DM168 INVESTIGATION

South Africa’s rivers of sewage: More than half of SA’s treatment works are failing

Billions of litres of poorly treated or untreated sewage, industrial and pharmaceutical wastewater are spewed into our rivers and oceans. By the government’s own admission, 56% of the country’s 1,150 treatment plants are ‘in poor or in critical condition’. But this investigation reveals further that 75% of 910 municipality-run wastewater treatment works achieved less than 50% compliance to minimum effluent standards last year.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

Christina Malgas has to daily sweep away sewage and debris that runs along the kerb outside her front door in the township of Dunoon, Cape Town. (Photo: Peter Luhanga)

Air freshener is the only defence 67-year-old Christina Malgas has against the constant stench inside her house. The smell is caused by raw sewage that spills from a manhole cover up the road, then flows past her home in Dunoon, a Cape Town township.

Sometimes municipal workers or contractors come to clear the sewage pipes of blockages. But within days, the raw waste is always flowing again.

“It stinks. We… eventually become accustomed to the smell of faeces. The stench permeates all the rooms in the house. There is no escape.”

Malgas shares her home with eight foster children; the youngest is just one and the eldest 13. The children constantly develop rashes on their skin. She believes this is because of the filthy conditions outside their home.

Malgas’ story is, sadly, far from unique.

Millions of people across South Africa face the health, economic and recreational effects of wastewater pollution caused by a nationwide sewage treatment and disposal crisis.

Daily, billions of litres of sewage spill across streets and gutters.

But this is only one aspect of the massive health and environmental issues the country faces: more than half of the country’s wastewater plants that are meant to treat sewage before releasing it back into the environment are failing. A worrying number are “in a state of decay”.

It’s almost impossible to obtain a full picture of sewer network failures in South Africa’s cities and the towns – this would require approaching 234 municipalities individually for information. Not all record the number of reported sewage spillages; Cape Town is a rare exception.

National data on the functioning of wastewater treatment works and their adherence to sewage treatment standards, however, do exist. Municipalities are responsible for operating wastewater treatment works and must submit monthly reports to the national Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) on the quality of the effluent they release into rivers and, in coastal towns, sometimes directly into the ocean. This is reflected on the department’s Integrated Regulatory Information System (Iris) dashboard.

