Maverick Citizen: Tuesday guest editorial

The farce of public participation in budgetary processes – and how to fix it

Those who are reliant on adequate social housing, public schools and healthcare, and who are the most affected by fiscal austerity, are again being subjected to ‘historical silencing’. Budget by budget, we are witnessing decisions that take us further from the goal of social justice. A plan to democratise the budget-making process is desperately needed.

Kavisha Pillay (Head of Campaigns at Corruption Watch), Daniel McLaren (Budget Analyst at SECTION27) and Sam Waterhouse (Project Head of the Women and Democracy Initiative at the Dullah Omar Institute) are steering committee members of the Budget Justice Coalition.

Recently, a distressing report appeared in The Sunday Times: 32-year-old Russel Makhubela allegedly poisoned his two-year old daughter and then tried to kill himself, because he believed that they should “die together as a family rather than suffer through poverty”. In his desperation, Russel asked his wife: “What’s the use of collecting firewood? We will have nothing to eat tomorrow.”

Access to sufficient food and relief from economic hardships are fundamental rights entrenched in the Constitution, but enjoyment of these rights remains elusive for millions of people who continue to be marginalised both by the economy and by the government’s economic measures. This outcome – of gross economic inequality and minimal redistribution by the state – goes hand in hand with marginalised people’s exclusion from governance processes, including the budget process.

The constitutional commitments to democracy, social justice and human rights locate the democratically elected legislatures at the centre of ensuring a “government by the people”. In South Africa, national, provincial and local government elections provide for broad political representation, but once elected the legislatures and councils must ensure ongoing meaningful public involvement with lawmaking and oversight processes.

Fifteen years ago, the Constitutional Court, in the Doctors for Life judgment, made it clear that public involvement in parliamentary processes is an essential requirement in South Africa’s democracy. This historic judgment confirmed that the public’s power extends beyond the ballot box, and that elected representatives have a responsibility to ensure that legislatures are inclusive of those who “have been victims of processes of historical silencing”.

The judgment stressed that this must include people “who are relatively disempowered in a country like ours where great disparities of wealth and influence exist”. The court stated emphatically that public participation “is not just a matter of legislative etiquette or good governmental manners. It is one of constitutional obligation.”

Despite this landmark judgment, Parliament often fails in its duty to meaningfully engage with the public – treating participation merely as one element in a box-ticking exercise. For those who have tried to engage with the budget processes over the years, this is especially true.

