We know that Maverick Citizen respects and protects the crucial role of the South Africa Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) in ensuring efficacy and safety of medicines. However, where the need is urgent and immediate, we also think that public debate of the evidence on which its decisions are based is also important. The use of Ivermectin is a case in point.

Here, a frontline intensive care doctor explains why he thinks there are strong medical grounds to make ivermectin available for compassionate use.

Between 21 December 2020 and 9 January 2021 South Africa recorded a further 8,100 deaths from Covid-19 and a total of 292,260 new cases. This means we have had: an average of 13,917 new cases daily and an average of 386 deaths per day.

I have chosen 21 December because that is when the Rapid Review by the National Essential Medicines List Committee (NEMLC) Covid-19 subcommittee recommended we wait for more large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to be published to decide whether ivermectin is appropriate for South Africa.

The scientists who put this review together need to be commended for producing it in a short period; that document became the basis for continued objection to the immediate granting of permission for ivermectin use for patients with Covid-19. Their document is at least slightly better than the initial from SAHPRA, released on 22 December, and whose improved 6 January statement is here.

But, in my view the Rapid Review was inadequate. It is also unacceptable, considering that since its publication there has been enough outcry and enough information has been shared on what it missed. More than three weeks later they have not reviewed their recommendation, which the Department of Health (DoH) continues to use to refuse the authorisation of this potentially life-saving medication.

It is interesting that the DoH, through its Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC), released a follow-up memo, dated 7 January 2021. This memo acknowledges that the “unregulated use of ivermectin is evident in South Africa and increasing” and that, “at a community level it appears that ivermectin is being widely promoted for the treatment and/or prevention of Covid-19. There are numerous anecdotal reports from general practitioners and pharmacists of the widespread prescribing and sale of ivermectin for these purposes.”

Although this memo is a step in the right direction, it is too timid and less pragmatic about maximising on saving patients’ lives. It reaches the same conclusion that “until more robust evidence is available, the routine use of ivermectin for either the prevention or treatment of Covid-19 is not justified” while recognising that “emerging evidence must be actively sought and carefully reviewed”.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/MC-Heywood-Ivermectin.jpg)

The authors of the Rapid Review based their decision on four small studies (with 632 patients) when there were an additional seven randomised controlled studies with more patients, including an Argentinian study with 1,370 patients already registered or ongoing.

Dr Andrew Hill from Liverpool recently presented his meta-analysis data on the use of ivermectin in Covid-19, with a total of 7,100 patients from 53 available clinical trials.

Hill’s preliminary data was available when the Rapid Review was published, which brings into question the resources available to the team and the meaningfulness of their review. This information is publicly available, so it is very concerning that we have not had a “rapid” follow-up to the Rapid Review.

Why do I care?

I work at Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital north of Pretoria, the only tertiary hospital in the area, serving 1.7 million people with just 26 formal ICU beds and a single qualified ICU specialist. We have an additional 280 “isolation ICU-capable beds” which were recently upgraded with negative pressure/flow to enable us to manage a major contagious pandemic of Ebola proportions. Unfortunately, we do not have suitably qualified staff to look after patients in those beds, despite the recent employment of new nurses.

