist ironic and iconoclastic subversion of the traditional poetic response to spring as a time of rebirth:

“April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.”

The Waste Land is a beguiling and frustrating poem as it has no obvious structure, presents kaleidoscopic changes in its points of view and settings, and is laden with literary allusions and enigmatic but haunting imagery. At times, the poem ascends to moments of pure musicality or what Eliot himself called “the music of poetry”, embodying the dictum of the 19th-century aesthete Walter Pater, that “All art aspires to the condition of music.”

It is always interesting to observe both ordinary readers and professional literary critics grappling with The Waste Land and their attempts to decipher it. The poem is both allusive and elusive, because its multiple points of view, fragmented structure and mysterious images lend themselves to multiple interpretations.

An early Frank Kermode, perhaps the greatest literary critic of the last century, wrote that “the poem resists an imposed order: it is part of its greatness”. His statement, later in the same essay, “to have Eliot’s great poem in one’s life involves an irrevocable but repeated act of love”, will surely strike a chord with all readers who have been captivated by The Waste Land.

Eliot himself was dismissive of interpretations of the poem which regarded it as an expression of the disillusionment of the post-war era. Commenting in old age on his failed marriage to Haigh-Wood, he stated: “To her the marriage brought no happiness… to me it brought the state of mind out of which came The Waste Land.”

As Eliot stated elsewhere, it was but “a personal and wholly insignificant grouse about life”.

Resonance with the epoch

Yet The Waste Land’s tremendous contemporary impact can only be understood by the manner in which it resonated with its epoch. Its fragmented forms re-enact the death and destruction of the Great War and the demolition of the enlightenment and 19th-century cult of progress with the catastrophic descent of Europe into slaughter.

The Great War and its historical moment are powerfully if subtly present in the poem. Its very title recalls the ravaged and disfigured landscape of the trenches. Its image of “hooded hordes swarming/ Over endless plains” evokes the mass movements of troops in the war and its reference to an archduke gesture towards the assassination which was the spark that ignited the war.

The poem also presents the degradation of the post-war world in its succession of broken and sordid images:

“I think we are in rat’s alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.”

Although arguably the bleakest major poem in the English language, The Waste Land also contains interludes of transcendent beauty and aesthetic rapture which form a counterpoint to the ugliness and squalor of much of its imagery:

“where the walls

Of Magnus Martyr hold

Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.”

Here the poem ascends to a state of verbal musicality, and art triumphantly asserts itself as something enduring, something that the walls still “hold”.

Such moments in The Waste Land imply the redemptive quality of art amid suffering and torment, be it that of the artist or the audience.

Eliot would not have entirely concurred with Friedrich Nietzsche’s bold declaration that “it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified”. Nevertheless, Eliot, who had reviewed Nietzsche as a philosophy student, would have agreed that great art and poetry can be a source of consolation.

Destined for an academic career in philosophy before devoting himself to poetry, Eliot was too sophisticated a thinker to make the exaggerated claims of such influential critics as Matthew Arnold and IA Richards, that, as a kind of substitute religion, “poetry could save us”.

Rather, in an essay published just more than a decade after The Waste Land, Eliot makes a more modest but still profound defence of poetry. He argued that in the face of the random and chaotic appearance of reality, a poem can provide the reader with a glimpse of the underlying unity of reality and thereby help the reader to be more at peace with the world.

For those who do not wish to plough through about 700 pages of Ulysses, the 433 lines of The Waste Land present a less-daunting prospect for the unfamiliar reader. If captivated by its haunting and evocative cadences, the reader will return repeatedly to the poem, which after 100 years still retains its ability to surprise, baffle, intrigue and console.

After the appearance of Ulysses and The Waste Land the novel and poetry were irrevocably changed. While the works were committed to representing life in all its harshness and drudgery, they did so in a way that displayed extraordinary verbal virtuosity and beauty, that leavened the unpalatable without avoiding or suppressing it. This is one of the gifts that “the aesthetic” can bestow on us. In a largely post-literate age, in a time when STEM subjects grab the largest slice of educational budgets, we could do worse than remind ourselves of the hugely humane and humanising benefits that these two great works offer us. At a time when human life requires — perhaps more than ever — a justification, we could do worse than to read or re-read these works. DM/MC/ML

Richard Mayer is a practising labour lawyer and athletics coach and holds various degrees including a MA on TS Eliot from Wits University.

Thank you for this inspiring and strangely moving article. The words “At a time when human existence – perhaps more than ever – requires justification…” struck me like a kick in the stomach. I know of persons close to me who have decided not to perpetuate human existence by refraining from having children precisely because of our times. While I respect their views, I am left with sadness. James’ Ulysses has been in my late mother’s (Marthina Jakoba “Sha” van Niekerk, née Swart) library for many years. I inherited it. She read it several times, but I abandoned it after a single measely attempt. I also inherited some of Eliot’s plays and poems, but not The Wasteland. However, I shall order it and take up your suggestion “to read or re-read these works.” I do think there are damn good reasons why these works are worthy of a centenarian mention. As for Nietzsche, I have been encountering him everywhere I read. Wish me luck!