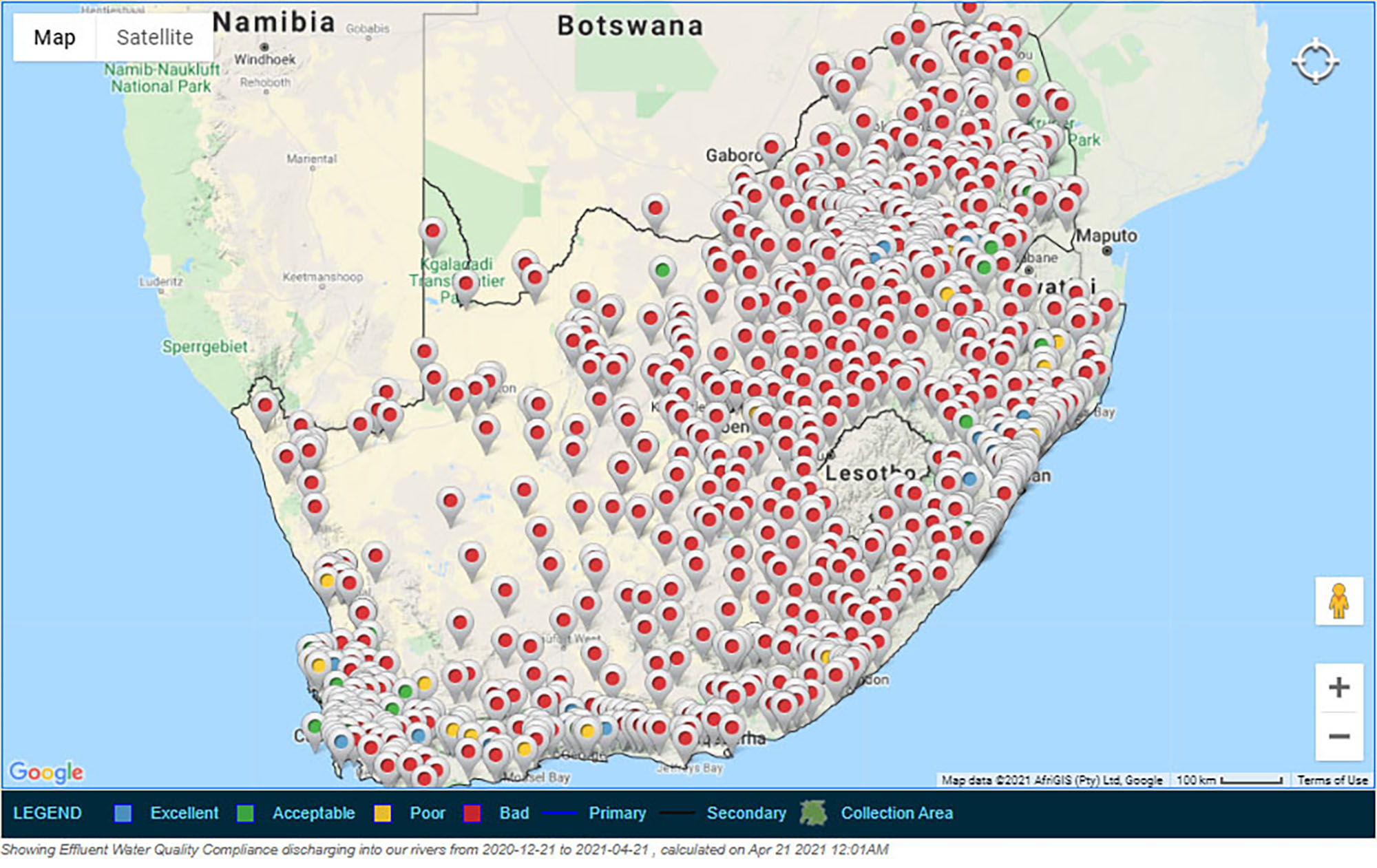

A screenshot of the national Department of Water and Sanitation map showing compliance of waste water treatment works across South Africa. The red markers indicate treatment plants where compliance to minimum wastewater treatment standards is ‘bad’. (Source: http://ws.dwa.gov.za)

An analysis of data scraped from this dashboard is damning: more than half of all South Africa’s sewage treatment works are failing. Each day they spew billions of litres of poorly treated or entirely untreated sewage, industrial and pharmaceutical wastewater into rivers and oceans. By the national DWS’s own admission, 56% of the country’s 1,150 treatment plants are “in poor or in critical condition”. Of these, 265 are “in a state of decay”, says department spokesperson Sputnik Ratau.

But the department’s admission does not reveal the full extent of the rot. The Iris dashboard data reveals that 691, or 75% of 910 municipality-run wastewater treatment works in South Africa achieved less than 50% compliance to minimum effluent standards in 2020.

Even the smallest local municipalities have more than one wastewater treatment works under their jurisdiction. Bitou, in the Western Cape, is the only one of the country’s 144 municipalities responsible for operating wastewater treatment works which met acceptable standards for effluent quality in 2020.

This failure, and the resultant contamination of river catchments, has been ongoing for years, even decades. But Ratau says only two municipalities have faced court interdicts brought by the DWS; a third municipality faces court action.

The data make it plain: South Africa is up s**t’s creek with a broken paddle.

Effluent from the wastewater treatment works in East London is used as a swimming pool on hot days for nearby settlement youngsters whose municipal pool is derelict. (Photo: Nombulelo Damba)

Municipal councillor Hyrin Ruiters at the sewage collection dam in the small town of Zoar, situated in the arid Little Karoo region of South Africa’s Western Cape. Equipment failures have resulted in the raw sewage overflowing directly into a nearby river. (Photo: Steve Kretzmann)

An unused series of sludge dams for purifying sewage in the town of Zoar, situated in the arid Little Karoo region of South Africa’s Western Cape, results in up to 800,000 litres of raw sewage overflow into the Nels River daily. (Photo: Steve Kretzmann)

Reliant on water from a polluted river

“Clearly, there’s something wrong with this water,” says Nobantu Samka. She is talking about the river that runs through the town of Butterworth in the Eastern Cape.

Samka and her wheelchair-bound 18-year-old daughter live in a prefabricated house in a temporary relocation area. They are one of 300 households the municipality moved between the river and an industrial area 12 years ago to make way for a mall which still has not materialised.

She is unemployed, apart from what little income she makes as a sangoma (traditional healer) and receives from her daughter’s disability grant of about R1,800 per month. Like many of her neighbours, Samka keeps chickens and pigs.

