LOVE, UNSTOPPABLE

The love story with the mother I never knew

‘I want the pain that I experience to somehow be meaningful. And part of its meaningfulness is to ensure that the story never dies,’ says Jacki Mpondo-Hendricks as she recounts her mother’s trailblazing love and the joy and sorrow that accompanied it.

As told to Karel van der Vyver.

The story I can tell is one of love, yes, but it is also a story of lost love, of the love of a mother I never experienced. But perhaps I’m getting ahead of myself, I should start at the beginning.

I grew up in the township of New Brighton in Port Elizabeth. Growing up, I believed my mother was my aunt and my father was my brother. My grandparents raised me, and I thought they were my parents.

I was eight years old when my mother died. I can’t remember my grandparents ever telling me, I just heard rumours on the street. People would approach me and offer their condolences and I couldn’t understand why the death of a far-off relative would garner such attention and sympathy for me.

As I grew older I began to piece things together, broken images of a family I thought I knew, slowly glued back one by one into the real story. I remembered my mother visiting our house five weeks before she died; then, she made peace with my father and his family. She came to see me, which to this day is the last recollection I have of her. I feel she might have had an intuition that something might happen.

Photo supplied by Jacki Mpondo-Hendricks

Why was my mother not there to raise me? Like me, she was born and raised in New Brighton. She studied and qualified to be a nurse. She married my father there when she was still young, but the bright lights of Johannesburg always lured her. She found life in Port Elizabeth too mundane. And so, in 1976, she left me, her husband, her town and moved to Johannesburg. I was six months old.

But my mother was no ordinary person.

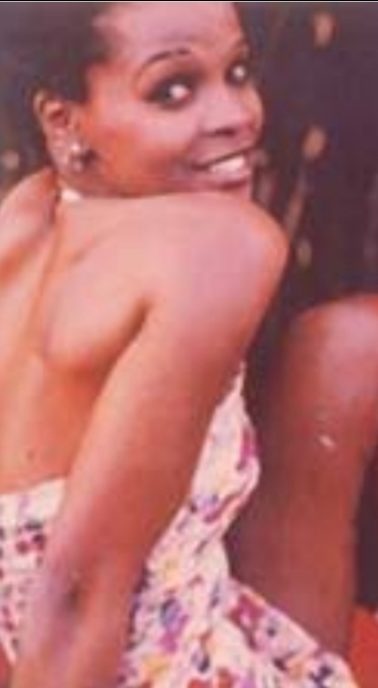

Her real name was Nobanthu Faith Mpondo, but the name she chose to use was Bubbles, Bubbles Mpondo. The brother of one of her closest friends named her Bubbles because whenever she entered a room she exuded this addictive, refreshing energy, and she was very, very talkative.

Bubbles started a modelling career in Johannesburg, auditioning for and winning the Miss Soweto title and many other modelling competitions. Soon she was offered an international modelling contract and also became the face of various famous brands.

She rocketed to the top of the modelling world. Bubbles became a renowned model and beauty queen, gracing the covers of magazines. I’m told that when she walked down the street traffic would stop. And when she entered a room she immediately became the centre of attention.

She was no ordinary person.

She inspired and represented black beauty in the 1970s. Her skin was very dark and she fully embraced it; she believed in natural hair. And when she did braid, she did it to celebrate the African beauty aesthetic.

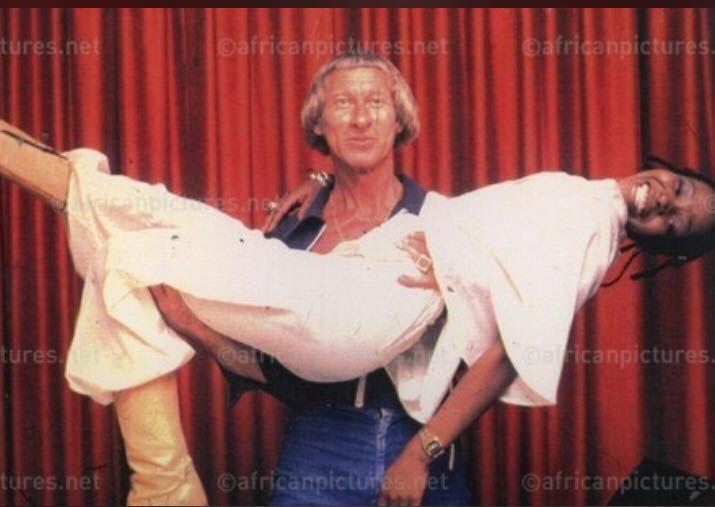

Photo supplied by Jacki Mpondo-Hendricks

Her fame became so widespread that it even reached Robben Island. One of the political prisoners had a photo of Bubbles stuck to the wall, which encouraged him during the difficult times to remain hopeful that he would get out and possibly meet her.

