MAVERICK LIFE OP-ED

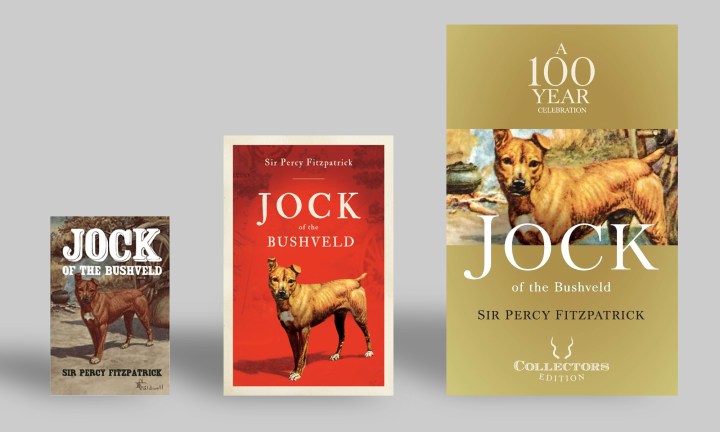

Should we burn ‘Jock of the Bushveld’?

A re-reading of this South African ‘classic’ shows that it is politically and environmentally obnoxious.

Have you read Jock of the Bushveld recently? I have and was, frankly, appalled.

Re-reading the book for the first time since primary school, I was immediately struck by the liberal, almost unthinking, use of racially offensive terms, a huge obstacle for modern readers.

Jock has been published in a sanitised edition, which is what I may have read as a child. Even the 1950s would have found Fitzpatrick’s first edition unconscionably racist and puffed up with the presumption of the white man’s superiority.

The “k” and “n” words are used with horrible abandon. And then there are Percy Fitzpatrick’s bigoted opinions, which he is not shy of venting.

He writes, for example, that leading a wagon over the high berg calls for “patience, understanding, judgement and decision… and here again the white man justifies his claim to lead and rule.”

His world was seen as divided between the “savage” and the “civilised”, the latter being the magical attribute that allowed Europeans to grab other people’s stuff and roll out the Gatling gun if they resisted.

But there is another side to Jock. Fitzpatrick harks back to “the almost unbearable ‘trek fever’; of restless, sleepless, longing for the old life; of ‘home-sickness’ for the veld, the freedom, the roaming, the nights by the fire, and the days in the bush”.

Stock reading for generations of children, the work’s popularity has probably declined in recent years as it recedes into an increasingly alien past. But “home-sickness for the veld” probably explains its residual appeal, more than a century after it was first published.

I closed it thinking about a trip to the Kruger Park, which Fitzpatrick’s wagon train crossed en route to Delagoa Bay in the mid-1880s.

We suburbanites feel the “call of the wild”, as a reconnection with a more authentic condition and source of spiritual renewal – hence the 4×4 brigade and the legion of campers, caravanners, hikers, mountaineers and game park habitués.

Fitzpatrick’s bestseller, and other chroniclers of Africa’s vanishing Eden, like Eugène Marais, William Charles Scully and Karen Blixen, answer to this need.

He is a gifted descriptive writer. And his best writing conjures the solitudes and grandeur of elemental Africa: the “tearing, smashing hail that seemed to strip the mountain to its very bone”; the swollen river “silent and oily like a huge gorged snake”; the “driving glare” and flying brands of a rampaging bush fire.

He also offers insights into the souls of animals, wild and domestic. Fitzpatrick knows his dogs: Jock may be idealised, but he is far more substantial than those faded Hollywood pastiches, Lassie and Rin Tin Tin.

Jock’s black-eyed fury when he fastens onto the lip of the stricken kudu, which then “flogs” him against the ground, is hair-raising in its brutality but undoubtedly grips and fascinates.

The paradox is that Fitzpatrick clearly has a soft spot for “the great passionate fighting savage”, the Zulu Jim Makokel, who is favoured above other drivers and particularly Sam, a literate, Bible-reading Shangaan.

Jim fought at Isandlwana, but now acknowledges “the power of the Great White Queen and the way her people fight”.

This is a familiar trope: during South Africa’s democratic transition, right-wingers like John Aspinall gravitated towards Inkatha as the supposed representative of the noble Zulu warrior and a natural ally against the westernised, nationalist ANC.

But it is Jim and Jock’s unswerving loyalty and tireless service of their master that mainly recommend them to Fitzpatrick – when the oxen are stricken by the tsetse fly and the transport business faces ruin, Jim keeps faith while the feckless Sam disappears.

Jim, Jock and the author are united in their contempt for non-Zulus. This applies especially to Shangaan, who, according to the author’s subsequent Postscript to Jock, are Zulus “degenerated by mixture with inferior races”.