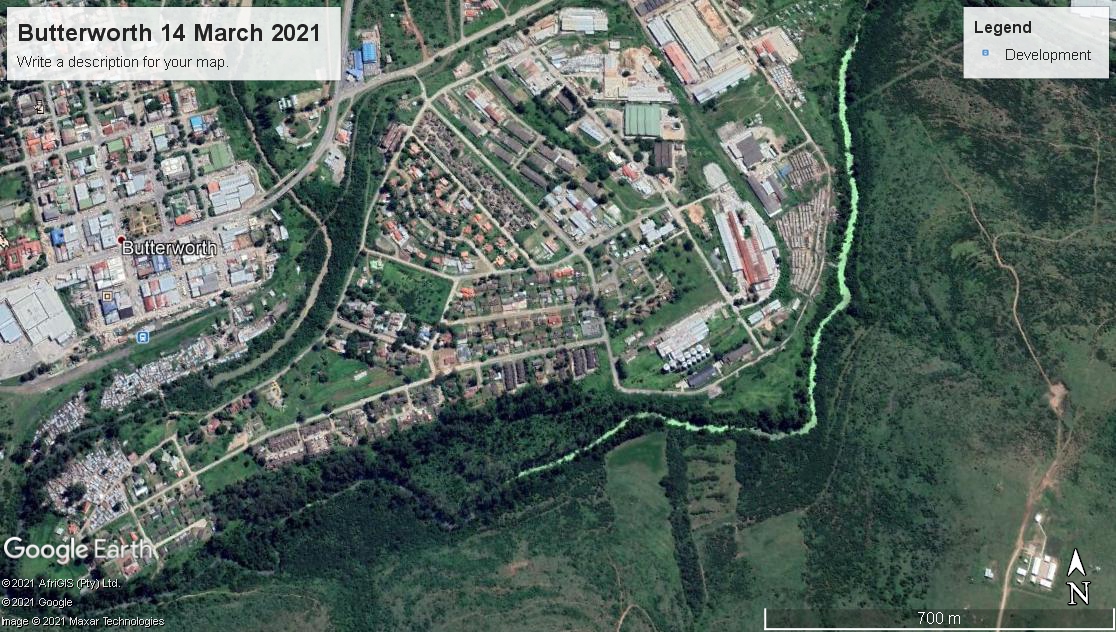

“I remember there was a time we found pigs that had died,” she says in her mother tongue, isiXhosa. She and her neighbours believed it was due to the pollution of the Gcuwa River, which they rely on as a water source. Sewage and grey water flow through the streets and a Google Earth image shows the water flowing past the temporary relocation area stained luminous green from an unknown pollution source.

Although Samka and her neighbours have access to municipal standpipes situated throughout the settlement, the safe drinking water does not flow out the town’s taps for days, sometimes weeks, at a time. They are forced to use the river for washing and drinking water.

With no other easily available water source, the death of the pigs did not stop them from using the river; they merely ensured that they boiled it before using it for drinking or cooking.

But the cost of electricity or fuel for boiling water is prohibitive for Samka, as it is for many of her neighbours in a municipality with an employment rate of 16.9%.

The river receives contaminated water and sewage from the informal settlement and town as it flows past Samka. Then it picks up a further 6 million litres of poorly treated or untreated wastewater effluent per day from the treatment plant a few hundred metres downstream.

Amathole District Municipality spokesperson Nonceba Madikizela-Vuso admits the water in the Gcuwa River as it flows past lower Butterworth “is definitely not safe to drink” due to waste emanating from the town itself. However, she denies that the quality of effluent from the treatment plant added to the pollution levels, saying the effluent was treated with chlorine.

But data on the Iris dashboard show that during 2020 the Butterworth plant consistently and drastically failed to meet minimum standards for microbiological, chemical or physical compliance of its treated effluent.

The plant’s failure is ongoing despite award-winning reporting in 2019 by Daily Dispatch reporter Bongani Fuzile that revealed independent tests showing 540,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) of E.coli per 100ml of water downstream of the town. The minimum standard is 1,000 CFUs per 100ml.

When asked what had been done following the Daily Dispatch’s reporting, DWS spokesperson Ratau said: “The department conducted an investigation within the Butterworth area following complaints received of suspected water pollution… and results confirmed that the water used by the community of Cuba in Butterworth is not from sewage spillages, rather underground seepage water.”

Ratau said that DWS has issued a notice of intention to issue a directive to the local municipality for the failure of sewage pump stations in Butterworth potentially impacting negatively on Gcuwa River: “The department continues to engage the municipality concerning possible solutions to the presence of pollutants as well as the social issues (informal squatter settlements) affecting the Gcuwa River.”