It was in Johannesburg that she met Jannie Beetge. He was a world-champion bodybuilder and founded the first well-known gym in the Johannesburg inner city.

Beetge came from a very entrenched National Party family.

From what I could gather he saw Bubbles when she was walking down the street in downtown Johannesburg and it was love at first sight. It was an obsessive love that they shared… And soon he asked her to move in with him and they lived together.

But Bubbles was famous and the relationship started to receive media attention; it was featured weekly in all the newspapers. It even attracted international interest. Unlike other interracial relationships during that era, they flaunted theirs; they were unapologetic about loving each other.

Photo supplied by Jacki Mpondo-Hendricks

The relationship was, of course, completely illegal. There were police officers who specialised in bringing interracial couples to book and they were tracking Bubbles and Beetge all the time.

The law was not the only thing that interfered with their love. They faced social stigma, too, because as much as it was taboo for a white man to date a black woman, it was also taboo for a black woman to date a white man.

Jannie would not emerge from the relationship unscathed. His family was so appalled by the relationship that they disowned him. His brother also publicly denounced him. On one occasion they were taken to trial after another brush with the Immorality Act. While out on bail they announced their intention to get married. They were found guilty of the crime and given an eight-month suspended sentence, but it did little to stop the relationship.

When the marriage permit was turned down, since interracial marriages were illegal, they decided to move to Europe to pursue their relationship. From what I heard they were planning to move to Paris, via Botswana.

But it all ended on 24 August 1978.

They were both found dead in their apartment in Johannesburg. My mother had been shot between the eyes. Once. And then Jannie shot himself.

She was buried in an unmarked grave.

Many years later, I was approached to take part in a documentary series called Love Stories, for which they shot more than 80 hours of footage, covering the life and love of Bubbles and Jannie.

That’s when a different possible narrative began emerging – that their deaths were the result of an operation by the security and intelligence services. They had a clear motive for this – killing them ended the problem; their love was trouble and an embarrassment to the country, while it also exposed the immorality of the Immorality Act.

No one can ever fully know what happened in that room; it haunts me to this day that I will never fully know how and why my mother died.

But their love story was far bigger than just two people; it was a story that was meant to disrupt the status quo. Love was supposed to conquer.

My mother and I

And the love story between me and the mother I never knew? I’m still processing all the emotions. It’s a lifelong process. It’s not something that you just recover from, like the flu. She is part of my DNA. She is my mother. She will be with me until I die.

Photo supplied by Jacki Mpondo-Hendricks

I want the pain that I experience to somehow be meaningful. And part of its meaningfulness is to ensure that the story never dies. I think part of the key to my healing will be in finding the answers to the unanswered questions.

For me, one of the painful things to deal with is the issue of desertion, understanding the choices she made. I always wanted to know whether she considered how her choices affected me as her child.

She publicly denied that she had children, since a supermodel could not have children in those days. But it was not just about denying me, but failing to live up to her role as a mother. So part of the healing process was having insight into this larger-than-life woman, who was meant to be my mother but never was.

I also wish I could get a better understanding of Jannie’s perspective of the relationship. And I wish one day I could have a conversation with Jannie’s children, who probably experienced emotions similar to mine.

I think that for every child who is the product of someone who had such an impact on history, it’s difficult to come to terms with the fact that you are not them, but of them.

However, when I began to put into perspective the impact their relationship had on the fight against apartheid, I realised that the sacrifice of the love between a mother and a child was possibly worth it.

Now, having to explain to my kids why their grandmother is not around is a burden I will carry to my death. But I want her spirit, which is within me, to be kept alive. Because when she was alive she was a game changer. When she was alive she was a trailblazer. DM/ML

Jacki Mpondo-Hendricks is the first black woman president of the Johannesburg Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I applaud your positive way of dealing with such a tough central aspect of your life.