SOCIETY

Exploring what comes after capitalism in South Africa

Is there a viable alternative to our current modern economic system?

Capitalism. Some may associate the 300-year-old economic system with globalisation, connectivity, wealth and prosperity and they would not be wrong; others may associate it with social and environmental devastation, exploitation, inequality and waste, and they too, would not be wrong.

Researcher and educator at The International Labour Research and Information Group (ILRIG), an NGO that works for labour and community movements in South and Southern Africa, Shawn Hattingh says that, in South Africa, the thought camp you find yourself in depends on class and race.

“For the ruling class (capitalists and politicians/top state officials) capitalism has been and is wonderful – they have some of the highest living standards in the world and indeed even in history,” Hattingh says.

“For the black working class (workers and the unemployed) capitalism has been an utter disaster. This class is amongst the poorest of people in the world and highly exploited. The fact that capitalism is based on the oppression of this section of society means it has no real benefit for the majority of people in the country – the black working class,” he adds.

After prominent classical economists and philosophers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx and John Maynard Keynes made names for themselves studying, theorising, applying and critiquing a political-economic system that took over 500 years to transition from feudalism in the 14th century, the “big question” that economists are now concerning themselves with is what comes after capitalism and whether there is a viable alternative to our current modern economic system?

An alternative to capitalism?

Until the turn of the century, after the Soviet political and economic model collapsed at the end of the 1980s, capitalism seemed almost invincible.

This is clear in an article titled Capitalism in History published in the Social Scientist by Irfan Habib in 1995:

“Today as the 20th century comes to a close, with the collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe and the passing away of the Soviet Union, the belief has become widespread that capitalism is the only possible present and future system of economic and social organisation.” He adds, “Even theories of ‘mixed’ or ‘welfare’ economies, or of development under state guidance and protection, which had held the ground in so much of the Third World till the other day, are regarded in influential circles as obsolete and unacceptable.”

Nearly three decades later and in light of world-altering events such as climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic, capitalism is not as invincible as once thought and there is the question of whether capitalism can afford to prevail in its current form or whether it can or should take on another shape and what that shape might look like and mean for society as a whole.

Economics professor Bradley Bordiss who has recently been awarded a PhD by the University of Witwatersrand (Wits) and has been teaching the history of economic thought at the University of Cape Town (UCT) for the last eight years says that, in order to imagine the future of capitalism, particularly in South Africa, we have to return to the past.

“The problem as I see it is that we [South African society] are stuck in a kind of 1970/1980s paradigm with this binary-thinking where we are asking ourselves which is better: communism as proposed by the soviets or laissez-faire capitalism as proposed by Thatcher and Reagan?” he says.

During the interwar period in South Africa, infrastructure like Eskom and Iscor formed, railways expanded and in 1925 the first tariff act coupled with the industrial development corporation in the 1940s started promoting South African production; in the period 1933 to 1945, South Africa was marked as the top-performing economy in the world according to Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics and Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley.

Prior to Adam Smith, mercantilists were very concerned about production and they were very concerned about having as many sectors in the economy as possible. In fact, in the period between World War 1 and World War 2, South Africa focused on national economics and relied on a strong symbiotic relationship between the state and private enterprises.

When Afrikaner nationalists — who had been undercut by British imperialism prior to the interwar period — took control of the state during the interwar period, Bordiss explains there was a push to actively form and promote Afrikaner-owned businesses like Rembrandt, Volkskas Bank, Sanlam and Santam and a push for Afrikaner political, cultural and religious organisations to buy from these Afrikaners companies.

“If you were Afrikaans in 1930, your church and your cultural organisations — everyone — would be telling you: ‘Don’t bank with Standard Bank, bank with Volkskas; don’t use Old Mutual, get your insurance from Sanlam and Santam; buy your cigarettes from Rembrandt not Paul Revere; buy your newspapers from Naspers, not the Cape Times,” says Bordiss.