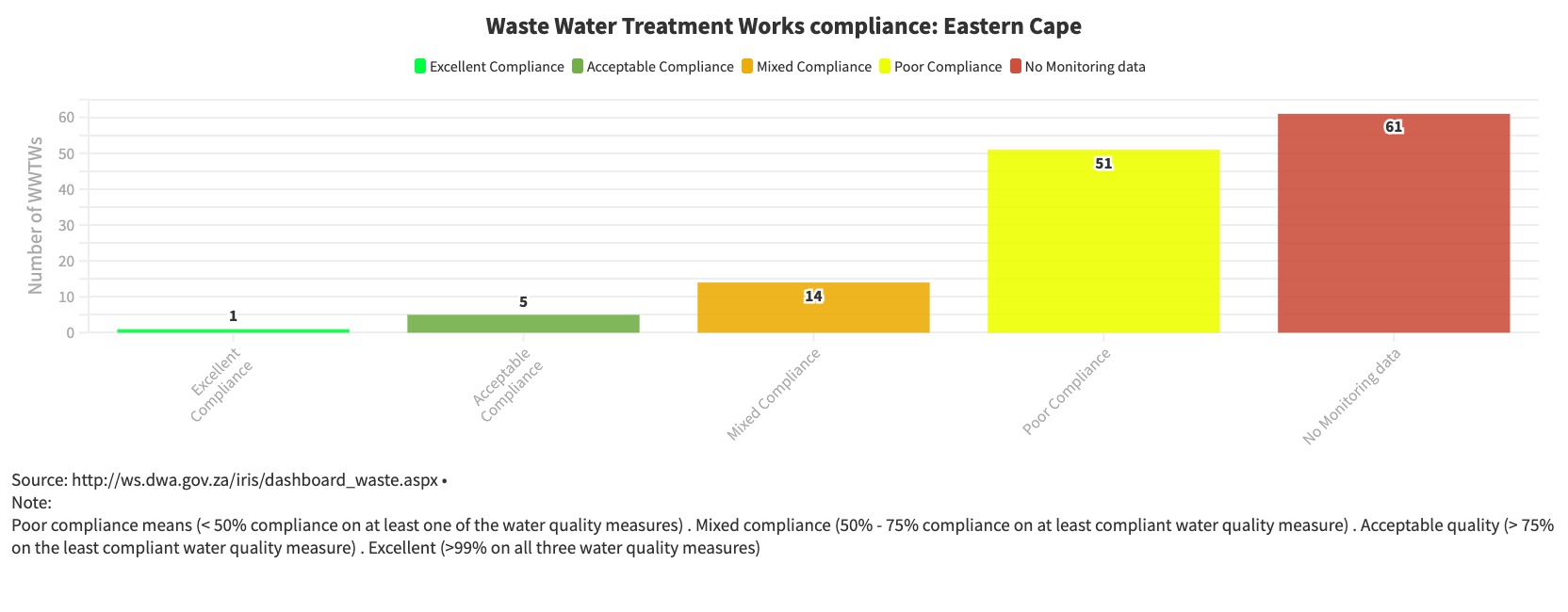

Butterworth’s sorry story is echoed across the Eastern Cape: 85% of the province’s 132 wastewater treatment plants do not meet minimum effluent guidelines on a regular basis.

Read here for a more detailed view.

