TRAVEL IN TIME

Echoes of ancestry: Memories and discoveries around the Cradle of Nature

Standing on a mound of ruddy looking rocks from the ancient rooihoogte formation, with Krugersdorp, and city skylines fringing the hazy afternoon horizon, a geologist pointed out that it was these dolomite rocks that first gave off oxygen, making life on earth possible.

When I entered the balconied restaurant at the Cradle boutique hotel last year, greeted by savanna grassland and thickets rolling out to the Magaliesberg range on the horizon, I realised I’d been here before.

We, my sister, nephew and myself, visiting from Cape Town, had taken our mom there for her 80-something birthday, about ten years ago. It was called Cornute, and while the meal was forgettable, we were there for the view, the sense of place and occasion, as much as the food.

She had always loved those Highveld hills.

Those same hills are now the part-time office of a longtime professional acquaintance and friend. His name is Howard Geach, a geologist who’d been a member of the team that started andBeyond lodges (then Conservation Corporation Africa) about 30 years ago.

He’s now a fellow private tour guide, a colleague in conservation, specialising in showing tourists around the geology, wildlife and hominid discoveries in the Cradle Nature Reserve, in the Cradle of Humankind.

That’s where the bookings he takes, via email at home in suburban Johannesburg some 45 minutes away, assume life. After meeting his guests for a morning drive at the reserve’s boutique hotel, with coffee and croissants consumed, he sets out into the hills in a hotel game-drive vehicle, sharing his story of man’s origins.

By all paleontological and geological accounts, there was relatively significant life here back in early prehistory, providing Howard with ample ingredients for his storytelling tours. These are the hills and valleys where Professor Lee Berger, five years ago the Research Professor in Human Evolution and the Public Understanding of Science at Wits University, conducted his research.

Professor Lee Berger at the reveal of the discovery of a new species of human relative, Homo Naledia at The Cradle of Human Kind on September 10, 2015 at Maropeng in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Beeld / Denzil Maregele)

Wits Vice-Chancellor, Adam Habib, Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa and Professor Lee Berger reveal the discovery of a new species of human relative, Homo Naledia at The Cradle of Human Kind on September 10, 2015 at Maropeng in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / The Times / Alon Skuy)

It was on one very such field trip in 2008, at a site called Malapa, where his father was discussing paleo business with a colleague, that Berger’s nine-year-old son Matthew found a rock containing a fossilized hominid bone. Matthew, being his father’s son, would’ve known that it was a bone, but as Howard explains it to his clients standing above the pit, there was no person more qualified than himself to identify it as a human shoulder girdle.

For not only had Berger studied the bone structure of hominids under the globally acclaimed paleoanthropologist, Professor Phillip Tobias, but his doctoral studies had focused on the shoulder girdle of early hominins. This discovery of Australopithecus sediba was a massively significant find, and while lending colourful narrative to Howard’s tours, it gave the Kansas-born and Georgia-raised naturalised South African professor a critical boost in support of his inevitable academic requests for increased funding to support his research.

The discovery of a new species of human relative, Homo Naledi was unveiled at The Cradle of Human Kind on September 10, 2015 at Maropeng in Johannesburg. (Photo by Gallo Images / Beeld / Denzil Maregele)

The young male Australopithecus sediba (which Berger posited to replace the famous east African ‘Lucy’ as the most likely immediate ancestor of our own genus, Homo) had put the cat among the paleo pigeons and had paleoanthropologists around the world twittering their concerns about teeth and bones. An older girl was found alongside him.

Known as MH1 (‘Malapa Hominid 1’) and MH2, the specimens are on display in the small museum that Berger, in collaboration with Wits University, recently opened at the Cradle boutique hotel.

One of the rooms in the new Malapa museum. Images by Angus Begg.

But Malapa had not finished with the professor’s team of diggers.

Today the collapsed cave is characterised by bits of string draped across a yawning ‘pit’ of rock and earth, underneath an award-winning architectural viewing platform, the construction and erection of which is worth a lunch in itself.

Within the rocks in that pit are fossilised teeth and bones that Prof Berger’s team believe are lying beneath a sabre-toothed cat. While pointing them out to a group of us with his intermittently working laser-pointer, Howard says it’s the second most important hominid site in Africa, after Berger’s other significant dig, the Rising Star cave complex, over a couple of hills and around the proverbial Highveld corner.

The award-winning observation deck over the ongoing Malapa dig – the deck’s story is compelling in itself. Images by Angus Begg.

Images by Angus Begg.

