LOCALISATION OP-ED

Capitalism’s recalibration: From globalisation to deglobalisation to onshoring

The resurgent interest in – and fear of – ‘localisation’ (or ‘onshoring’ of productive capacity) is at the core of an ideological controversy.

A few years after a prior era of financialised globalisation ended in tears, amid banking crashes and the Great Depression, leading British economist John Maynard Keynes concluded in a 1933 Yale Review essay: “Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel – these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.”

On the one hand, international travel was again disrupted thanks to Covid-19’s Omicron variant, in a manner that once again reeked of the Global North’s malevolence, just like its posture at last month’s Glasgow climate summit and in the World Trade Organization’s vaccine debates. On top of that, South Africa faces the likelihood of climate taxes on air travel – due to our long distance from wealthier tourists’ homes – which will leave our tourism and hospitality sector even more at a disadvantage, unless a climate justice deal or some other breakthrough is achieved.

And this suffering is relatively minor, compared with a broader capitalist recalibration here, again demonstrating that – especially since 1971 when gold was delinked from the US dollar – South Africa sinks faster during global economic turbulence than nearly any other country.

Today, resurgent interest in – and fear of – “localisation” (also termed the “onshoring” of productive capacity) is at the core of an ideological controversy that urgently requires some additional empirical information. When two eloquent Centre for Development and Enterprise analysts – Ann Bernstein and Anthony Altbeker – are joined by influential Business Day columnist Peter Bruce to denounce the added costs and inefficiencies associated with Trade and Industry Minister Ebrahim Patel’s strategy to substitute homegrown goods for imports, this is to be expected.

Minister of Trade and Industry Ebrahim Patel’s crony capitalist philosophy is also abundantly evident in ecologically unsound fast-tracking. (Photo: Gallo Images/Phill Makagoe)

Unexpected, however, is these critics’ complete silence when it comes to acknowledging real-world factors: declining global and local trade/GDP ratios for more than a dozen years, chaotic global value chains, rising shipping costs and logistics crises, the need to strengthen coherent internal economic linkages and regenerate manufacturing employment, imminent climate sanctions on exports, and our trade partners’ worsening protectionism. To be sure, neither has Patel, though at least Cyril Ramaphosa seems to have his finger on the pulse of some of them.

A localisation winner

The most obvious case justifying onshoring of production, requiring little explanation given the context of ongoing Covid pandemic and the Global North’s grip on vaccine intellectual property (IP), is making medicines locally. Both Ramaphosa and Patel deserve credit here, for in spite of their initial failures at vaccine acquisition, they joined the Indian government in October 2020 to demand an IP waiver, to assure wider production of Covid-19 vaccines and treatment.

The already sizzling-hot World Trade Organization debate will continue, with hopes that Angela Merkel’s dogmatic opposition to Ramaphosa’s proposal will be reversed by her Social Democrat successor Olaf Scholz, now that Boris Johnson’s humiliation at the Glasgow Climate Summit lowers his status when he defends status quo “vaccine apartheid”.

But this crucial new fight against global capital gives us reason to consider a prior case of localisation, starting 20 years ago when similar waivers were granted at the WTO Doha summit to fight AIDS. The generic versions of antiretroviral drugs – made here by Aspen – were then provided free in the public health sector.

This is the main success story of deglobalising capital, through ending the tyranny of Global North intellectual property: a typical patient’s $15,000/year bill shrunk to less than $100 for generic manufacturing costs, allowing the expansion of treatment from a few thousand rich people living with HIV in the early 2000s to seven million at peak.

The globalisation of people – i.e. activism by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power in the US and similar advocacy groups across Europe, Médecins Sans Frontières, Oxfam and others, responding to South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign – was pitted against the typical prerogatives associated with the globalisation of capital, and the people won.

South Africa’s life expectancy soared from 52 in 2005 to 65 in 2019 before Covid-19 reversed the progress.

