BHEKISISA CENTRE FOR HEALTH JOURNALISM

Whatever happened to HIV/Aids activist Zackie Achmat?

Zackie Achmat’s voice was one of the loudest when it came to protesting against former president Thabo Mbeki’s Aids denialism in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He now lives in downtown Cape Town and fights State Capture — and broken trains.

Zackie Achmat asked if we could meet at Deluxe cafe in Cape Town’s Church Street. It’s an area in which he is often spotted walking his dog. The original plan had been to meet at his downtown apartment, but when asked for his address, Achmat had sent pictures of manicured lawns and statuary, all taken in the historic Company’s Garden.

Was this a wry comment from one of the founding members of Ndifuna Ukwazi (Dare to Know), which advocates affordable housing in well-located urban spaces? Friends who know Zackie said it would be consistent with his politics – and his sense of humour.

Arriving with Nawal, his dog, Zackie is wearing a breathable maroon running top and looks trim. His face remains youthful and will always look this way, I suspect, but his hair has silvered.

Jackie Achmat and his dog, Nawal, in front of Deluxe cafe in Church Street, Cape Town. (Photo: Jay Caboz)

“She tends to bark when strangers enter the home, so I thought let’s rather meet somewhere neutral first,” says Zackie, giving the dog a pat.

Zackie and Nawal — a Qur’anic name meaning “gift” — are met by Zuki Vuka, an organiser for the civil society coalition #UniteBehind, who sits with Zackie at the end of Deluxe cafe’s bar, going over the strategy for the afternoon’s public protest against the collapse of South Africa’s railways.

“There’s a miniature train on the Mouille Point promenade, and we [#UniteBehind and the African Climate Alliance] are going to be handing over a certificate of achievement to the Blue Train Park for having the only working train in South Africa,” says Zackie, who is set to receive the certificate himself, wearing a mask bearing the face of Transport Minister Fikile Mbalula.

#UniteBehind: Zackie Achmat at the Blue Train Park in Mouille Point protesting against the country’s broken trains. (Photo: Sean Christie)

It’s yet another subversive stunt from the man who, in 2002, smuggled Brazilian-made generic antiretrovirals into the country to protest the government’s Aids denialist policies, and then invited the media to meet him at Cape Town International Airport.

In 1998, Zackie and a handful of others had launched what would rapidly become one of the most prominent HIV/Aids advocacy movements in the world, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC). He had already been an activist for over two decades by that point, starting in 1976 when he helped set fire to his school during the student uprising.

But in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, Zackie applied his activist skills to fighting for access to HIV treatment and became one of the loudest voices against former president Thabo Mbeki’s Aids denialism.

Mbeki denied (and still does) that HIV causes Aids, and, as a result, refused to authorise policies that made treatment in the form of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) available in the public health sector.

