TAPPED OUT

SA is ‘staring down the barrel’ of a water security crisis predicted decades ago – expert

Amid ongoing restrictions in Gauteng, experts have highlighted that water security in the whole of South Africa is under threat — a fact that has been known for the past two decades.

“We are staring down the barrel,” said Professor Anthony Turton, a water resource management specialist at the University of Free State, at a public engagement on 26 October with Joburg residents and water specialists about the ongoing water crisis in Gauteng.

This is despite Rand Water CEO Sipho Mosai emphasising at a media briefing recently that there is more than enough water going into the system.

The City of Joburg and Rand Water have been at pains to say that the recent water shortages in parts of Gauteng were initially caused by power failures (not scheduled load shedding) at two of Rand Water’s purification plants in Vereeniging in late September and then exacerbated by scheduled rolling blackouts.

Simon Xaba, the general manager of operations at Rand Water, told Daily Maverick: “It is my opinion that if you have this frequent load shedding, you are technically fiddling with the stability of power.”

But while power plays an integral role in getting water pumped into reservoirs, Turton emphasised that experts in the water sector had known for the last two decades that South Africa would face a water deficit in the future.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Water, water, nowhere and precious little to drink”

They predicted in 2002 that by 2025 South Africa would need 63 billion cubic metres to service demand for the country despite only having 38 billion cubic metres of water accessible in dams.

Turton, the former vice-chair of the research advisory panel for the National Water Resource Strategy (NWRS) at the CSIR, explained to Daily Maverick that the first NWRS — which was published in 2004, but the technical team had been workshopping the data since 2002 — is the most definitive study of the balance between water demand and supply South Africa has seen. At the time, the technical team quantified the country’s total water volume at 53 billion cubic metres.

The 2004 NWRS stated: “If we look forward to the year 2025, even if we factor in further infrastructure development, we find that several additional water management areas will most likely be in a situation of water deficit.”

There have been two NWRSes since, one in 2013 and one that came out this year, which is still under public review. Both used the same data as the first report.

Since then, independent peer-reviewed studies have used sophisticated mathematical modelling to revise SA’s total water volume from 53 billion cubic metres to 48 billion cubic metres. Turton explained that the number is lower in part because of climate change and the more sophisticated modelling system.

However, the accessible water in South Africa’s dams amounts to just 38 billion cubic metres.

This is because we can’t use water that is known in legal terms as the reserve. The reserve consists of two components: water in reserve needed for basic human needs, which is 25 litres per person per day that has to be left in the river if there is no piped water available in that area; and the ecological reserve, which is needed to sustain the ecological functionality of the ecosystem.

So, assuming that the dams are full and that no storage capacity has been lost to sediment, South Africa has access to 38 billion cubic metres of water. But we need 63 billion cubic metres of water to service demand by 2025.

Even in 2008, WWF South Africa warned that 98% of available water resources was already fully used and the country could run out of water by 2025.

“This doesn’t mean the taps will run dry, but that water-intensive industries won’t be able to continue working as before and there may be water rationing,” said the chief executive of WWF South Africa, Morné du Plessis, in a media briefing in 2008.

“What we’re saying about water today [in 2008] is what the energy people were saying to the government 10 years ago,” Du Plessis said.

Etienne Hugo, general manager of operations at Johannesburg Water, speaking at a public meeting on the Joburg water crisis at Marks Park Sports Club, Emmarentia, Johannesburg, 28 October 2022. (Photo: Julia Evans)

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

What does running out of water actually mean?

We’ve technically already run out of water.

Even though dams are full right now — the Vaal Dam is at 92% capacity — we’ve run out of water that is allowed to be allocated.

“When we say we ran out of water, we mean we have run out of water to allocate, that the demand for the licences for that water exceeds the available supply,” explained Turton.

In 2002, the technical team working on the first NWRS said that 98% of the total volume available in SA’s 19 water management areas had already been allocated.

“We’ve given authorisations for water — for paper and pulp mills and oil refineries, etc — they’re all got their allocation of water, and then we’ve allocated more water than we have available,” said Turton.

He explained that the allocation, known as ELU (existing lawful use), goes to lawful users of water as defined by the National Water Act.