President Cyril Ramaphosa deserves credit for joining the Indian government in October 2020 to demand an intellectual property waiver. (Photo: EPA-EFE/Maja Hitij/Pool)

Organic deglobalisation

Starting in 2008 – coinciding with the world financial meltdown – the three core economic measures of globalisation went into reverse: trade/GDP, Foreign Direct Investment/GDP and cross-border financial flows/GDP.

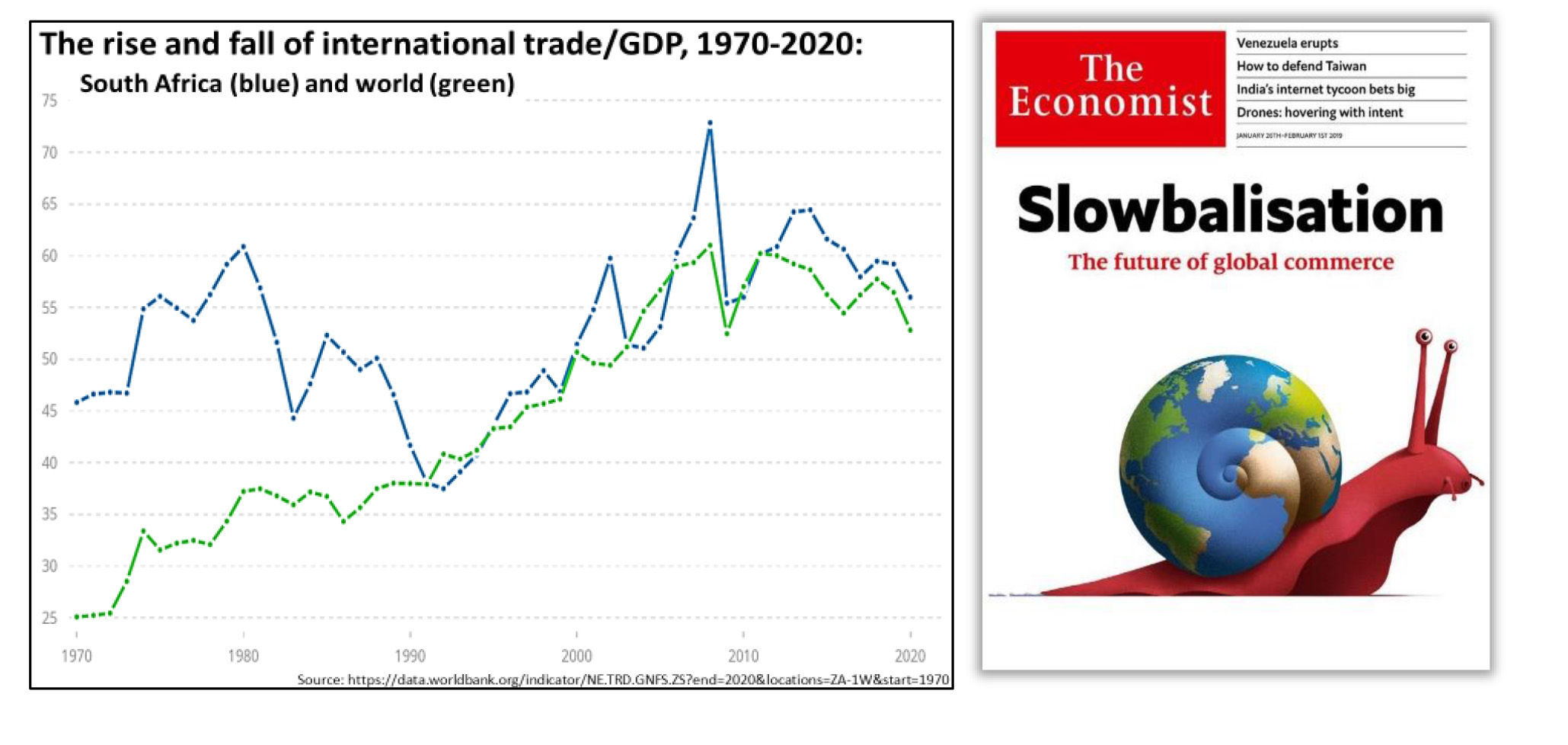

The global trade ratio is most commonly cited, and fell from a 2008 peak of 61% to 53% in 2020. South African trade fell further, from 73% in 2009 to 56% in 2020.

