MAVERICK CITIZEN OP-ED

Being queer or trans can still mean death, even after 285 years of struggle for justice in Cape Town

In each of the stories told below, queer and trans persons have resisted oppression and responded to the pervasive homophobia and transphobia they experience. It is important to honour this history of queer struggle for justice, but while this history marks our progress, how much has really changed in 285 years?

Gabriel Hoosain Khan is the stream leader for inclusivity capacity building at the Office for Inclusivity and Change at the University of Cape Town.

On 3 May 2021, Phelokazi Mqathana (24) was stabbed to death in Khayelitsha for rebuffing the advances of a man. A queer womxn’s life was cut short by a deeply heteronormative and patriarchal world. Since the start of 2021, seven other queer and trans persons have been murdered, a testament to the pervasive homophobic and transphobic violence present in South Africa.

It is in this painful context that an arc of queer resistance unfurls across the city, as long and smooth as the curved sand of Bloubergstrand. An arc linking Robben Island to Camps Bay and stretching from 285 years ago to today.

Remembering this arc of resistance in the week of the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (Idahot, 16 May) can offer us fresh perspectives on the struggles of the LGBTI community in Cape Town and South Africa.

Our arc begins in Cape Town, or rather //Hui!Gaeb, a city in tension where apartheid relics, colonial monuments and indigenous histories shuffle uncomfortably in the city’s narrow streets. Through excavating these tensions, we can understand how the city makes sense of itself, its history and identity.

Take the beautiful Company’s Garden: if we scratch away the winding paths of the English pleasure garden and the stern lines of the Dutch Calvinist vegetable patch, and reimagine the natural slopes before the earth was flattened, we’d find Kamissa – the place that provided sweet water for all.

Remembering one of the city’s original names, Kamissa is an act of resistance in a city where indigenous histories are eroded, and where spatial inequalities play out in the division between the excessive luxury of the Atlantic Seaboard and the awful poverty of the city’s endless informal settlements. It is here, in Kamissa, that the following stories of queer resistance played out.