The new tented fly camp, from where walks can be conducted daily. Images by Angus Begg.

Rising Star in 2015 revealed 2,000 fossil fragments, making up 21 male and female homo naledi adults and infants. They are anywhere between 236,000 and 335,000 years old.

What I didn’t initially understand, confounded by all the talk of ‘billions’ and ‘millions’ and rocks and fossils tumbling between the evolution of both humankind and earth, was what the approachable professor had told me in an interview last year: Rising Star was the richest fossil hominid site on the planet.

We were sitting in the same restaurant, on roughly the same table that we’d sat with my mother.

The numbers involved in deep palaeontology discoveries are mind-boggling. My mom wasn’t great with numbers, a bit like my stunned comprehension of standing with both feet on rocks, near the entrance to the hotel, that are separated by 500 million years. In fact, she might well have drifted off, octogenarian style, mid-conversation.

But what caught my breath (and would have jolted her awake), was Berger’s news about these distant ancestors, discovered in caves a few kilometres apart. He told me, repeating a 2017 television interview, that Homo naledi was walking these hills at about the same time as homo sapiens.

Assisted by his significant geological nous, Howard has learnt in his five years guiding tourists around the discoveries of Berger at Malapa and Professor Robert Broom in Gladysvale, that the calcite found in the dolomitic limestone formations makes for perfect preservation of hominid bones.

Not just in the caves and subterranean chambers, but in the sinkholes too. “Deathtraps and bone collectors” he calls them, as we stood around one of many such depressions to be found on those hills, with the Johannesburg skyline far in the distance.

Many Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi, fleeing screaming from a sabre-toothed tiger, maybe like the teenage MH1, will have fallen into such pits, with their remains preserved, buried in the breccia (Italian for ‘concrete’) for future palaeontologists to stumble over while hunting the hills of the Cradle.

Which to my layman’s mind maybe explains why outside the entrance to Gladysvale, where Howard says about 200,000 mostly fauna fossils were found (only six hominid bones among them), so many are to be found in the breccia. Apparently, the miners working the lime kilns around the Anglo-Boer war, before this pre-history was known, were proficient with dynamite, while the palaeontology students working the caves had interest only in hominid bones, and would toss rocks housing anything else over their shoulders.

Which makes Gladysvale quite perfect for young, appropriately curious minds. Like the wing of the barn owl near the cave entrance, in the process of being fossilised, the experience is nothing short of mind-boggling, as one guest described it (although not quite in such courteous term).

Entrance to Gladysvale cave. Images by Angus Begg.

Cradle Nature reserve looking from the hotel flycamp through a V poort to the Magaliesberg – midday, shades of blue. Image: Angus Begg

Illustrations back at Prof Berger’s small museum make the experience more digestible, which is why it is recommended to pass through before diving deep into Howard’s world. They reveal, with the displays and diagrams, how Berger’s team imagined the Cradle landscape would have changed, together with the wildlife, evolving ever so slightly over millennia.