“Nationalism gets a bad rep because, when we think of nationalism we think of Adolf Hitler, Donald Trump, the Afrikaner Nationalists; but nationalism is basically the idea that the purpose of government is to look after the majority.”

So what went wrong?

Bordiss says things started going wrong in South Africa around the 1970s and places part of the blame on laissez-faire capitalism.

When we talk about modern mainstream capitalism we talk about something called “laissez-faire” capitalism. Laissez-faire (which translated from the French, means let-it-happen) thinkers tend to be in favour of little to no government intervention, no tariffs, no restrictions and no regulations, as well as free movement of capital, labour and goods that can come in and out without any obstruction. This is almost the opposite of a model known as “mercantilism”.

Bordiss, who is a supporter of national economics and mercantilism, explains that mercantilists concern themselves with the nation and understand that the nation and its private capital works in alliance with the government. This is something that laissez-faire capitalism does not understand.

“The idea of laissez-faire is that, if you’re a productive company, you can compete on the international stage and you will do well. That may be so if you’re an American company. But the problem is it is not a one-size-fits-all model,” says Bordiss.

For a country to prosper economically, mercantilism and Keynesianism say that investment needs to be the main focus. The idea is that, if there are investment opportunities, savings and income will take care of themselves.

Countries in southeast Asia like Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam have capital controls stopping capital from getting in. After the economic crisis, Bordiss explains, these countries realised they could not allow the free flow of capital so they stopped capital coming in — but they had lots of productive industry, which meant capital was constantly knocking at the door.

“The problem in South Africa is that we have made these laissez-faire laws which have allowed capital to come in and out with no interruption so our economy is focused on savings, which is fine; the only problem is there is nothing to invest in,” says Bordiss.

He explains that there is nothing to invest in because the top productive sectors, capable of soaking up millions of unemployed South Africans, such as mining, agriculture and manufacturing, have not been looked after and require policy reform to make it easier to run an industrial concern in South Africa.

“Making the laws as easy as possible means things like a continuous power supply because you can’t run an industry without power; you need to get your product to the ports so we need to ensure that we have functioning railways or road networks to get products to the ports … these are practical things that laissez-faire capitalism does not focus on,” Bordiss says.

In the 1970s, the model began to change from one of production to one of consumption when the Nationalists started changing their minds and started to implement laissez-faire market reforms in order to compete in “the new world” which had become the popular thinking in Europe and the West when former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and former American president Ronald Reagan were in power respectively.

Shadow of Liberation by late South African economist Vishnu Padayachee, who happened to be Bordiss’s supervisor, and Robert van Niekerk details how the ANC economic policies in the 1990s came to be formed.

“They basically rolled over to the National Party. The National Party and organs of the state which were still under their control, like the Reserve Bank, the Development Bank, pushed for free movement of capital, the dropping of tariffs, the dropping of industrial policy and the ANC bought into that,” explains Bordiss.

“Indeed, 1994 did not bring liberation for the working class, and the black section in particular,” says Hattingh, adding “Rather it was a deal between a black and white elite and this deal defines how the capitalist and state system operates in South Africa presently.”

Hattingh explains that, as part of this deal, white capitalists were assured that their wealth would not be touched post-1994. “Hence a large part of the private sector is still owned by a white elite (not the white working-class though) even though there has been some narrow black economic empowerment and more foreign ownership of shares of companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange,” says Hattingh.

In Book 5, chapter eight, of Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith writes, “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production. And the interest of the producer ought to be attended to only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.”

“That is an unbelievably terrible idea,” says Bordiss, explaining his reaction with an example concerning chicken imports.

“In essence, this means South Africans can get cheaper chicken from America. Americans give their leftover chicken to South Africa, which completely destroys our chicken industry. We sit with over 32% unemployment but we’ve got cheap chicken.”