Both will rebound somewhat this year given the post-2020 bounce-back. But compared with the prior era, during the meteoric rise of globalisation (from 1991 when both global and South African trade/GDP ratios were just 38%), the past dozen years represent a distinct pause, nicknamed deglobalisation, or in The Economist’s lingo, the “Gated Globe” and “Slowbalisation”.

And for good reason; as in the 1930s, corporates and banks had overextended. As a result, there has been a profound correction, in part due to the natural creative destruction of a system which – thanks mainly to Chinese productivity – caused massive global manufacturing overcapacity.

The excesses within global value chains (GVCs) didn’t help, for as McKinsey remarked in 2019, “a smaller share of the goods rolling off the world’s assembly lines is now traded across borders. Between 2007 and 2017, exports declined from 28.1% to 22.5% of gross output in goods-producing value chains”.

The firm’s follow-up report in 2020 warned: “Intricate production networks were designed for efficiency, cost and proximity to markets but not necessarily for transparency or resilience. Now they are operating in a world where disruptions are regular occurrences. Averaging across industries, companies can now expect supply chain disruptions lasting a month or longer to occur every 3.7 years, and the most severe events take a major financial toll.”

With US President Joe Biden refusing to undo the trade restrictions that his predecessor Donald Trump imposed, we can anticipate anti-trade sentiment to continue. (Photo: EPA-EFE/Jim Lo Scalzo)

The European Central Bank was correct to worry, in 2020, that: “For the world economy in the short term, GVCs could amplify the decline in imports and exports occurring through direct linkages (i.e. traditional trade) by around 25%.”

Container transport chaos

A major cause of the immediate crises across so many value chains is the chaotic state of world shipping. From 2008 to 2020, the ever-larger container vessels’ scale economies had lowered maritime emissions somewhat, but it was the role of trade stagnation in cutting bunker fuel emissions during that period that was most helpful to slowing the climate crisis.

However, since the Covid-lockdown low point of April 2020, soaring shipping costs – measured by the Baltic Dry Index – have revealed another good reason for localisation, as artificially imported inflation follows from that index’s rise, from within a 300-700 band during most of the last decade, to more than 6,000 earlier this year, with the index still above 2,500 today.

Another reason for the price-hiking panic was vulnerability in the system exposed by the grounding of the Ever Given, a massive Taiwanese-based container ship. Stuck in the Suez Canal in March, Ever Given blocked 13% of world trade for a week. The vessel’s deep (16m) draught – required to carry 20,000 containers – is so large, it doesn’t fit inside the main South African harbours (aside from faraway Saldanha).

Our ports’ physical limitations are one reason this economy can’t take advantage of mega-ships. But worsening operational paralysis is another, for although Durban is sub-Saharan Africa’s busiest container port, the World Bank ranks it the world’s third-least efficient major container port out of 364.

And that was before Transnet declared force majeure there three times: a fire in Maydon Wharf in October, preceded by July’s ransomware attack, which came shortly after the unprecedented looting spree that also temporarily shut harbour operations. Moreover, Transnet’s rail and pipeline networks have suffered such spectacular failures – including widespread theft and fuel bunkering – in recent months and years, that the entire notion of “network infrastructure” linking South Africa to the rest of the world needs a rethink.

Factors supporting localisation

Instead of importing so many goods at a time when the climate crisis requires far less CO2-intensive shipping, “import-substitution” technology does offer hope.

There is, first, the prospect of building upon regional scale economies to re-industrialise, via the African Continental Free Trade Agreement. Vitally needed backward and forward supply and demand linkages to other parts of the local economy require nurturing, in the process reducing South Africa’s extremely dangerous level of unemployment before another July-style socioeconomic powder keg explodes.

