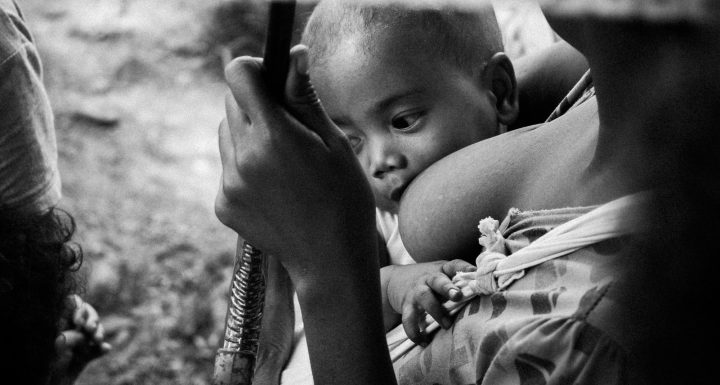

CHILD NUTRITION

Breast milk substitutes — why we should always prioritise health over profits

Exclusive breastfeeding is still uncommon in South Africa, with breast milk substitutes commonly used in ways that are often detrimental to infant and young child nutrition, health and survival.

The World Health Assembly adopted the International Code of Marketing of Breast milk Substitutes forty years ago, and yet inappropriate marketing of breast milk substitutes continues, putting infants and young children at risk of malnutrition, illness and sometimes death. This is not the case only in South Africa but around the world.

Published on 11 February 2022 in the online journal BMJ Global Health, a paper dubbed, “Conflicts of interest are harming maternal and child health: time for scientific journals to end relationships with manufacturers of breast milk substitutes”, explores “how a manufacturer is using a leading scientific journal to market breast milk substitutes through paid advertisements and advertisement features”.

According to the team of researchers, “the $57-billion (and growing) formula industry engages in overt and covert advertising and promotion and extensive political activity to foster policy environments conducive to market growth sabotages global breastfeeding promotion and support. This includes health professional financing and engagement through courses, e-learning platforms, sponsorship of conferences and health professional associations, and advertising in medical/health journals.” The team adds that this directly impacts mothers’ motivation to breastfeed, “irrespective of country context”.

The researchers in the paper highlight that it also creates “a subtle, unconscious bias and conflict of interest, whereby journal publishers may consciously, or unconsciously, favour corporations in ways that undermine scientific integrity and editorial independence — even perceived conflicts of interest may tarnish the reputation of scientists, organisations or corporations.” There is no doubt, they say, that breastfeeding should be supported and encouraged — for the child’s health benefits, and that “companies that advertise and promote their breast milk substitutes in ways that contradict the International Code of Marketing of Breast milk Substitutes (the Code) violate the rights of children to be fed in the best possible way and mothers to make informed decisions about infant feeding.”

The Code

In 1981, the World Health Assembly (WHA), part of the World Health Organization (WHO), adopted the International Code of Marketing of Breast milk Substitutes as a minimum requirement to protect healthy practices concerning infant and young child feeding by regulating the marketing of breast milk substitutes, bottles, and teats. The WHO Code bans all promotion of bottle feeding; however, the WHO explains that the ban does not mean that the products cannot be sold or that factual and scientific information about them cannot be made available. Nor does it restrict parents’ choice. It simply aims to make sure that their choices are made based on full and impartial information rather than misleading, inaccurate or biased marketing claims.

The Code also sets standards for the labelling and quality of products and for how the law should be implemented and monitored within countries.

Ubiquitous and aggressive marketing

Breastfeeding substitutes are currently advertised and promoted as the best and closest to breast milk through journals and other mediums, which is false and misleading advertising. According to a report of a multicountry (including South Africa) research study commissioned by the WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund, launched by WHO on 23rd February titled How the marketing influences our decisions of formula milk, shows that 51% of the 8,528 pregnant and postnatal women surveyed reported seeing or hearing formula milk marketing in the preceding year.

