OP-ED

My friend André Brink, the Afrikaner roots I didn’t want, and the secret I wish I’d told him

Like many first-year drama students, I’d hang around the Rhodes Little Theatre because it was more entertaining than writing the essay that had to be handed in the following day. That’s how I came to be watching the technical rehearsal of André P Brink’s play, ‘Elders Mooiweer en Warm’.

The boards of the state-subsidised Provincial Arts Councils found his work problematic and would often first delay, then cancel, scheduled productions of his plays. Although Elders had been published in 1965, it still remained unperformed in 1969. Brink hoped a university production would convince the pusillanimous decision-makers at the arts councils that it had artistic merit. On this occasion it worked, because he was invited to direct the play for the Performing Arts Council of the Free State (Pacofs) in Bloemfontein the following year.

I’d heard of André Brink and it made my day when he noticed me hanging around and asked if I’d lend a hand. So I held onto one of the flying lines in the wings while they set the tabs to mask a lighting bar. I’d been told Brink was a Sestiger – one of a loose grouping of writers who’d assimilated the latest trends in world literature and whose work almost inevitably questioned the reactionary orthodoxy of the Afrikaner political and religious establishment. This encounter with Brink was not only memorable because I’d met a famous writer. Most importantly, it made me re-examine my prejudices against Afrikaners.

I grew up in parochial Hillcrest when that part of Natal liked to think of itself as the Last Outpost of the British Empire and Afrikaners were considered “socially inferior”. The monolingual English were also fond of saying Afrikaans was not a language but a throat disease. Although my surname wasn’t as English as Windsor or Mountbatten, if someone at school called me “Afrikaner vrot banana”, I’d indignantly explain that Akerman was not an Afrikaans surname. My great-grandfather was Sir John Akerman. He’d been knighted by Queen Victoria. I bet you can’t lick that!