1735: The trial of Claas Blank and Rijkhaart Jacobs

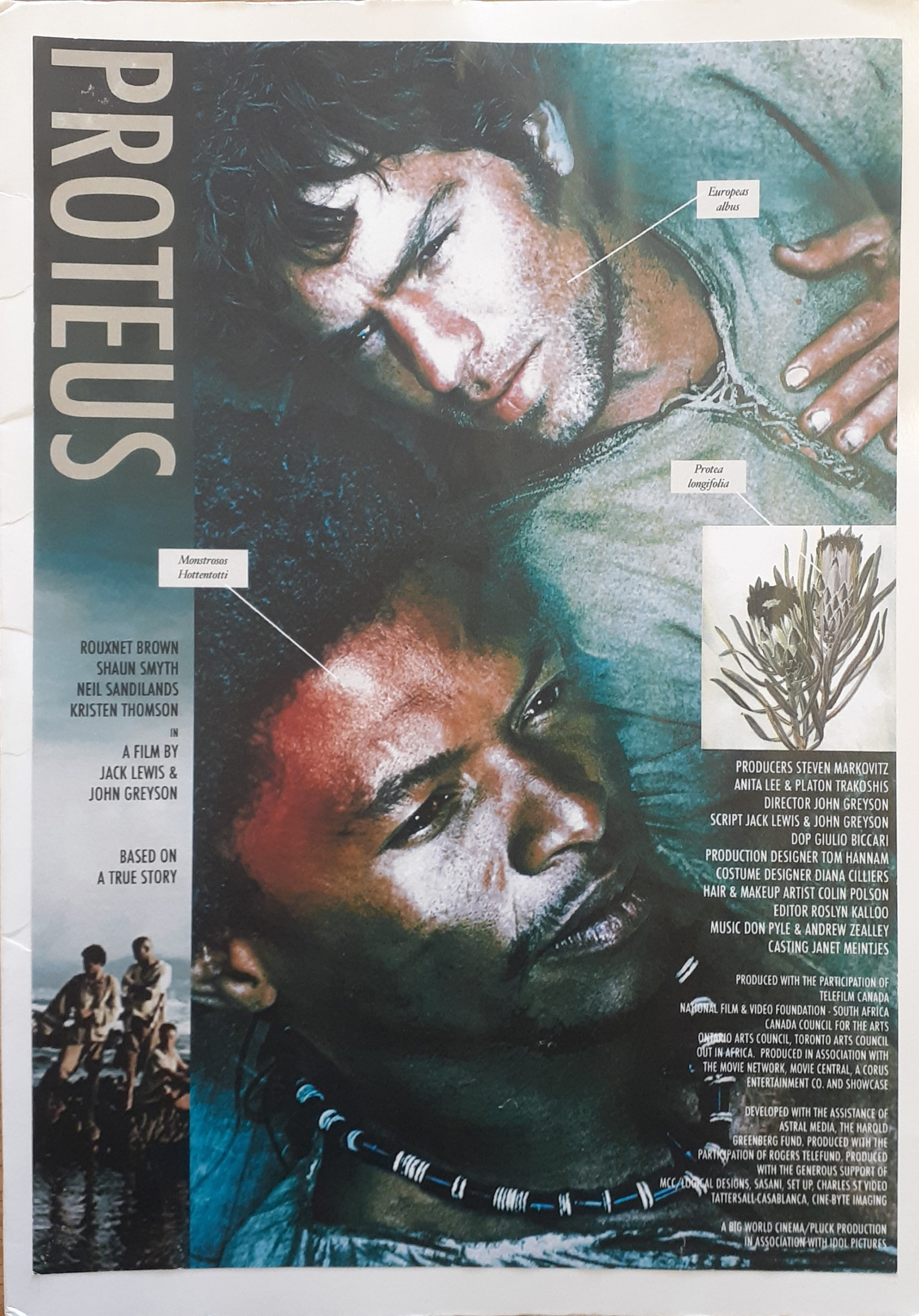

Poster for Proteus, a film about the love story of Claas Blank and Rijkhaart Jacobs. (Photo: Gala Queer Archive)

Around 285 years ago on Robben Island, two men fall in love. Claas Blank, a Khoe cattle herder, and Rijkhaart Jacobs, a Dutch sailor, were imprisoned on the island. Available documentation suggests they met there, built a relationship and shared a “home” together over many years. When the prison warden eventually caught wind of their relationship, they were charged with sodomy, put on trial, found guilty and sentenced to death – perhaps the first example of a same-sex couple being executed in South Africa.

This love story is a poignant reminder of the queer relationships (and relationships across racial divides) in our shared past. These relationships were so threatening to the homophobic, colonial and racist authorities that capital punishment was used as a “remedy”.

While laws criminalising same-sex sexuality and gender diversity ended with or soon after apartheid, the new South African Constitution has not been effective in eradicating the prevalent economic, racial and gender disparities we currently face. Laws and constitutional frameworks are useful, but on their own they do not fill an empty stomach or save us from homophobic and transphobic violence in our homes.

This story is one of an unexpected love, but it is also one of the real and documented colonial violence in the city. Looking out onto Robben Island, I can imagine the short-lived love Claas and Rijkaarts shared; I can also feel and see remnants of that colonial system in the way the city continues to criminalise sex workers, migrants and homeless people.

1815: The jaunts of Dr James Barry

Dr James Barry arrived in Cape Town around 1815, having recently graduated as a doctor and enlisted to be an assistant surgeon in the British Army. He has been described as smooth-faced and having a distinctive high-pitched voice. His boyish looks made the medical school he registered for question whether he was old enough to sit for the examinations, but James never let up and so the medical school eventually conceded.

In South Africa, James was known for being argumentative and sensitive, spending his time hunting, flirting with the prettiest women and challenging fellow officers who crossed him to duel. James also performed the first caesarean operation in South Africa. As the medical inspector for the Cape Colony, he lobbied for better food and treatment in leper institutions and prisons in the city.

Upon James’ death, the woman who prepared his body for burial found something unexpected. James had female anatomy. In an age which limited the roles, opportunities and work a woman could do, James broke boundaries and lived a life we can only assume was authentic for him. I haven’t used the word trans to describe James because it was a word not commonly used at that time and I am unsure if James would identify that way.

That being said, this story is a remarkable reminder of the hidden histories of trans and gender non-conforming people. As a colonial officer and an active participant in British colonialism, James has the privilege of a written history in the form of documentation in archives about their life. I can only imagine the many unwritten histories of gender nonconforming and trans people enslaved at or exiled to the Cape Colony, whose stories are hidden beneath the city streets.

