BOOK EXTRACT

A Russian On Commando: The Boer War Experiences of Yevgeny Avgustus

In December 1900, the enthusiastic but inexperienced young Russian officer, Yevgeny Avgustus, set off for the Transvaal to fight in the Anglo-Boer War. This extract from ‘A Russian on Commando’ describes his arrival on the Natal front where he met General Piet Joubert, who commanded the Boer forces, and Otto Krantz, who led the German volunteers. ‘A Russian on Commando’ is published by Jonathan Ball.

Like distant peals of thunder, the sound of cannon fire rumbled, then faded gradually in the air. There it was!

My heart sank painfully as if in foreboding at the realisation that something terrible was happening on the other side of those mountains, beyond that dark blue horizon. Perhaps at this very moment in the trenches, people maimed by lethal shrapnel were writhing in the throes of death, and the last echoes of that discharge had been drowned by moans and screams. Then another boom rang, and another, and yet one more!

I was entirely gripped by an ineffable feeling — the awareness that I should face at last that dreaded and yet unfamiliar phenomenon of war made me forget my hunger, thirst and exhaustion after the two-day journey by train, and I rode on as if being lured forward by some strange and fatal power. Massive table-like mountains towered in front of us; beyond them lay entrenched the troops under the command of White (General Sir George Stuart White commanded the British garrison at the Siege of Ladysmith), who had turned Ladysmith into a new Plevna (During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1912 troops of the Ottoman army besieged the town of Plevna for five months).

To the side of the road, in a valley through which there wound a small river, we noticed white tents. We had reached our destination.

We had arrived, as we learnt later, at the camp of the Pretoria District; General Joubert’s headquarters was also here.

Tents and marquees of different shapes and sizes were pitched across the slopes of the small mountains that bordered the valley with its winding river. Bulky covered wagons loomed in the spaces between the tents; pyramids of sacks filled with maize and rusks were kept under tarpaulin shelters; the entrails of slaughtered cattle and empty tins were scattered everywhere.

The Boers had just finished their lunch; blacks squatted round the smouldering fires licking clean the pans and pots in which their masters’ food had been cooked. The sleepy, sunburnt faces of the bearded Boers glanced at us from the tents.

Yevgeny Avgustus (with glasses) with his scouts in Siberia after an expedition to Mongolia in 1908. (Photo: Supplied)

It took us quite a while to get some sense out of them and establish the whereabouts of Joubert’s tent. Finally, at a spot in the middle of the camp, we saw a large green marquee crowned by the four-colour flag of the republic. In the tent, at a table buried under papers, sat the Kommandant-Generaal, commander-in-chief of the allied armies of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, Piet Joubert. He was alone.

The five of us entered the tent, and I, with some agitation, began a speech I had prepared earlier in my head, explaining that we had just arrived, that we would like to join a commando on the Tugela, and that we were “at his command”.

Joubert raised his head slightly, moved the papers aside, took his glasses off and surveyed us with his penetrating gaze. He enquired where we came from and why we did not wish to remain at Ladysmith.

We answered that the siege was of no interest to us. After the unsuccessful attempt of 6 January, it seemed unlikely that the Boers would attempt another assault.

“Jammer om de mannen te slachten! (It would be a shame to sacrifice the men!) The British will surrender anyhow,” Joubert replied.

While he was writing a letter to General Lucas Meyer for us, I had time to study the interior of the tent, which probably served as a venue for meetings of the Krijgsraad [military council].

A telephone attached to the middle pole, a dozen bentwood chairs and a large table with papers heaped on it in great disorder: these were all the furnishings. Among the papers I noticed a blue large-scale map of Natal, reports by field-cornets with many pencil markings, and copies of the English-language Cape Times and of the Volksstem, published in Pretoria.

Handing us the letter and shaking our hands, Joubert said, “Alles van de beste”’ (All the best!) The audience was over.

“That general headquarters is something!” Nikitin grumbled. “They don’t even have any adjutants or orderlies!”

“Such spartan simplicity!” Diatroptov gushed.

We began looking for our horses, but at that moment a gentleman in spectacles and a yellow British jacket came up to us and explained that he had ordered the horses to be unsaddled and allowed to graze. He introduced himself as a former lieutenant of the Prussian Army. We were delighted to accept his kind invitation and followed him into the tent, where we found about six other volunteers. Our welcoming hosts, who had already been under fire, fully supported our decision to join a commando near Colenso and gave us food and drink, and one of them even volunteered to guide us to Lombardskop.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

It was hard to imagine that this volunteer, with his worn jacket, tanned face and bristly beard, had formerly been a wasp-waisted premier-lieutenant (platoon leader). The lieutenant and his comrade, an artillery captain, approved of my choice of unit.

“In the foreign commandos there is always quarrelling, scheming and disagreements; their superiors, elected by the volunteers from their own ranks by a majority of votes, command no respect; the German corps, which is the largest, has been completely discredited among the Boers, and the Italian and the French commandos are in fact just looting under the pretext of conducting reconnaissance that is of no need to anyone.”

I told him about our conversation with Joubert.

“‘Jammer om de mannen te slachten!’ is the cornerstone of his tactics; quite rational, however, as you will realise later. The Boers have splendidly implemented the principle of saving men while inflicting the biggest possible losses on the enemy. Just try not to show off when under fire; the Boers regard any unnecessary bravado as rashness and only laugh at it.”