And some new technologies can help, not hinder the process. For example, “as a result of widespread implementation of 3D printing” for a huge variety of manufactured goods, economists Avner Ben-Ner and Enno Siemsen suggest that “global will turn local; mega (factories, ships, malls) will become mini; long supply chains will shrink”.

Indeed, the factors that drove globalisation – massive Asian scale economies, pollution (especially climate-destructive) externalities, and the labour repression that together made China such a source of high-profit production these last decades – will run up against not only local 3D printers but also both ever-higher shipping costs and climate taxes.

The latter – in the form of a “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism” (CBAM) imposed by Western importers on South African exports – could be decisive, with Ramaphosa expressing his own concern last month in a presidential letter advocating a low-carbon economy and just transition for affected workers and communities:

A protest at Hobie Beach in Gqeberha against Shell’s seismic blasting on the West Coast. (Photo: Deon Ferreira)

“As our trading partners pursue the goal of net-zero carbon emissions, they are likely to increase restrictions on the import of goods produced using carbon-intensive energy. Because so much of our industry depends on coal-generated electricity, we are likely to find that the products we export to various countries face trade barriers and, in addition, consumers in those countries may be less willing to buy our products.”

The CBAM will indeed hit South African metals and auto exports hard in 2023, especially because of fossil fuel projects still in the pipeline. Eskom’s replacement of coal will include CEO André de Ruyter’s much more potent methane-based LNG in several Mpumalanga power plants, as well as Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe’s Karpowerships that may float into three harbours.

Add to these several Chinese firms’ proposed Musina-Makhado coal-fired power plant and high-carbon metallurgical complex, which their own plans acknowledge will emit 14% of South Africa’s greenhouse gases in 2030. And now come billions of barrels worth of offshore Brulpadda gas drilling by Total, not to mention the controversial Wild Coast exploration under way by Shell, Impact Oil & Gas and Myanmar-based Silver Wave Energy.

So, climate sanctions on South African exports look certain. Perhaps because of the trade surplus from the last month’s commodity boom, Mantashe must have already discounted exports as less important than his vision of tapping South Africa’s coal and gas down to the last hydrocarbon, damn the climate and future generations.

In this fossil-addicted context, perhaps the most troubling sign is that both Eskom and Sasol aim to become yet more methane-dependent even though the main prospective source – Cabo Delgado, Mozambique (the world’s fourth-largest gas field) – is a war zone where the South African National Defence Force is currently consuming R2-billion for soldiers to defend the interests of Total, ExxonMobil, ENI and the China National Petroleum Corporation, with more such subsidies anticipated.

Given the terrible cyclone destruction in 2019 caused by higher temperatures in Mozambique Channel waters, we should be paying climate reparations to the residents, instead of sending bombs, bullets, boys and, unfortunately, body bags.