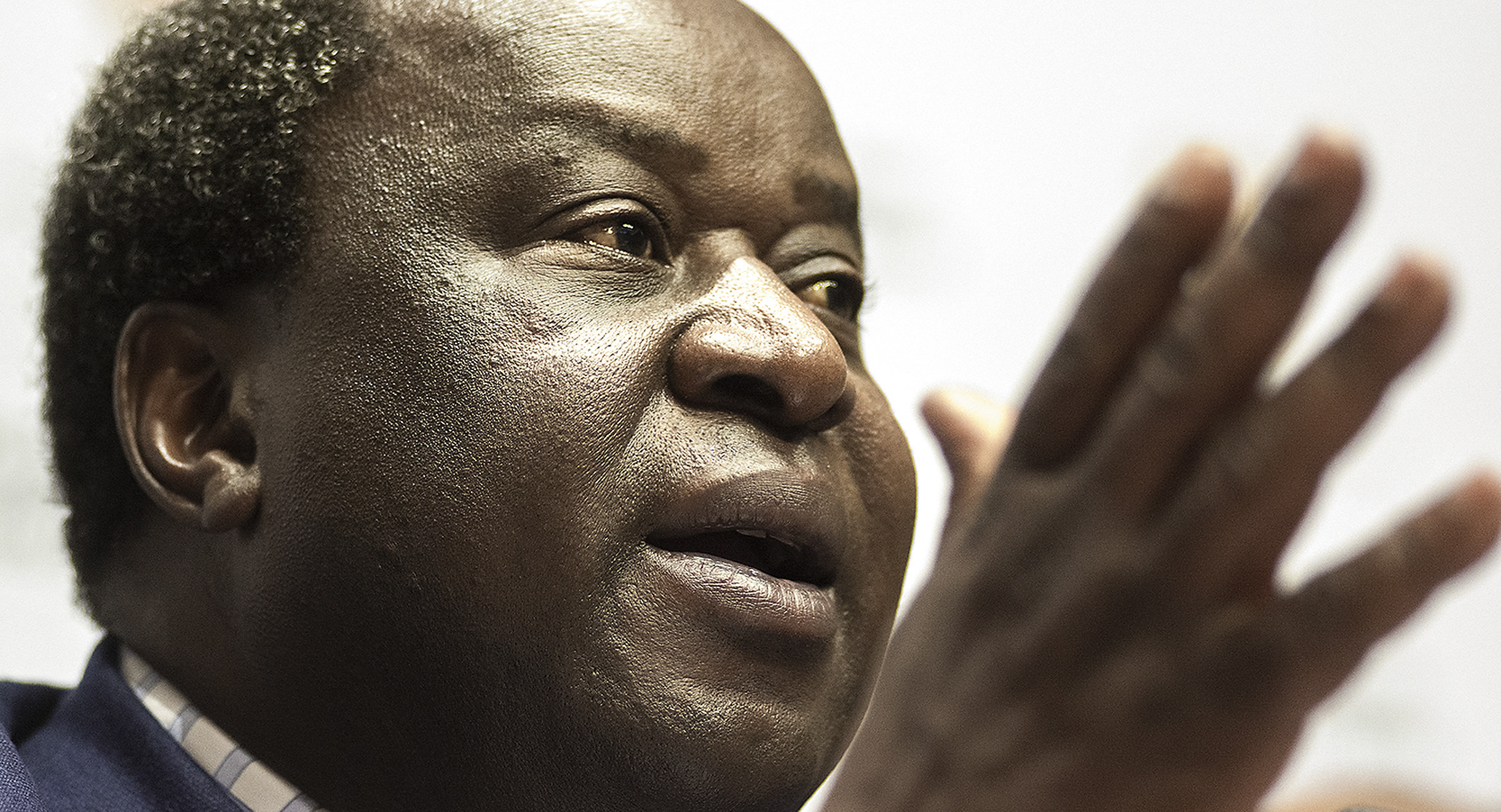

This week, the Standing Committee on Appropriations, in the National Assembly, will conduct public hearings on the 2021 Appropriation Bill. Tabled by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni on 24 February, the bill authorises the expenditure of public funds through different government departments (called votes).

The bill is the third piece of the National Budget that Parliament must consider. The first piece is the fiscal framework, which outlines the overall levels of spending, taxation and borrowing. The second is the Division of Revenue Bill, which divides the budget between the three spheres of government, and provides conditional grants to provinces and municipalities for identified national priorities.

Progressive economists, constitutional experts and social justice movements have rejected and/or sharply criticised the 2021 Budget for deepening poverty and inequality by making broad cuts to funding for socioeconomic rights, including the value of social grants, while reducing income taxes for the wealthy. These criticisms have been repeatedly made and substantiated by these groups in recent years.

The Budget Justice Coalition, a coalition of 20 civic organisations, argued that the 2021 Budget is “indefensible in light of extreme levels of poverty” and called on Parliament to reject it in favour of one that supports employment, livelihoods, gender equality and access to services. But in spite of widespread public criticism, protests and concerns raised with the Select and Standing Committees on Finance during public hearings after the Budget speech, Parliament proceeded with the adoption of the fiscal framework without amendment.

And so, the loop continues – those who are reliant on adequate social housing, public schools and healthcare, and who are the most affected by fiscal austerity, find themselves again subjected to “historical silencing”.

Budget by budget, we are witnessing decisions that take us further from the goal of social justice.

The budget process may be unconstitutional

In the February Budget speech, the finance minister tables the executive’s budget proposals (contained in about 1,000 pages of documents), which is followed by a vote in Parliament, less than two weeks later, on the fiscal framework.

The public only has three working days to table their comments on the fiscal framework and a further two days to prepare a presentation to the finance committees, if they wish to do so. The committees must then analyse all inputs and issue a report either recommending the adoption, amendment or rejection of the Budget, a week after public hearings conclude. To date, Parliament has not rejected or made amendments to the fiscal framework.