“The sum of those ELU allocations equalled 98% of the known supply, with some water management areas being over-allocated by 120%,” said Turton.

The first NWRS broke down SA’s water allocation to 62% for agricultural irrigation, 27% for domestic and urban requirements, 8% for mining, large industries and power generation, and 3% for commercial forestry plantations.

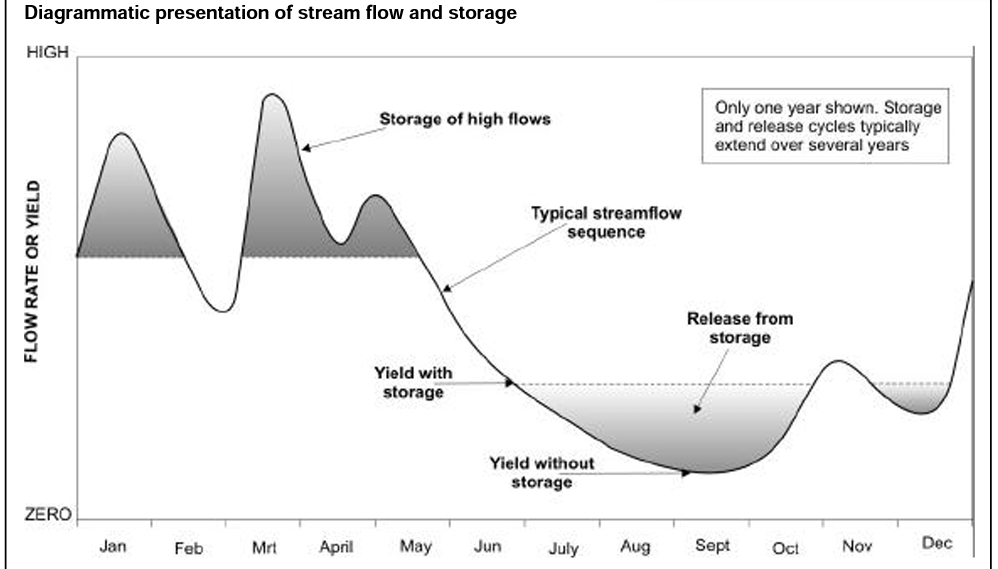

“The reason why the [Vaal] dam is full is because we’ve got to keep it for the years when we don’t have water — for the dry years,” explained Turton.

“We work on long-term averages and long-term trends. And the long-term trend was we ran out of water in 2002.”

As explained in the first NWRS, the “total water available includes the total local yield plus water transferred from elsewhere”.

Turton said technical specialists in the water sector had known about this for 20 years but had been ignored.

Government needs to step up

Dr Ferial Adam, manager of the civil action organisation WaterCAN, emphasised at the public meeting on 26 October that the problem lies in poor planning, failing infrastructure, underspending and sewage pollution.

According to the Department of Water and Sanitation’s 2022 Blue Drop Report, 52% of SA’s water supply systems are in the medium to critical risk groups, 60% don’t comply with microbiological standards and 77% don’t comply with chemical standards.

The 2022 Green Drop Report classified about 60% of SA’s wastewater treatment works as being in a “poor to critical” state, and only 23 out of 995 wastewater systems qualified for Green Drop certification.

At its recent media briefing, Rand Water emphasised that South Africa, and Gauteng specifically, has high water consumption rates compared with the rest of the world, and while imploring the media not to make it seem that it was blaming consumers, encouraged a culture of conservation.

Dr Ferial Adam, manager at WaterCAN, speaking at a public meeting on the Joburg water crisis at Marks Park Sports Club, Emmarentia, Johannesburg, 28 October 2022. (Photo: Julia Evans)

Read more in Daily Maverick: “Water crisis? Recent cuts are due to an unstable electrical system, not lack of supply”

Rand Water reported that water consumption in South Africa is 233 litres per capita per day, which is relatively high compared with the world average of 173 per capita per day.

And in Gauteng, 305 litres per capita per day is consumed during peak demand times.

However, Adam said Rand Water had failed to emphasise that this high consumption is because of extreme water losses — the last available Rand Water data indicates that 40% of water is lost due to leakages.

