RECONCILIATION OP-ED

Desmond Tutu’s legacy and the TRC: Can truth reconcile a divided nation?

Perhaps the most important lesson promulgated by the TRC is that ‘both sides in the Struggle did horrible things’. If one accepted this view, one might have come to see the Struggle over apartheid as one of ‘pretty good good’ against ‘pretty bad bad’, not as absolute good versus infinite evil.

The State of the Nation Address for 2022 will now be delivered on the back of the stinging attack on the Constitution and the judiciary by Minister of Tourism, Lindiwe Sisulu. It will also be delivered in the aftermath of the insurrection in KwaZulu-Natal in July 2021, an event that dealt a heavy blow to South Africa’s democracy.

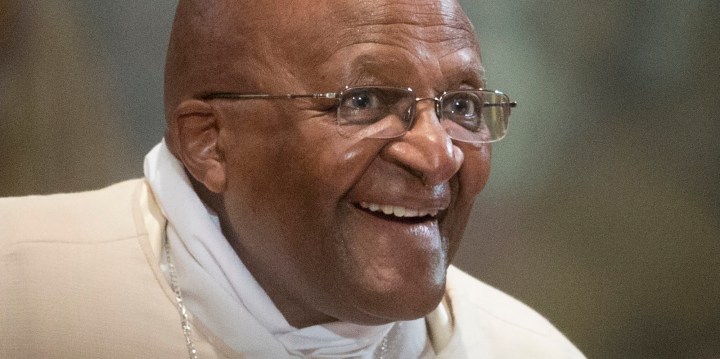

After the recent passing of South Africa’s moral compass, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, it will be sobering to consider the state of reconciliation in South Africa in which our democracy was to be embedded. For Tutu, who was the Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the creation of a collective memory that is now systematically being eroded by the types of attacks like that of Sisulu, coupled with the unbridled populism of the EFF, was one of the key objectives.

Initiated in 1995, South Africa’s TRC and the process it commanded laboured to create a collective memory for South Africa (“truth”) under the hope that producing a documentary record of the country’s apartheid past would contribute to “reconciliation”. This bold undertaking to mould the country’s fate consumed much of the country’s energy during the initial years of its transition to democracy. Tutu led this effort.

How successful was the truth and reconciliation process in South Africa? Answering this question is important since South Africa is regularly held up around the world as a model for transitional regimes attempting to overcome their conflictual pasts. If “truth” “worked” in South Africa, perhaps it can work elsewhere.

Co-author of this article James L Gibson’s book, Overcoming Apartheid (2004) (the second entry in his “overcoming trilogy” of books on South Africa’s transition) provides what is still the most rigorous and thorough account of the success of South Africa’s efforts. Based on lengthy interviews with thousands of ordinary South Africans, the book specifically asks whether truth can lead to reconciliation.

South Africans themselves are not sanguine that “truth” or “reconciliation” was in fact produced by the process. Many complain that exposing the misdeeds of both the apartheid government and the liberation forces exacerbated racial tensions in the country. Some vehemently reject the conjecture that “truth” ever leads to reconciliation, claiming instead that uncovering the details about the horrific events of the past only embitters people, making them far less willing to coexist together.

In what is probably the most comprehensive study conducted of the effectiveness of the truth and reconciliation process, Gibson concluded that the process was indeed successful at producing a collective memory that most South Africans embrace, and that this collective memory has contributed to reconciliation.

For instance, vast majorities of every racial group in South Africa — including whites — believe that apartheid as implemented in their country was a crime against humanity. Most importantly, those who accept the TRC’s truth about the past are more likely to embrace reconciliation, to be politically and racially tolerant, to hold human rights in high regard, and to accept the legitimacy of the new political dispensation in the country. This is the first systematic evidence ever assembled that a truth process has indeed accomplished its goals.

How is it that the truth and reconciliation process had such a salutary effect? Perhaps the most important lesson promulgated by the TRC is that “both sides in the Struggle did horrible things”. If one accepted this view, one might have come to see the Struggle over apartheid as one of “pretty good good” against “pretty bad bad”, not as absolute good versus infinite evil.

To reconcile with infinite evil is difficult; it is easier to reconcile with bad that is not entirely evil. Because all sides did horrible things during the Struggle, all sides are compromised to some degree, and legitimacy therefore adheres to the complaints of one’s enemies about abuses. Once one concedes that the other side has legitimate grievances, it becomes easier to accept their claims and ultimately to accept the new political dispensation.

South Africa’s truth process had other characteristics contributing to its success. Because the process was open, humanised and procedurally fair, the TRC was able to penetrate the consciousness of all segments of the South African populace with its message. Furthermore, the lack of legalistic proceedings made the hearings more accessible to ordinary people.

Finally, Tutu and Mandela were no doubt instrumental in getting people to accept the TRC’s collective memory and therefore to get on with reconciliation. Tutu’s message of forgiveness, though irritating to many, set a compelling frame of reference for understanding the atrocities uncovered.

Mandela’s constant and insistent calls for reconciliation, coupled with his willingness to accept the findings of the TRC (even when the ANC did not), were surely persuasive for many South Africans. The two giants of the anti-apartheid struggle defused and delegitimised much of the potential criticism of the truth and reconciliation process.

Truth may not inevitably lead to reconciliation. A different truth process might well have produced an entirely different outcome. Obviously, the truth that can be constructed is constrained to some degree by reality; not any collective memory can be fabricated out of any given set of historical circumstances.

But truth commissions can seek to act impartially, allocating blame wherever it may lie, or truth commissions can engage in a form of “victor’s justice” in which the victors are held to lower human rights standards than the vanquished. The South African TRC sought the path of impartiality (dubbed “poisonous evenhandedness” by its critics), casting the net of blame widely.

The lesson of South Africa’s TRC is that holding all parties to the same human rights standards creates a framework of ambiguity about good and evil within which enemies can reconcile with each other.

“The Arch” was certainly not the only contributor to the success of South Africa’s truth and reconciliation process. But throughout the transitional period, Tutu stood as a beacon of reconciliation for all South Africans. And few would contest the view that, without Desmond Tutu, the commission and the country would have been much worse off. DM

James L Gibson is the Sidney W Souers Professor of Government at Washington University in St Louis. In addition, he is an Extraordinary Professor in the Political Science Department at Stellenbosch University. His book Overcoming Apartheid: Can Truth Reconcile a Divided Nation?, published by the Russell Sage Foundation (2004), is perhaps the most authoritative account published of whether and how a truth commission can succeed.

Amanda Gouws is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Stellenbosch University. She is the co-author with James L Gibson of the award-winning Overcoming Intolerance in South Africa: Experiments in Democratic Persuasion (Cambridge University Press) (2003).

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9041″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.