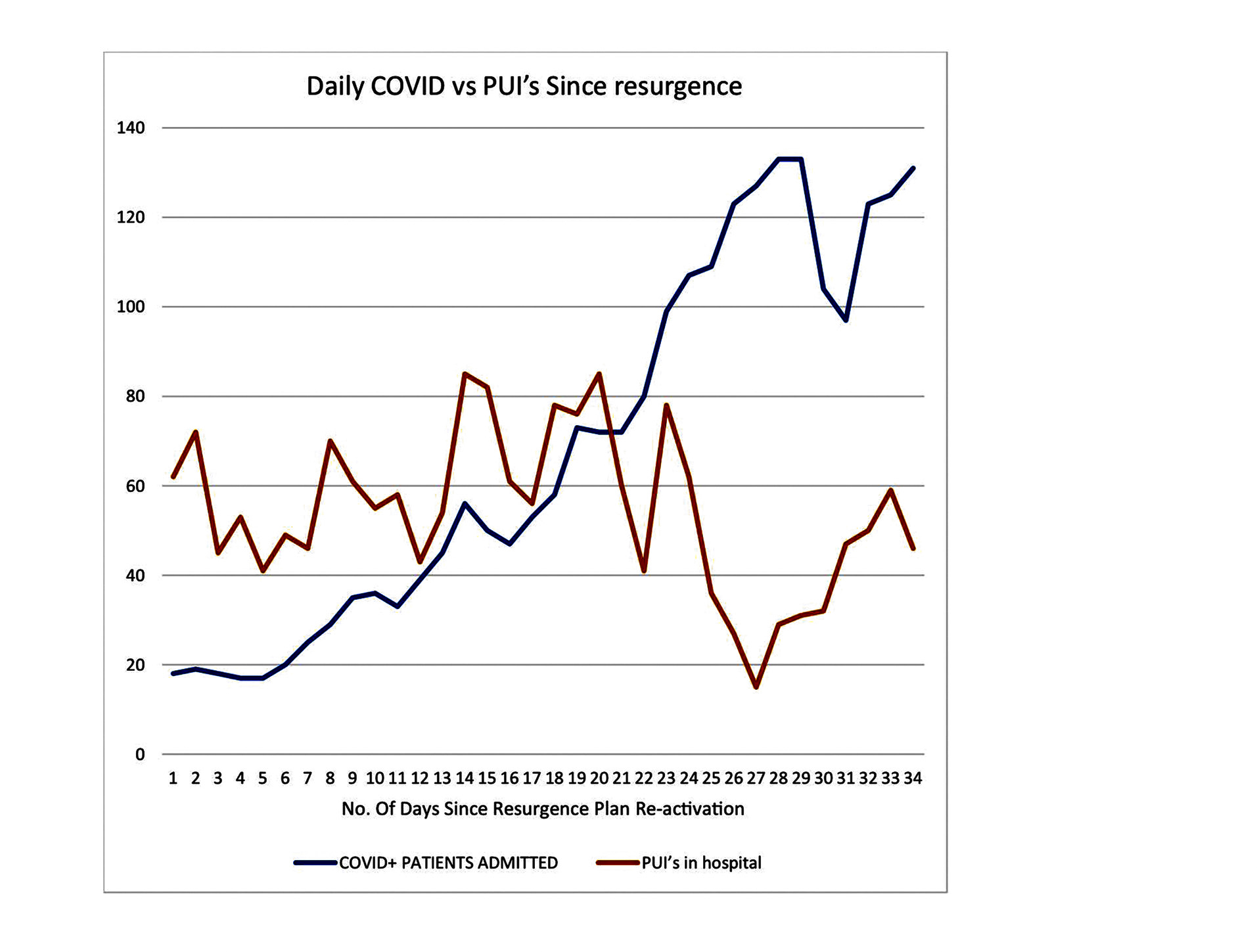

These have been our observations since 7 December 2020 when we decided to reactivate our “Resurgence Plan” (originally scheduled for 4 January 2021):

- At the end of November 2020 our admitted cases doubled from between six and eight to more than 20 in a week;

- That number increased to more than 40 by the next week and to more than 80 by 21 December. On this day we began mobilising all surgical departments to free their beds to accommodate a projected unmanageable surge;

- The patients we were seeing with this resurgence were, worryingly, younger (40s) and sicker than our first surge;

- By 28 December we had 110 admitted patients, and 133 by 4 January 2021 (a 17-fold increase in fewer than 30 days);

- We were losing an average of four patients a day, including persons under investigation (PUI) with results unknown and Covid-19 patients (more than two per day);

- The number of patients requiring oxygen grew exponentially compared with the first surge.

