My story

In search of the true story about CJ Langenhoven and my great-grandfather

Ou Tin’s father — Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk — had been a teacher on a farm school in the Hoeko Valley where one of his pupils was an impressionable young boy who’d go on to make a name for himself as a writer.

My maternal grandparents were relatively poor, spoke Afrikaans and lived in a rented house in Great Brak River where at 6 o’clock every morning, Ouma fired up the coal stove so she could bake bread in the oven. After a fried breakfast, Oupa stood in front of the wardrobe mirror, fastened his waistcoat over his considerable girth, straightened his tie, perfunctorily brushed the lapels of his brown, double-breasted pinstriped suit, put on his fedora at a rakish angle and went out through the garden gate to the wood-and-iron garage on the street. He wheeled out his backpedal-brake Humber, put on his trouser clips and set off along the untarred Station Road for the power station where he was employed as an electrician.

His bachelor brother-in-law lived with them and also cycled to work wearing a suit and tie, but he had a racing bike with dropped handlebars and nine-speed gears. He worked as a nurseryman for the affluent Searle family who, it seemed, owned almost everything in Great Brak River — including the filling station, the general store, the power station, Dr Watson shoe factory and Oupa and Ouma’s home. In the village, my great-uncle was known as Ou Tin, but his full name was Marthinus Paulus Dawid Joost Bloemkolk.

Ou Tin’s father — Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk — had been a teacher on a farm school in the Hoeko Valley where one of his pupils was an impressionable young boy who’d go on to make a name for himself as a writer. In his autobiography, CJ Langenhoven singled out Meester Bloemkolk and acknowledged the formative influence he’d had on him. “He was pure gold, an upright, noble man and a Christian in all he said and did.”

This was Mum’s family’s one and only claim to fame.

***

When I was first told about the praise that had been showered on my great-grandfather, I had no idea who Langenhoven was or that he’d written a poem that, once set to music, would eventually be adopted as the country’s national anthem. That’s just as well because at the age of eleven I rejected what I imagined “Die Stem” stood for, refused to sing it at school and would have felt highly conflicted about my illustrious forebear’s association with the likes of Langenhoven.