The pollution of the Vaal

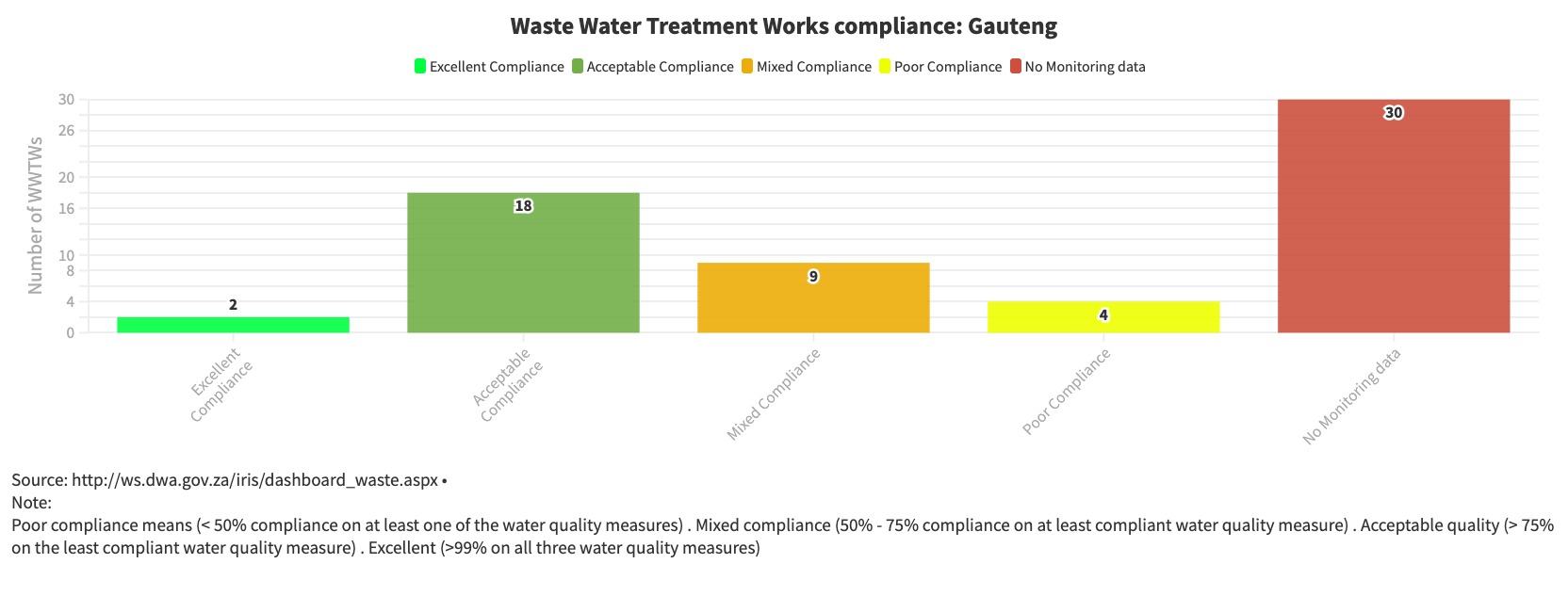

About 950km north of Butterworth is South Africa’s economic hub, the Gauteng province, and its largest city, Johannesburg.

Established in 1886 following the discovery of gold along the Witwatersrand hills, Johannesburg, unlike major cities around the world, is not situated at a water source. Its water comes from the Vaal Dam, about 100km away.

The Vaal River is South Africa’s third-largest river and has, for years, received about 150 million litres per day of poorly treated, and in many cases, raw sewage from the industrial towns situated along its banks.

A recent report by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) on the sewage problem in the Vaal River was released in February. It revealed that 19 million people who rely on the river for drinking, domestic and commercial use are affected by the pollution.

The SAHRC initiated an inquiry as continued failure by multiple levels of government to address the issue has led to the pollution becoming a human rights issue. The commission recommended that government officials should face criminal charges.

According to the report, the wastewater pollution emanates from wastewater treatment works in the Emfuleni municipality, south of Johannesburg and encompassing the industrial towns of Vereeniging and Vanderbijlpark situated alongside the Vaal River and Rietspruit, which is a direct tributary.

Following media reports on the pollution caused by untreated wastewater, the commission conducted a site inspection in September 2018 and identified a situation similar to Dunoon in Cape Town. They found “raw, untreated sewage flowing in the streets, homes, graveyards and also flowing into the Vaal River, the Vaal Dam, the Barrage and the Rietspruit (referred to collectively as “the Vaal”) (sic). The inspectors also discovered “children swimming in, and consuming, polluted waters in the area of a school”.

The Emfuleni municipality, situated within Gauteng, conceded the pollution was due to its failure to maintain wastewater infrastructure. But, the commission noted in its report, the national DWS failed to hold the municipality to account, as it is required to do by national legislation, despite the pollution being ongoing for years.

“In the absence of timely and effective response from the multiple spheres of government, Gauteng’s most vital water resource may very well have been irreparably damaged,” states the report.

Read here for a more detailed view.

Here, though, the data may be questionable. The Iris dashboard data show that Leeuwkuil, one of the four treatment plants in Emfuleni, achieved almost 100% compliance across indicators in 2020. But the commission report notes that Leeuwkuil was one of the wastewater treatment plants prioritised by the South African National Defence Force when its engineers were brought in as an emergency measure in 2018 to try to curtail the pollution. This brings the veracity of the data into question: by itself, it indicates a sufficiently functioning wastewater treatment plant surrounded by failing infrastructure, which is unlikely to be the case.

