REFLECTION

My dad, Dr Mac, taught me what it means to live a life that matters

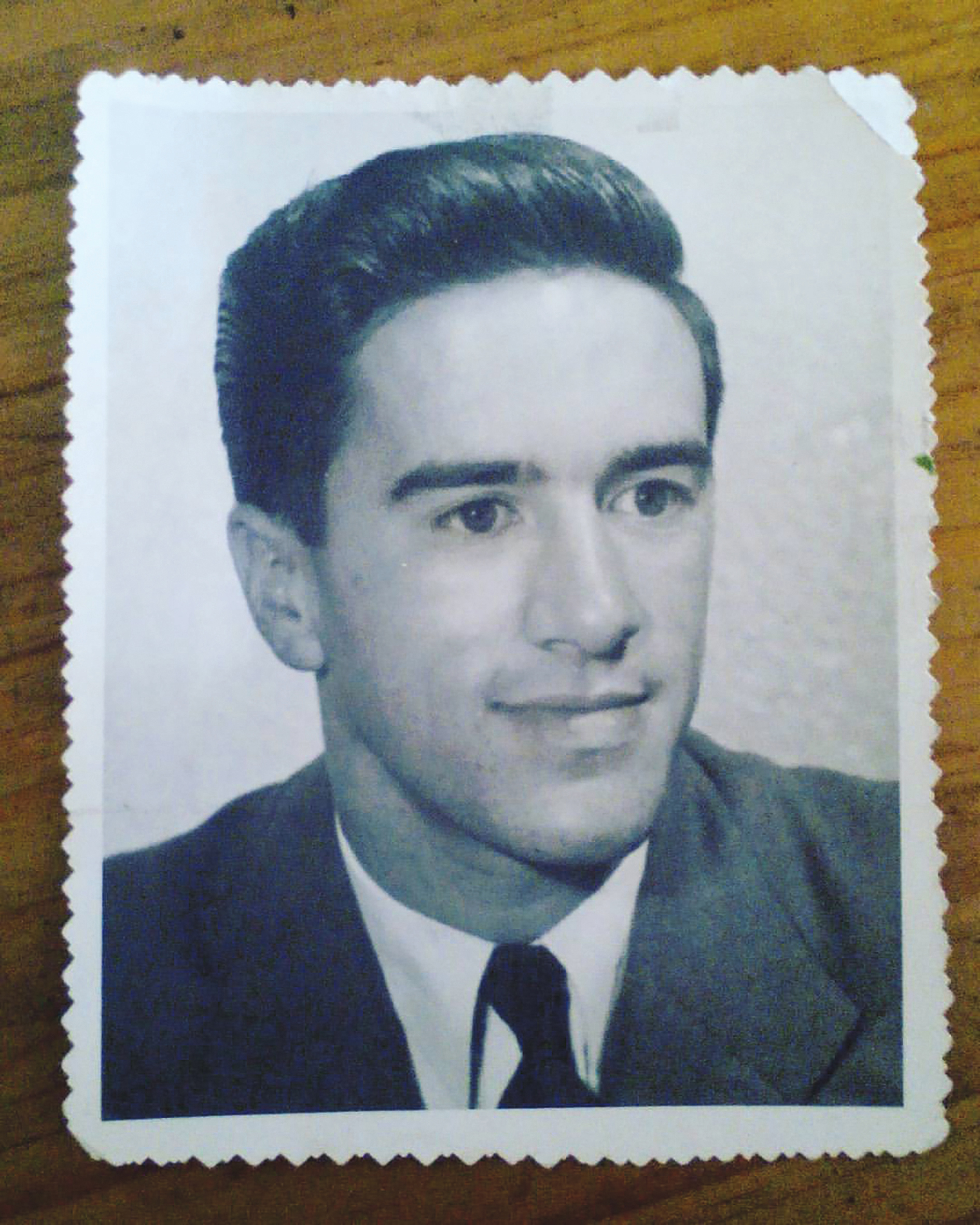

My father lived 20 more years than the Bible’s allotted three score years and ten, and reluctantly retired from his popular diabetic practice at the Netcare Parklands Hospital in Durban, four years ago at the age of 86. Now that the aftershock of his departure is slowly easing, I thought it fitting to reflect on his life and legacy.