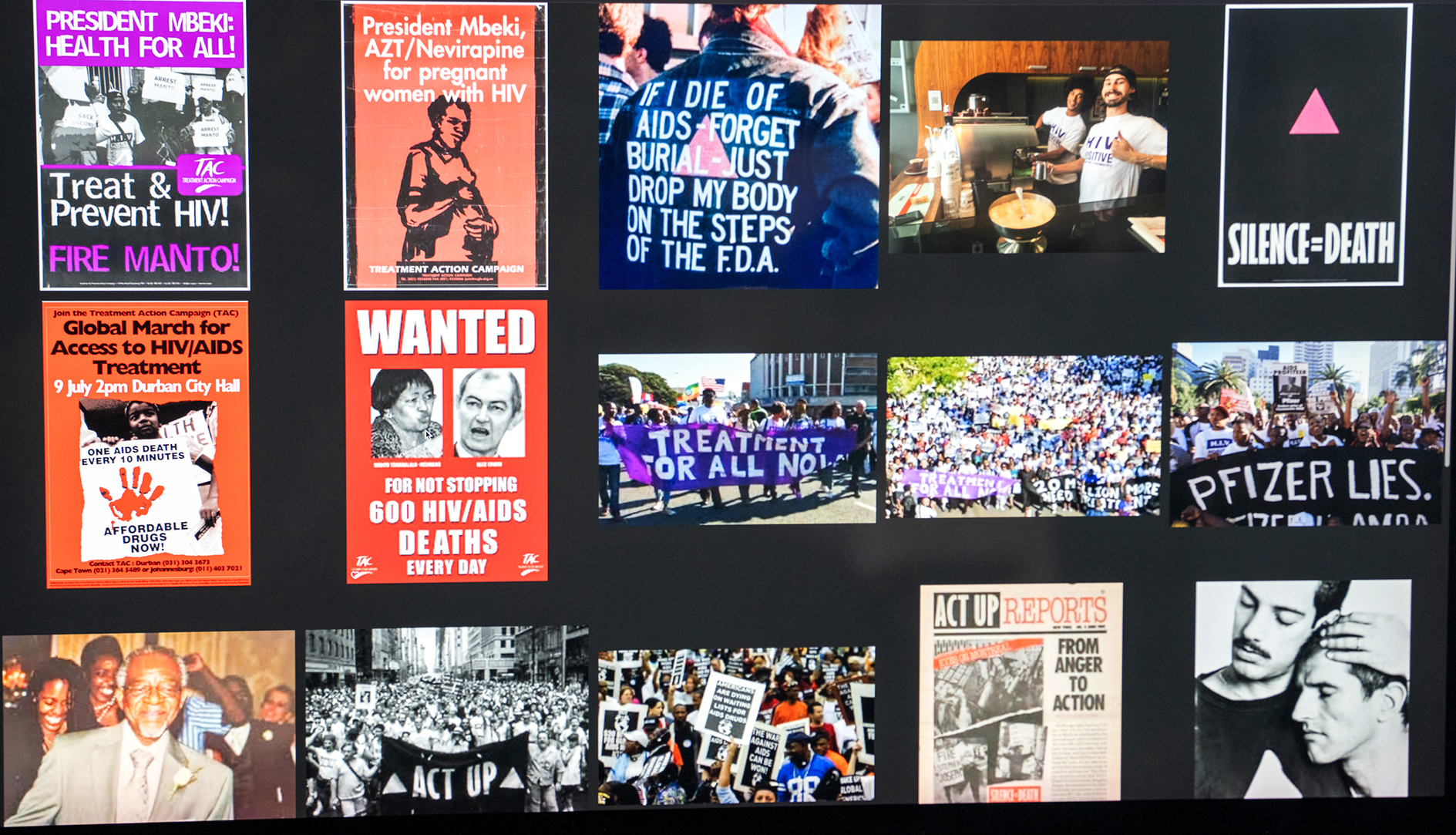

Treatment for All: Zackie Achmat is one of the founders of the Treatment Action Campaign that became famous for its sharp slogans. (Photo: Jay Caboz)

Zackie, who publicly declared his HIV status in 1998, became known for refusing to take ARVs obtained from the private sector until the state made the drugs available to everyone for free.

It took a visit from former president Nelson Mandela in 2002 – where Zackie asked Mandela to confront Mbeki about his policies – to get Zackie to take ARVs.

Zackie and his fellow activists finally took the government to the country’s highest court in 2002, when the state was ordered to provide all HIV-positive pregnant women with a drug that prevents mothers from transmitting the disease to their babies.

Free ARVs finally became available at state facilities in 2004.

From no treatment to 10 pills a day

Zackie is arguably his generation’s most prominent social justice advocate, although he has been less visible in recent years.

“Don’t be deceived … I’m at work,” Zackie smiles.

He is mostly focused on State Capture at the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (Prasa), and says he has read “over 100,000 pages of reports in the last few years, detailing how corruption and incompetence at the parastatal has caused the destruction of the rail lines, including the theft of 500 coaches a year, if you can believe that”.

We head for his home. It’s a fine September morning and Cape Town’s car-free boulevards are busy with pedestrians and hawkers. A woman, sitting with her legs out in front of her, sings gospel refrains in a strong tenor voice.

