COMMITTEES, COMMISSIONS AND CONSEQUENCE

Waning potency and lack of authority may put special commissions of inquiry out to pasture

High-level legislative committees and special commissions can have a real role in democratic societies to call the bad guys to heel. But do they?

In both South Africa and America, commissions and committees have been big news. In South Africa, the Zondo Commission, after years of testimony, investigations and multiple extensions on its deadline has finally delivered its findings in a multi-volume set of conclusions and recommendations.

These have corroborated — and built on — reporting by numerous media organisations (including this one) that have given substantive flesh, and more than a shudder of horror, to what is now universally labelled “State Capture.”

Meanwhile, in America, the public hearings of the House of Representatives select committee on the events of January 6th 2021 have ground on. It has been setting out for all to see the full extent of an insurrectionist conspiracy aimed at discarding the results of the 2020 presidential election and installing a president through a mass riot, executive fiat, false pretences and extra-legal means.

On the surface, both efforts have been a search for the truth about deeply unpleasant, even seditious, efforts to undermine the rule of law, although their mechanisms and relationships to governmental authority are significantly different. The question becomes: Will the results from their intentions be similar? The answer to this question will be crucial for the futures of both nations as republics that operate under law, as opposed to a descent into deeply troubled, corrupt autocracies.

Historically, special commissions are convened to investigate a major national calamity, but in an examination deemed too politically sensitive, too catastrophic, or too all-encompassing to be the province of any one pre-existing body or branch of government.

Most often, they are set up with members appointed with the expectation they will be free to dive deeply into the issue without worrying — too much, at least, as this is still the real world — about whose circumstances or comfort zones will be disturbed, or whose reputations will be sullied — through the course of their investigations, hearings, and findings.

In the best of all worlds, a commission points the way toward the necessity for new policies or governmental actions that previously would not have been considered as politically feasible since they would have been “too hot to handle”.

US inquiries

Let’s look at American examples such as the Kerner Commission set up in response to widespread, racially charged urban unrest in the 1960s, a similar commission on the causes of violence in the nation that spun out of that first commission, and the Warren Commission, established in the aftermath of the assassination of president Kennedy in 1963.

With the first commission, the decision to establish it came from the president, based on the reasoning there must be a mix of policies that, if adopted, could ameliorate — or even help heal — the national angst and anger, and, especially, improve the economic, political and social circumstances of the nation’s African American citizens.

In the second commission, the idea was that the underlying causes of a growing texture of violence in American life could be changed through better social and political programmes, as well as dealing with the growing scourge of easy access to firearms. The reasoning was that a non-partisan, dispassionate body of eminent persons could articulate a path forward for the country, even as it held on to the support of a majority of the nation for proposed reforms.

With the Warren Commission, also presidentially appointed, its fundamental purpose was to solve a publicly witnessed murder of a president. The commission’s task was to understand how such a crime could have occurred, to weigh all the evidence wherever it led, to address the deep trauma that had flowed from that death, and to reassure a shattered nation such an event was not about to become a terrifying new reality for American politics.

In each case, it was clear the more usual mechanisms of national political life were inadequate to address these national traumas. Accordingly, non-partisan bodies, but with the active representation of elected officials from both major political parties, with other respected individuals, would be best for instilling public confidence in the outcomes.

President John F Kennedy delivers a speech at a rally in Fort Worth, Texas, several hours before his assassination on 22 November 1963. (Photo: JFK Library / The White House / Cecil Stoughton)

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the conclusions of the Warren Commission on president Kennedy’s assassination failed to quell whispers that the so-called truth about the assassination (as perpetuated even now on social media, and in popular books and films about a massive conspiracy involving shadowy government operatives or foreign intelligence operatives) have never been revealed.

In the case of the two commissions on racial issues and the causes of violence, while their messages and assembled evidence have been devastating, very little of any programme of action evolving from their recommendations has ever been enacted. Too many vested interests were in the way, and implementing those recommendations could have upended major parts of the national political and economic landscape. In short, the recommendations were deemed unrealistic for the then-political climate (or even now, as well).

The problem, of course, is that such commissions, and others appointed in the same manner, have no executive authority to carry out actual policy changes. Their limited power is to issue reports or recommendations. At best, they may affect the national discourse by changing the way a problem is described and debated by political leaders and others. But at worst, they can feed a counter-narrative that either the truth has never been allowed out, or that the powerful will never make the changes so urgently needed.

That, in turn, just generates greater public cynicism towards politicians and the political landscape. “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” — the more things change, the more they stay the same, becomes a cynical retort.

By contrast, a formally constituted congressional inquiry does hold real powers, derived directly from the legislature’s role under the nation’s constitution. These can include the authority to subpoena documents and records, as well as witnesses to testify, and, perhaps most importantly, to recommend to the department of justice individuals for indictment and prosecution for a wide range of crimes, including lying to Congress under oath, along with the other more usual forms of criminal activity.