- Our mortality for Covid and PUI patients has gone up 40-fold.

The situation at our institution holds true for the majority of state institutions except for the better-resourced “elites” – Groote Schuur Hospital (UCT), Charlotte Maxeke Academic (Wits), to a lesser degree Steve Biko Academic Hospital (Pretoria University), University of KwaZulu-Natal Academic Hospitals in Durban and Tygerberg Academic Hospital (Stellenbosch).

We and the rest of the other academic hospitals represent a lower tier of academic hospitals, with poor infrastructure, weaker administration, fewer research capabilities and poorer systems.

The district systems function on an even lower level than we do, which means if our systems are suboptimal, theirs are abysmal. They include Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital in Mthatha, Livingstone Hospital in Port Elizabeth, Limpopo Academic Hospital – Elim and Pietermaritzburg Complex.

If we are in a bad situation, then the district and secondary hospitals are in even worse positions.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions important but not sufficient

One of the things we learnt from the first surge was the limit to how effective our non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are. They are vitally important but insufficient because of the social and economic conditions in South Africa.

At the time of writing we are officially sitting at 33,579 deaths. The escalation in cases and mortalities in the past 40 days has surpassed the numbers from our initial surge. By 5 January the number of excess deaths was 83,918.

The first surge carried with it high infection numbers and very low mortality rates compared to the Northern Hemisphere countries.

The new surge, fuelled by a mutated virus, has, unfortunately, changed our landscape and it almost feels as if we are dealing with a different virus altogether. The numbers are higher, and the disease seems more intense with the preponderance of the 40-49 age group being higher and characterised by more mortalities.

Some provinces and districts that were spared during the first surge have suddenly been hit hard. Sadly, and more concerning, is that they are also the least-prepared and incapacitated provinces – they include the Eastern Cape (second surge), Garden Route (first surge), Limpopo (first surge), KZN (second surge) and parts of Mpumalanga (first surge).

We are now experiencing a more severe pandemic than we did initially, in terms of cases, and possibly a higher mortality, but we’ll only know this for certain towards the tail-end of this surge when we are able to gather data. We know there is a delay in reported mortality cases as sick patients stay in hospital longer and this number is bound to increase in the next two to four weeks.

The majority of South African hospitals have insufficient resources, the staff managing these patients often lack the means to do so, and the resources we have are limited in most settings, especially capacity for high-flow oxygen, which is the lifesaving intervention for these patients. Our interventions should always take this reality into consideration, and more resources need to be directed towards research on locally relevant projections and interventions.

It is appalling that we have such a disjointed strategy in tackling this pandemic, 27 years into our democracy. The DoH seems to be still battling to appreciate the fact that South Africa is a Third World country with a 10% First World component embedded in it. Any strategy that fails to recognise this will fail, every time. The HIV pandemic should have taught us this, but we seem to have missed the lessons.

We now find ourselves at a desperate juncture where a vaccine is our only remaining “silver bullet”, if one believes in the mythology of werewolves. But for a virus with a penchant for mutation it only takes those heavily invested in seeing a worldwide rollout of vaccines to believe that mutations will not have an impact on vaccine efficacy.

In any case, most Third World countries are a long way from universal vaccination while the virus rages, and they are facing conditions where if you are high risk and you contract Covid-19, your chances of survival are a toss of a coin (50:50 at best).

Pragmatic and rational steps to save lives

We need to be honest and find pragmatic ways of dealing with the reality we find ourselves in. We need to follow, and rapidly adopt, interventions researched and adopted by countries that have some resemblance to us.

At the beginning of the pandemic the World Health Organisation (WHO), through Unitaid, decided to investigate cheap drugs that would be suitable for Third World countries because they are readily available, have a proven track record of efficacy and a tolerable side-effect profile. The WHO-Unitaid collaboration, known as the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), is co-chaired by Health Minister Zweli Mkhize, and the therapeutic investigation arm is driven by Unitaid and the Wellcome Trust.