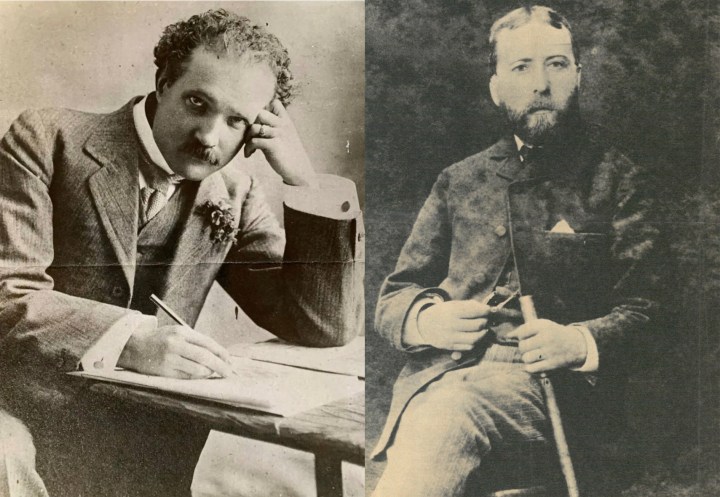

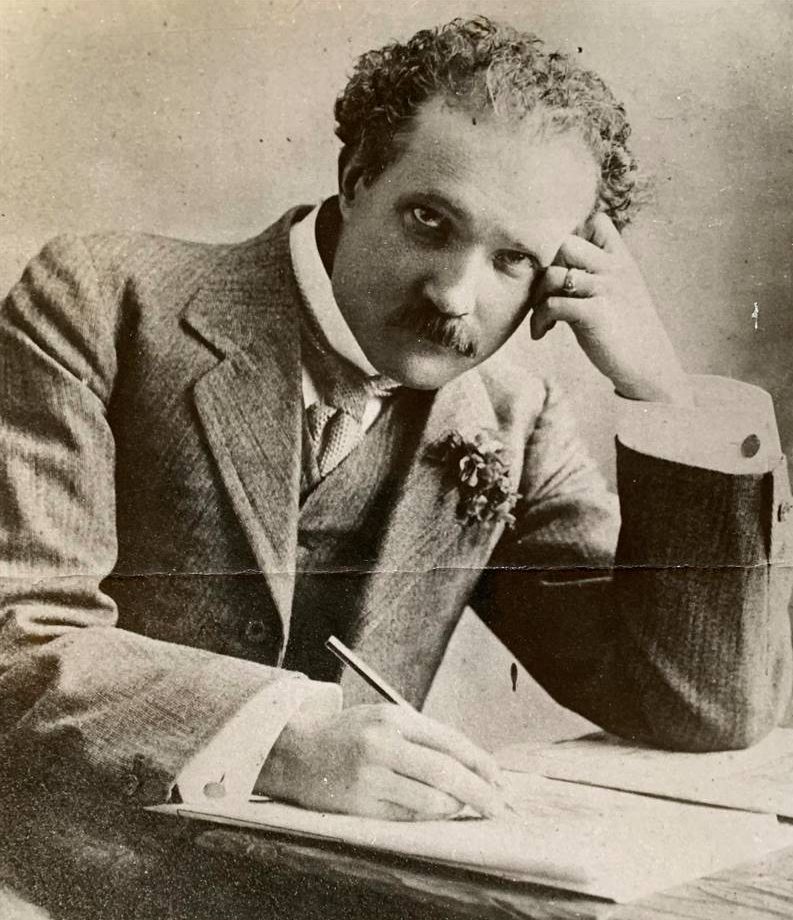

Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk shortly after his arrival in the Hoeko Valley. Image: Supplied by the author

Ouma and Oupa’s dining room was gloomy and sparsely decorated with black-and-white photos framed behind glass. One of those photos was a studio portrait of Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk. He’s wearing what Langenhoven described as his “smart and fashionable” clothing and is staring into the lens with a mildly desolate expression. He died when Ouma was ten and never knew any of her eight children who’d once sat at the long dining room table.

Langenhoven died in 1932, the year U dienswillige dienaar (Your Willing Servant) was published. In Chapter 10 he wrote that “Bible study, translation work and writing essays in English and Dutch under Bloemkolk’s supervision were predominant influences that helped shape the quality of my work as a writer.” Of course, my great-grandfather had no inkling that the little boy nicknamed Petiet would one day grow up to be a renowned author and that he was already playing a formative role in his development. Langenhoven described him as a “refined gentleman”, although he added that he “was not highly educated and had no training as a teacher.”

There’s another story that was put about by Langenhoven — and it’s one to which the Bloemkolk descendants seemed to attach greater importance. “Although he didn’t talk much about himself,” he wrote, “we gathered he was the son of a rich man whose prospects were dashed when disaster struck.” Over the years, the story obviously became embellished and Mum was fond of telling me that, although she grew up poor, her grandfather was in all likelihood descended from the Dutch aristocracy.

Poet and Author CJ Langenhoven. Image: Brümmer Archive

***

To commemorate Langenhoven’s centenary in 1973, Die Huisgenoot published an article by Retief Koch under the heading, “Langenhoven Immortalised Their Father”. Along with the studio portrait of Meester Bloemkolk that occupied pride of place in Ouma and Oupa’s dining room, there were photos of my great-grandfather’s three surviving children — Ouma, the former primary school teacher Hatie Meyer and a colour photo of Ou Tin holding an orchid. The caption under Ou Tin’s photo reads, “Probably the only Bloemkolk in South Africa.”

I was at theatre school in Bristol when this article appeared. Mum posted it to me but at that stage, I wasn’t overly interested. A few years later I relocated to Amsterdam and started to wonder about my Dutch great-grandfather. I soon discovered that if Ou Tin was the only remaining Bloemkolk in South Africa, they were also thin on the ground in Holland. I’d heard of a Fritz Bloemkolk, who was financial administrator of a theatre in Arnhem, but I never met him nor any other Bloemkolk during the two decades I lived there.