In more recent times, congressional inquiries have increasingly become comfortable with using the media to focus public attention on their efforts, and the subjects of their inquiries. Important, too, in the process, has been the presence of a strong opposition party willing to push back in the face of presidential or other misdeeds, and to be able to co-opt at least part of the president’s party into participating in the investigations — rather than obstructing them.

Back in 1973, the Senate select committee on Watergate under North Carolina Senator Sam Ervin was able to make use of national television broadcasts for full coverage of the hearings.

Those hearings (and their successors heading towards an impeachment and conviction) were the stage for revelations about the lawbreaking and criminality of the Nixon White House — including that moment when knowledge of a full-time taped record of Oval Office discussions was revealed, thereby making it virtually impossible for any political figure, or the general population, to say, “I didn’t know.” (The still earlier Army-McCarthy hearings in the 1950s had helped destroy the malign influence of Senator Joe McCarthy with his shambling, wild charges about Soviet communist infiltration into the military and the state department. While those hearings had removed McCarthy as a national figure, the impact of such hearings via excerpts on broadcast television had not yet made congressional hearings an all-consuming feature of public life.)

In our own time, the House of Representatives’ select committee on the insurrection of January 6th and then-president Donald Trump’s complicity in it, has taken the use of mass media to a new level through live, nationwide broadcasts. Drawing on the talents of television professionals skilled in building and sustaining a dramatic narrative arc, this congressional committee has been adept at delivering a compelling storyline, using both pre-recorded and live testimony from actual participants and legal experts, and, crucially, eschewing the usual temptations to allow congressional members to preen or pontificate lengthily, allowing the story to be the lead character instead.

This format seems designed for our age with its growing reliance on social media and instant messaging, rather than long, drawn-out debates and equally long (and boring) speeches. Whether this is, ultimately, good for the national discourse, may be too early to say. But, importantly, it is the universe we do live in.

South African inquiries

For comparison, look at two of the most influential examples of South African commissions designed to uncover and document particularly difficult, painful truths: the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the TRC) and now, most recently, the Zondo Commission. In both cases they were rightly concerned with core issues confronting the South African state — the nature of the apartheid state and how it so deeply affected the lives of so many of its victims; and, now, how the State Capture conspiracies defrauded so many state institutions, allowed the theft of the institutions’ resources, and then hollowed out national institutions.