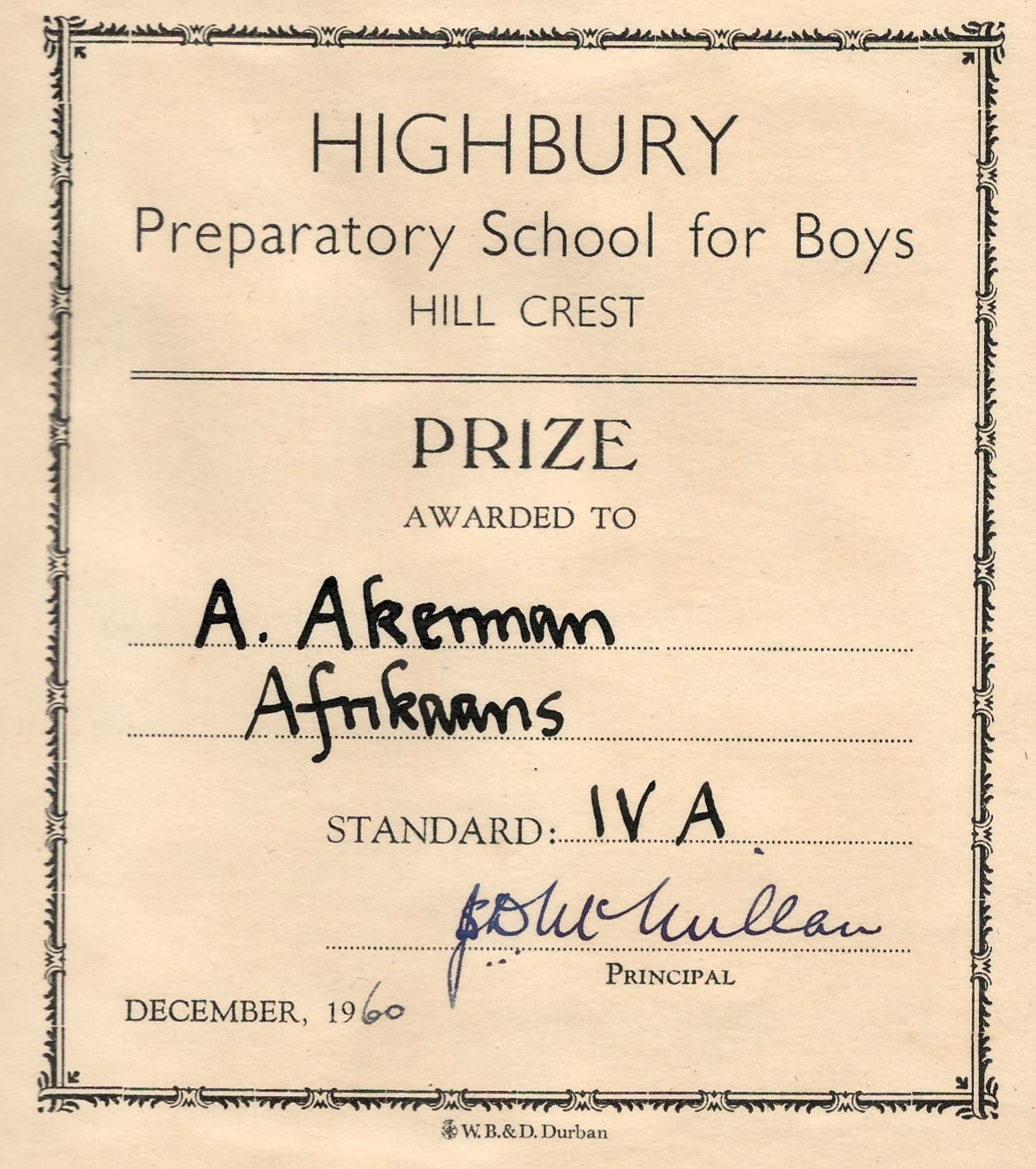

Then, problematically, there was Mum’s family in Great Brak River. Although my mother said the Honiballs were descended from British 1820 Settlers, we called our grandparents Oupa and Ouma. They were also rather poor and, before meals, Oupa said grace in Afrikaans. But what happened in Great Brak River stayed in Great Brak River. As long as Mum didn’t speak Afrikaans on the phone when friends came around to play, my world was safe. Then, in Standard 3, I won the Afrikaans Prize. Without even trying. Oupa’s mother had been a Rademeyer from Louterwater. Was some occult Afrikaner ancestry manifesting itself in my aptitude for the language?

Author Anthony Akerman’s Afrikaans Prize from Standard 4 in 1960. Image: Supplied

I hoped I’d be spared the embarrassment of winning the prize again in Standard 4, but I wasn’t. 1960 was precisely when I didn’t want to be good at Afrikaans. Dr Verwoerd had announced plans to hold a referendum on becoming a republic and – so I’d been told – that meant we could kiss goodbye to both “God Save the Queen” and the English language. This explains why, as a 10-year-old, I thought David Pratt had struck a blow for my freedom when he shot Verwoerd at the Rand Easter Show. It happened at the height of the space race and I went around repeating a tasteless riddle my parents strongly disapproved of. Q: “Who was the first man to shoot into space?” A: “David Pratt, because he shot Verwoerd in the head.” My glee was short-lived. After a successful operation, Verwoerd recovered, South Africa became a republic and, although I defiantly refused to sing Die Stem, I was relieved to discover I was still allowed to speak English.

If the republic referendum had been a watershed moment, 1960 had a second one of those in store for me. I was told I’d been adopted. The downside was I didn’t have a real great-grandfather who’d been knighted by Queen Victoria. On the upside, I also didn’t have a real great-grandmother from the Rademeyer family in Louterwater. But this all suddenly seemed less significant when I realised I had no idea where I came from – or who I was.

If I was no longer sure whether I had English or Afrikaans ancestry, the Afrikaner NCOs in the army had little doubt. I was regularly derided for being a soutpiel and an Engelsmannetjie. When I got to university, every English-medium campus in the country had a rival Afrikaans-medium campus to offset their supposedly liberal ethos and thrash them on the rugby field. On our campuses, boys had long hair, girls had short skirts, we smoked dagga, listened to Bob Dylan and were spied on by the Security Police; on their campuses, boys had short hair, girls had long skirts, they smoked Camel, listened to Charles Jacobie and queued up to join the Security Police. If that was stereotyping, it worked for me – until I met André Brink.