Ivermectin, which is an anti-parasitic (anti-helminthic) used for a variety of parasitic diseases in humans and animals, has been extensively investigated in this regard (for questions and answers about ivermectin see here). The drug is not registered for human use in South Africa, but it is in many other countries, including the US, and “off-label” use is common.

The drug has been in existence since 1975 and came to medical use in 1981. The common side-effects are red eyes, dry skin and burning skin. Its safety in pregnancy is uncertain, but it is probably acceptable for use during breastfeeding.

The most feared complication is probably the one involving the brain. Interestingly, the most recent review from a Swedish group of researchers tasked with monitoring these neurological side-effects found only 48 such reports, with only 20 having a plausible cause related to ivermectin. Their review, Serious neurological adverse events after ivermectin - Do they occur beyond the indication of Onchocerciasis, is here.

For a drug that has been dosed almost 3.5 billion times since it came to existence, these side-effects are obviously negligible. We have more dangerous drugs with way more common side-effects than ivermectin that are being used routinely, including many of our antiretrovirals that save lives.

The preliminary results from the Unitaid meta-analysis have already been presented by many people, including Dr/Professor Pierre Kory and Professor Paul Marik of the Front Line Critical Care COVID (FLCCV) Alliance, and the principal investigator of the Unitaid-funded review, Dr Andrew Hill from the University of Liverpool. The findings, from more than 50 trials including 11 randomised control trials of good quality and significant numbers, have yielded 7,100 patients, enough for a robust meta-analysis.

These were the impactful and statistically significant results from the meta-analysis in favour of ivermectin compared with a placebo. They showed:

- Faster viral clearance – an obvious marker of drug effect;

- Shorter hospital stay – a measure more relevant in resource-constrained environments;

- 48% higher rates of clinical recovery;

- An 83% increase in survival rates – the goal of most therapeutic interventions; and

- The drug was effective in all the clinical stages of the disease – prevention/prophylaxis->out-of-hospital treatment – and treatment of severe disease.

Besides the available clinical evidence from clinical trials, there are also numerous anecdotal testimonials from respected colleagues who are clinicians in the frontline and managing Covid-19 patients.

Some of the ones I have heard in a recent webinar from colleagues in Zimbabwe, which can be watched here, are:

- “It makes treating Covid-19 patients fun again.” I dare you to find any South African doctor in the frontline who can say this about treating these patients;

- “Patients with very low oxygen saturations around 60-80% are discharged within a day of admission, off oxygen.” This is in a country poorer than South Africa, with an even worse challenge of resources.

To put this into context, none of the currently available and permitted drugs has shown similar benefits:

- Steroids, which are advocated by everyone, have a very narrow window of effectiveness, with a modest 25% mortality reduction. The benefit of steroids is that they are cheap and readily available;

- The antiretroviral combination of Lopinavir/Ritonavir has been declared ineffective. With our high HIV/Aids population, this was a reasonable drug to study if it was to be effective since it is readily available with a known side-effect profile;

- Tocilizumab has been found ineffective in the large multicentre, randomised control trial by Solidarity, with a narrow window of purported benefit. The UK has authorised it for licensure and prescription in Covid-19, based on the results of the single REMAP-CAP trial. This is a drug that costs R55,000 ($3,600) for a patient course of treatment, with a modest benefit of 8.5% mortality reduction;

- Hydroxychloroquine had to be quickly withdrawn due to side-effects and no benefit on mortality; it also had a narrow window of effectiveness;

- Remdesivir is the last drug being studied by the Solidarity Trial, and is slowly also showing a lack of statistically significant effect on mortality, with a limited window of effectiveness. It also has a discouraging price tag, especially for low-income countries, of R10,000 per patient.

Source: P Marik, EVMC Critical Care Covid-19 Management Protocol

The reality is that our healthcare system is not adequate for the majority (85%) of the population because of limited resources, skills and capacity.