This story is one of a man who lived an adventurous life on their own terms, but is also a story of the continued resistance of trans and gender non-conforming persons who dare to live authentic lives and challenge patriarchal norms.

It is also a story that highlights which stories get old (those of people who already have some power) and which are hidden and erased (those of enslaved and oppressed people).

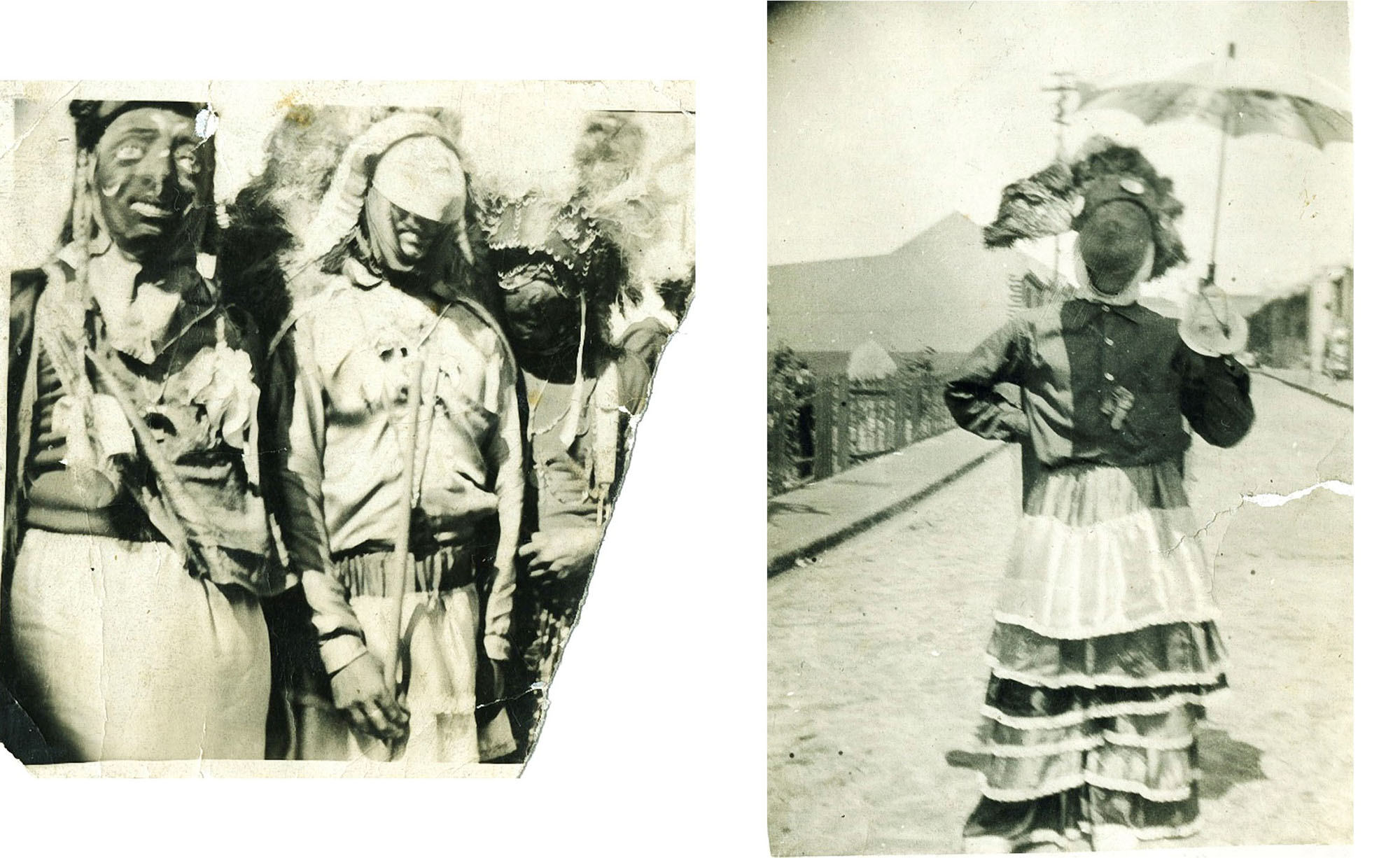

Sometime in the 1930s: A person in a dress in the street

Ninety years ago on a street in District 6 stands a person in a dress staring boldly at the camera. The photo is in black and white but the ruffles of the dress, the umbrella, headpiece and mask all tell a story of vibrant colour. We don’t know much about the person in the image; it’s unclear how they might name their gender: are they attending or performing in a carnival? Is the dress part of the performance? Is it an expression of their identity or a fleeting rebellion?

