The Constitutional Court should not grant the rescission application brought by former president Jacob Zuma, who is imprisoned in Estcourt for 15 months for contempt of court for his refusal to appear before the Commission of Inquiry into State Capture, the Constitutional Court heard on Monday.

Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi for the commission told the court that Zuma was not a “bewildered litigant” who had suffered bad legal advice and who therefore should be granted a rescission of the judgment against him.

As the ConCourt sat for almost 12 hours, KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng burnt, with protests against Zuma’s jailing morphing into near-anarchy and looting in at least 200 malls at the time of writing. Police were investigating six deaths.

Zuma’s advocate, Dali Mpofu, said the former president should be released while the court sat to decide whether to grant rescission of its judgment.

However, Ngcukaitobi said that Zuma’s argument was that even if rescission were granted, he would not return to testify before the commission if it were chaired by acting Chief Justice Raymond Zondo.

“Despite this brazen contempt he persists with, Mr Zuma does not want the punishment.”

Ngcukaitobi said Zuma had been given numerous opportunities to be heard before the court.

“It is one thing to say, ‘I don’t want to participate’; it is another to say, as Mr Zuma has said, that he has reconciled himself to being a prisoner of the Constitutional Court. He knew imprisonment was a possibility, and he reconciled himself with this possibility,” said Ngcukaitobi.

Judge Zukisa Tshiqi asked whether the option of rescission applied, because Zuma had chosen not to be part of the contempt of court proceedings against him.“Is rescission available to a litigant who deliberately decides not to participate?” asked Judge Tshiqi.

Rescission of judgments is only permitted on the grounds of error or ambiguity, and Mpofu argued that the grounds should be expanded to allow Zuma’s application. But Ngcukaitobi was having none of it.

“The threats have not abated; they have escalated. The duty becomes stronger to affirm the dignity and reputation of the court. There is an interest of justice in the finality of litigation,” said Ngcukaitobi.

While rescission is only granted on limited grounds, Mpofu used the application to re-argue many points against the judgment of 29 June that ordered Zuma’s jailing. He said the courts should have referred the case for criminal prosecution of contempt of court with the National Prosecuting Authority, as had been afforded to PW Botha. The apartheid strongman refused to appear before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Judge Mbuyiseli Madlanga said, “at face value, there is no comparison at all” between the two cases as he outlined the differences. To which Mpofu replied: “People out there don’t know those niceties. All they see are two robbers, and one gets off, and one gets 15 months.”

Mpofu said Zuma’s right to a trial and his right to argue in mitigation of sentence had been denied him and that the judgment, therefore, stood to be rescinded.

“It is not a disguised appeal,” he said, adding that the court “relegated itself to be treated as a magistrates’ court” when it agreed to the commission’s application for direct access.

“Once it clothes itself with the robes of a court of the first instance, then it must extend the catalogue of rights in Section 35 [of the Constitution, the fair trial clause],” said Mpofu. To which Ngcukaitobi replied: “That’s an absurdity.”

Judge Chris Jafta asked lengthy and detailed questions on whether Zuma should have been granted a trial and under what circumstances this should have been done. (Jafta had concurred with the minority judgment written by Judge Leona Theron, which found that Zuma was guilty of contempt, but that he should have received a suspended sentence to allow him to appear before the commission and so resolve his contempt of court.)

Jafta asked both advocates whether there was still time for Zuma to appear before the commission, which has been granted a three-month extension to the end of September.

Advocate Michelle le Roux, who appeared for the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution, asked: “Why is the country watching this case so closely?” She said it was because people wanted to know, “Will the court change its mind?”

“What does this mean for the rule of law? What finality means for the rule of law is you accept that you lose. You accept the loss and conduct yourself accordingly,” she argued.

Le Roux said rescission was only granted to fix a patent error or an ambiguity in a court order.

“It’s possible that the false hope of this application may play some role in events rolling across the country. I saw headlines describing it as an ‘appeal’,” she said.

She said that by agreeing to hear the rescission application, the Constitutional Court had caused confusion, with the police and even Zuma himself not sure what this meant in terms of executing his arrest order.

“The chaos and uncertainty are very undermining for the functioning of the legal system,” said Le Roux. “The court is being asked to demolish the law of rescission and to reconsider it,” she concluded. Judge Jafta disagreed, saying that, “Reconsiderations do happen in courts.”