This week, the Standing Committee on Appropriations, in the National Assembly, will conduct public hearings on the 2021 Appropriation Bill, tabled by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni. (Photo: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Following public hearings conducted by the Appropriations Committee in mid-March on the Division of Revenue Bill, the committee finally meets to consider the Appropriation Bill – which must be passed within four months of the start of the financial year. These time frames allow the public a longer period to consider the spending proposals.

However, by this stage government departments are already two months into the financial year and have begun implementing, and spending on, their plans. Thus, commenting on the Appropriation Bill during this week’s public hearing is inherently flawed given that the fiscal framework is already in force and any proposal to increase the budget of one programme would require an equivalent decrease to another programme – after all, departments have already started spending.

Thus, there is zero chance of any comment or proposal made by the public influencing the overall outcome in this financial year.

Budget timeframes

Budget decisions are dominated by the executive. The expenditure ceiling for a financial year, which forms the backbone of the fiscal framework, is decided on by the middle of the previous year, when Treasury issues the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) guidelines to departments.

The 2020 July MTEF guidelines indicated that departments’ budgets would be cut by R90-billion in 2021, that there would be “no holy cows” and that “no spending items will be automatically protected from possible downward adjustments”. No public consultations are conducted by Treasury before issuing these guidelines.

In October each year, along with presenting adjusted budgets to reallocate funds due to underspending or changed circumstances, the finance minister makes a Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) providing information on budget policy direction for the next three years.

Here, the public has the opportunity to input both into the in-year adjustments but also in principle into the proposed broader policy direction. However, there is no evidence that public submissions to the MTBPS have had an impact on either the in-year adjustments or the future budget proposals. Like the February Budget, Parliament has never rejected or requested amendments to the adjustments budget or policy direction indicated by the MTBPS.

Despite the constitutional requirements of the national and provincial legislatures to “facilitate public involvement”, as it stands, the public have limited to no influence on budgetary processes, and democratic decision making linked to public finance appears non-existent. Budget proposals that are prepared in the extremely opaque environment of National Treasury, which undertakes little to no public consultation on its overall spending, tax and borrowing plans, have consistently been approved by Parliament, despite public comments and concerns.

This renders the avenues for public engagement, established by various parliamentary committees, pointless and the overall democratic arrangement for the public to influence the National Budget a farce.

When coupled with the profound human rights abuses that result from budget cuts (which in recent years has included cutting funding to schools, public hospitals, social grants, housing programmes, as well as police investigative and prosecutorial budgets which are essential for tackling gender-based violence), we believe the public participation process for the budget fails to meet the standard envisioned in the Constitution.

Democratising the budget process

Given that economic and fiscal policies underpin the realisation of human rights, they require robust public participation. This entails more meaningful engagement during parliamentary processes, as well as creating effective spaces for engagement between the public and the executive, before proposals are tabled in Parliament. At both stages, strong measures must be taken to expand beyond the currently limited and relatively privileged stakeholder groups.

Of concern is that the public, specifically the poor and working class, are excluded from budgetary processes, and thus member-based organisations, civil society and trade unions should be seen as key stakeholders, for both Parliament and Treasury, to conduct budget literacy with communities. The onus remains on Parliament and the government to dismantle the barriers within the current system, which prevents a diverse range of voices emerging.

Lastly, Parliament needs to pass laws that ensure that the development of fiscal policy and budget formulation commences with a process of public engagement. This entails reviewing laws that govern the budget process, from the Public Finance Management Act to the Money Bills Amendment Procedures. These acts do not require any interaction between Treasury and the public and a potential amendment would result in information exchanges between stakeholders and Treasury at key points of the budget formulation stage. Treasury must be required to provide accessible information timously to the public and initiatives such as pre-budget “lockups” must be made accessible and extended to more communities across the country.

Until there is a political will to hear the voices of the public in formulating budget proposals, as well as sufficient timeframes, accessible information and the removal of technical budget language, public participation in the budget process will remain a farce. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.