If he made me rethink my prejudice towards Afrikaners, I still felt the same way about the Afrikaner political establishment. Of course, that establishment didn’t approve of the likes of Brink either. It would have been easier for them to dismiss him had he not written in Afrikaans. One of the defining constituents of Afrikaner identity was the language and writers who elevated the language into a vehicle of literary expression enjoyed a special status – as long as they didn’t stray from the straight and narrow. That’s a big ask because it’s in the nature of most creative writers to question what others consider to be self-evident – including the status quo – and it’s probably only the hacks who don’t stray from the straight and narrow. This goes some way to explaining the ambivalence the establishment felt towards Sestigers like Brink. For example, after Elders he was scheduled to return to Bloemfontein to direct Chekhov’s The Seagull for Pacofs but the administrator decided to cancel the production because he refused to allow a “volksvreemde” influence like him to work in the Free State again.

I suppose I was also dimly aware of his reputation as a ladies’ man. I remember him going out with a student – something that would be unthinkable today. Then he met and married Alta Miller and they started a family. I’d also heard he had an ex-wife and a son living in Grahamstown, but I wasn’t really all that interested.

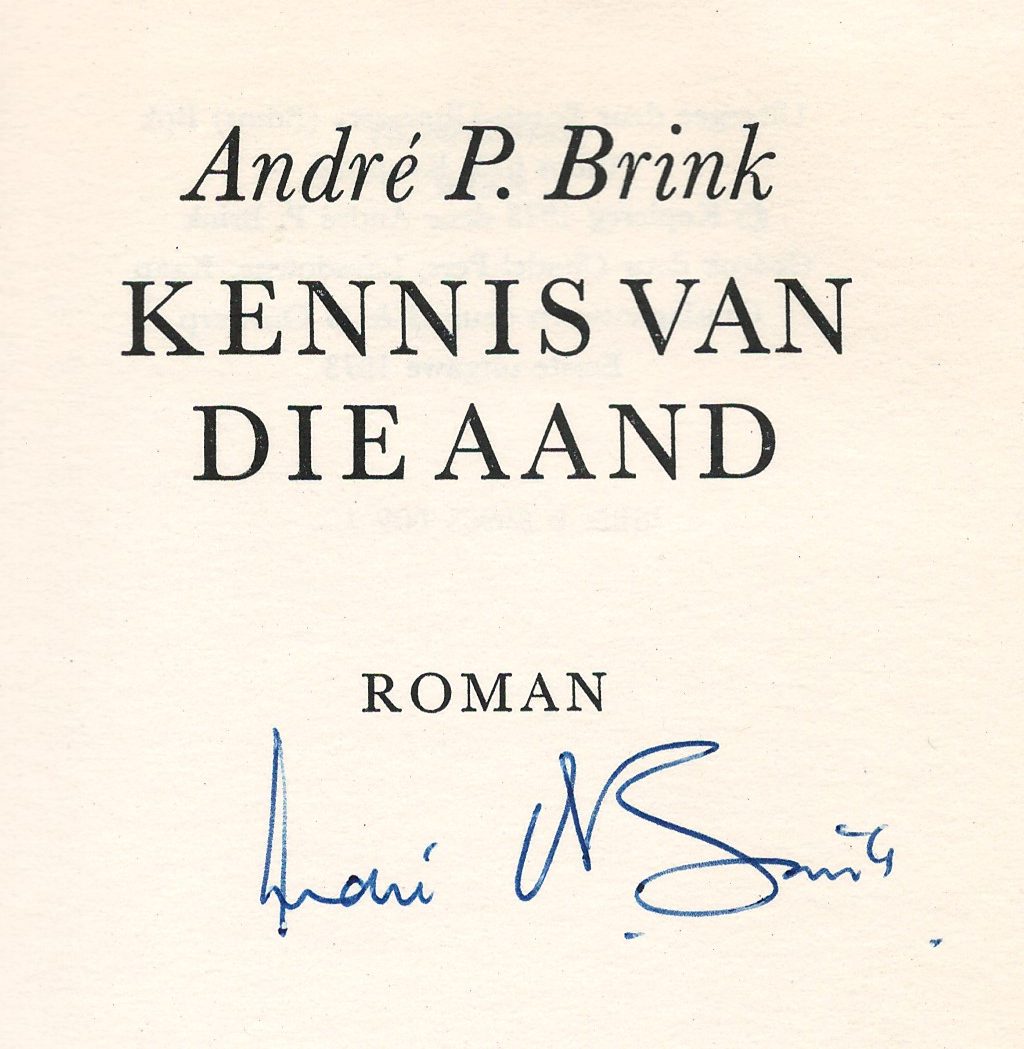

Signed copy of ‘Kennis van die Aand’ by André Brink. Image: Supplied

Although Brink was on the staff of the Department of Afrikaans-Nederlands, he also gave inspiring lectures to students in the Drama Department. What he had to say about playwrights such as Lorca and Pirandello opened new worlds and whetted my appetite to know more. Despite his teaching load and prodigious literary output, he made time to give me guidance and lent me books from his personal library. He lived in a historic home on Market Street – now The Cock House – and the walls of his office on three sides were lined with bookcases going up to the high ceiling. It was here that he finished writing Kennis van die aand. Koot Vorster, Moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church and brother of Prime Minister BJ Vorster, secured his place as a footnote in literary history with his pronouncement on the novel’s artistic merit. “If this is literature,” he solemnly opined, “then a brothel is a Sunday school.”

I was already at theatre school in the UK when André wrote and told me Kennis had had the dubious distinction of being the first Afrikaans novel to have been banned in South Africa. By then we were friends and regular correspondents. Admittedly, some of our epistolary exchanges were to monitor a mutually beneficial arrangement we’d come to. Every month I posted the banned magazines Playboy and Penthouse to different safe addresses and, in exchange, he posted cartons of Texan cigarettes to my theatre school in parcels labelled “used theatre slippers”.

