BUSINESS MAVERICK 168

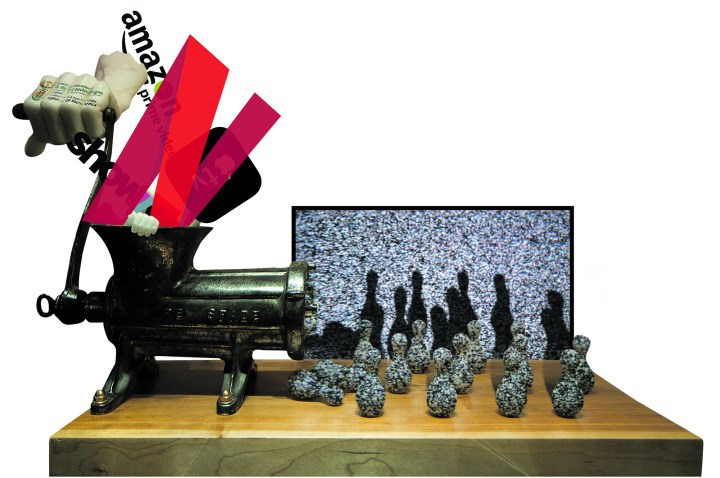

Against the stream: South Africa’s White Paper on streaming services could backfire

The Department of Communications and Digital Technologies plans to enforce local content quotas on streaming services such as Netflix – and make them pay for licensing. Netflix says this places ‘quota above quality’ and will lead to less investment here.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

The government has set its sights on licensing content streaming services and soon it hopes to enforce local content quotas on streaming services.

It’s not quite on a level with Hlaudi Motsoeneng’s 90% local content fiasco at the SABC, but it could well result in streaming services bleeding subscribers as the Communications Department wants on-demand audiovisual content service providers, including those offered over the internet, to pay licences – and stream up to a maximum of 30% local video content.

That could bomb.

Netflix has warned that the White Paper is unworkable and the licensing requirement “not necessarily appropriate”, given the nature of its services and its overall business model.

Public hearings on the Draft White Paper end on 14 June 2021.

The draft document seeks to align South Africa’s policy, legislative and regulatory framework with the Fourth Industrial Revolution, latest communications sector trends, and promote investment in the audio and audiovisual content industries.

It proposes that on-demand content service providers will either apply for an individual or a class licence, based on their annual turnover.

Video sharing platforms, which allow users to upload and share video, won’t need to be licensed, but they are not exempted from regulation on hate speech, protection of minors and related matters, and will need to set up a self-regulated code of conduct or be subject to a statutory code.

The paper also suggests that the Independent Communication Authority of South Africa (Icasa) should remain the regulator of audio and audiovisual content services, but has called for a closer relationship between Icasa and the Film and Publication Board (FPB) to avoid duplication, co-ordinate service regulation and avert regulatory forum shopping.

Netflix launched in South Africa in 2016. Its members choose what they watch, when they watch and how often they watch. Revenues are derived from monthly subscriptions only, with no advertisements. It has invested more than R800-million on South African titles, creating at least 1,800 jobs to date. And, during the pandemic, it spent R8.3-million on Covid-19 relief for TV and film industry workers in SA, endowing 555 beneficiaries with R15,000 each.

Shola Sanni, Netflix’s director of public policy, explained that since its launch the company began working with local creators and distributors to bring high-quality series and films that showcase the best of SA’s creativity and talent to a global audience. “We’ve invested in [more than 60] licensed titles, and commissioned multiple Netflix Original South African series, such as Queen Sono, How To 2 Ruin Christmas: The Wedding, and Blood & Water.

“These two [Queen Sono and Blood & Water] in particular are examples of successful Netflix content produced in South Africa and enjoyed by millions of members all around the world. As at December 2020, there were 70+ South African films and television series available on Netflix, and our members have been delighted by the ability to experience South African storytelling and culture.”

One of the streaming service’s primary concerns has to do with the licensing requirements for audiovisual content services: Netflix believes online content service providers should only be required to notify the regulator and be bound to appropriate regulatory obligations as determined by the FPB, rather than needing to obtain a licence to operate here.

Sanni said further clarity is needed on the licensing. “The fact that linear broadcasters currently require licences does not necessarily mean that online content service providers should similarly require licences.

“The rationale behind requiring telco operators that build out networks, in some instances use high-demand spectrum, and operate equipment to provide services, and linear broadcasting services that have particular public interest responsibilities because of their limited numbers, do not apply to online content providers.”

If online content providers were forced to hold licences and register as distributors and classify content or obtain a self-classification exemption, as well as having to comply with the broadcasting code, the regulatory burden imposed on them will be far greater than what broadcasters have to comply with currently, since they do not have to register with the FPB or classify their content.

“Even in the absence of specific regulatory compulsion at the moment, Netflix is already making significant industry, enterprise and supplier development contributions through content and production investments, skills development and job creation,” Sanni said.

Instead of imposing a local content quota, Netflix believes the focus should be on incentivising content producers to invest in local production. The service also highlighted that comparisons between SA and the EU are “wholly inappropriate”, given that the 30% local content obligation in that jurisdiction is fulfilled by content from across Europe, serving 450 million people, rather than local content of only one member state.

Content quotas also have undesirable effects. Citing research from the London School of Economics, the Netflix presentation notes that “overly onerous content regulation could result in quantity over quality of local content, when fixed production budgets need to be stretched to meet content quotas, and the industry rushes simply to meet these requirements instead of focusing on remaining competitive”.

Without being forced to, Netflix said it has heavily invested in growing SA’s creative industry and is in line with its model, which is predicated on investing in local partners and creatives.

“Netflix [already] invests significantly in local content, and in response to consumer demand, our investments in South African content is projected to grow exponentially in the coming months and years. Given the practical difficulties, the proposals in the draft White Paper could well lead to lessened investment, if retained in their current iteration, which inadvertently elevate quota over quality.” DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Smells to me more like another stream of revenue via licensing and taxing for our corrupt ANC cadres to steal….