Two months ago, on 25 October, my father Dr Leslie Ivan Robertson, fondly known as Dr Mac, DocMac, Mac, Papa and Dad, ended his long journey on Earth. Fortified with his two Pfizer vaccines, he managed to dodge Alpha and Delta, but not his final nemesis, a stroke.

He flew away just before the Highveld sun spilled its dawn palette of pink, orange and gold on an array of cumulonimbus clouds that hung over the Unitas Hospital in Centurion. In the high care ward at Unitas, where he spent the last five days of his life, my father was treated by nurses and doctors who would have made him proud if he was cognisant. Because they cared. And treated their patients with dignity and compassion. Just like he did his entire life as a medical practitioner.

My father lived 20 more years than the Bible’s allotted three score years and ten, and reluctantly retired from his popular diabetic practice at the Netcare Parklands Hospital in Durban, four years ago at the age of 86. Now that the aftershock of his departure is slowly easing, I thought it fitting to reflect on his life and legacy, which, like many South African lives and legacies, do not make our headlines because they are not what we journalists deem newsworthy enough, big enough or nationally impactful enough to warrant telling in our first drafts of history.

Our first drafts of history, which tend to focus largely on the wealthy, famous, corrupt, criminal, crooked and powerful, are all the poorer for whom and what they choose to ignore. Sometimes the oral stories of ordinary folk and the narratives of poets, novelists and artists are that much richer, nuanced, complex, less Manichean in their cast of characters and, dare I say, truer to the essence of who we are and who we can be as people because they cast their gaze beyond the loud, belligerent minority of the worst of us.

This recollection of my father’s life is not told just by me, one of the flawed first drafters of history, but in collaboration with him, through his own oral and written reflections, other family members, colleagues and patients whose lives he affected.

Born on 20 April 1931 to Maude and William Robertson, at 40 Chatham Road, Salt River, Cape Town, Leslie Ivan Robertson was nicknamed Mac by his cousins after a character in a comic strip called Mac and Tillie the Toiler. As people often spelt his name the feminine way (Lesley), he preferred to be called Mac throughout his life.

Like many in their neighbourhood, the family was very poor. They did not have a car or a fridge and only had use of an outside toilet. Maude died in early 1939, when Mac was seven years old. She had pulmonary tuberculosis for which there was at that time no cure. After her death, he, his two brothers and father lived at first with his aunt and uncle (who eventually became white and shunned the rest of the coloured side of the family) and later with another aunt and then his granny. During the time he spent with aunt number two, another eight members of his close family also died of tuberculosis. He recalled sharing a bed with his cousin and waking up to find him dead. It was this dreaded disease that robbed him of his mother and so many other family members that made Mac solemnly promise to work for a cure when he grew up.