Judgment was reserved. DM

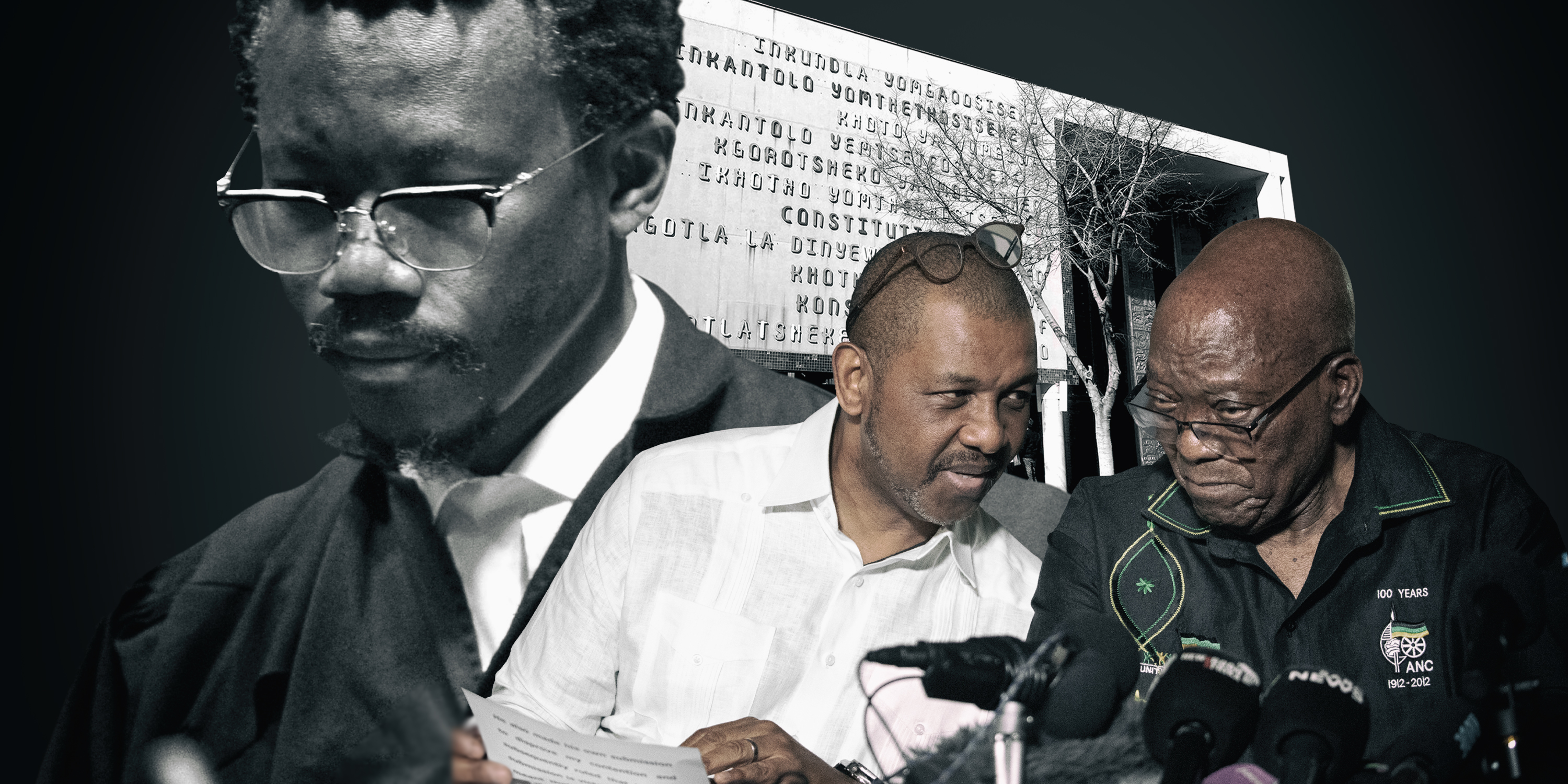

From left: Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi, advocate Dali Mpofu and former president Jacob Zuma. (Photos: Felix Dlangamandla / Leila Dougan) | The Constitutional Court in Johannesburg. (Photo: Flickr / Bharat Vohra)

From left: Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi, advocate Dali Mpofu and former president Jacob Zuma. (Photos: Felix Dlangamandla / Leila Dougan) | The Constitutional Court in Johannesburg. (Photo: Flickr / Bharat Vohra)