Another example to illustrate the dangers of Smith’s idea is the demise of South Africa’s once-booming textile industry, which began to unravel when local manufacturers were unable to match cheap imports from Asia.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the City of Cape Town was the hub of South Africa’s garment and textile industry. As the leading employer of labour, the clothing manufacturing sector in Cape Town alone was a significant contributor to the South African economy.

“In 1996, we reached the high point in clothing, textile, leather and footwear employment in the country, which is about 260,000. Subsequently, the numbers have come down (formal sector only) to about 90,000,” says the national industrial policy officer for the Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers Union (SACTWU), Etienne Vlok.

Hattingh says capitalism in South Africa still has many of the features it had under apartheid, although there have been some changes.

“The key feature of capitalism in South Africa is that the massive profits of corporations in the country have always been and continue to be based on the low wages of the black working class. It is why the black working class (workers and the unemployed) remain impoverished and subjected to racism in South Africa,” he notes.

What needs to be done?

In South Africa with an unemployment rate sitting at over 32%, in terms of industrial policy, Bordiss says we need to focus on the sectors that can soak up the maximum number of unemployed people and make it as easy as possible to operate while promoting black industrialists.

On this point, Bordiss says that we can take a page out of Turkey’s book.

When he first assumed his position as the president of Turkey, Tayyip Erdoğan held a conference with all the top European fashion brands and asked them to make a list of factors that would make Turkey their first choice within which to manufacture textiles and apparel.

Erdoğan gave this list to his minister of trade and industry to implement and, within the space of a few years, Turkey was manufacturing a large amount of Europe’s top fashion apparel and textiles and in 2020 was ranked the world’s fourth-largest textiles exporter.

Bordiss believes South Africa similarly needs to sit down with the miners, the clothing manufacturers, the farmers and discuss what is needed to kickstart each industry.

“The neoliberals say, ‘Just leave it to the markets, it will be the same answer everywhere’. But it is not the same answer everywhere. What the miners need is completely different to what the shoe manufacturers need, which is completely different to what the farmers need and what a wine farmer and a wheat farmer needs is probably different, too. So you need to drill down industrial policy per sector,” says Bordiss.

Should Basic Income Grants be rolled out?

Bordiss explains that the idea of a Basic Income Grant is favoured by the laissez-faire capitalist school of thought because it is a way of putting money into the system but leaving the basic structure of the economy unchanged.

“We have masses of people who are literally starving. So we don’t really have a choice,” says Bordiss, but explains that it is a short-term solution that needs to be handled carefully.

Bordiss explains that in order for a Basic Income Grant to work, money supply will have to be increased. This can lead to the danger of printing more money and severe inflation.

A case in point was Zimbabwe in the late 1990s when former president Robert Mugabe exploded money supply and inflation skyrocketed.

The trick, Bordiss says, is to focus on investment to offset the possibility of inflation. “You increase the money supply but at the same time increase the amount of production in the economy, then prices won’t move by substantial amounts,” he explains.

An example of where this worked very well was in America during the 1930s, when Franklin D Roosevelt was president. Roosevelt engaged in massive deficit spending to increase money supply but he built infrastructure like roads, dams and bridges to increase production so almost no inflation was experienced.

“Basic Income Grant is an immediate solution and fine as an emergency measure, but it is not a long-term solution. If you are going to print money, you need to employ people and grow production so that your price levels won’t go through the roof,” says Bordiss.

We have got to get mines working; farmers productive; manufacturing concerns going again; that is what is going to soak up the unemployed,” Bordiss adds.

The idea he describes comes from the post-Keynesian period and is called a “job guarantee”. It is an alternative to the Basic Income Grant.

“One thing about a job guarantee — the idea that the state must find out where it can employ people to do the jobs that the private sector isn’t doing — is that you’re building skills, changing the structure of the economy and lowering unemployment,” says Bordiss, adding, “There are a whole lot of people who previously felt useless because they had no role to play in the productive economy who are now fixing potholes, for example.”