Additionally, independent testing by non-government organisation AfriForum found Leeuwkuil failed minimum standards from 2017 to 2019, the last year their test results are available. This means even the treatment plants that seem to be meeting minimum national wastewater effluent guidelines on the Iris dashboard require further investigation.

The tip of the iceberg

The failure to properly treat sewage is not just an environmental issue. It’s also a health disaster in the making.

Cheryl Shultz, IT Project Manager in the DWS’s macroplanning directorate, says South Africa’s effluent quality guidelines measure microbiological compliance (levels of E.coli bacteria), chemical compliance, which refers to “Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Ammonia, Nitrites and Nitrates, Ortho-Phosphates, etc.”, and physical compliance, which refers to pH, suspended solids and electrical conductivity.

But the standards against which these indicators are measured are themselves insufficient and have been under revision since 1996, says Dr Jo Barnes, senior lecturer emeritus in the Division of Community Health at Stellenbosch University.

Barnes believes there is no political will to implement higher standards. She explains that there are direct and indirect human health impacts of coming into contact with untreated or poorly treated sewage.

The direct impact of contact with sewage can result in gastro-intestinal illness, ear, nose or threat infections which manifest after a 24-hour incubation period. It is during this incubation period that people who have become infected return to school or work and infect others.

The indirect effects, she says, are much more frightening and are ignored by authorities.

To begin with, E.coli is largely an indicator organism: it points to the presence of other pathogens in the water.

“E.coli stands for all the pathogens, the whole book of micro-organisms,” says Barnes. These include Rotavirus, Hepatitis E, and Norwalk virus, Salmonella, and the fungus Candida.

But E.coli is a poor indicator, she says, as it dies off quickly; low E.coli levels, then, do not necessarily mean the presence of other pathogens is low.

The poor treatment of wastewater is also contributing to what she terms the “silent pandemic” of antibiotic resistance. If wastewater is poorly or inadequately treated with chemicals such as chlorine (one of the chemicals measured in the chemical compliance indicator), then it only kills the weaker micro-organisms. The stronger ones survive, creating generations that are increasingly more difficult to treat.

“We are slowly running out of drugs for treatment,” Barnes warns.

Particularly in large urban areas, wastewater is not just domestic sewage. It also includes industrial and hospital wastewater – and even treatment that measures up to national minimum standards almost certainly can’t eliminate these from the effluent released back into the environment.

“What keeps me awake at night is when we mix industrial effluent with human sewage,” says Barnes. “What is going to happen to the pathogens as they mix with thousands of chemicals from factories?

“We don’t know what happens when chemical cocktails hit microbiological cocktails.”

Everyone is affected

The DWS is well aware of the nationwide failure to properly treat wastewater.

The latest iteration of the National Water and Sanitation Master Plan was published in October 2018 and quantifies the extent of infrastructure failure and resultant pollution.

The report opens with this statement: “South Africa is facing a water crisis caused by insufficient water infrastructure maintenance and investment, recurrent droughts driven by climatic variation, inequities in access to water and sanitation, deteriorating water quality, and a lack of skilled water engineers. This crisis is already having significant impacts on economic growth and on the wellbeing of everyone in South Africa.”

The document states that over a 12-year period, between 1999 and 2011, “the extent of main rivers in South Africa classified as having a poor ecological condition increased by 500%, with some rivers pushed beyond the point of recovery”.

Additionally, more than half of all wetlands, which are crucial environmental resources, have been lost. Of those that remain, a third are “already in poor condition”.

A rapidly growing and urbanising population, coupled with the climate crisis driving the country to a warmer and drier future, also means there will be less water available. Current trends point to a 17% deficit of water availability and water needs by 2030.

The master plan sets out a detailed list of actions needed to stem pollution, conserve and protect environmental resources, and repair and maintain ageing infrastructure, all requiring R33-billion more per year than currently budgeted. Deadlines have been attached to these actions, with 14 such actions due to have been implemented by 2020. Questions sent to the DWS asking whether implementation had indeed taken place received no response despite a follow-up call and the questions being resent.

World-class city’s rivers run with sewage

Christina Malgas tries to quell the constant presence of sewer water running along the kerb outside her front door in Dunoon, Cape Town, by sweeping it towards the nearest stormwater grate. (Photo: Peter Luhanga)

Back in Cape Town, Christina Malgas aims her small can of air freshener in a futile attempt to mask the seemingly insurmountable stench. She knows that city authorities have consistently blamed residents for disposing of foreign objects in the sewer system. But she’s sceptical. Official state-built houses like hers are supplied with wheelie bins to discard their rubbish for collection by the municipality.