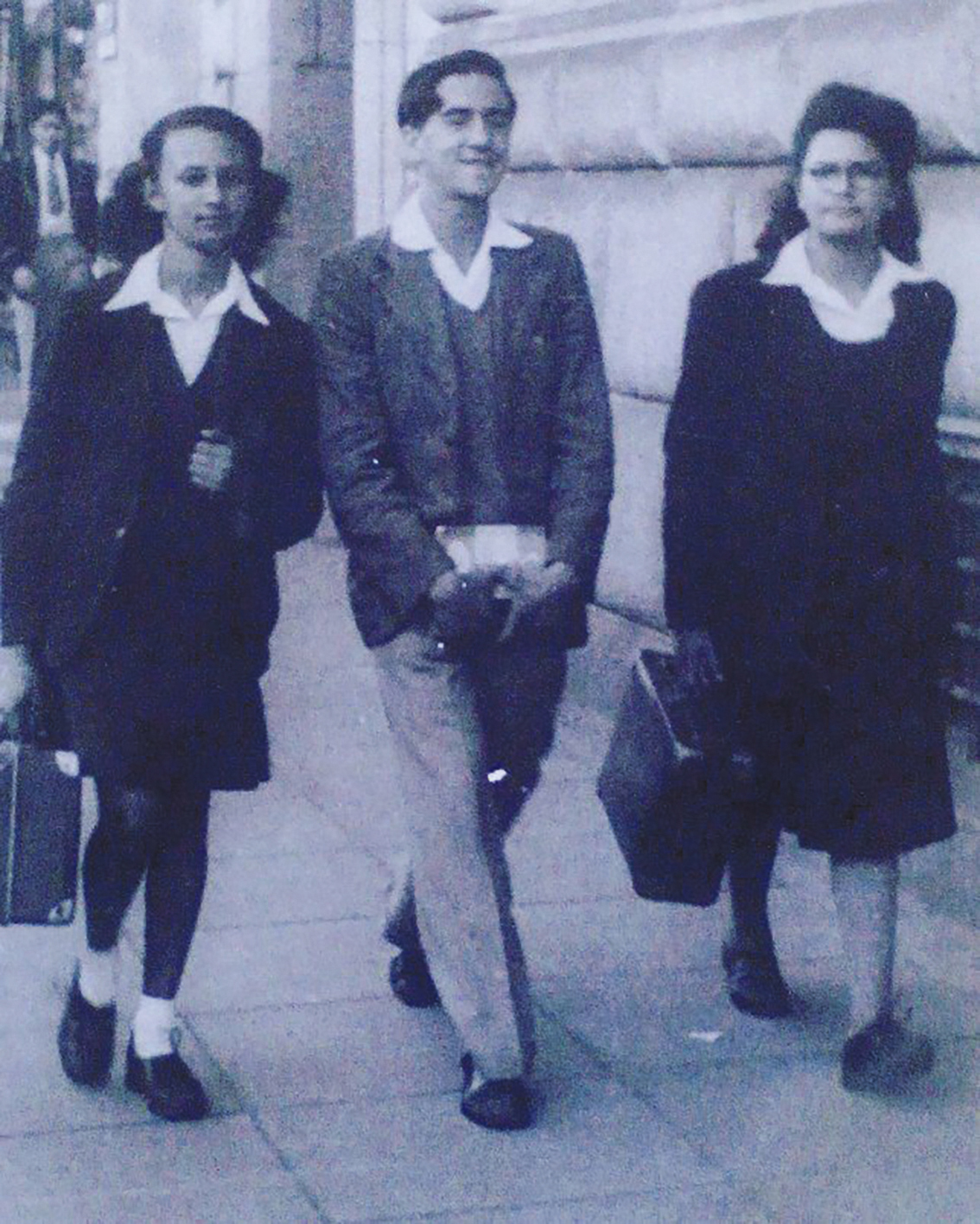

Mac’s early education was at Wesley Practising School and then Trafalgar High School, where he had the privilege of being taught by Ben Kies, an anti-Stalinist and anti-colonialist left-wing political activist and theorist, teacher and advocate. Mac’s greatest memory of Kies at Trafalgar High was an English exercise in the art of empathy that stymied his entire class. Kies told them to write three pages explaining the concept of colour to someone who was born blind.

It was not Kies, but Mac’s working-class father who urged him to become a doctor. As they could not afford the fees, he had to work all his holidays in the furniture factories where his father, a French polisher, was employed. He also served as a wine waiter at the posh New Orleans Club for many weekends and he was paid to paint lines on the legs of young women from his neighbourhood who could not afford stockings.

Mac studied medicine at the University of Cape Town (UCT), where he and the nine other “brown” students were told by the Dean of Medicine that if they saw a white corpse when attending a post mortem in the mortuary, they should remove themselves and stand at the back. During the first week of their third year, they were also told to sit at the back of the A5 main lecture theatre and to leave the room if the patient wheeled in for diagnosis was white. What this meant was UCT’s racist policies led to my father and his nine fellow melanin-enriched medical students missing out on clinical medicine teaching of certain diseases.

After graduating, Mac applied to but was turned down at the only hospital in Cape Town that would accept coloured doctors, but he was accepted at McCord Zulu Hospital in Durban, where he had spent a working holiday at the end of his fourth year of study two years earlier. One of Mac’s most vivid memories of McCord was treating the then leader of the ANC and Nobel Peace Prize winner Chief Albert Luthuli, for a coronary attack, a disease which at that stage had not been known to afflict black patients. Mac was summoned to assist Chief Luthuli by his daughter Hilda (Thandeka), who was a staff nurse in the adult male section. Even though he was a junior in the paediatric section, she did not trust any of the other doctors to treat her father.