The circular economy

Three years ago, Vice News covered the story of the Twin Oaks community — referred to in this short film as a “co-operative living situation” — in Louisa County in the US state of Virginia, which was labelled as having “dropped out” of mainstream capitalism.

It is an income-sharing community and generates a sizable income of $600,000 per year in profit from making and distributing tofu and hammocks to big corporate retailers in the city with whom they have formed partnerships.

Everyone who lives in the community specialises their labour to what they are most suited to, whether that’s tending to the food farm or construction. In exchange for the 40-hour work-week, residents get lodging, healthcare, food and a small allowance.

“In the global war of ideas, capitalism has won. The other ideas have lost. What we are wrestling with in our global culture is what “brand” of capitalism is going to win,” says the longest residing member of Twin Oaks, Keenan Dakota, in the Vice film.

“Twin Oaks runs a capitalist business. We sell our stuff in the mainstream market. What we are doing is taking the capitalist system and providing more direct, immediate control,” says Dakota.

It may sound like a “kumbaya” utopia, but the Twin Oaks co-operative living situation is one example of how the future of capitalism might not mean opting out of the system completely, but participating in it in a different way.

Given the tight spot the world currently finds itself in with climate change, efforts to change and improve the the situation, such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Zero Emissions by 2050 goal, speak to an urgent need for countries to adapt and change to a more “circular economy”, possibly through “Doughnut Economics”.

Proposed by Oxford economist Kate Raworth, from the belief that current economic models are “broken and outdated”, Doughnut Economics is an approach that works within the earth’s resource capacity with sustainable options, less waste, support for local industries, and not using past the earth’s resource threshold to “ensure that no-one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend”.

Hattingh points out that a place in the northeast of Syria, known as Rojava, is where the future of capitalism might already be happening.

Rojava is trying to create an egalitarian society without capitalism and a state that is based on structures of direct democracy. It sees women’s liberation as being central to creating a radically democratic and egalitarian society.

“The argument is based on an analysis that sees the oppression of women as being the starting point of the class system. The oppression of women was later expanded by rulers into the oppression and exploitation of poorer men. So they argue, to get rid of class oppression and exploitation, the liberation of women and the ending of patriarchy is key,” explains Hattingh.

Rojava is an outcome of the struggle that has been waged by the Kurds for national liberation. Nonetheless, it has gone beyond even national liberation and has become an experiment to create a confederation of workers and community councils and communes to replace capitalism and the state.

Hattingh explains that Rojava, however, does face threats. The biggest threat is posed by Turkey wanting to stop the revolution from spreading to its territory – which has a large Kurdish population. The invasion is ongoing.

“Despite the threats, Rojava shows a more just society can be created, even in the context of a harsh civil war,” notes Hattingh.

From a mercantilist perspective, where the sole point of production is not just to satisfy the consumer, Bordiss says, “We live in a community and we need people employed and we need to make stuff ourselves because when we make stuff ourselves we build skills in our community, we build a skill base and coercion because you have to set your alarm in the morning and get out of bed, go to a factory and subject yourself to the discipline of working in a group and this is good for society. It increases wealth over time in South Africa and it lowers inequality.”

So, if South Africa can reinvigorate its industrial policies as Bordiss describes, what will this look like in real life?

South Africa is considered a developing economy and one of the most unequal countries in the world, owing to a high unemployment rate and a labour market that is paid very low wages and that is still heavily racialised.

Like other countries, South Africa has historically strived for the hegemonic Western-European ideal of what it means to be “developed”. But Bordiss says it is time to forget the West and look to the East for an idea of what the future could look like.

“The problem I see with South Africa is that we are obsessed with America and their issues, from their social issues to modern monetary theories; yet the Americans have deindustrialised, their wage rates are decreasing, American workers are poorer than they were 40 years ago, and I don’t see America as the great hope for the next century.