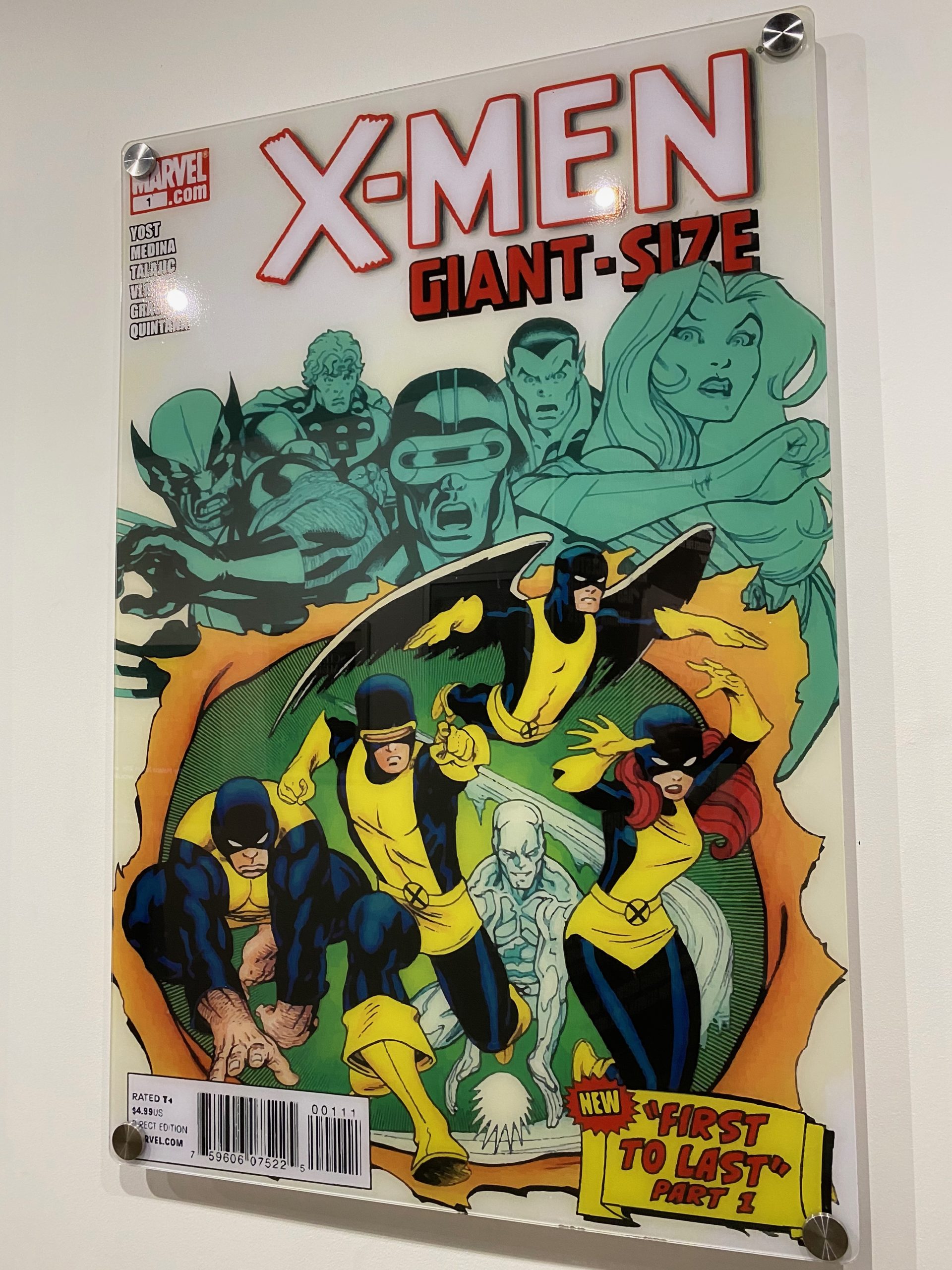

Australopithecus sediba even made it into the Marvel series, courtesy of a chance encounter Berger had on a flight to the US. Image: Supplied

Those hills today are populated by herds of blesbok, eland, red hartebeest and blue wildebeest, with the occasional giraffe down in the valleys and black-breasted snake eagles gliding along near rocky horizons. Jackal are loud and numerous at night, and two meerkat dens have been identified.

Battlefield guide and author Rob Milne says that amongst the battles, wildlife and breccia more battles were fought in these hills than KwaZulu-Natal, where the battlefields of Isandlwana and Spioenkop are found.

Cradle Nature Reserve landscape – walking down from the hotel. Image: Angus Begg

For the nature enthusiast, it is easy to get excited about wildlife so close to Johannesburg, the proverbial big and sprawling smoke. As it is for those who pursue trees and plants, Howard’s excitement at coming across a ninth and tenth colony of a rare and endemic Highveld grassland orchid, we found while hiking en route to lunch on a koppie, was clear.

Yet nothing is separate, these aren’t ‘silos’, I mutter inwardly, using corporate-speak to remind myself of my mantra, that people, creatures, water, insects, soil, plants and the air we breathe are all connected. It helps me digest the Cradle experience; the billion-year-old rocks and plants as a starter, the hominids as main course and wildlife, termites and birds as dessert, with the universe as the table.

Big picture stuff.

Which is pretty much how I felt on my first excursion out into those Highveld hills (a few years after Mom’s birthday lunch) almost a year ago.

Battlefield guide Rob Milne entertaining guests with stories of battles and skirmishes that took place on almost every koppie. Image: Supplied

Blesbok behind the rooihoogte. Image: Supplied

I was standing on a mound of ruddy looking rocks from the ancient rooihoogte formation, with Krugersdorp, suburban Randburg and the Sandton and city skylines fringing the hazy afternoon horizon, when the geologist in Howard explained that it was these dolomite rocks that first gave off oxygen, making life on earth possible.

“You mean these rocks?” I asked, pointing beneath my boots.

Yes, he said. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Perhaps have a scientist read through an article like this before publishing? It wasn’t really the dolomites that produced the oxygen, for instance.

Stromatolites shall set you free. Lovely piece.