So, out of the 4,900 megalitres that Rand Water supplies every day, almost 2,000 megalitres are lost because of leaking pipes and ageing infrastructure.

Turton agreed that the consumption numbers Rand Water supplied were misleading — breaking down the numbers as such:

If Rand Water pumps 4,900 million litres to 17 million people, and 40% is lost to water leaks and 10% is allocated to commercial users, it’s actually 160 litres per person per day, which is below the global average and far below the estimated Gauteng consumption.

The 2019 National Water and Sanitation Master Plan reported that municipalities were losing about 1,660 million cubic metres of water per year.

As water costs R6 per cubic metre, this amounts to R9.9-billion lost annually.

Adam emphasised that only 46% of South Africans have a tap in their home and the government needs to step up, because we are “pumping water into an empty bucket”.

Solution

Turton said that even though it might seem that the situation is dire, there is a solution.

He emphasised that water is an infinitely renewable resource, and as a renewable source. “All we have to do is recycle our total national water resource 1.6 times, and then we won’t have a water crisis any more. In fact, we can then have full employment.”

We need to multiply the 38 billion cubic metres that are available in the dams by 1.6 to meet the upcoming demand of 63 billion cubic metres, which can be done by recycling the country’s total water resources.

However, to do that, we need policy certainty for the recovery, reuse and recycling of water — and at the moment we don’t have that policy.

Turton said that because we don’t have this policy, “we don’t have an enabling environment for capital and technology to come into the space”.

“If we had to have a policy that accepts that water is an infinitely renewable resource, we would see targets being set. And so, for example, if you were to set a target that over the next 20 years we have to recycle our water source 1.6 times, but you start off with a smaller target and then ramp up over time to this bigger target.”

Turton explained that at the moment all of our water is treated to South African National Standard (Sans) 241.

“Whether you flush your toilet with it, whether you wash your car with it, whether you cool down your industrial process plant with it, whether you irrigate your garden with it, whether you drink it, it’s all the same standard water.

“Now, that doesn’t make sense,” he said.

So, we need a policy change, which has to come from the government.

Turton added that we can recover water from sewage — SA produces five billion litres of sewage every day — and that water can be recovered, not as drinking water, but recycled back to non-drinking uses like cooling down boilers or irrigating public gardens.

Turton said we should also implement a “dual-stream reticulation economy”, which means having two pipes for every end user — one that supplies standardised drinking water and one that provides grey water.

“So, it will be safe to use, but it’s not drinking water. And that’s what you flush your toilet with, that’s what you want to water the garden with,” explained Turton.

Turton emphasised that all water supplied by entities like Rand Water or Umgeni Water is Sans 241 standard, but only 1% of that is for drinking.

Turton suggests that instead, we treat 1% to the highest standard, but then we treat the rest to a standard that is safe, but not necessarily a drinking standard.

“That’s the direction we should go in,” said Turton. “And, at the moment, there’s just no insight into this possibility by any government leader. They keep on following the same old pattern of just building another dam and just blaming the public.” DM/OBP

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Prof Turton is right about 2 things:

* We can and should recycle our water far more. However, cadre deployment and corruption has meant only 2% of Waste Water Works meant the required standard.

* It’s wasteful to treat all water, for whatever purpose, to the same very high standard as drinking water.

Where I differ is in his saying that sewage water can’t / shouldn’t be polished to drinking water standard. It’s perfectly feasible provided systems are well designed and run by competent people. It was said decades ago that London water is recycled 7 times, and their tap water is quite drinkable.

The issue here is an ANC that has produced volumes of documents on “policy” for almost everything and that put out document that proclaimed that it is “Ready to Govern”, however, the experience as admitted by its own Kgalema Motlanthe the ANC was never ready to govern but to ” misgovern”. There is no water problem in South Africa but an ANC problem. You have ANC government Ministers strutting like peacocks so that everybody can see them in climate change conferences. In these conferences are delegates from desert countries who do not moan about water problems because they use desalination technology properly. You even have countries that face drought like us including Australia dealing with the issue instead of the hogwash day zero paraded even by the DA. California in the face of drought, built dams with desalinated water. The other two issues related to the ANC problem is the exploitation of drought for purposes of corruption or sabotage of water pumping stations for water trucks to continue delivering water and filling pockets of ANC people who fund campaigns of individuals on the ground. Any person with a coefficient of thinking on the urban water infrastructure would have known that urbanisation as a result of influx control would put pressure on the infrastructure designed for the few. This goes for pipelines and pumping stations. The ANC failed to address this with incompetent officials employed to facilitate stealing public money.