It was at McCord that Mac also befriended nursing sister Amy Weaich, who he helped flee the country via Zambia after her anti-apartheid activist husband, Basil Weaich, was arrested by the Security Branch. I was an infant when this happened and only came to know of this part of my father’s life when Amy shared this story at his memorial service.

She recalled: “Many people were not aware of the support Mac gave not only to me but many others. This was very risky for him and his GP practice and his family but he continued to support me and to help me leave the country. Once I was in Zambia I could not communicate with him anymore as the Special Branch was watching the mail of all my friends. Many of those who supported me were intimidated by the police.”

After a few years of learning to be a paediatrician at McCord, Mac started a medical practice in the Durban suburb of Sydenham. Quite soon after this he was able to fulfill his promise to help save people suffering from tuberculosis when he became a part-time medical superintendent at the FOSA TB settlement. By now there were drugs (very cheap drugs) that cured just about all cases of this disease, leaving him with the sad thought that his mom and half his cousins and his wife’s family would still have been alive if the drugs had been found earlier. At his practice, Mac became an expert in sexual medicine (both he and my mother Barbara would run sex counselling workshops at his surgery) and he helped improve many a patient’s quality of life by prescribing that famous blue pill.

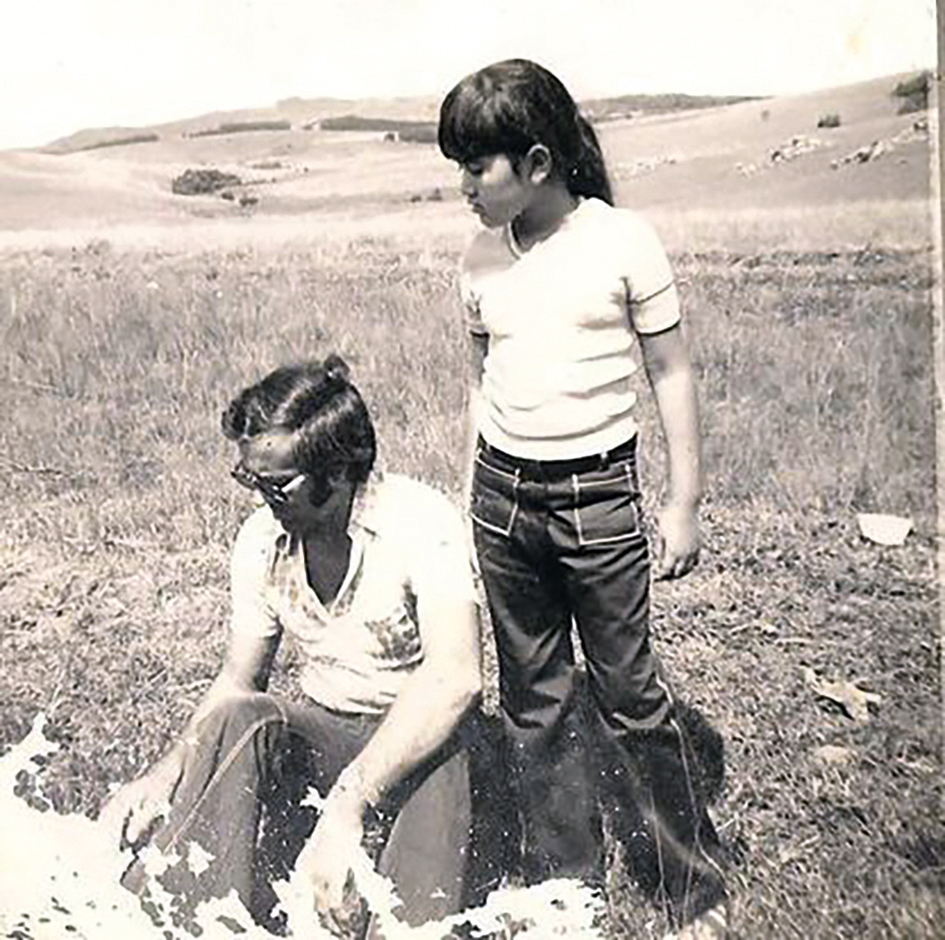

Mac and my mother, Barbara, on one of his many trips to Malaysia. (Photo: Robertson family collection)

In 1969, Mac was asked to work in the Diabetic Unit of the Addington Hospital, and he spent the next 30 years there, eventually as the senior doctor in charge. He also participated in numerous research projects designed to help diabetic sufferers and travelled to many parts of the world to learn more about the disease, which by the year 2025 will affect more than 3 million South Africans.