Towards the end of Jock, Fitzpatrick hears, to his evident satisfaction, that Jim has run into Sam and beaten him mercilessly.

Fitzpatrick was an out-and-out British jingo of the Cecil Rhodes variety who later became a wealthy Randlord. Proposing a toast to colonial mandarin Lord Alfred Milner, he said: “I believe in the British Empire. I believe in its glorious mission… I believe in this our native land.”

The word “our” does not include indigenous South Africans, as the Postscript to Jock makes clear: “To west and east every mile has its pioneer – men and women, Dutch and English – Our People who made Our Country [his capitals].”

In his preface Fitzpatrick describes Jock as “a true story from beginning to end”. But it is safer to regard it as a yarn skilfully constructed from scraps of fireside braggadocio on a scaffolding of fact. The late South African critic Stephen Gray argues that the book is a vehicle for the author’s pioneer/imperial values, which he fears are under threat, and that he “garbles” human and canine traits.

His aim is to “reactivate… obedience, self-reliance, adventurousness and common sense which [he] sees as having epitomised the arrival of the European spirit in Africa”.

There is a clear link, also, between empire and game hunting, Jock’s raison d’être and the ground of his relationship with his owner.

Fitzpatrick’s African workers are not permitted firearms; indeed, the University of Zululand’s Michael Brett observes that several 19th-century legislatures viewed indigenous hunting as poaching and blamed it for falling wildlife numbers.

Brett sees a parallel with the deer parks of the English aristocracy, protected from commoners by ferocious anti-poaching laws.

The irony is that trigger-happy Europeans shamefully abused this licence to kill. British historian John McKenzie writes that “few regions of the world had richer… wildlife resources than southern Africa; even fewer witnessed such a dramatic decline in the space of half a century [up to 1900].”

Brett argues that the Lowveld was a “Paradise Lost” by the time of Fitzpatrick’s brief sojourn; many large mammals – elephant, rhino, hippo, giraffe – do not feature in Jock because they were already shot out.

Until Jock’s closing pages – when he remarks on how agreeable it is to watch, rather than shoot a waterbuck – Fitzpatrick shows no awareness of the animal holocaust in the Lowveld and nothing approaching a conservationist outlook.

He constantly thrusts his own value judgements on the processes of nature: with the deer-keeper’s hatred of predators, he abominates hyenas as “high-shouldered slinking brutes” and wild dogs as “cruel beasts” to be shot on principle.

Unsustainable hunting was also a form of asset-stripping and an aspect of wilderness clearance that, early on, underpinned the rapid expansion of colonial rule and settlement. Brett describes it as a “mobile resource” and “the initial survival mechanism of the frontier”.

It also played a part in the development of mining in South Africa – the “Springbok Express” carried thousands of antelope carcasses from Swaziland to feed the gold miners of the Reef.

Fitzpatrick dedicates Jock to “the likkle people” – his four children. But the 1907 edition is very far from being what we now think of as a children’s book.

In many aspects it is, as the anti-imperialist George Orwell called the Union Jack-waving Rudyard Kipling, who advised Fitzpatrick to publish Jock, “morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting”.

What attitude should we adopt to a book that so flagrantly violates post-apartheid norms?

Fitzpatrick had repugnant opinions and a didactic purpose, and some of the crueller incidents could upset children. But suitably abridged, the book can be read as a tale of a man and his dog and their adventures together.

Readers, including young readers, should be allowed to enjoy the exciting incident, the insight into dogs, roosters, horses and oxen, and the evocation of the landscapes and wild creatures of untamed Africa.

The cardinal point, however, is that Jock should also be available in unabridged form. Enormous dangers attach to the idea of “cancelling” historical works that offend against the canons of a later age.

And it has value as a historical document, which describes the mores of the frontier in a turbulent and formative time. The mental habits of the “pioneers” and the language they used are part of this picture.

The depredations of Fitzpatrick and company led to the slow dawning of conservationism and the first steps towards game reserves in the Lowveld, above all the Kruger Park.

For those interested in social history, Jock also offers insights, sometimes unintended, into the human dynamics of the Eastern Transvaal in the 1880s.

It exposes, for example, the elements of slavery that survived in that semi-lawless society. Black drivers were paid – £2 a month, according to Brett – but the habits of ownership were not far away.

This is underlined by the book’s most repulsive incident: the flogging of a driver who has had one too many and persistently disturbs his white master, who is trying to sleep, by demanding meat. After 18 strokes with a sjambok “that will cut a bullock’s hide”, he is untied from the wagon wheel, and can later be heard pleading for water.