When my parents visited Amsterdam, I questioned Mum about our aristocratic ancestor. Where had he lived before going to South Africa? Nobody in the family knew the answer to that question. The poor might take pride in thinking they were descended from the good and the great but, when push comes to shove, putting bread on the table is more important than tracing their ancestry. When I pressed her, Mum became rather vague and said she thought he might have come from “somewhere in the south”, although she couldn’t be more specific. If he really was an aristocrat, I said warming to my theme, there must have been a family tree. But if there ever was proof of his noble lineage, Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk must have lost it along with the family fortune.

***

Apart from his status as a footnote in Afrikaans literature, there’s very little else we know about my Dutch great-grandfather. Did he have brothers and sisters? Was he really the son of a rich man who’d lost a fortune? What made him choose to come to South Africa? Retief Koch mentions he’d suffered from a chest condition, which was something new to me. Perhaps he had consumption and — like many Victorians from the 1870s onwards — came to the Karoo because there was a general belief in the beneficial effects of high altitude and dry air.

We know he disembarked in Cape Town in 1880 and taught at a farm school in Anysberg in the Montagu district. In 1883, he took up a teaching post in the Hoeko Valley where, before his arrival, Langenhoven’s foster father converted an abandoned blacksmith’s workshop into a temporary schoolhouse. That’s where the ten-year-old Langenhoven encountered his first teacher.

For over three years, Bloemkolk boarded with Langenhoven’s foster parents, “and in all that time, whether in word or deed, there was nothing with which he could have been reproached.” He was a bachelor but, according to Retief Koch, he’d left his heart behind in Holland with a young lady called Agatha Hendrika Negryn. I imagined him sitting at a rough-hewn table in the guestroom, dipping a steel nib into an inkwell and framing his marriage proposal.

In 1885, they were married by proxy in the Netherlands. Dutch law made provision — and still does — for a marriage to take place without the groom being present, as long as he sent a glove to represent him and someone deputised as his proxy in a civil ceremony. (This practice was more commonly referred to as met de handschoen getrouwd — married with the glove.) The following year, Agatha undertook the journey to South Africa, secure in the knowledge that she was a married woman. Their six children were born in the Hoeko Valley and their proverbial Dutch frugality ensured they came out on his meagre salary.

By 1904, my great-grandfather’s chest condition had worsened and, rather incomprehensibly, a doctor recommended a coastal climate. Acting on this advice, the family moved to Great Brak River and Meester Bloemkolk took up a post at the new school established by the Searle family. He died the following year at the age of 51. This necessitated his oldest son, Paul, leaving school at the age of 14 and going to work in the Dr Watson shoe factory. Seven years later, Agatha was laid to rest next to her husband and the 17-year-old Marietjie — my future Ouma — assumed the responsibility of running the home.