It turned out that the Tugela was about six hour’s riding away and that we could leave that very afternoon for the camp of the German corps, where we would find our fellow countryman, a Russian officer by the name of Shulzhenko. The camp was located to the southeast of the Platrand, and from there it was only a three-hour ride to Meyer’s headquarters.

Two Germans volunteered to be our guides. We agreed, saddled up our horses, took leave of our gracious hosts and set off, hoping to sleep over at the camp of the German corps.

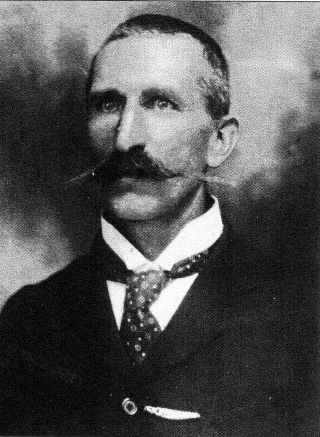

Otto Krantz. (Source: Unknown)

One of our new companions taught me the necessary rules of riding, and in particular how to control Boer horses, strong and hardy Basotho ponies. At one of our rest halts, he adjusted the straps of my flasks and saddlebags and proved to be cheerful and witty company.

“You’re going to be in the front position, face to face with the khakis. Don’t even think of getting bored if things don’t get serious in the beginning. Remember that the two most important things in war are patience and good digestion.”

I couldn’t help but recall the half-forgotten pages of Mayne Reid’s novels about the lives of the first settlers in the region. So here they were — the thorny acacia shrubs of the South African bush with their small, feathery leaves and sharp thorns. One moment the horses’ hooves would ring loudly on the layers of hardened red clay, devoid of any vegetation, and the next moment they would sink into a soft carpet of bright-green grass dotted with red and white geranium flowers.

Field partridges, as well as some sort of long-tailed bird with plumage that glittered in the sun, would fly up from under the horses’ hooves, flapping their wings and emitting piercing cries.

Occasionally, the graceful silhouette of a springbok would appear on the hills, only to take fright at the clatter of our hooves and disappear in a few jumps into the thicket of sprawling acacia.

But nowadays one no longer encounters the massive herds of giraffes and antelopes of former days; the distant plains no longer resound with the mighty roar of the king of the animals or the lingering howl of jackal. In half a century of persistent labour, man has conquered this land; ploughed fields now mark the mountain slopes and riverbanks. Vast pastures lie hedged in by barbed-wire fences, and poplars and fruit trees from Europe have proliferated around the farms.

But now the walls of ruined farmhouses, abandoned by their inhabitants, stand ashen and forlorn. More and more we came across pits dug in the earth by grenades, tatters of rotting uniforms, shell fragments and rifle casings — a battle had taken place here on 30 October…

We crossed the Klip River through a fairly deep ford that reached up to the horses’ chests. The current was swift and the crossing not without incident: one of my comrades was swept 20 paces or so to the side; his horse stepped into a pit and capsized, and the rider would have become food for the fish had not some Boers appeared on the other bank right at this moment, jumped into the water and fished him and his horse out.

After this little adventure, which provoked general laughter, we took off at a gallop to reach the camp before nightfall. In the south, day quickly gives way to night: as soon as the last rays of sunset were extinguished in the west, the constellation of the Southern Cross sparkled in the dark-blue sky and everything around us sank into impenetrable gloom.

Our guides dismounted and led their horses by the reins; we followed suit. We stumbled over rocks, scratching our faces and hands in the thorny acacia branches, until we had all climbed to the top of the hill, and at last could see a little light burning somewhere in the distance.

“Just another half an hour!” the Germans consoled us.

Another half an hour! My legs were burning, my back hurt from the heavy Martini-Henry rifle, and my horse held its head down and was barely moving. The unwelcome cold bath and the cool evening air forced us to spur our horses on so that we could reach the camp before dark…

They led us straight into the tent of Commandant Otto Krantz. A German who had lived about ten years in the Transvaal, he was elected the commander of the German volunteers on the strength of his reputation as a well-known lion hunter; in his lifetime, he had killed exactly 68.

“And my wife… Oh, wait until I introduce you to my wife! She’s personally shot a whole 86!”

Mrs Krantz, The Sphere, 15 Sep 1900. (Photo: Supplied)

He managed to tell us all this while attending to his duties as a host. He was a short, restless man with a big, well-groomed moustache, and bustled around us, carrying in crockery, pouring each of us a cup of hot coffee and serving us meatballs and flat ash cakes. All the while he talked incessantly, telling us about his participation in the assault of 6 January, that it had been his idea to build a dam and flood the besieged town, and about his determination to storm Ladysmith again if given 500 men.

We listened to him reverently, drinking cup after cup, and devoured an enormous pan of delicious meatballs. DM

Boris Gorelik is a writer and scholar from Russia specialising in the history of Russian-South African cross-cultural encounters. He is senior research fellow of the Institute for African Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. His works have been published in Russia, South Africa and the United Kingdom.

The book was translated from Russian to English by Lucas Venter, who studied Russian at the University of the Witwatersrand in the late 1980s and worked as an announcer and translator at Radio Moscow World Service in the early 1990s. Venter also taught Afrikaans at the Diplomatic Academy of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Moscow. He currently lives in Pretoria.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.