“Asia on the other hand has been lifting millions of people out of poverty. It has captured a massive chunk of total production. So, if we are looking forward to what our economic system will look like, I think we need to look to Asia for inspiration because that has been the success model of the last 40 years. Why are we obsessed with a model that is no longer a cutting-edge model?” asks Bordiss.

“We need to look at what the likes of China, Japan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan and Korea have done right and then see how we can adapt that to an African environment,” Bordiss says.

He believes it is essential to a long-term solution to shift thinking away from Basic Income Grants and consumption and onto production and getting more people involved in the economy.

“The state has almost collapsed under Zuma. We had a reasonably well-functioning state under Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki but Jacob Zuma slowly but surely hollowed out the state,” notes Bordiss as he adds that there is no chance of prosperity without a functioning state.

“There is no country in the world that can thrive without a competent state; it is not possible, it does not exist. There is no other option, we must fix the state.”

Coupled with a competent state, Bordiss believes the whole country needs to buy into an upliftment project.

“The project needs to be massive, credible, believable and achievable and, hopefully, if we can get enough people to buy into it, the corruption will be less because I think an element of why corruption happens is because people don’t believe in the project,” he says.

“Africa has not covered itself in glory in the last 50 years but there have been pockets of excellence. And just because we haven’t done so well in the last 50 years doesn’t mean we can’t do well in the next 50 years. We can adapt, we can choose a different way, we can come up with a new vision. It is possible.”

Image: Fikry Anshor / Unsplash

An end to capitalism?

Hattingh says capitalism is a system that evolves and he foresees a grim future for society should it continue on its current trajectory.

“In all likelihood, we will see further increase in social problems in black working-class communities as people feel the pressure. Racial tensions will continue to be a feature of society due to massive inequalities if capitalism remains. Likewise, the state will increasingly be used as a source of private accumulation by politicians,” Hattingh says.

Kate Raworth, whose Ted Talk, Doughnut Economics, received immense praise, says: “Economics is broken. It has failed to predict, let alone prevent, financial crises that have shaken the foundations of our societies. Its outdated theories have permitted a world in which extreme poverty persists while the wealth of the super-rich grows year on year. And its blind spots have led to policies that are degrading the living world on a scale that threatens all of our futures.”

How do we change the so-called “invincible” economic system?

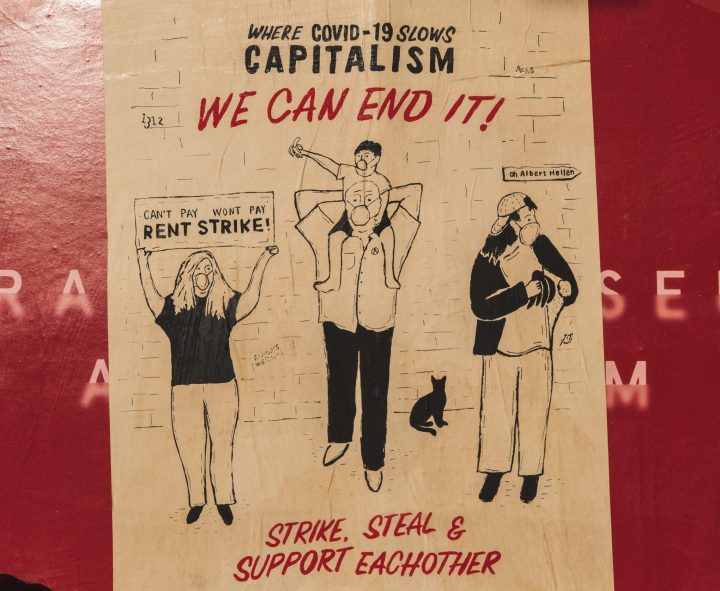

Hattingh says capitalism is unlikely to simply dissolve, especially when the ruling class has an interest in maintaining it. However, there is a chance it could come to an end through counter-culture movements or through ecological destruction.