***

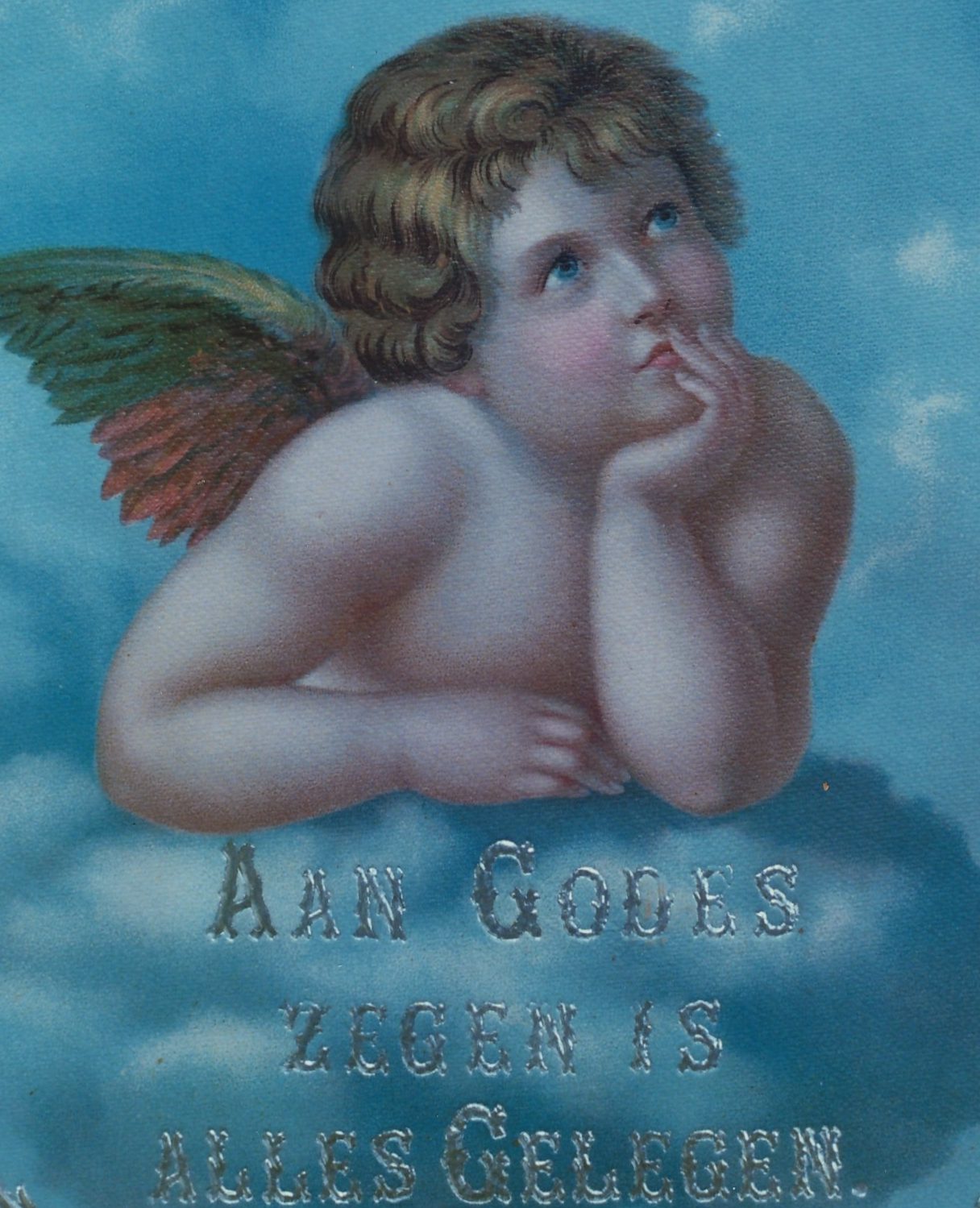

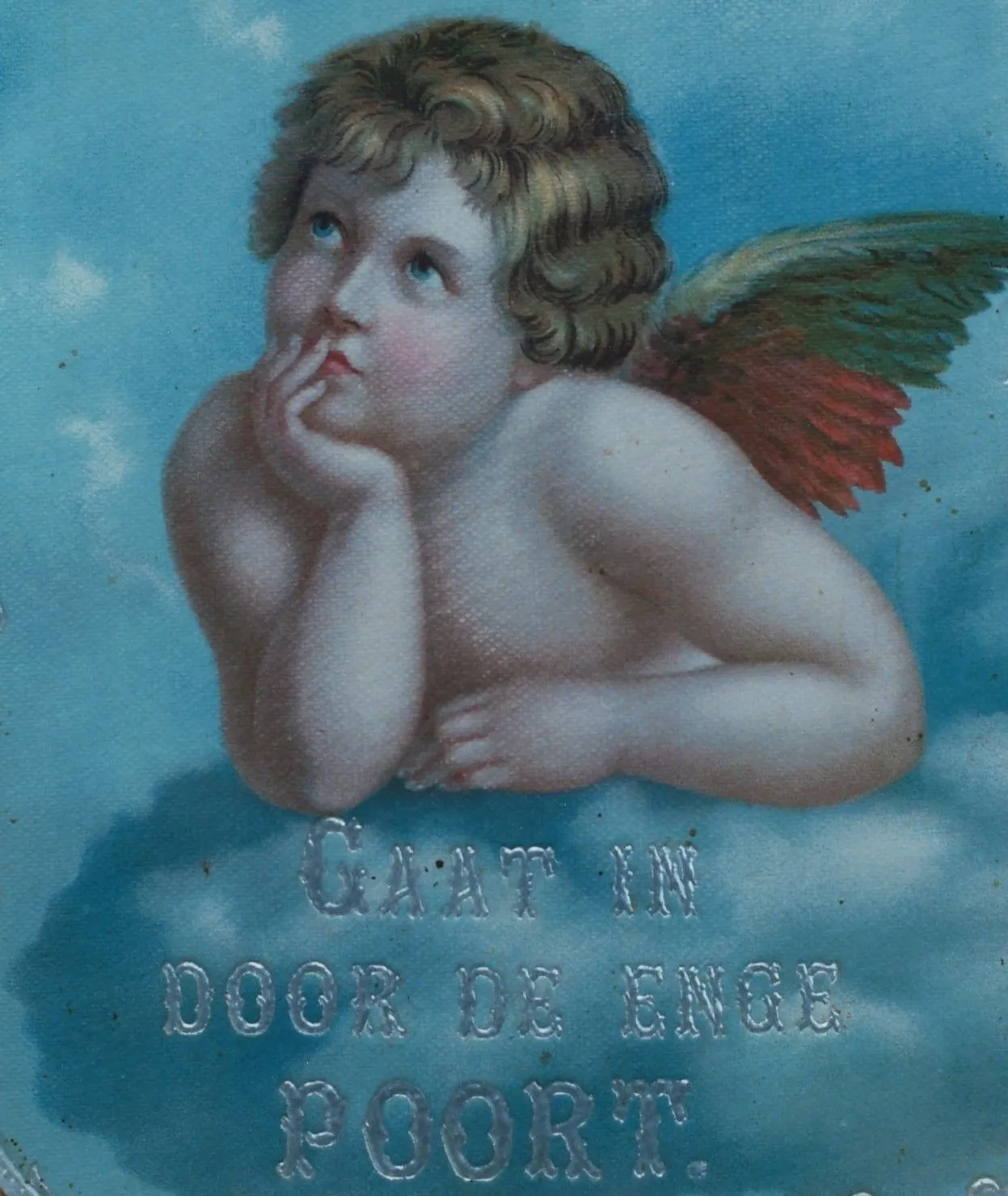

I’ve recently completed Lucky Bastard, a memoir about growing up adopted, in which I inevitably write about my ancestry — both adoptive and biological. While I was working on it, my thoughts strayed to childhood holidays with Ouma and Oupa in Great Brak River. I remember trying to decipher the Dutch biblical inscriptions in silver lettering under depictions of cherubic angels on the bedroom walls. I’m sure these were sentimental mementos Agatha brought with her from Holland, but no one seemed able to translate them satisfactorily. At the time, I couldn’t have imagined that one day Dutch would become my second language. I was still amazed at the shared connection my great-grandfather and I had with Holland and wondered if I couldn’t find out more about him.

‘God’s Blessing is Everything’. Image: Supplied by the author

‘Enter through the Narrow Gate’. Image: Supplied by the author

In his monumental 1996 biography, Langenhoven: ’n Lewe, (Langenhoven: a Life) JC Kannemeyer had the following to say about my Dutch ancestor: “Bloemkolk was born into a wealthy Dutch family but when a bank failed, his parents were reduced to poverty and he was forced to emigrate to South Africa, where he had to survive on a small salary and live in rather more primitive (sic) surroundings than he was accustomed to. He was an intelligent man who spoke five languages and had received instruction in music. But because he lacked the necessary qualifications, he was unable to secure a position in a city or small town and had no choice but to teach at farm schools.” He stresses the influence he had on the young Langenhoven and recycles some information taken from U dienswillige dienaar and Retief Koch’s article.

These were the only facts I was in possession of when I started thinking how to tell my great-grandfather’s story. What really happened? Did my stricken great-great-grandfather enter their house one day, slump in a chair and say, “My son, the bank has failed. We’ve lost everything. I’m afraid you have to leave for the Cape and seek your fortune there.” According to Retief Koch — and this is based on Bloemkolk family lore — he was already in love with Agatha. Did he have to send a portion of his modest salary to his impoverished parents? Wouldn’t it have been more sensible to have found a job in Holland? It made no sense and there was no one who could answer these questions for me.