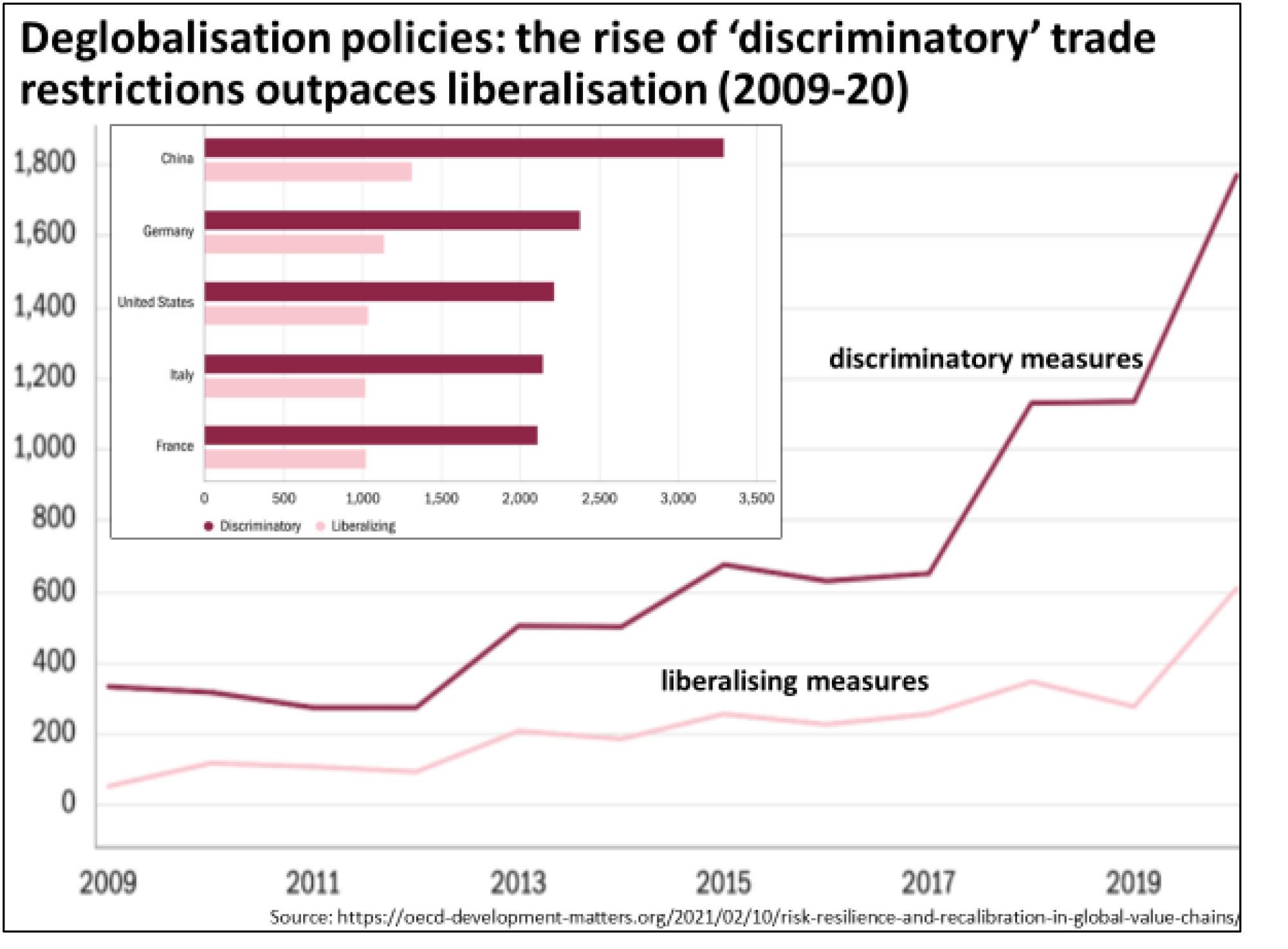

Finally, there are hostile geopolitical trends. As the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) warns, “ongoing protectionist and geopolitical trends suggest that the world is unlikely to see a return to business as usual”. With Joe Biden refusing to undo the trade restrictions that his predecessor Donald Trump imposed, partly because Biden faces extremely low popularity ratings and he dare not lose more white working-class votes in next year’s midterm election or in his 2024 re-election, we can anticipate this anti-trade sentiment to continue. Already, with Washington-Beijing tensions rising, there’s a Trumpish Sinophobia evident in Biden’s speeches.

And even more protectionist than the US are two other major South African trading partners – China and Germany – which actually imposed far more “discriminatory” than “liberalising” trade measures since 2009, according to the OECD.

Conclusion: An end to onshoring of white-elephant, high-carb industries

Onshoring more of our economy certainly carries risks, given the distortions in the local power structure, including corporate corruption. PwC ranked South Africa in 2020 as the world’s second-worst “economic crime” zone (tied with China, behind India). In contrast, our state’s politicians and bureaucrats are considered the 110th-most corrupt in the 2021 Transparency International survey.