Well said Cunningham. The ANC have been neglecting the upgrading of infrastructure for decades, and it is now starting to overhaul them. The railway system . . . the electrical infrastructure . . . the sanitation plants . . . the post office . . . everything.

100 % on the issue of not treating ALL water to SANS 241 standards. The big problem with SANS 241 is that it is not achievable in many rural scenarios especially where groundwater forms the source of supply, eg rural schools, small towns. Its not just the big cities were the problem lies ito existing and future water deficits. Many small towns rely on groundwater (GW) as their supply source. Urbanization to these small towns (both surface and GW supplied) is too high in relation to the rate of investment in new water resources, treatment ability and waste water treatment. Conjunctive supply using all available resources, including re-treatment, is the only way to go. Re-treatment on a small scale can be costly though. What is missing from this whole debate is the need to also manage population growth and the rate of urbanization which is exceeding the carrying capacity of the towns and cities. There is insufficient capital available to meet the required speed of infrastructure upgrade to satisfy the urbanization rate. Municipalities when expanding their groundwater resources need to look beyond their urban edge and not treat groundwater as an interim or emergency supply – it forms an integral part of a conjunctive supply scheme.

Ritchie, the important part of the solution given in the article is that the SANS241 is only needed for 1% of all water. And there is no reason why that can’t be achievable. Besides, our Constitutional values set certain standards that have to be met, for instance the right to a healthy environment. So it is true that, in those far-off rural villages, far more than 1% of water must be of drinking standard; say 20% as a thumbsuck percentage. Then that municipality should put the cost of proper water treatment for meeting that standard on the Integral Development Plan, and national government should both fund and provide the expertise to have it done. It is time we as South Africans start demanding proper government – that is all that is needed. If we did from 1994, Zuma and his Gupta friend would probably never even had a chance to loot. Take note, the fact that the Constitution sets these standards means that it is a moral responsibility – it has to be met, even if taxes have to be raised in order to ensure that we all are able to live a decent life. But I don’t believe that it would be needed. All that needs to be done is, as dr. Adam and many of the respondents on this page says “PROPER PLANNING”.

Dr Adam put her finger on it. “Poor planning.” Would some clever person calculate the totally roof area of the homes, businesses, factories in SA, multiply by the rain falling on those rooves. How many billion cubes does it come to?

Sigh, so boring, so simple. “South Africa has access to 38 billion cubic metres of water.” Absolute baloney, far more falls on our rooves and we haven’t even started on the most abundant source of pristine, unpolluted water in SA. The rain!

The rain falling on a roof in an average wet season month will supply that home for a whole year, but only if we harvest and can store it.

Build an underground reservoir, 5m in diameter, 2m deep, plaster and roof it, and bingo, problem solved. Approximate cost R30,000, needs to be updated perhaps.

This is not theory. We’ve done it, and used municipal water for only two months in ten years.

Where is the “boer sal een plan maak” that we boast so much about? Where is the lateral thinking of water engineers and planners.

Really, there’s a simple, simple, simple solution. We learned how to do it whilst living in the Netherlands. Their favourite saying is “die wat niet wil horen moet voelen.” Those who will not hear must feel. And so it.

I have no sympathy whatsoever except for the very poor. Spend R30,000 and have pristine free water for ever. Nothing could be simpler.

Do it or feel the pain.

So, time for the government to step up, local, provincial and national. They should already have since 20 years ago. I especially liked the proposal of two pipes per stand, one for grey water and one for drinkable water. As far as I can remember, this is how the Sasol plant in Secunda have been operating since it was built in the 1970’s. So what is wrong with the SA government? Certainly they can do better than they are doing?