“Self-reported exposure to marketing is highest among women in urban China (97%), Vietnam (92%) and the United Kingdom (84%), and is also common in Mexico (39%). In these countries, marketing is ubiquitous, aggressive, and carried out through multiple channels”.

The study further explains that traditional marketing, such as television or advertisement is less common in Bangladesh, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa, and that in these countries the effects of marketing can be seen in “recommendations from health professionals and on digital platforms, and recommendations from health professionals are a key channel of formula milk marketing”. In fact, health professionals in the study spoke of receiving commissions from sales, funding for research, promotional gifts, samples of infant and specialised formula milk products, or invitations to seminars, conferences, and events.

The mentioned research shows that 22% of women in South Africa received recommendations from health professionals to use a formula product.

As described in this report, unrelenting and multi-faceted marketing aims to persuade families, health professionals, and wider society of the need for formula milk products, undermining child health and development.

Of course, although sponsored or paid advertising is beneficial to journals in terms of revenue, according to a commentary co-written by Helen Clark and Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus of the WHO, formula milk marketing represents one of the most underappreciated risks to the health of infants and children.

Clark and Ghebreyesus stress that while exclusive breastfeeding for babies six months and younger has increased only marginally over the past two decades, the sales of formula milk have nearly doubled. “Scaling up breastfeeding could prevent an estimated 800,000 deaths of children under the age of five and 20,000 breast cancer deaths among mothers each year,” they say in the commentary.

As mentioned earlier, according to the research published on BMJ Global Health in November 2021, what many journals are doing by accepting sponsorships to promote infant formula as a substitute for breast milk is incorrect because it violates the International Code of Marketing of Breast milk Substitutes, which WHO translated.

A mother testing the tempreture of her baby’s bottle on her wrist. Image: Supplied

Advertising, not only in journals but also on TV, radio, or newspapers, can be a powerful tool for advertisers because it can influence consumer decisions. In fact, advertisement material can be personalised to relate to consumers’ feelings and personal situations, which means that they have a greater chance to be drawn to whichever product is advertised, regardless of its impact on individuals; consumers make decisions that may be harmful to them without realising it.

Indeed, an article published by Forbes explains that misleading ads are unethical, and they’re often illegal, too. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulates truth in advertising, and it expects marketers to make accurate statements in their advertising campaigns, back claims with scientific evidence whenever possible, and be transparent about negative features.

Yet, in the hope to increase sales, marketers frequently accentuate the positive aspects of their products while downplaying the harmful elements. Unfortunately, in these types of advertising, the line between ethical and unethical often becomes a little blurry.

The paper also explains how companies that advertise and promote their breast milk substitutes in ways that contradict the International Code of Marketing of Breast milk Substitutes violate the rights of children to be fed in the best possible way and for mothers to make informed decisions about infant feeding.

Breastfeeding vs formula milk

According to WHO, breastfeeding is one of the most effective ways to ensure child health and survival. However, nearly two out of three infants are not exclusively breastfed for the recommended six months.

The 2016 South African Demographic Health Survey shows that breastfeeding is initiated among two-thirds of children within one hour of birth and that only 32% of infants under the age of six months are exclusively breastfed.

In addition, findings of a cross-country exploratory study published in the British Dental Journal in February 2020, and that investigate the labelling, energy, carbohydrate, and sugar content of formula milk products marketed for infants, suggest that globally, infant formula products are higher in carbohydrates, sugar, and lactose than breast milk.

Such information should be clearly labelled — but based on the findings of this study, mandatory regulation of sugar content in formula products is still needed with clear front-of-package (FOP) nutrition information to help consumers choose the healthy option for their infants.

“Consumption of excess sugar during infancy can increase the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including obesity, diabetes and dental caries. The reduction of sugar consumption has been high on the global public health agenda. Although most infants are fed formula milk products in addition to, or instead of, breast milk (with only 38% exclusively breastfed), the sugar content of these products is often not included in sugar reduction strategies,” says the researchers in the above-mentioned study.