***

Like most modern-day researchers, I turned to Professor Google and typed in the name “Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk”. And there it was! “Marthinus Paulus Bloemkolk (1850 – 1905) — Genealogy — Geni.” I’d found his family tree — with references to public records — and this provided me with a lot of new information.

To begin with, my great-grandfather was born in Amsterdam and was not from “somewhere in the south”. He died at the age of 55 — not 51. His father, Anthonie Bloemkolk, was an office clerk (kantoorbediende) so he was neither the “son of a rich man” nor from an aristocratic family. His mother, Clara Maria Engelenberg, had been married to a tinker called Marten Erfman and their child Martinus Paulus Erfman — my great-grandfather’s half-brother — was born in 1832. There’s no record of when her first husband died but she married my great-great-grandfather in 1841 and my great-grandfather was born on 1 May 1850. (As he was given the same Christian names as his half-brother, it seems likely that he’d died before my great-grandfather was born.)

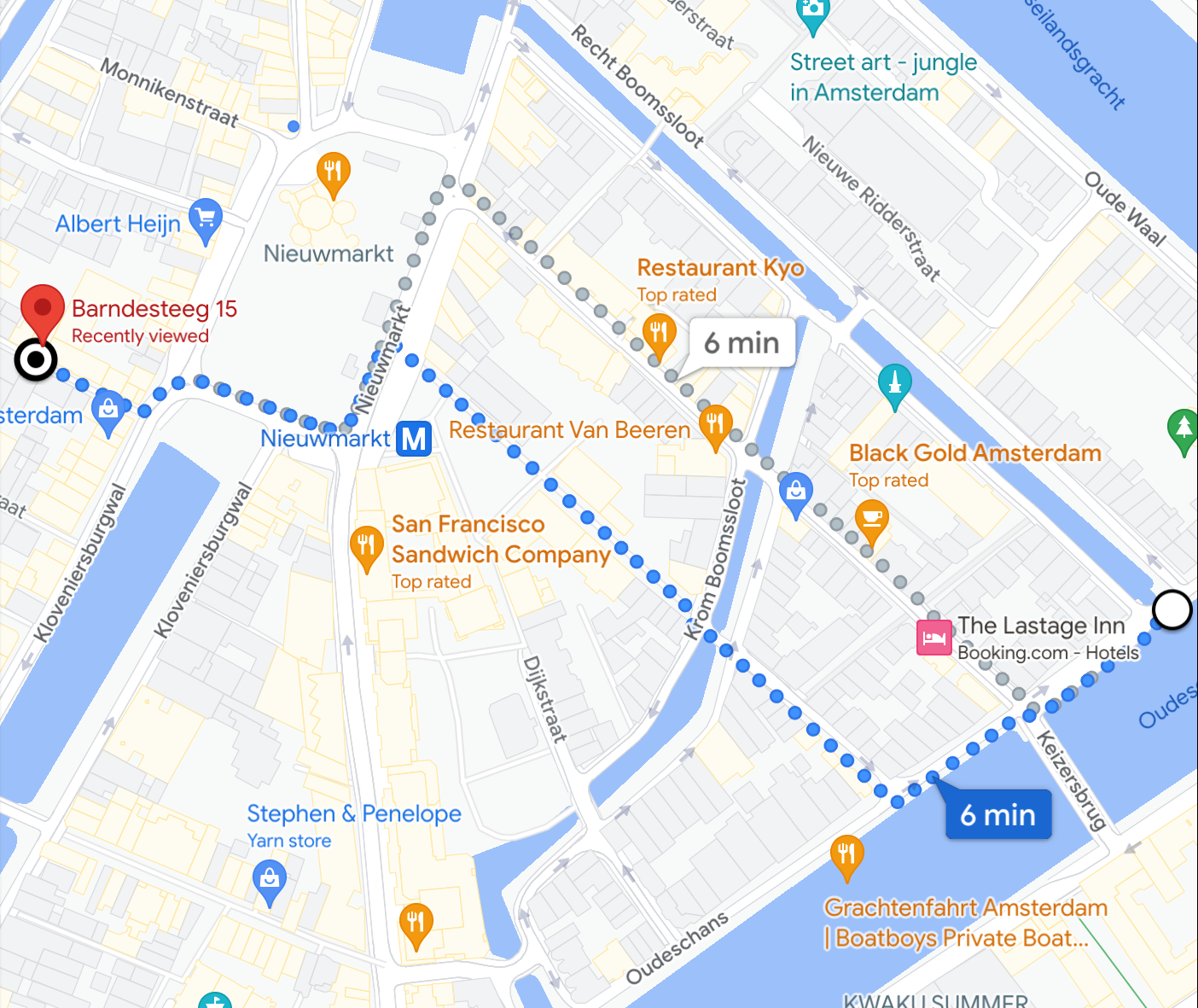

The walk from my flat in Barndesteeg to my great-grandfather’s street. Image: Google maps / Supplied by the author

From 1851 his “domicile” was on a canal called Schans — in full Oudeschans — which, according to the social historian Geert Mak (who also just happens to be a friend of mine), was then a respectable, if not fashionable, Amsterdam neighbourhood. I wished Mum was still alive and I could have told her the flat she’d stayed in when she visited me in Amsterdam was a mere six-minute walk from the street where her grandfather had grown up.

Beschrijving Oudeschans. Image: Jacob Olie / Wikimedial

Both my great-grandfather’s parents died in 1879 and six months later, at the age of 29, he was on a ship bound for the Cape. Why? Why didn’t he get a clerical job in Amsterdam and propose to Agatha? During the 1870s Europe went through the so-called Long Depression but by 1880 there was an upturn in the Dutch economy. Surely he’d have known — as Kannemeyer tells us — that without a teaching qualification he’d only have been eligible to teach at farm schools for a paltry salary. Or did he really have tuberculosis? It remains a mystery. Perhaps he simply wanted to make a clean break after the death of his parents.

