Despite the incredible job the Zondo Commission did, some of my colleagues feel the commission lacked one crucial aspect: it failed to provide an overarching analysis of why the corruption happened. And consequently, the commission’s recommendations are kinda haphazard, from suggesting a permanent commission of some sort, to suggesting a directly elected President.

Perhaps the real problem is that at least some of the suggestions might overlap with political programmes that are the domain of the political system. Or maybe, after spending more than R1-billion and four years on the job, they were keen to finish up and head out to the bar.

Because I like to blunder in where angels fear to tread, allow me to try, in an off-the-cuff way, to suggest some aspects that an overarching analysis might contain.

There were so many different parts of this investigation and so many different situations, it’s hard to bring them all together. But, in essence, I think it’s kinda simple. Although the types of corruption were different, they had one overriding thing in common: state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The South African Social Security Agency, Eskom, Transnet, Prasa, Alexkor, Denel. There is almost no major SOE that didn’t appear somewhere in the commission’s work.

And the question is this: Why are SOEs so prone to corruption?

A long time ago, I agreed to debate an up-and-coming member of the ANC Youth League by the name of Julius Malema. The league had taken the controversial position of recommending the forced nationalisation of mining companies, and I had disagreed in a newspaper column. I had, by chance, met some of the youth league members on a radio show debating the issue, and they invited me to go one step further and participate in a debate on the issue at a public gathering.

Like an idiot, I agreed. The meeting took place at a hall around the corner from Wits, and as we approached the hall, the entire hall broke into freedom songs that may or may not have suggested the appropriate action would be to disembowel the traitor from the “anti” camp. That would be me. There was dancing and singing and all the usual political meeting stuff. Because I’m observant by nature, I remember thinking this was not going to be an easy crowd, and there was in fact a good chance I would end up being an ex-human.

I shouldn’t have worried. Malema himself was considerate to a fault and set the rules in such a way that, for one, disembowelment would not be considered a legitimate debating tactic. We had a fractious but fruitful discussion. There was a vote at the end. Shockingly, I lost.

Ever since then, I have wondered how to convincingly argue the issue, particularly since I had so humiliatingly failed, albeit at a gathering where minds were definitively made up. And, you know, I just don’t think there is a logical argument that wins here. What has to happen is experience; deep, personal, painful experience.

The logical argument is really simple: the accountability systems in SOEs are geared towards the political process and not the sustainability of the business. In the end, the business fails. It’s obvious. Sometimes, the accountability systems coincide, but never for long, and never completely. Senior positions in SOEs are almost always handed out to friends or family of some party official. And that would qualify as a “good” outcome. The “bad” outcome is that senior positions are handed over to charlatans from another country.

Yet, voters around the world, in country after country, just somehow feel that SOEs can do things private companies cannot or will not do. And you can shout until you are blue in the face that this has never worked, except in the most exceptional circumstances, but it doesn’t help.

Almost every country on Earth has tried it, including the UK, France, Germany and China of course, and many continue to try it. It’s worth noting that Brazil has just come through a huge corruption scandal that ousted an enormously popular government. And the company at the centre of the corruption was – hold on to your hats – an SOE.

There are countries in a certain band that are very susceptible to the deceptive lure of SOEs and corruption, and they have much in common: often, they are one-party states or single-party dominant states, they are often middle-ranking countries economically, and they are almost always run by left-wing governments. SA ticks all those boxes.

Consequently, the recommendation that the Zondo Commission should have come up with is precisely the recommendation that possibly it could not come up with. And that is a strongly worded recommendation that the government should urgently and immediately get out of the SOE business.

The commission does have a recommendation that SOE board appointments should be selected by a non-politically partisan organisation, with representatives from business, trade unions, Nedlac, etc. Not a terrible idea, but there is a logical conundrum here. If your board is going to be non-political, what is the actual point of the SOE being owned by the state?

Some tentative steps have been taken by this government to at least change the structure of SOEs. But, to be honest, it’s only situations where the SOE in question is already a parrot. But there is no wholesale move by the government to decisively restructure the 500-odd SOEs it notionally runs. And Zondo does not recommend the government should.