The WHO further states that breast milk is the ideal food for infants: it is safe, clean, and contains antibodies that help protect against many common childhood illnesses. Indeed, breast milk provides all of the energy and nutrients that an infant requires during the first few months of life, and it continues to provide up to half or more of a child’s nutritional needs during the second half of the first year and up to one-third of a child’s nutritional needs during the second year. Breastfed children are less likely to be overweight or obese as adults and are less likely to develop diabetes later in life; also, the mothers have a lower risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

Health and medical journals are used mainly by health professionals who are trusted by the general public, and it is common in communities for people to trust their doctors and nurses more than anyone else to provide health-related information and assist with decision-making.

So what happens when medical journals mislead health care professionals, especially doctors and nurses? This could potentially mean that health professionals inadvertently provide false information to their patients.

Telling the truth

Article 7.2 of the Code states that “Information provided by manufacturers and distributors to health professionals regarding products within the scope of this Code should be restricted to scientific and factual matters, and such information should not imply or create a belief that bottle-feeding is equivalent or superior to breastfeeding”.

It is critical that healthcare workers are not misled because they are trusted figures in their communities.

“The aggressive marketing of breast milk substitutes, especially through health professionals that parents trust for nutrition and health advice, is a major barrier to improving newborn and child health worldwide,” said Francesco Branca, Director of the WHO’s Department of Nutrition and Food Safety in an article published by the WHO on 27 May 2020.

He added that “Health care systems must act to boost parent’s confidence in breastfeeding without industry influence so that children don’t miss out on its lifesaving benefits.”

Insinuating that formula is similar to mother’s milk may influence health professionals’ perceptions and infant feeding advice. Article 10 of the EU Regulation 609 of 2013 also states that “The labelling, presentation, and advertising of infant formula and follow-on formula shall be designed so as not to discourage breastfeeding. And secondly, the labelling, presentation, and advertising of infant formula, and the labelling of follow-on formula shall not include pictures of infants, or other pictures or text which may idealise the use of such formulae.”

However, in many countries, front-of-pack labelling (FOPL) is still a problem, and mothers are not given all of the information they need to know about formulas. And some of the labels are difficult to comprehend. Therefore, instead of using children’s pictures on the FOP labelling of formula milk, it is critical to use a traffic light FOPL warning system, which is already being introduced and used in countries such as Chile.

South Africa is also in the process of implementing the FOPL, as explained by Health-e in a 2019 article. SA National Department of Health Director of Nutrition Lynn Moeng says that current labels on food aren’t consumer-friendly: “Most consumers can’t interpret them, and it doesn’t help them to make healthy choices. So there’s been a move globally for countries to come up with labels that consumers will see easier and will be able to interpret to assist them to make healthier choices”.

Dangers of promoting breast milk substitutes

The dangers of promoting breast milk substitutes are severe in low- and middle-income nations, where healthcare is scarce and malnutrition is common. Breast milk substitutes are neither economical nor sustainable for most people in low- and middle-income countries, increasing infant morbidity and mortality.

Given these problems, the COI commentary on maternal and child health states that scientific journals have a professional and ethical obligation to implement additional safeguards to guarantee that their brands are not associated with false advertising claims and alert readers about the severe hazards associated with inadequate breastfeeding.

This commentary notes that such advertisements, the companies that place them and the journals taking their money exhibit a complete disregard for global consensus on avoiding conflicts of interest in global health in the marketing of breast milk substitutes and contribute significantly to undermining support for breastfeeding among health and scientific opinion leaders, which, by extension, undermines breastfeeding in the general population.

In 2014, the International Society for Social Pediatrics & Child Health published a position statement calling for the ending of all sponsorship from manufacturers of commercial formula products to pediatric associations. In 2019, the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health stated that it would no longer accept funding from formula milk companies. In 2019, the British Medical Journal and its affiliated publications committed to no longer receiving funding from breast milk substitute manufacturers. Lake et al (2019) made a call to South African health and nutrition journals to follow suit.

Although some journals may need to generate revenue through advertising, health experts urge editors to establish clear policies governing what types of advertisements are permitted, guided by medical and public health implications and national and international policies. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.