“I love walking the city centre — we’ve already walked 8 kilometres today,” says Zackie, stopping suddenly to take out his cellphone.

“Look at this.” It’s a message from Graeme Meintjies (deputy head of the University of Cape Town’s health faculty’s department of medicine), Zackie’s heart doctor, giving positive feedback following recent tests and commending Zackie’s regime of daily walks.

Downtown: Zackie Achmat lives in Cape Town’s city centre and takes daily walks with his dog, Nawal. (Photo: Jay Caboz)

Zackie’s health has been a matter of public interest since he declared his HIV-positive status two decades ago. Today, managing his HIV infection is simple and routine.

“I take seven pills in the morning and three at night. Watching my cholesterol after my 2005 heart attack is harder work, and the most difficult thing to manage by far is my depression,” Zackie says, his face unexpectedly breaking into a smile when he recognises a man walking towards him. They hug, and after a short chat, hug again and go their separate ways.

“We worked together at the Labia Theatre on Orange Street many years ago,” Zackie says. “He was the longest-serving projectionist. His wife was the cashier. I was an usher. I’m not sure if he and his wife stayed together, but he just informed me that she died recently.”

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Transforming Aids conferences

Zackie lives in an open-plan apartment in a building “surrounded by bloody Clicks pharmacies”. The door is open and two colleagues are at work at a large table in the kitchen area. The bed is unmade — Nawal quickly takes her place on it.

“They told me to tidy up,” Zackie says, pushing aside a stack of papers on the table and exposing two Salman Rushdie novels. Possibly triggered by the memory of the recent stabbing of Rushdie (by a 24-year-old who had at best read a few paragraphs of Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses), Zackie says, “We’ve lost sight of the bigger picture, you know.”

We? “Non-governmental organisations, movements. Ask any organisation working in South Africa today, why is Ukraine critical for us and for everyone? Some might say, because it pushes up the price of food, and it’s important to understand supply chains and all of that, but the most important thing is missed – the possibility of our extinction.”

Coffee conversations: ‘We’ve already merged HIV and TB care in clinics and hospitals, yet here in South Africa we have separate conferences for each disease,’ says Zackie Achmat. (Photo: Jay Caboz)

Zackie’s analysis of how local movements became inward-looking and ineffectual is multifaceted, and he sets it out with the easy erudition of someone who has spent a lot of time thinking and writing about such things.

He begins with healthcare, and what he sees as “the failure of the miniscule amount of activists that we have working in health” to understand the Covid pandemic as a harbinger of a new normal — “a condition where emergencies such as pandemics and climate change disasters are not exotic happenings, but things occurring at home on an ongoing basis, requiring a complete reorientation of emergency healthcare and a corresponding reorientation of activism”.

Zackie believes the biennial International Aids Conference should be transformed into an infectious diseases and emergencies conference, and that the infectious diseases bodies need to merge with the HIV organisations.

“The separation is no longer sustainable or tenable. We’ve already merged HIV and TB care in clinics and hospitals, yet here in South Africa we have separate conferences for each disease. It’s hubristic and a waste of money.”

Non-profit funding creates class differences

Perhaps anticipating the obvious follow-on question — where did South Africa’s movements lose the path? — Zackie begins paging through a thick file of TAC documents.

“Here it is,” he says, unclipping a copy of minutes from an early TAC Western Cape branch meeting: “Financial report,” he reads. “We received R2,500 from Johannesburg. We received R320 in cheque donations. We received R200 in cash donations. Students contributed R300. We have about R1,400 left for volunteers and the demonstration.

“That’s it … that’s how we were operating then,” Zackie says, explaining that the TAC’s total budget in 1998 was R15,000. In the second year, it was R200,000 and, by 2007, the organisation was spending R30-million a year.

“Funding undermines organisations,” he argues, and his colleagues smile knowingly — a familiar hobby horse is being mounted.

“It turns us activists into bureaucrats, and I use the word ‘us’ because I wasn’t excluded from that process. It pushes up salaries, creating a class of people who are different in status from their comrades and communities that they organise, leading to an inevitable conflict.”