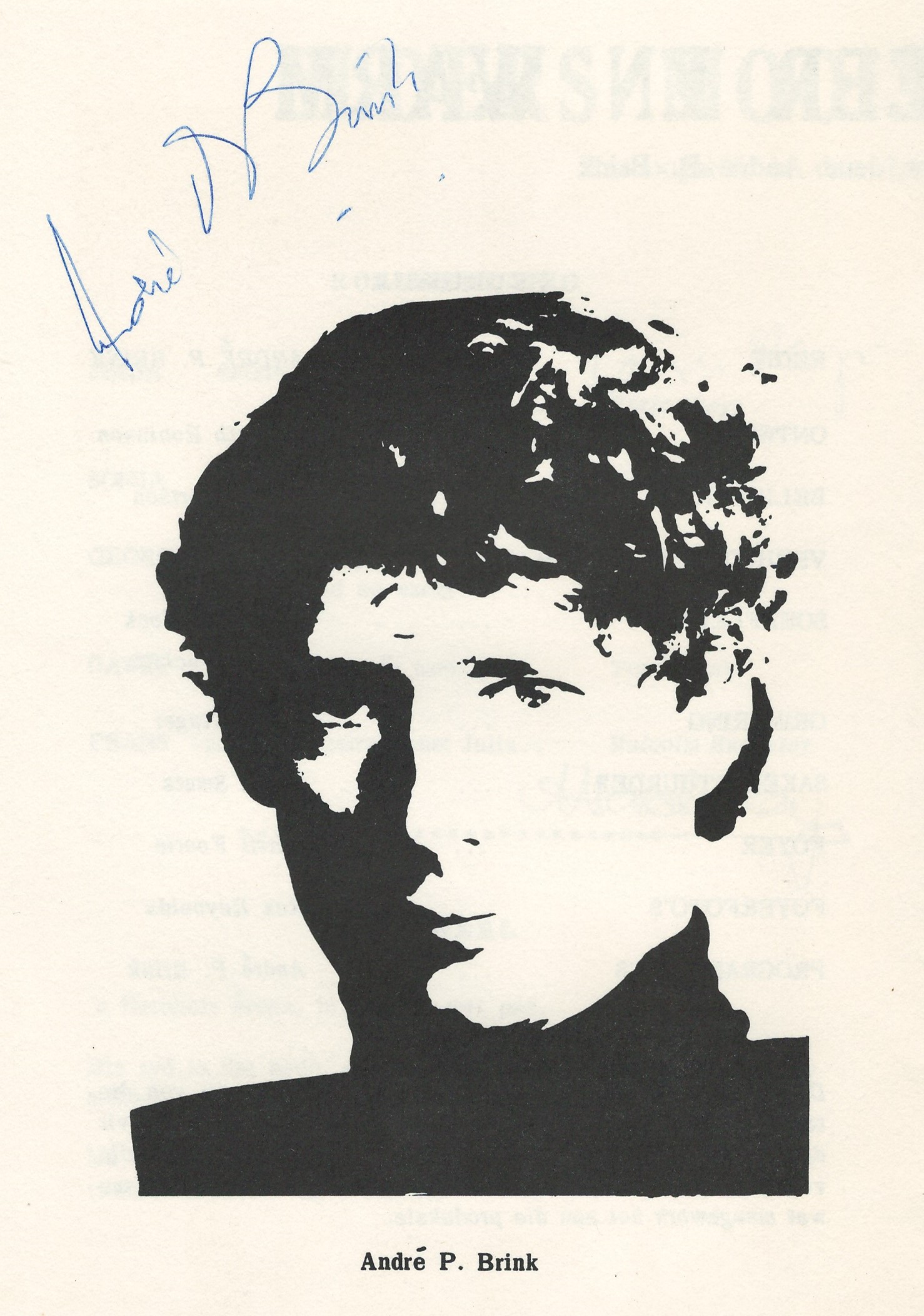

Programme of André Brink’s play, ‘Elders Mooiweer en Warm’. Image: Supplied

André had told me about Pavane, a “political” play he’d written, which, like Elders a few years previously, was in an abusive relationship with the performing arts councils. When he first submitted it to Capab in 1971, he received a dismissive letter saying: “We are not prepared to degrade our theatres by presenting the idiosyncratic political misconceptions of certain frustrated authors.” In 1973, the same man wrote again requesting permission to stage a workshop production of the play. André agreed. When he saw it in performance, he thought it “very mediocre”. Afterwards, he revised the script in the hope that François Swart, who liked the play, would direct it for Pact. In June 1974, Pact wrote to say they’d provisionally put it on their programme for the following year, but then there was a backlash from “verkrampte committee members” and the production was shelved.

By then I’d enrolled for a postgraduate course at the University of Cardiff’s Sherman Theatre and André offered to send me the script. “Who knows,” he wrote “it may even be staged at the Sherman Theatre!” As it happened, I was looking for a play to direct. The only hitch was that Pavane was in Afrikaans and André didn’t have time to translate it before the production slot I’d been given. So I offered to translate it myself. I’m not sure what convinced him I was up to the task, but I probably didn’t let on that – apart from winning Afrikaans prizes at junior school – my highest academic qualification in Afrikaans was a third-class pass from the University of Natal at the end of my first year. On my next visit to London, I entered South Africa House as inconspicuously as possible and bought an Afrikaans-English Dictionary. Although it was a student production, the British premiere of Pavane was well received.

The following year I went to Amsterdam to direct the Dutch premiere of an Athol Fugard play. My plan was to return to England afterwards, but I ended up staying for 17 years. When people asked if I had Dutch ancestry, I told them my Akerman ancestors had come to South Africa from England, but then added that I was adopted and so I had no idea about my genetic ancestry. They invariably nodded sympathetically, studied me closely and said I could quite easily have Dutch ancestry. In 1983, I renounced my South African citizenship and became Dutch.