Fraud has been evident in Patel’s own portfolio when – according to emails between Marcel Golding and Yunis Shaik – he took an in-kind bribe from eNCA, to promote a dubious Limpopo dam on the main TV news programme, in exchange for a homegrown Ellies television set-top boxes contract that would have enriched Golding. Patel’s crony capitalist philosophy is also abundantly evident in ecologically unsound fast-tracking: Durban’s destructive Cornubia UPL chemical inferno in July can in part be traced to his department’s laxity.

Moreover, who can deny that irrational localisation “lemon” strategies proliferated during apartheid, such as the long-standing coal-squeeze – followed by methane-squeeze – conducted at Sasolburg and Secunda (world’s highest greenhouse gas emissions point source). This was Nazi-era technology deployed to combat United Nations oil sanctions, but its continuation into the liberated era is surreal given that the social cost of carbon is now estimated at $3,000 per ton, making South Africa’s annual 500 megatons of combustion effectively 3.3 times more expensive than annual GDP, with Sasol the second main contributor to the damage, after Eskom.

Moreover, as Bernstein, Altbeker and Bruce point out, there are likely to be more such foolish mistakes made by a Department of Trade and Industry which, they would not disagree, often fails to properly pick winners because it hasn’t got around to full-cost accounting, including rudimentary carbon footprinting.

To illustrate, Patel continues to lavish massive subsidies (R27-billion in 2018) on what are mainly luxury-priced auto exports. This subsidy represents the single most substantive industrial policy, so Patel’s fetish for helping multinational auto corporations deserves the devastating criticism levelled by Cape Town economist Dave Kaplan.

Although a new electric vehicle is finally going to be built in South Africa, there appears to have been no concern by Patel or his predecessors dating a quarter century to Trevor Manuel and Alec Erwin, that solo-driven cars have such an enormous carbon footprint, at a time working-class public rail transport has broken down and kombis remain dangerous.

To get to a low-carb version of import substitution industrialisation, of the sort that widened manufacturing and generated 8% annual GDP growth from 1933 to 1945, during the prior deglobalisation era, a new generation of onshoring entrepreneurs will be needed.

But they will need watchdogging – hence the Climate Justice Charter under discussion in civil society and academia puts much more power in the hands of progressive labour, community, youth, feminist and environmental movements. And protest is obviously critical to changing the balance forces, such as against parliamentary slackers in Cape Town last month. A genuine just transition will come through environmental justice activist class struggle; it won’t come through backroom class-snuggle deal-making in Nedlac or technicist reforms in Treasury.

There are hopes that former German chancellor Angela Merkel’s dogmatic opposition to Cyril Ramaphosa’s intellectual protocol waiver proposal will be reversed by her successor, Olaf Scholz. (Photo: EPA-EFE/Maja Hitij/Pool)

To illustrate, in order that firms finally import-substitute, Treasury’s local carbon tax of $0.42 per ton of emissions will have to rise dramatically; Sweden’s is already $132 per ton (a price 23 times lower than it should be). If carbon pricing takes off as expected, so that South African exporters can in 2023 claim they’ve already paid the equivalent of a CBAM, a vast amount of current fossil-based energy inputs and high-emissions manufacturing will have to be replaced.

The message that anti-Shell protesters provide is encouraging: the Wild Coast shouldn’t be drilled for planet-destroying methane (and helpfully, Bruce agrees that a boycott of the firm is timely). The message needed from far-sighted business commentators – as we normally expect in work by Bernstein, Altbeker and Bruce – would incorporate climate benefits of onshoring more production, and not blatantly ignore them.

And given the turbulence of the times – shipping chaos, declining trade/GDP ratios, protectionism and geopolitical tensions – the additional benefits of reducing vulnerabilities and improving backward-forward linkages will also pay dividends, if a more coherent economy, environment and society arise from the climate-fuelled ashes of globalisation. DM/MC

Patrick Bond is professor of sociology at the University of Johannesburg.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8881″]

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider