REFLEXIONS: READING IN THE PRESENT TENSE

‘If this is a Man’; ‘If I was God’

Locked down, locked in, many of us have had time to read more books than ever before. Readers, passionate about their own favourite books, are curious to know what writers have been reading during this bleak and lonely period. What was already on their shelves, what did they borrow, buy or read online?

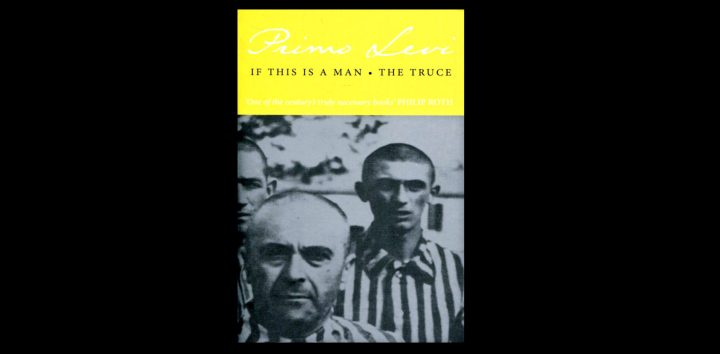

In this series, Reflexions: Reading in the present tense, established and younger writers and other creative artists will reflect on a text that moved them, intellectually engaged them, frightened them or made them laugh. Our reviewer today is Drew Forrest who considers If This is a Man, by Primo Levi.

***

Once in a while, the conjunction between the book one is reading and an event in the real world strikes vivid sparks.

I was halfway through Primo Levi’s searing account of his 11 months in Auschwitz, If This is a Man, when the US Capitol was stormed by fanatical worshippers of Donald Trump, many wearing Nazi regalia or from openly anti-Semitic groups like QAnon. One of the invaders wore a T-shirt with a “Camp Auschwitz” slogan, above a skull and crossbones and the pitiless camp motto, “Arbeit macht frei” (work brings freedom).

There are now more than 150 neo-Nazi, white nationalist, Holocaust denial and similar hate groups in the US, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks the American ultra-right. They grew by more than 50% under Trump’s presidency.

Like Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Levi’s account is prison literature and a record of human survival in extreme conditions. But centrally, it is an exploration of the mysterious collective pathology of fascism.

An Italian-Jewish industrial chemist, Levi was one of 80,000 slave workers who toiled at IG Farben’s synthetic rubber plant in the Auschwitz complex, initially as a labourer and in the months before he was liberated by the Red Army, in the laboratory. A nameless Häftling (prisoner) with the serial number 174517 tattooed on his left arm, he became a “miserable and sordid puppet”.

In one telling incident, he feels himself sink into the ground with shame while in the presence of three young German women lab assistants, rosy-cheeked, blond-haired and attractively dressed. “They never speak to us and turn up their noses when they see us shuffling … squalid and filthy, awkward and insecure in our [wood and wire] shoes”. Levi asks one of them a question; his blood freezes when, with an annoyed expression, she turns to her friend and he makes out the word “Stinkjude”. Later, in chatter typical of offices everywhere, he overhears one of the women say: “Only two weeks and it will be Christmas again; it hardly seems real, this year has gone by so quickly!” A year which for Levi meant forced labour, starvation, beatings – and frequent selekca (selections) for the gas chambers

Marxists tend to view fascism as a ruling-class ploy to divide workers. But as Levi’s contact with the lab assistants shows, it is a popular phenomenon. Big business profited handsomely from the slave economy, but Nazism was not an ideological imposition from above. Relatively few Germans actively resisted it – and the mass of German workers remained Hitler’s loyal allies to the end.

Political historian Isaac Deutscher suggests that proletarian fascism is compensatory – it offers those at the bottom of the pile an even lower stratum of ideological inferiors to dominate and victimise. It also offers a refuge and vehicle of redress for the failed, embittered and socially inept. The Häftling kapo (commander) of Levi’s chemical unit tells them that if they, as Intelligenten, think they can make fool of him, a pure German, he would … and he cuts the air with his finger in a menacing gesture.

The title of Levi’s work is a floating hypothetical, inviting the subordinate clause “how could this happen to him?”

To the young women in the lab, he is invisible; the nurse in Ka-Be, the infirmary, “points to my ribs to show the others, as if I was a corpse in an anatomy class” and presses his pale flesh to show the indentations “as if it was wax”. Alex the kapo cleans his grease-covered hands by casually wiping them, front and back, on Levi’s clothes. He has been reduced to a thing, in a process that deadens normal sympathetic responses to those “crushed against the bottom”. Fascism systematically denudes its victims of subjectivity.

One saw something of this in the assault on the Capitol, when the neo-Nazi hard core tried to track down members of “the Squad”, a group of radical black lawmakers, all women, that the far-right media and Republican ultras had consistently objectified as foreigners and terrorists. There was more than a whiff of kidnapping and rape in the air during the invasion. Squad member Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who from a hiding-place heard hammering on her office door and a male voice shouting “Where is she?”, linked the attack to her past experience of sexual assault.

Fascists have a morbidly enlarged need for order and hierarchy – including leaders they can idolise and underlings they can lord it over – and are intensely preoccupied with the subordination of women. On the internet, in neo-Nazi threats and fantasies, the sexual humiliation of left-wing female politicians is a pervasive theme. This was institutionalised in Auschwitz and other concentration camps: Block 29, whose windows were permanently closed, was the camp brothel. For the sole use of Reichsdeutsche, racially pure Germans, it was served by Polish women prisoners.

The fascist idea of a naturally ordained ranking of races was mirrored in the organisation of Auschwitz, where ordinary Jewish inmates, “the slaves of the slaves”, were on the lowest rung. Above them stood the Jewish Prominenten or trusties, from kapos to Scheissminister (latrine superintendents), and higher up the ladder the German Prominents, mainly criminals.

Levi presents the camp as the model fascist order, a universe of insatiate needs where, under the iron law of natural selection, each individual must fight for life against the rest. Normal moral imperatives – including loyalty to one’s comrades and solidarity of the oppressed – no longer hold. “Survival without renunciation of any part of one’s moral world … was conceded to very few superior individuals, made of the stuff of martyrs and saints,” he writes.

After coming through the great selekca of October 1944, Levi sees one of the older prisoners rocking furiously to and fro on his bunk in a prayer of thanksgiving at being spared – in full view of a young man who knows he has been earmarked for the gas chamber. “Does Kuhn not understand that what happened today is an abomination … which nothing at all in the power of man can ever clean again?” Levi storms. “If I was God, I would spit at Kuhn’s prayer!”

If This is a Man should be read not only as an anatomy of fascism and a personal chronicle of infamous crimes. After his untimely death, Levi was lamented as one of Italy’s foremost 20th century writers.

His Auschwitz memoir is far from being a testament of gloom, leaden and dispiriting. As one critic said of TS Eliot’s early verse, it has a kind of glowing despair.

Like a medieval canvas, his darkling landscape teems with grotesques and saints: the mad, “physically indestructible” dwarf Elias, who thrives on camp life; Doktor Pannwitz, the blond, manicured Aryan who discusses chemistry with prisoner 174517 in his shiny office; Lorenzo, the civilian worker who, over months, smuggles bread and some of his rations to Levi, writes a postcard to Italy for him and brings back the reply. There is dark comedy in the description of the informal market in one corner of the camp, where specialists in kitchen theft wear “jackets swollen with strange bulges”.

And there are redemptive passages. Despite the foul water and absence of soap, the prisoner Steinlauf washes every morning and dries himself with his jacket. He explains that not to do so is to become less than human, and that slaves – stripped of every right, exposed to every insult, condemned to certain extinction – possess one inalienable power: to refuse their consent.

Given the global resurgence of the far right, Levi’s questions about the heart of darkness are as relevant as ever. How was the bestiality of Auschwitz possible in a country of such economic, technical and cultural sophistication? How did racial prejudice, a human commonplace, balloon into an exercise in cold-hearted murder on an industrial scale? Why, given the inevitability of death, was there so little resistance?

For a man of Levi’s tender sensibilities, the deepest and most lasting injury seems to have been his shame over the compromises he was compelled to make to stay alive.

There is a powerful account in If This is a Man of the hanging of a mutinous prisoner accused of sabotaging a crematorium, which the assembled inmates are made to witness. Before he drops through the trapdoor, he shouts: “I am the last man, comrades!” The cry strikes the human core in each of the Häftlinge. But “bent and grey, our heads dropped”, they are too cowed and broken even to murmur assent.

“Here we are, docile under [the German] gaze”, Levi writes in bitter self-reproach. “From our side you have nothing more to fear; no acts of violence; no words of defiance; not even a look of judgement.”

Having struggled so hard for life, Levi was to plunge down a stairwell in a Turin apartment block in 1987 in an apparent suicide.

Another Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel, remarked that the great writer had died in Auschwitz, 40 years before. DM/MC

Drew Forrest has been working as a journalist for 40 years, with stints at Business Day, Mail & Guardian, Times of Swaziland and the amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism. He has been a deputy editor, political editor, business editor and labour editor, among other positions. Author of a book on cricket, “The Pacemen” (Pan Macmillan 2013), he has also edited a number of non-fiction books. He is currently the managing partner (editorial) of IJ Hub, a regional training offshoot of amaBhungane.

Thank you, Drew. Your review, though heartrending, was beautiful (three of my father’s siblings were murdered in Auschwitz).

A most timely (and incisive) reminder of how it could happen again and of our responsibility to make sure it doesn’t. Thank you, Drew.