But what about Agatha? She was 28 when he left her behind. In 1880, you’d have been forgiven for thinking of her as an old maid. Did he promise to send for her as soon as he had the means to support her? If that’s the case, Agatha Hendrika Negrijn (the correct spelling of her surname) had to wait until she was 33 before she was married by proxy in Haarlem. As her farewell present, her father draped a beautiful red shawl over her shoulders. Soon after her arrival in the Cape, they solemnised their nuptials with a church wedding, followed by a reception at the home of Langenhoven’s foster parents. According to Retief Koch, Agatha always yearned for her family in Holland and Langenhoven said my great-grandfather was so quintessentially Dutch he could never have become an Afrikaner had he lived as long as Methuselah. They never saw their home country again.

***

Just before the lockdown, we didn’t see coming, my wife — the actress and singer André Hattingh — and I visited Great Brak River and then set off for Ladismith. André was born in the other Ladysmith in Natal and this was the first time either of us had visited Ladismith in the Cape. It wasn’t simply an excuse to drive along Route 62 through the Little Karoo, it was also a secular pilgrimage to the place where my great-grandfather had stimulated the imagination of a future writer.

Our first stop in Ladismith was the Tourism Office, which is now located in the deconsecrated, neo-Gothic Dutch Reformed Church designed by the German architect Carl Otto Hager. In all likelihood, this is where Langenhoven was christened and where my great-grandparents had their church wedding. From there we drove through the shimmering January heat along the dirt road that winds through the dry and spectacular Hoeko Valley. When the newlywed Agatha jolted along this road in a Cape cart 136 years ago was she enchanted by the austere beauty of the Swartberg Mountains or appalled as the reality of what she’d actually done began to sink in?

Carl Otto Hager’s church where my great-grandparents got married. Image: Anthony Akerman

Hoeko Valley. Image: Anthony Akerman

Our next stop was “Stillewaters”, the farmhouse where Langenhoven was born (we share a birthday) and where he lived from the age of eight. This is where my great-grandfather lived with him and his foster parents before his marriage.

Stillewaters, where Langenhoven was born and my great-grandfather lived for a time. Image: Anthony Akerman

Image: Historical Monuments Commission

Meester Bloemkolk’s first schoolhouse in Hoeko is on the adjacent farm called Spera. As we drove up to the farmhouse, we were greeted politely by a young farmer. I asked if this was the farm belonging to the Van der Merwe family and he introduced himself as Matthys van der Merwe. I explained that Meester Bloemkolk was my great-grandfather and that I was looking for the old school where he’d taught Langenhoven.