“We [who own state-supplied housing] don’t dump in sewers. If we dump, these things will cause blockages and sewage will overflow into our homes. So, why should we dump in there?”

She concedes that people who live in backyards (informal shacks owners of formal houses erect in their backyard and rent out) may dump rubbish into sewers and stormwater drains. There are also thousands of people who live in informal settlements surrounding Dunoon who may illegally dispose of waste into sewers.

Xanthea Limberg, the City of Cape Town’s mayoral committee member responsible for overseeing informal settlements, water and waste, has stated there are up to 400 sewage spills reported across the city daily. Some may be repeat reporting, whereas other spills may go unreported. The City’s recent Inland Water Quality Report found that 24% of these overflows and spillages are caused by maintenance issues like collapsed pipes and root growth. The remaining 76% are due to the illegal disposal of waste in sewers.

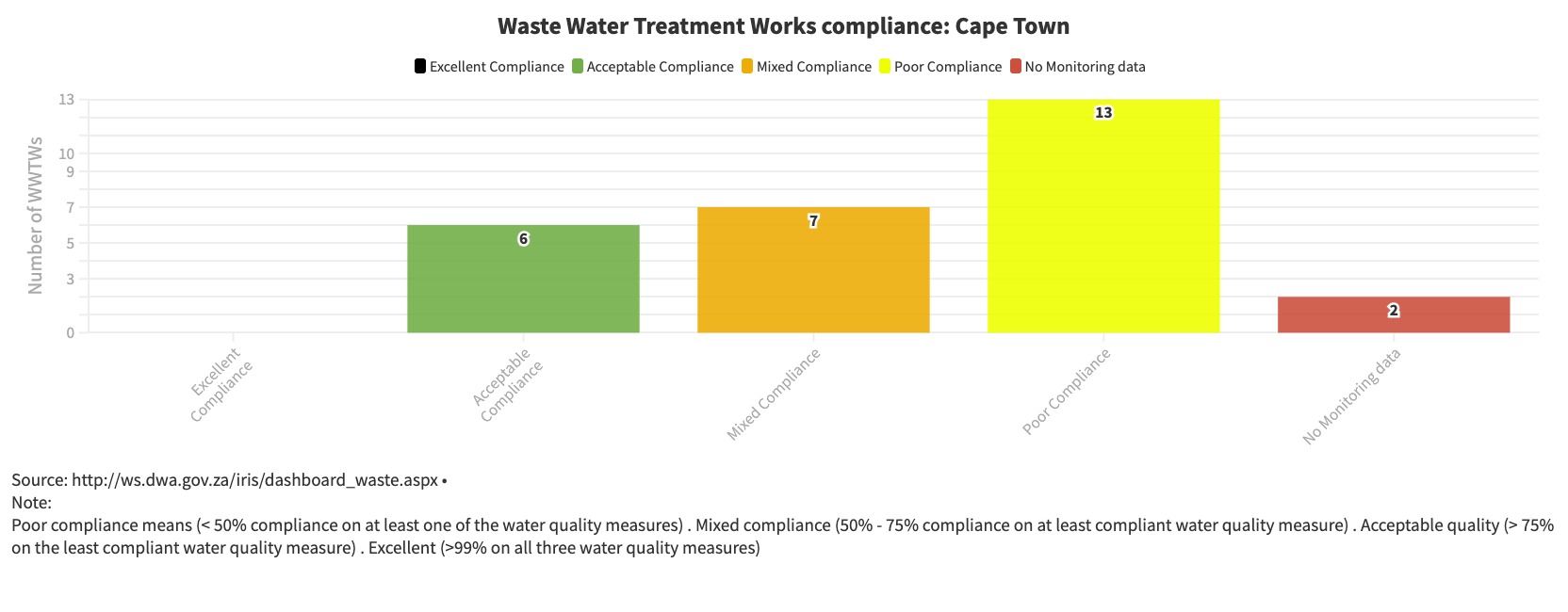

Away from its busy streets, largely unseen, the Iris data show that Cape Town’s wastewater treatment plants pump hundreds of millions of litres of almost untreated sewage into its rivers and oceans each day. This has caused parts of the city world renowned for its natural beauty and the biodiversity of its flora, to literally stink.

Read here for a more detailed view.