Regardless of how we might interpret this story, this is one of the earliest photographs of a gender non-conforming person of colour in South Africa. More so, this is an image of a person taking up space, standing in the middle of the road at a time and in a place where queer life was criminalised and pathologised. This image and the rich documentation that followed in later years highlights a vibrant queer culture in District Six.

In 1939, another image from the District Six Museum is labelled, “Moffie troops with a trophy” – in the 1950s, Drum magazine ran a series of articles on the Cape moffie drag culture and the Gala Queer Archive holds a beautiful photo collection of Kewpie, the queen of District Six.

The image and the expansive story hidden underneath it is a wonderful reminder of the rich queer histories and of the connection between queer lives and the apartheid era forced removals in District Six.

In thinking about land dispossession and land return, we need to understand the gender and sexuality dimensions. Efforts to push people of colour to the margins of the city are connected to the way LGBTI people experience violence in exclusionary cities like Cape Town.

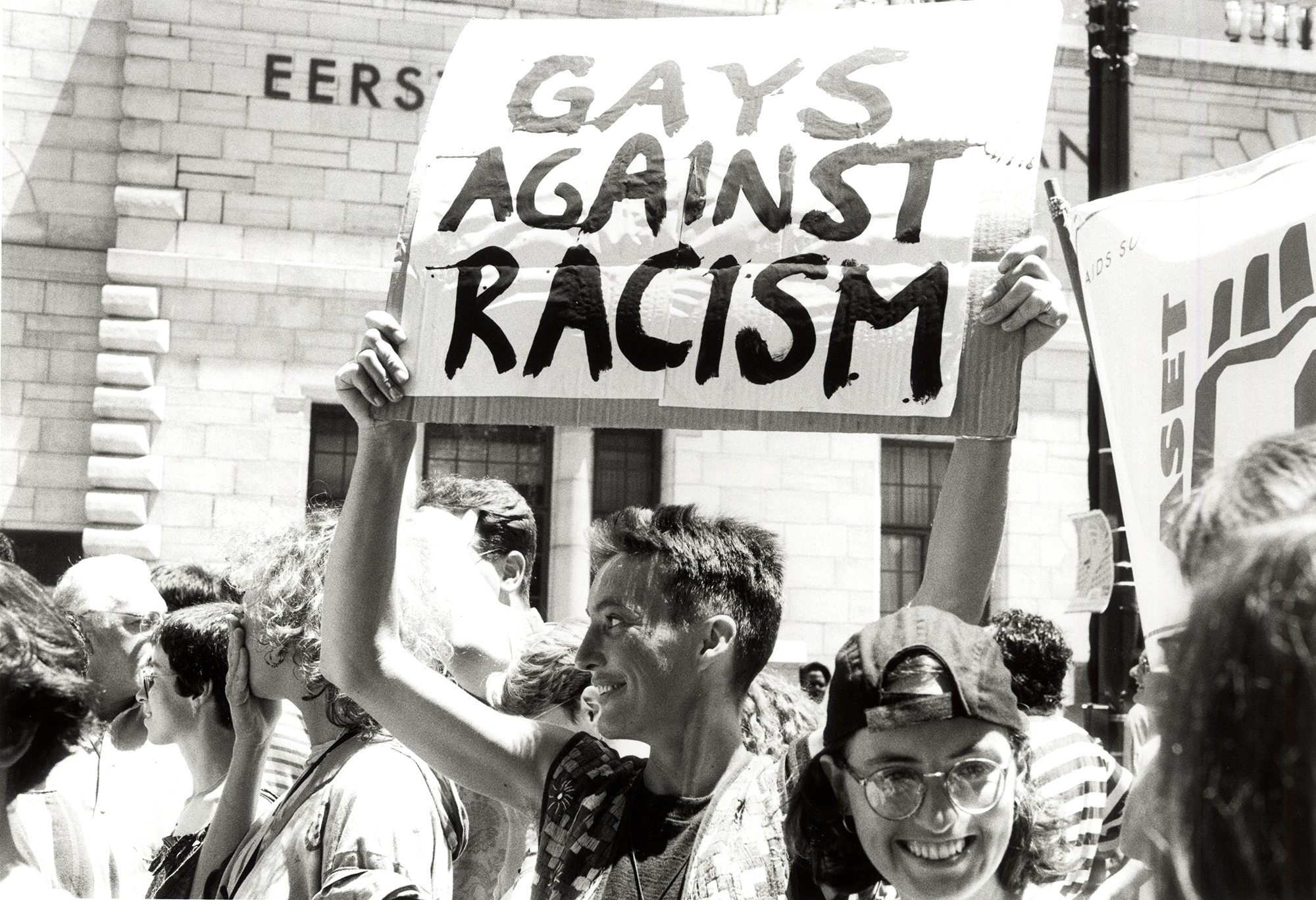

1993: The first Pride march in Cape Town

“Forward to a queer South Africa” reads the tagline of the poster marking the first Pride march in Cape Town. The march was organised by the Association of Bisexuals, Gays and Lesbians (Abigale), an organisation founded in 1992 to provide support to LGB persons who, at the time, had no access to facilities and supportive environments.

Abigale was unique because it predominantly aimed at and organised black working-class people, and it tried to reach people in Cape Town’s townships and outlying suburbs. The organisation also supported queer women at a time when the predominantly male gay organisations were exclusionary.

With almost no resources, a group of activists, including Midi and Zackie Achmat, Theresa Raisenberg, Bassie Nelson and Jack Lewis came together to plan a march attracting hundreds of people. With Albie Sachs giving the keynote address and posters with messages such as “Gays against racism”, “Homophobia = Fascism” and “Queers bash Back”, the march made a strong statement in connecting to South Africa’s transition struggles.

Theresa Raisenberg said of the moment, “I fought for the new South Africa, now I’m fighting for gay and lesbian rights.”

The power of this moment is in the way activists articulated their intersecting struggles as black people, as women and as queers. The city was a point of intersecting oppressions, and their resistance occurred on multiple levels in response to racism, gender inequalities and queerphobic violence.

