OP-ED

Reflections of a Wayward Boy: Squatting on Hampstead Heath

For all my tendency to optimism, I have always harboured a degree of caution. So, when we sold up everything in New Zealand and shipped ourselves and more than a ton of books and other educational gear to start the ANC primary school in Tanzania, I kept back 1,500 Swiss francs (R4,800 at the time), secreted in a money belt, ‘just in case’. It turned out that it was just as well I had taken the precaution.

Having left the ANC school in Tanzania, we were in quite desperate need of three things when we arrived in Britain: accommodation, transport and work. We had been told that we could expect no help from the ANC in London which, as Zarina, wife of ANC leader Mac Maharaj, noted in her memoir, was dominated by “a ruling clique of mainly Stalinist types”. They had, she said, “appointed themselves as owners-in-exile of the South African revolution”. And they had apparently spread a distorted view of my dissidence.

As a result, we were personae non gratae with the majority of ANC officials and members in London. But we had support in a few senior circles, and among some rank-and-file members, so we could not be wholly isolated. I also rejoined the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) and met up with some colleagues I had known both in the 1960s and in New Zealand.

We were also able to get about because of my emergency fund. At an informal travellers’ market on London’s South Bank, we bought an elderly converted Commer van. It could sleep the four of us, had a gas cooker, a shower and chemical toilet. I also bought a suit, tie and briefcase: we had accommodation, transport and the sartorial requirements for job seeking.

Ensconced in our van, we discovered, by pure chance, that there were two free parking spaces in the centre of London, alongside the Serpentine in Hyde Park. If we got in as soon as the park opened in the mornings, we could park for the day, without charge, right in the centre of London. So while Barbara and the children walked and explored London as part of an expanded educational exercise, I trudged about looking for work as a casual subeditor.

That turned out to be much less of a problem than finding where to spend the nights. It was impossible, it seemed, to stop anywhere for more than a day or two before drawing the attention of irate neighbours and the police. And so we became masters at what we called “squatting on Hampstead Heath”: this entailed rotating our parking in a seven-day cycle. We would park in a different road each evening (usually over a drain, to allow our shower and dishwash water to disappear without notice) in one of the generally genteel suburbs surrounding this famous park. By early morning, we would be gone.

From such peripatetic lodgings, I went off to sub-edit for a period the letters pages of the Daily Mail, write and edit sections of a part-work on military technology while also working on the women’s pages of The Observer. I then landed a permanent job with The Observer, production editing the 16-page business section.

This was a time when the free market orthodoxies of what became known as Thatcherism and Reaganism were rampant. Social housing was being destroyed and – in the name of creating a “property-owning democracy” – 100% mortgage bonds were quite readily available to anyone with a job. It was also at the start of a property price wave which we were able to join and ride. But, at the same time, it was the start of the disputes that led to the bitter 51-week strike by British miners fighting to preserve their jobs and keep collieries open.

Reserve Bank smoked out Guptas’ money laundering Bank of Baroda before State Capture findings

Solidarity with miners

Since the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) had been one of the staunchest supporters of the anti-apartheid struggle and of the ANC, I felt that the self-exiled South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu) should at least express support for the NUM. But Sactu representative Zola Zembe (Archie Sibeko) was adamant: “This is a British matter. It has nothing to do with us.” It was a far cry from the days when, as the ANC Youth in London, we had marched against British support for the Vietnam War.

So, as “independent South African workers”, Barbara and I built connections with, and supported, Kent Miners and those at Hatfield Main in what ended as a major defeat for labour. It was followed by the first hints of what the Fourth Industrial Revolution might mean in the defeat – after a 54-week strike and weekly mass protests – at Rupert Murdoch’s hi-tech Wapping print plant. There were also ongoing campaigns against local racism.

The only glimmer of optimism came, ironically, from South Africa, especially after Moses – “Moss” – Mayekiso, then Transvaal secretary of the Metal and Allied Workers’ Union (Mawu) visited London. We became friends after I met him to find out what I could about the emergent – and militant – new trade union movement in South Africa. Like ourselves, he was shunned by the ANC establishment, being dismissed as a “workerist”.

But he impressed local trade unionists, mainly because he gave receipts for any money received and asked that any donations to Mawu be sent to the union’s bank account. It underlined the fact that the international banking system could not be banned by the apartheid state; that overt support for unions was possible. I also introduced him to Donald Trelford, editor of The Observer, a fact that was to prove important less than a year later.