The alternative funding model he has in mind hearkens back to the approach of the Marxist Workers Tendency of the African National Congress, which Achmat and other early TAC leaders belonged to.

“In the Tendency, members were the ones who contributed. If you earned over R10,000 a month, you had to give a third of your salary. Over R20,000, and it was 50%.”

Aerial view: ‘Go anywhere in the world, and you see that working-class children don’t have the knowledge of how a computer works, or any sense of the cultural inheritance of the world,’ says Zackie Achmat. (Photo: Jay Caboz)

The second part of his proposed funding model envisages trade unions giving a percentage of the dividends they get from their investments to movements.

“The unions have an enormous amount of money, and if they do this, they will spend more than all the donors in the country, including the overseas donors. Similarly, if the churches and mosques gave 5% of their income for food security work, or for creating jobs for renewable energy and stuff like that, we’ll flip the model entirely. It would mean the public would contribute.”

These ideas aren’t new, but the idiom in which Zackie communicates them — outraged without being shrill, irreverent without slipping into poor taste — compels attention. When he starts talking about how progressive political space has been captured by the middle and upper classes, I don’t want to miss a word.

His biggest concern, he says, is what he terms “the dispossession of working-class children of knowledge that is social property”.

“Go anywhere in the world, and you see that working-class children don’t have the knowledge of how a computer works, or any sense of the cultural inheritance of the world.

“In our country, slavery, colonialism and apartheid have added different and dangerous layers of dispossession, and we aren’t addressing it.

“From our universities we tweet, Facebook and TikTok in what the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley called a wilful exaggeration of our own despair, and that undermines the possibility — not the possibility, the damn necessity — of creating movements that include everyone we can possibly get into them.”

The persisting trauma of fighting HIV denialism

Zackie folds and refolds one of Nawal’s poo bags. He sees me watching this performance and puts the bag down, relaxing his voice.

“I’m just so grateful that we didn’t have all of that shite [social media] during the Aids fight, because the battle against the HIV denialists would have been a thousand times worse. You would have had Thabo Mbeki’s acolytes — the Ronald Suresh Roberts’, not to mention the San Francisco mad ones — trolling one’s every utterance. It would have been a nightmare.”

There is another problem, “quite close to home — close to the bone”, but before he gets into it, Zackie asks his colleagues for the room. They duly close their laptops, pack their things and leave. Nawal sees them out with a few proprietary barks.

“Something we have not recognised and dealt with in our country in relation to HIV is the post-traumatic stress disorder among activists who dealt with death on a daily basis.

“It was a war without bullets — the government had declared civil war on its own people,” he says, adding quietly that he did not speak about HIV for almost 15 years, and found he couldn’t wear his HIV-positive T-shirt because it felt as if the phrase had been burnt into his body.

War without bullets: Zackie Achmat says HIV activists who fought HIV denialism are still traumatised because they dealt with death daily. (Photo: Jay Caboz)

“I was going through a really bad depression in the early days of the TAC and I hadn’t seen a psychiatrist or anything, so my doctor at the time started insisting that I write down my dreams, and I did,” says Zackie, dream journal in hand.

He begins to read his decades-old, looping handwriting. The narrative relates to a friend of his sister, “a gay man, who was carried to the grave by lesbians, because his own family shunned him even in death”.

The dream goes on, but Zackie stops and says, “When I read it now, I realise that in the unconscious of every activist and every person with HIV, this was going on, and as a result so many of us left the movement, and the institutional memory of that time effectively dispersed.

“What people remember today is what we want to remember. Nobody is interested in meticulously researching what it actually took to build a community-based organisation that was also an international organisation.”

Zackie says he is only now recovering, and he talks and moves like a person lightened from heavy burdens. Our conversation has run on, and the Prasa protest is almost upon him. He picks up a printout of the transport minister’s face and smiles mischievously.

“I still have to cut out the eyes.” DM/MC

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.

A beautiful man.