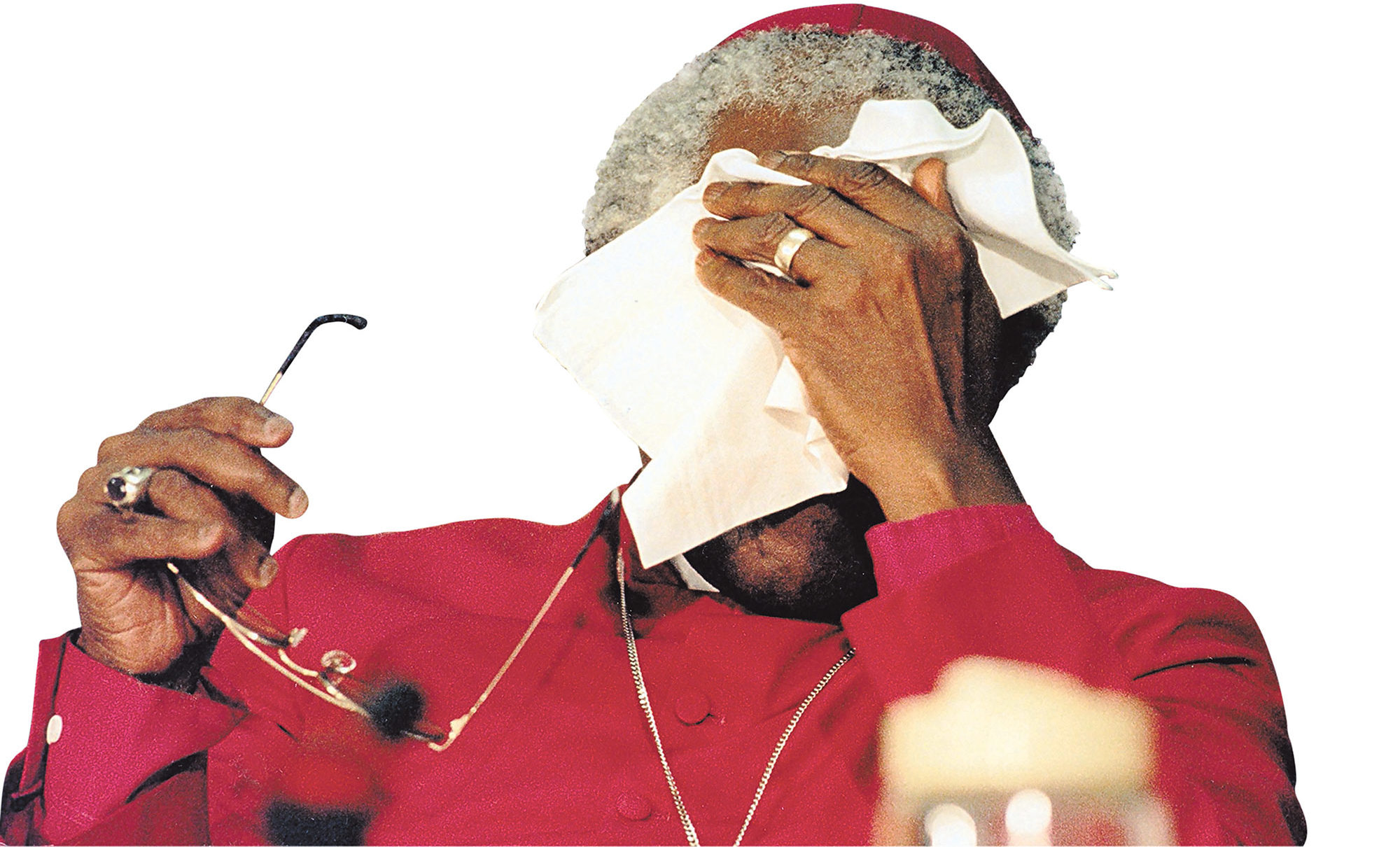

The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu in tears at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sunday Times)

Both commissions have received harrowing testimony concerning the country’s history. In the case of the TRC, the commission embraced what it termed its role to issue a kind of secular absolution over decades of atrocities — as long as there were full confessions. Some atrocities were sufficient to drive the TRC’s chair, the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, to public tears over what he and the other commissioners had heard.

In the case of the Zondo Commission, from nearly half a decade of hearings, research and analysis, and finally a bookshelf’s worth of reports, the commission described a vast web of systematic corruption and looting that has now grievously damaged crucial state-owned enterprises — through illegal alliances of unscrupulous politicians and business people.

Chief Justice Raymond Zondo hands over the fifth and final Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State Report at Union Buildings on 22 June 2022 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Alet Pretorius)

But what neither commission was able to achieve was to compel testimony or issue mandatory subpoenas of documents whose identity came to light from testimony, let alone to create mechanisms for the mandatory restitution of looted assets or the indictment, prosecution or conviction of those responsible for alleged crimes. Sadly, the TRC was never able to compel testimony by some of the chief figures in the apartheid regime, despite promises of immunity upon full and complete disclosure.

Meanwhile, the Zondo Commission’s sessions, as remarkable as they often were, often presented a nearly soporific litany of legal motions and further representations within motions, as attorneys for witnesses (and the commission’s staff attorneys) jousted in legal manoeuvres that could leave the main thrust of the question lost in the thickets for the average viewer.

Perhaps this was because, unlike the US Congress’s January 6th select committee, the Zondo Commission’s leadership seemed prepared to let the evidence lead them where it would, as it played out, no matter how long the testimony, stalling, prevarication and evasiveness took to be delivered, rather than with the commission itself having developed a cogent narrative it would demonstrate ruthlessly via the testimony. Too often, then, the nature of the commission as a tool of public education about high-level criminality could become missing in action.

Perhaps this was because the commission, being led by judges — individuals presumed to be impartial — rather than by some sharp-elbowed political figures, meant that a crisp, critical edge was often missing in the way the storyline was laid out for the viewer via television. Perhaps the Zondo Commission could have used, like the January 6th committee, some TV professionals — or perhaps a documentary filmmaker — given the complexity of the tale they had to tell.

This matters, since in the absence of being able to compel the restoration of stolen funds or issue sentences, the real audience for the commission’s work is not just government lawyers who may (or may not) elect to indict some of the conspirators. It is also the nation’s public who now insist on a better way of doing the government’s business. Connecting all those complex swirls of dots, therefore, was crucial.

Taken together, these American and South African experiences all point to the importance of delivering a coherent, compelling narrative for the larger body of citizens. Citizens need to understand the need for outrage over the traducing of democratic principles and honesty in government, and for commission staff to work in ways such that prosecutors have evidence “ready for prime time” in achieving indictments, trials, convictions and, where appropriate, restitution.

But the saga of commissions and committees also points to the fact that absent rigorous political will, recommendations are just that. Reports can occupy shelves, but those who are undoubtedly guilty may evade judgment. Commissions and committees are, significantly, exercises in public education, at least as much as the determining facts, such that a public can insist their politicians and leaders step up and do the right thing, rather than the expedient one. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.