In this moment, anti-apartheid activists used the wave of changes that came with democratising South Africa to propel queer rights forward for those who were historically excluded.

2020: The We See You occupation in Camps Bay

Flash-forward to 2020: A group of queer activists occupy a mansion in Camps Bay, arguably the heart of white privilege in Cape Town. The group took up residence in a luxurious property available for short-term rental on Airbnb. The collective described themselves as a “Feminist collective of Radical Queer African Artivists, taking residence in a mansion in Camps Bay that wasn’t meant for us. This is one of the most expensive suburbs on the continent. We will put it to better use by creating a home and a space of safety as a ‘chosen family’ of queer feminist artivists.

“Together we will share media, engage in conversations and coordinate resources that will invite people across class, gender identities and sexual orientations into peaceful and transgressive collective actions.”

On social media, some came out to critique the We See You occupation. These criticisms were similar to the colonial and apartheid oppressors from the past – criticisms which foreground private property protections at the expense of dealing with homelessness, queer and transphobia, or the everyday struggles for safety faced by folks of colour in the city.

The occupation, as activism and art, offered a profound critique of Cape Town’s exclusionary nature. The occupation marked the end point of an arc of resistance, with the descendants of the first nations of Kamissa occupying space on land stolen from their ancestors.

In each of these stories, queer and trans persons have resisted oppression and responded to the pervasive homophobia and transphobia they experience. In this week of Idahot, it is important to honour this history of queer struggle for justice in response to a colonial, patriarchal and heteronormative world.

While this history marks our progress, how much has really changed in 285 years?

While being queer doesn’t spell capital punishment by the state, in our homes and communities being queer or trans can still mean death. Let us gather strength from this arc to guide our continued struggle.

Forward to a queer South Africa! DM

Acknowledgements: the District Six Museum and the Gala Queer Archive kindly provided access to the images published along with this article.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

The James Barry story was an eye opener. Thanks for sharing

It is one thing to raise awareness to the plight of the queer. It is quite another to brand all people that believe an occupation is wrong as “colonial and apartheid oppressors”. But hey, easier to just accuse a whole bunch of people, shut them up, than to have an open conversation and a discussion.