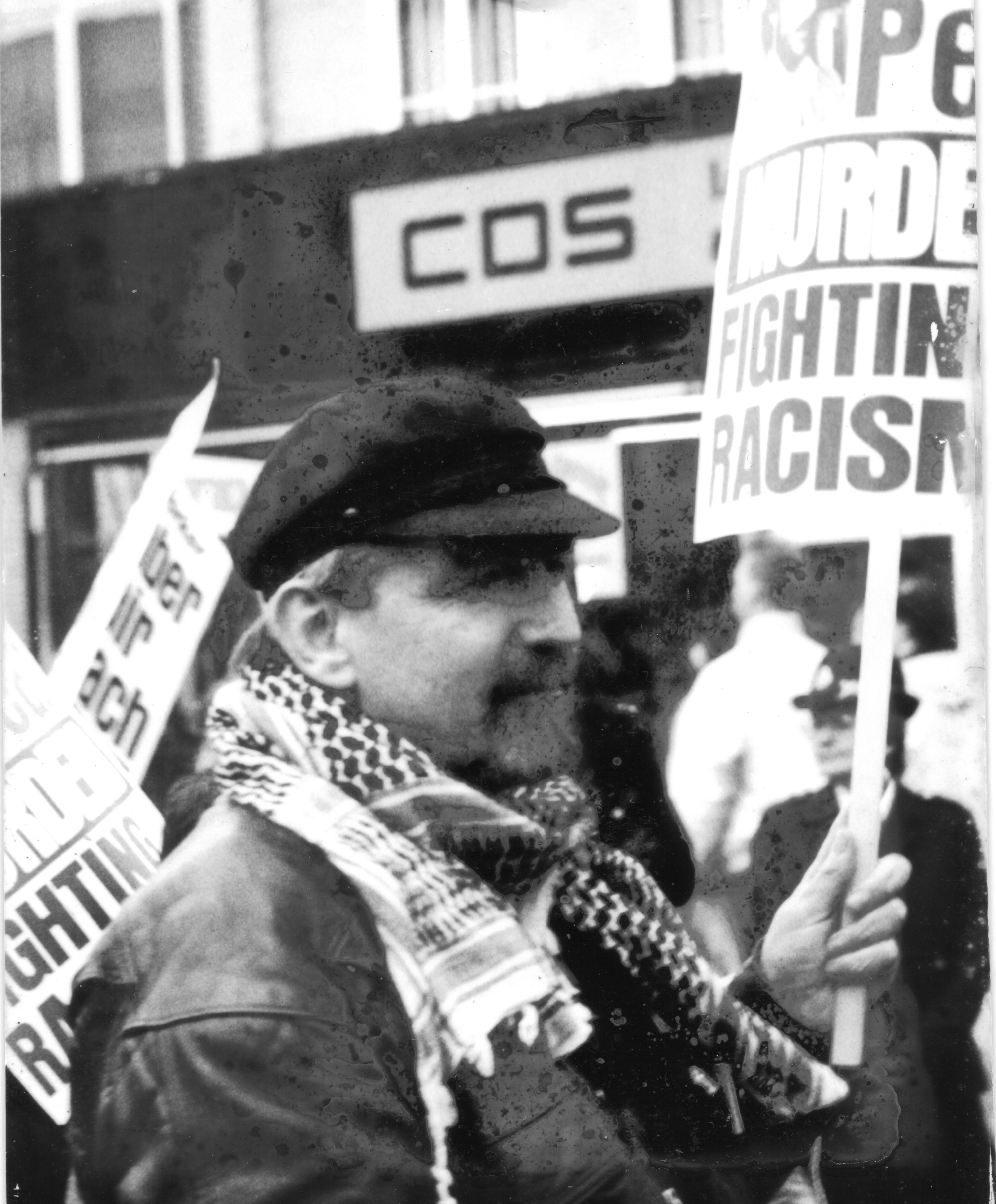

Protesting in London in a time of rampant Thatcherism and Reaganism. (Photo: Supplied)

After Moss left, we maintained direct links with Mawu and, later, after a union merger, with the National Union of Metalworkers (Numsa). A prime initial focus was the campaign to support the 970 workers in Edendale, outside Pietermaritzburg, who were sacked by BTR-Sarmcol for daring to start a union.

Then, in 1986, only days before the 12 June declaration of a national state of emergency in South Africa, Moss was sent by his union to Sweden to build support for the burgeoning South African union movement. When he was scheduled to return home, I arranged that someone at the airport in Johannesburg would let me know if he was arrested. I could then “make a stink” hopefully to ensure that he did not simply disappear. I would notify The Observer, but also relay the information to the major anti-apartheid rally in Hyde Park scheduled for that afternoon.

Early on Saturday morning, 28 June, Moss Mayekiso was taken away by security police. I notified Shyam Bhatia on The Observer, and Barbara and I headed for Hyde Park where we informed senior ANC figures, among them Essop and Aziz Pahad, about the arrest. Essop was one of the speakers on the platform before a crowd estimated at 50,000. But there was no mention of the arrest.

However, Observer editor Trelford understood the importance of the detention of one of South Africa’s leading trade unionists: Bhatia’s report was on the front page, along with a report on the Hyde Park rally. Over the next week, I had regular contact with Mawu and the newly formed Cosatu federation as they launched a “Free Comrade Moss” campaign that would be coordinated internationally by the International Metalworkers Federation (IMF) in Geneva.

The unions in South Africa and the IMF agreed with my suggestion that a “Friends of Moses Mayekiso” campaign be launched, based in Britain. And so, in July 1986, the campaign got under way with only two registered “friends”, Barbara and me. But it struck a chord, especially with organised labour around the world: unions representing more than 30 million workers eventually signed up, along with politicians, actors and pop stars.

It also saw us described in print as “vermin”. DM

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9472″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.