Always uncompromisingly himself, even when he came across as blunt, stubborn and rude as a curmudgeonly bull in a China shop, Mac was seen as a saviour by his many patients in Sydenham and the greater Durban area who he healed, whose babies he helped enter in this world, whose lives he saved. This story told by one of his patients, Gaynor Bowes, explains why:

“I was little when Doctor Mac paid a visit to our home as my sister wasn’t well. My mom complained of a headache and he took a look at her as well. He said this doesn’t look good and a few hours later had her admitted to Wentworth Hospital. She’d had a brain haemorrhage at age 30.

“She was taken to theatre the next day. Doctor was on his way out that evening when the hospital called to say his patient (my mom) had died. He dropped everything and rushed to the hospital. My mom was lying on the gurney ready for the morgue. He removed a plug from the suture site and a drop of blood fell, so he decided to resuscitate her, much to the disbelief of the nurses as she had been dead more than 35 minutes by that time.

“His words were: ‘Where there’s blood there’s life and she deserves the chance to live.’ Mom was resuscitated and lived till 77, all faculties intact, save for an unsteady gait at times and a slur (but still able to swear like a trooper).

“The other amazing thing that many don’t know is that for years Doc treated our family free of charge as my father left soon after and my mom was unable to work.”

Travels with dad (from left): DocMac with his four children – Peter, Mike, Dawn and Heather – on holiday in Vietnam in 2015, a year after his wife died. (Photo: Robertson family collection)

Stories like these shared by patients, colleagues and friends of my father after his death, make me realise what it means to live a life that matters. A life of passion and service to others, a life of love and laughter despite the innumerable hurdles and disasters that get flung in your path.

I will remember my father not as a saviour or a healer, but just as Dad. Dad who relished beating me at Scrabble and who shouted at my driving. Dad who taught me how to sandpaper with the grain like his dad taught him to do. Dad who gave me my first typewriter and my first giant Collins Dictionary. Dad who woke me up in the morning to go running and swimming at Point Road Beach when I was a child, who taught me how to keep going by not looking at the top of a hill when running or walking, to just focus on your feet, one step at a time. Dad who taught me how to climb down kelp to dive for crayfish and perlemoen in the freezing Cape Point sea, Dad who stood behind me during my DM168 online meetings, fascinated by how this newspaper was made at home during a pandemic. Dad who loved to travel and when I was 14, took me on my first epic tour of South East Asia, opening my mind to a world of mystique, spirituality, a greater humanity and adventure. Dad whose naartjie, lemon and lime trees in our garden and flowering orchids on the stoep outside his room, make my heart smile and ache. DM168

(This reflection was written with a lot of help from my dad through his own autobiographical writing and oral stories. At last you made it into DM168 Dad!)

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a lovely memory of a man that lived a full life and gave back everything that life granted him.

Aah Heather. Lovely tribute to a special person. He must have made a difference to so many lives.

Thank you so very much, Ms Robertson, for your lovely tribute to your wonderful father, who made a significant difference to so many. It is certainly inspiring to read about his very full and well lived life and career. Thank you so much for sharing his story.

I am certainly enjoying this series of tributes to fathers, it is certainly uplifting and inspirational. Thank you very much, Daily Maverick for this series! I also was moved by Nik Rabinowitz’s recent tribute to his father.

Lovely Heather. What a gift your Dad was to many. This series has made me reflect on my Dad in a inspiring way.

A special tribute to an obviously special dad and doctor- makes me feel humble as a colleague to read about such a caring , compassionate ” old fashioned” doctor- would that we still had more of the same.

Insightful, inspiring, heartfelt and a reminder of how much has changed in our country – and what living a life of service truly means. Thank you.

What a moving tribute. Thank you Heather for a special insight into the life of an unsung hero whose impact on the lives in his reach was significant. This touched me deeply.