Reports of hospital bed shortages abound in the media. What is never broken down and explained is why there is such a shortage. A survey I conducted of private hospitals during the first wave revealed many had been running at 25-40% capacity during this pandemic, in the initial and the current surges. This is no different to state hospitals, where only 25% of hospital beds will be allocated to Covid patients and the rest remain empty as surgical services and other elective admissions are stopped.

The contributors to ICU bed shortages are:

- Staff shortages – either endemic or from current illness with Covid-19;

- Staff deaths from Covid-19;

- High-risk staff who cannot work during a surge;

- Fear that prevents staff from coming into work.

The other statistic that lacks detail is why Covid-19 patients die in South Africa.

From personal experience in our unit, through speaking to other colleagues in similar set-ups as ours and reading distress calls from doctors in the districts and lower-level hospitals, it is clear that the majority of Covid-attributed deaths are not from Covid-19 directly but due to the numerous systemic failures that exist in our healthcare system.

The RCTs (see definition here) we are waiting for are not going to resolve these problems in the short term, and definitely not before our next handful of surges unless the vaccine is ubiquitously available.

Until then, what do we do?

It is in this context that it bewilders the mind why a drug like ivermectin should not be used for the management of Covid-19 patients for the benefit of its many phases of proven efficacy:

- Prophylaxis using the I-Mask Protocol (shared here) to limit frontline staff infections – this can be extended to all frontline workers, including food industry staff, police, teachers, public transport drivers and hospitality industry workers. That way we can have a reasonable continuation of essential services.

- It can be used to reduce or limit the need for hospital admissions and for early outpatient treatment protocols like this one. We are already overburdened, and ivermectin holds clear evidence of benefit for out-of-hospital treatment;

- It can be used to reduce hospital stay in very sick patients and improve mortality overall using protocols like the MATH+ Protocol – which gives the opportunity to discharge patients earlier and for clinicians to focus on the more severe cases with less therapeutic response.

We are far from a universal vaccine in South Africa. There are many uncertainties, even with the rollout, considering our numerous unique challenges of storage, distribution and uptake.

Patients are dying in droves in the meantime as a result of a system that has been failing them before this pandemic and is being laid bare now.

We have been here before with the HIV pandemic. Weekends in the townships were marred by queues of hearses as young people were being buried in droves. The problem here is not denialism, thankfully, but the consequences of delay are the same. This makes the current situation seem like déjà vu for some of us who were interns more than 20 years ago. The private sector and civil society, through NGOs, intervened independently and turned the tide. Why are we repeating the same mistake now?

If ivermectin was 50% effective (compared with the published 83% improvement in survival rates reported in the meta-analysis by Dr Andrew Hill) it would have saved just more than 4,000 patients since December 21 2020. With a 75% reduction in mortality, we would have saved more than 6,000 lives (300 per day).

In conclusion, the question then remains, what will it take for South Africa to give this cheap and effective drug a chance, and most importantly, what will it take to give the patients a fair shot and chance at survival?

What would our justification be if ivermectin is eventually proven to be effective when the evidence has been around all along? Will the excuse for waiting for large multicentre RCTs be justifiable to the thousands of families who have lost their loved ones?

It is obviously not a cost issue, it is also not a safety issue – it is only an academic evidence issue in Covid-19 specifically that is delaying a potential saving of frontline workers’ and patients’ lives. DM/MC

Dr Nathi Mdladla is associate professor and chief of ICU at Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital and Sefako Makgatho University; deputy president of the Cardiac Anaesthesia Society of Southern Africa; and a reviewer for the Southern African Journal of Critical Care.

Read this analysis piece by Maverick Citizen Editor Mark Heywood here:

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-01-15-using-ivermectin-for-covid-19-what-to-do-when-caution-and-crisis-clash/

Further reading: American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene: Ivermectin and Covid-19: Keeping Rigor in Times of Urgency.

(Photo: geneonline.news / Wikipedia)

(Photo: geneonline.news / Wikipedia)