“Then it would be best if Oom spoke to my mother.”

He hit the speed dial on his cell phone.

“Ma, we’ve got visitors from the Bloemkolk family.”

While this was going on we greeted various farmworkers and introduced ourselves to his wife Antoinette.

“Andrea?”

“No, André.”

These days even Afrikaners find it strange that my wife has a “boy’s name”, but we didn’t go into the whole explanation of how she was born into an Afrikaner family that only had daughters and therefore had to take on the names of her father and grandfather.

We were then introduced to Marelise van der Merwe and her husband. He’s related to the Langenhovens and — like Langenhoven’s stepfather — was christened Pieter Guillaume.

“Who’s related to Bloemkolk?”

“I am. He was my great-grandfather.”

“I can see it! I can see the likeness.”

He excused himself as he had to rush off to attend to a problem somewhere on the farm. Was he simply being polite when he said he could see a family resemblance? I could have said I’d been adopted and wasn’t related to Meester Bloemkolk through consanguinity, but it seemed unnecessarily complicated. Besides, I’d really started to feel a strong connection with my great-grandfather.

Marelise had studied under Kannemeyer at Stellenbosch University and was a font of information about Langenhoven. She also mentioned that two of Bloemkolk’s grandchildren — Jean and Pauline — had visited the farm several years ago. I told her Jean was Mum’s sister and Pauline was her cousin — the daughter of Paul who’d been sent to work in the shoe factory when he was fourteen.

We arrived at the little schoolhouse where Meester Bloemkolk once stood in front of the class and, as English was the only permissible medium of instruction, had taught Cape and English History in what Langenhoven described as his “atrocious” English accent. We stepped inside and Marelise turned on the lights. It’s been converted into an attractive and informative museum, with portraits of Bloemkolk and Agatha on the wall behind the table. It’s a fitting tribute to a teacher who once inspired the creative imagination of a writer.

Schoolhouse. Image: Anthony Akerman

Inside the schoolhouse. Image: Anthony Akerman

The following morning, when we woke at cockcrow — quite literally — in the Hoeko Valley, I realised I’d forgotten to sign the visitor’s book. As Spera was on the way to Seweweeks Poort, we decided to call in again. When I opened the book, I saw Jean and Pauline had visited the farm in 2008. Nobody had been there since 2015. It made me sad to think that my great-grandfather and Langenhoven seemed all but forgotten. I took out my pen but I wasn’t quite sure what to write. I began writing something in Afrikaans, then crossed it out. My great-grandfather was Dutch so I wrote, “Bloemkolk was mijn overgrootvader.” André says Meester Bloemkolk guided my hand when I wrote those words.

Yet one mystery remains.

Why did Langenhoven claim my great-grandfather was the son of a rich man and that a financial catastrophe necessitated his departure for the Cape? He said he spoke little about himself and the man he portrayed was nothing like Olive Schreiner’s roguish Bonaparte Blenkins, who’d just made his literary debut in The Story of an African Farm (1883) conning gullible backvelders about his patrician pedigree. So who started the story that led Mum to believe she had noble blood coursing through her veins? We know the young Langenhoven was impressed by this refined gentleman from across the seas with his strange accent, impeccable manners, fashionable clothing and bowler hat. I can see him sitting in his school bench, allowing his youthful imagination free rein and embellishing his story with the stock-in-trade of romantic 19th century novels. So the fantasised story of Meester Bloemkolk’s early life, with all its dramatic reversals, may well have been Langenhoven’s first work of creative fiction — a story he told himself so often and so well, he’d come to believe it by the time he wrote his autobiography and paid tribute to his beloved first teacher. DM/ ML

In case you missed it, also read When Abraham lost Israel – the saga of a missing child

A LOVELY and well penned story, Anthony Akerman. Thanks for sharing this important, but almost forgotten, part of SA history. Circumstances permitting, I have every intent to visit the old schoolhouse.