Estuaries that are crucial fish nurseries have been ecologically devastated. The City’s own water-quality report states almost half its river systems are so polluted that canoeing on them would be a health hazard.

One of Cape Town’s most polluted water bodies is the Diep River estuary, which receives up to 47 million litres of effluent from the Potsdam plant per day. Lack of proper wastewater treatment has hit the environment so hard that the Environmental Management Inspectorate last year issued the City with an order to clean it up – failure to do so carried criminal charges. Drinking water supply is also compromised.

Recreational water bodies are periodically closed to the public due to sewage spills, and the City pumps about 40 million litres of essentially raw sewage and industrial wastewater directly into the ocean every day from three marine outfalls. The only treatment this wastewater receives is that it goes through a 3mm sieve to remove solids such as plastics and grit.

Scientists from local universities have studied how this wastewater, which includes pollutants from the light industry, as well as antibiotics and pharmaceutical compounds from hospitals such as the Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital in the central city, is affecting the marine ecosystem, including accumulating in molluscs and seaweed.

The economic, health and environmental impact of sewage pollution, says Barnes, who was one of the authors of this and other studies, is “grossly, grossly underrated”.

Meanwhile, millions of South Africans live with the daily reality of contaminated water. Some have given up hope of the situation ever improving.

“We have accepted the conditions of living here since we do not know who is going to rescue us,” says Samka outside her home in Butterworth’s temporary settlement.

“We have made peace with these conditions.” DM168

Sidebar: Calculating the wastewater data

The Iris dashboard is a development of the national department’s Green Drop programme initiated in 2007 as an auditing tool to assess wastewater treatment across the country.

There are three indicators of effluent quality contained in the data: microbiological, chemical, physical.

The Green Drop reports provide a weighted score for wastewater treatment works (WWTWs) based on these and other factors, but as these weightings were not available to use, we adopted a simple indicator which corresponds to the Iris dashboard legend, to determine whether WWTWs were failing to adequately treat wastewater.

Failing WWTWs: <50% for all three indicators, including no monitoring data submitted.

Poor compliance: <50% on at least one effluent-quality indicator.

Mixed compliance: 50% – 75% on the least compliant effluent-quality indicator.

Acceptable compliance: >75% on the least compliant effluent-quality indicator.

Excellent compliance: >99% compliance on all three effluent-quality indicators.

This investigation was produced in collaboration with the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism and Code for All, with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy.

Video by Peter Luhanga and Nombulelo Damba.

Visualisations and additional research by Nompumelelo Mtsweni.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thank you for this in-depth analysis of the reality faced by many South Africans and the dangers associated to a sustainable future.

I often see children defecate and play in puddles of grey water at the “Plot 175” informal settlement, here in Kameeldrift East, Pretoria(Ward 87). This is a sad state

And?

This article deals with many truths…mainly:

– the failure of Racist BEE policies where competent people have been sideline because of their skin colour

– the lack of civic will in communities and informal settlements

– Urban overpopulation encouraged by Gov Grants.

In my opinion.

Maybe those Cubans will fix it

Failing waste water treatment, failed post office, municipalities bankrupt, health service in shambles. Mr President are you asleep?

ANC 100% to blame – the Minister should be in jail

Blocked sewers in Dunoon are hardly an example of failed sewerage treatment. By your interviewee’s own admission, garbage from informal settlements around Dunoon may end up in the sewers, and cleared sewers block again within days. Why? Negative bias here towards the City of of Cape Town.

Obviously. It’s run by the DA, so it must be bad.

There are enough capable Engineers, Wastewater specialists and specialist Wastewater Contractors to address, repair and maintain the infrastructure. Authorities have 90 days to evaluate and award these projects. 12 months and longer for projects to be awarded and we import Cuban Engineers !

Apocalyptic conditions, the only ones smiling are the suppliers of top of the range Merc AMG and Range Rover.

Let’s not forget that this huge quantity of untreated waste water is being wasted by dumping it in the rivers and sea. Properly processed, it could be recycled for reuse.

Is or has anyone other than Jan Van Riebeck been held accountable?

What a disgrace this government is at every single level with not one ANC appointee being able to do the job that they are paid to do and yet no one is ever accountable. The dream of a better life for the majority of people remains just that.

“24% of these overflows and spillages are caused by maintenance issues like collapsed pipes and root growth. The remaining 76% are due to the illegal disposal of waste in sewers.”

Pipes don’t just block themselves. The one variable in this is people.