But, actually, it should. Because history. And logic. It would have been helpful if the commission had said that. DM/BM

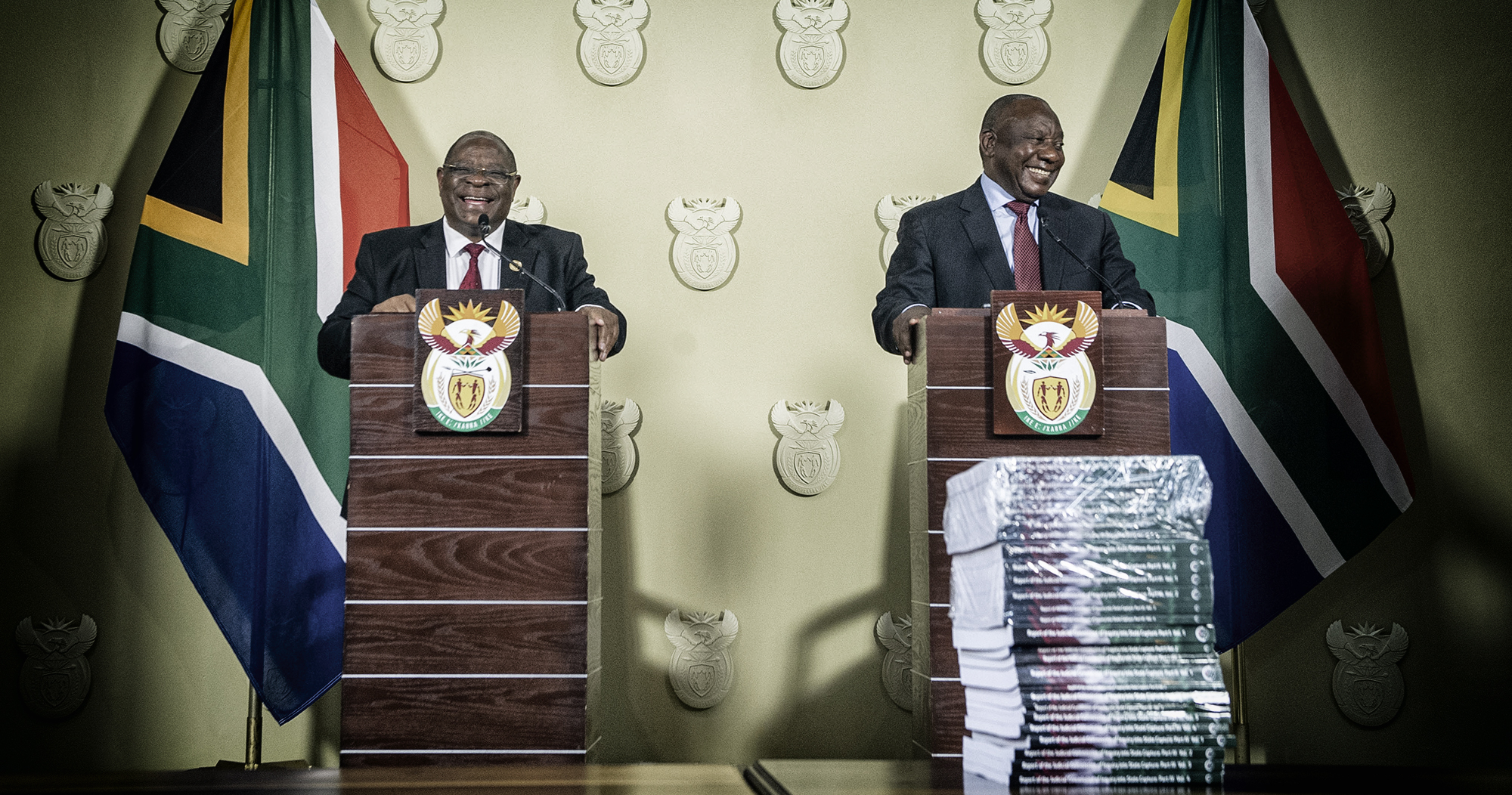

President Cyril Ramaphosa receives the fifth and final report of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture from Justice Raymond Zondo at the Union Buildings on 22 June 2022 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Alet Pretorius)

President Cyril Ramaphosa receives the fifth and final report of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture from Justice Raymond Zondo at the Union Buildings on 22 June 2022 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Alet Pretorius)