Fitzpatrick is shocked rigid: “It made me choke: it was the first I knew of such a thing, and the horror of it was unbearable.”

But he does not intervene, and the reason he gives is significant. He remembers being told by “a good man… straight and strong”: “Sonny, you must not interfere between a man and his boys here; it’s hard sometimes, but we’d not live a day if they didn’t know who was baas.”

You must not interfere between a man and his boys. Stripped of the pious guff about bringing order and light to the Dark Continent, how much that statement says about the realities of imperialism! DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I’ts a reflection of the times and mores prevalent in the past. Learn from the past don’t try to sugar it.

I agree. Why do people want to change history? It happened!

Many things that happened in the past are not acceptable today. That is good, we have developed. However, that does NOT mean that they should be forgotten or erased.

We must learn from history, the good and the bad, not erase it or cleanse it.

There was a time when capturing your colony was a way of life and your power was respected. There was a time when 6 and 7 year olds worked in coal mines. There was a time when you could be expelled from school for being in possession of a condom and remain expelled today…… and it goes on. The world moves on and unless we have the testimony of books, we will never know. The world as we know it has always had evil people with evil thoughts, acti9ns and words. We could ban all those books and bury our heads in the sand or we have a choice to read it with a disclaimer. Just saying.

The Old Testament refers to the common practice of sacrificing the first born child to appease God. Should the Bible be banned for promoting and condoning this violent and anti- social behavior? I think not. History is full of social comment made at the time, through art and music. Why should books or stories be treated any differently?

“The Old Testament refers to the common practice of sacrificing the first born child to appease God.” Huh?? Not my Bible.

Exodus 22

The book was written in the time of Colony – and that’s its context. Acceptable or not, Fitzpatrick did not have the hindsight that we enjoy today.

Have you read The Story of an African Farm by Olive Schreiner? No hindsight there, just a caring human being who put human life before Empire and glory.

But I do agree that context is important. It gives an insight into the attitudes behind imperialism and colonialism, and it paints a wonderful picture of a natural environment that is all but gone.

It’s a tough one Drew, but it is history. An even tougher one is what to do about HC Bosman and his Groot Marico yarns. The reflect the mores of the Boer community, and the use of the K word and accompanying attitudes is pretty much universal. Even though it is a comment on that community, it is a hard sell these days.

Without a doubt, all copies of the book should be burned – but we must go further. Sir Percy Fitzpatrick’s remains and those of Jock should be dis-interred and burned as well.

But there is more. All Staffordshire Bull Terriers should be put down as well and the statue of Jock torn down.

Hey guys, there is lots of work to do on this one!

still laughing!!!

BCMP, you are crazy. Wanna burn your granny as well ?

I’m glad you didn’t make an argument for book burning as we approach banned-book week. I think your argument was balanced and nuanced. For similar reasons, I’d be against destroying all copies of Mein Kampf.

I also happened to re-read Jock recently (almost certainly an unabridged version). The racism and the wanton destruction of wildlife is indeed shocking. However, I support those below (including Drew, above) who argue that original copies of the book must be kept intact. All these books that are uncomfortable to read now are a reminder of where we have come from. Michael Shermer makes the point in his book “The Moral Arc” that one can almost date a book to within a decade according to the language used. These unabridged versions give us a rich insight into the norms of the past; a clear yardstick against which to measure our progress and often a hint as to how further progress might be achieved.

Thank you for bringing this discussion to our attention. Bruce Danckwerts, CHOMA, Zambia

Cannot the “liberals’ not understand that by reading factual history, as sordid as it might be to many people we are able to address the evils which occurred. For example, I do not see the UK burning books about the terrible and racially (not black versus white, but Scandinavians versus the Celts) motivated horrors the Vikings visited on the people living in England, or also what the English did to the Irish, etc. I could quote many other examples where the past is truthfully painted without books being “sanitized”.

Why this predilection in South Africa

As with most of the comments, burning books is not a sensible approach … but analysis and reflections such as that of the author is. Besides … ‘burning’ unnecessarily adds to the challenges of climate change, but does nothing for attitude or values change!

Another comment to add to my earlier one – why do people nowadays get their “knickers into a knot” about literature of the past and views of people calling them various names . The Irish had to put up with 300 or more years of the English calling them various unsavory names, but did not react this way. They just held out and eventually won their country back.

Totally agree with Mally2. Many South Africans are so rediculously sensative, its quite scary!

One of the main reason today that the K word is no longer used in public is that there is fear involved when using it, can get one into a lot of trouble!…….whos foxing who?……. but agreed, why should one intentionally use a word that hurts another in todays world?

History is history and cannot be changed!