“The only way capitalism – and the state system that keeps it in place – will probably come to an end, in a good sense, is if a majority of people (who don’t benefit from the system) ends it and creates a new, more equal and democratic system. For that, movements have to be built that have a counter-culture that values all of humanity, mutual aid, solidarity, real democracy and indeed prioritise the best qualities of humans, including love, in the broadest sense,” says Hattingh.

“If people don’t build movements to end capitalism, capitalism will continue, but it will evolve, and the only thing that may stop it, is if it literally destroys the ecology through the continuous and expanding extraction it is based on – making large parts of the world uninhabitable: and that is a hideous prospect.” DM/ML

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8832″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Twin Oaks is an amazing concept. But it only works because the economic system of the USA is laizze faire economics, especially in Virginia. If you started Twin Oaks in South Africa a Bargaining council would be at your door demanding that you sign up and offer explicit benefits and pay a hefty association fee per worker. A Twin Oaks contract would be laughed at at the CCMA. Laizze faire economics gives rise to solutions in response to its own failings. It is self correcting. An example is price controls after hurricanes to stop gouging. But where there are no price controls the towns rebuild more quickly because Billy in North Dakota can drive all the way to Florida with building materials thereby adding to the supply.

Blaming capitalism for corruption, mismanagement and theft is a bit to far I think. Previous communist governments have shown that greed in humans seems universal no matter the system behind it. And before we can start extracting ever more tax from the dwindling middle class (because it’s always the middle class that needs to pay the bill it seems), I think it is fair to ask for some transparency and accountability before implementing the likes of income grants (and NHI, a new pension system, free housing etc etc..) and the increase in taxes or the unfettered printing of money that would be required to finance it.

This article reads a bit like a compendium of undergraduate half-truths. I particularly like the idea that love and solidarity, coupled with real democracy, are (maybe) going to trump the global multilateral trading system. Cute!

I stopped reading at “The fact that capitalism is based on the oppression of this section of society” – that is not a fact, and shows such poor understanding of human nature (and capitalism) that I can’t see any point in reading more. Throwing random words at real world problems does nothing to solve them.

No country in the world is capitalist. Capitalism does not tolerate bailouts for example.

The problem with economic theories is they are theories. Rather than academics, ask entrepreneurs and business founders what needs to change. Their most likely answer is for authority to just get out of the way. Don’t ask the overpaid hired help that run big companies, they will ask for regulations, subsidies and help to cope with labor.

I dislike this “one-size-fits-all” theorising. South Africa is not USA. South Africa is not UK, or Germany, or Russia. This article fails to consider several of the South African specifics. In particular, the major European capitalist nations built their wealth by exploiting their colonies. Most of the excess capital earned in the industrial expansion during “the inter-war period” (a term which in itself shows the Euro-centric slant of the author) ended up building the capital base of England (eg where did the gold in the Bank of England vaults come from) not South Africa. The ex-colonies have ever since been playing catch-up, and mostly losing.

This article deploys the same delusional thinking of socialists, that a centralised person or authority can somehow fully understand the inexorable complexity of free market economies. No system is perfect but the best choice is obviously the least harmful one. Poverty has declined massively around the world, contrary to the assertions above, and it is the most free economies that have performed best. Check the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index.

To characterise the autonomous region of Rojava as capitalist is a profound error. Use of markets does not equate to capitalism and predates capitalism. Their society is based on many of the principles developed by Murray Bookchin – social ecology, which is socialist, feminist, ecological and anti hierarchy.

When we stop lying to ourselves, perhaps we’ll be able to see the real reasons for our current reality. And it’s ugly, but not for the reasons listed in this article.

Capitalism, with all its imperfections, works because it is closely aligned to human nature. What is required is an effective use of the taxes that a growing economy provides to deal with the creation of opportunity and an underpin for those least well positioned to help themselves.

Agree wholeheartedly with Karl and Johan.