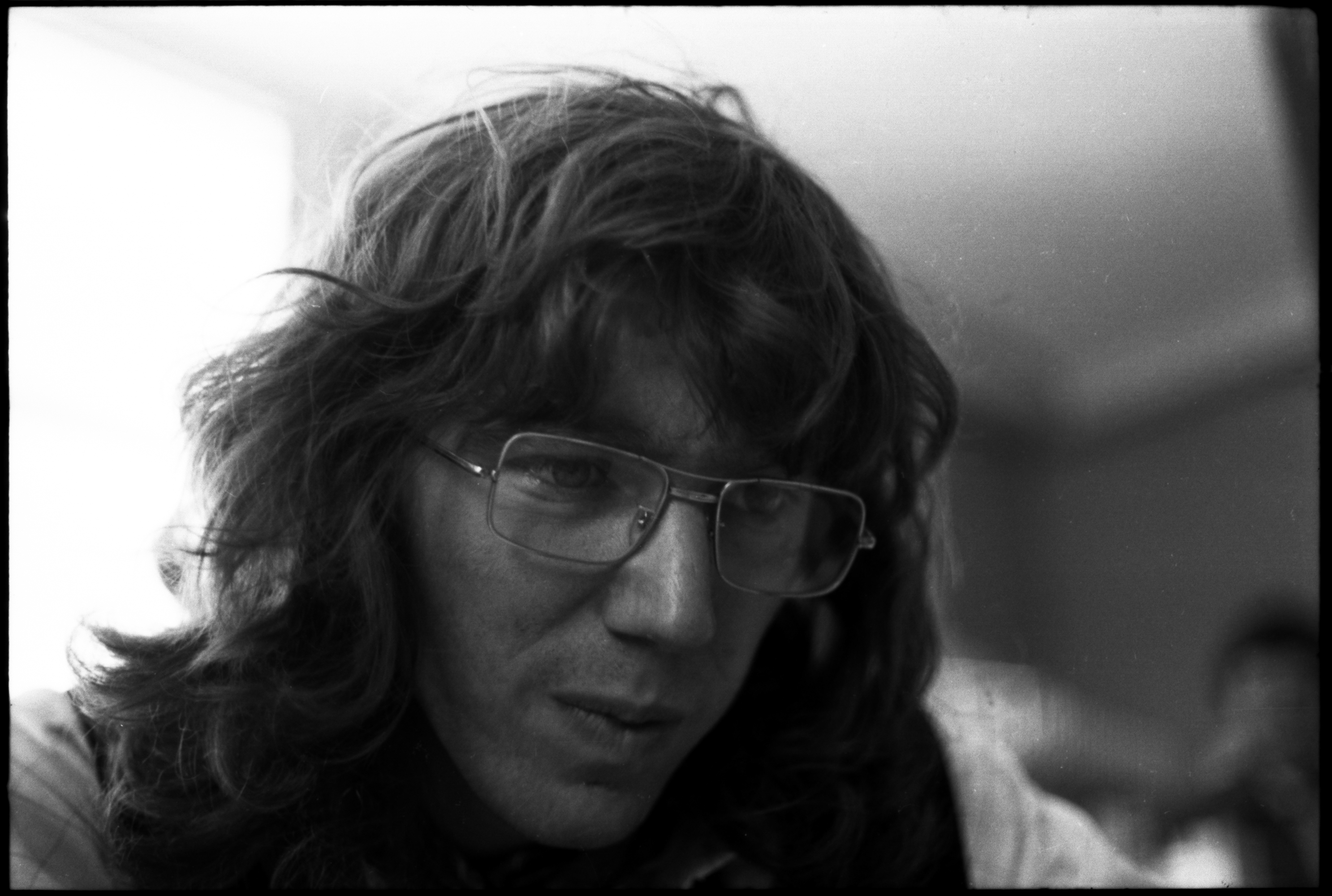

Anthony Akerman in 1971. Image: Giles Hugo

In the same year, the South African Parliament enacted the Child Care Act No. 74, which made it possible for adoptees to search for their biological parents. In 1989, I was fortunate enough to trace my birth mother in Cape Town. She was willing to have contact, but we were only able to meet face-to-face after Nelson Mandela’s release because I’d recently been refused a visa for South Africa. In the interim we exchanged letters. She told me who my father was and answered questions about my ancestry. The Universe also gave me a lesson in irony when I discovered my genetic make-up was predominantly what passes for Afrikaner. Something else she wrote gave an ironic perspective on my fierce opposition to Dr Verwoerd in 1960.

“I was the theatre sister when they operated to remove the bullets after he was shot at the Rand Easter Show by David Pratt.”

That caught me off guard. There were other surprising coincidences, but only one is relevant here. When filling her in on the first 40 years of my life, I obviously mentioned that André Brink had taught me at university and that we’d subsequently become friends. In a letter from her dated 19 May 1989, she wrote:

“I know André Brink. In 1959, for a while, I shared a flat with a Mrs Naudé and her daughter Estelle was engaged to André. He often came to the flat & slept over there. When they got married I was her unofficial bridesmaid in that I took her bouquet when he put the ring on her finger!”

She also told me that she and Mrs Naudé had been on a package tour of Europe in 1960. By then André was at the Sorbonne and he and Estelle had joined the tour group in Paris and travelled with them to Spain and then to the Olympic Games in Rome. She enclosed a photograph taken on that holiday which she told me was not for public viewing because she looked “too dreadful – a real SLUT!”

What are the odds? My biological mother had been the bridesmaid at André Brink’s first wedding! André and I hadn’t communicated in a while, but this seemed a good reason to reignite our correspondence. Before I got around to doing so, however, Vera asked me not to tell him. She’d suddenly become concerned about her reputation. I told her I couldn’t think of anyone less likely to judge her than André Brink, but she was adamant and I felt I had to respect her wishes.

Vera Farnham, André and Estelle Brink and Mrs Naudé in Spain 1960. Image: Supplied

When I returned to South Africa, I settled in Johannesburg and André was in Cape Town. Our paths seldom crossed and I felt obliged to keep Vera’s secret – until I came to the inescapable conclusion that I was the shameful secret posing a threat to her chaste reputation. So I decided to tell André when I next saw him. But we only encountered each other on public occasions – his book launches and the opening night of a play of mine in Cape Town – and the right moment never seemed to present itself. The last time I saw him was 10 years ago at the Johannesburg launch of his novel Philida. We eventually found ourselves alone at a table with a bottle of white wine. I’d like to think that’s when I was going to tell him, but before I could do so Beyers Naudé’s daughter-in-law came over to speak to him and the opportunity was lost.

André died in 2015 and Vera two years later. When Vera took Estelle’s bouquet at André’s first wedding, I was 10 years old. Ten years later I walked into the Rhodes Little Theatre and André asked me to hold onto a flying line during a technical rehearsal. He became a mentor and friend and I’m indebted to him for making time for the callow student I was. I regretted I’d never told him about the connection we’d shared before we met. It felt like an unfinished story, a dangling loose end and – for writers – that’s always dissatisfying.

In 2020, I contacted André’s oldest son, Anton Brink. He’d been 10 when I left Rhodes and now he’s a well-established artist. He was amused to hear I’d been the source of the “girly mags” he’d discovered as a teenager and surreptitiously perused in his father’s study. I told him about Vera and sent him the photo of his parents and grandmother with my mother.

Wow, what an interesting connection! Estelle says she remembers Vera well, and that her mother was very fond of her.

If Estelle was surprised to hear Vera had been the mother of a 10-year-old illegitimate son when she was her bridesmaid, she didn’t let on. I still can’t believe I never got around to telling André. It occurred to me that he may not have been all that interested and may not have remembered the 31-year-old nurse who held Estelle’s bouquet while he put the ring on her finger.

But the other day I came across one of his letters that changed my mind. It’s dated 3 October 1975 and in the opening paragraph he remarks – somewhat irrelevantly – that it was his dog’s second birthday. Then he added, “and if I’d never got divorced it would have been the sixteenth anniversary of my first wedding”. DM/ML

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Wonderful story, showing how lives can, unknowingly, intersect and interact. Thank you for sharing this!

Lovely story brilliantly told.

I’ve recently found that my South African lineage is not Irish/English/Scottish as thought but Dutch and my family have been born and raised in this country since 1667! Quite a shock to discover my Afrikaner roots but very proud now to call myself an “Anglosized Afrikaner” and a true South African.

What size is that? Anglo-sized.

Truly a complicated world we live in…and even more so in South Africa. I just hope my kids can grow up being themselves, despite all the prejudice.

Thanks for sharing these memories.

@Jane, is is not so bad be Dutch and South Africa. Embrace it!

[‘Most importantly, it made me re-examine my prejudices against Afrikaners.’]

I loved that story.

What a fascinating story. Thank you for sharing it. It is amazing how things came together for Anthony Akermann. Facts are truly stranger than fiction.

I so enjoyed reading this story. I had to laugh (now ashamed) at the rank prejudice against Afrikaners with which most of us in KZN were raised. Inevitably, there was that Afrikaans ancestor in many families. In my case great-grandmother Sinnie Bezuidenhout!

Beautiful. Thank you