As I write this, it seems impossible to believe it was nearly 60 years ago, on 22 November 1963, that Americans received a national punch in the solar plexus that was a hinge moment for the national narrative. On that day, President John Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas by a politically agitated but thoroughly disturbed gunman.

The president had been on a pre-re-election campaign trip to Texas, a trip that was designed to heal the growing rifts in the Texas Democratic Party between its liberal and conservative wings. Back in the early 1960s, Texas was still a staunchly Democratic state. Its mostly white electorate remained wedded to the values of the “Solid South” — and the surge of black citizens who would become voters in response to the civil rights revolution was still a few years into the future.

width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen">

The suddenly sworn-in president, Lyndon Johnson, was also from Texas. He had originally come from the hard-scrabble part of the state, but before becoming vice president he had already had decades of service as a congressman, senator, and Senate majority leader.

Coming into adulthood during the Great Depression of the 1930s and having undergone a thorough change of heart over racial attitudes since becoming vice president in 1961, some of his key presidential efforts became the successful pushes for the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the various component elements of the “War on Poverty”. (Had it not been for his dogged pursuit of a disastrous Vietnam conflict, largely at the behest of hawkish, Cold Warrior advisers, Johnson’s place in history might well have been a very different one.)

By 1968, however, those civil rights legislative accomplishments had pushed a majority of white Southerners over to the Republicans in what became known as presidential candidate Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy,” making those Southern states a bastion of Republican support for decades. This historic shift helped provide a vital impetus for the growth of what is now the hyper-partisanship of US society.

Meanwhile, from the 1950s onward, conspiracy theorising radicalism had been gaining ground, drawing nourishment from the hard right fantasies of the John Birch Society and Robert Welch and claims that the civil rights struggle had been a sub rosa part of some alien, communist plot to destroy the nation. In milder forms, adherents to such right-wing views became an important source of ideas for the right-wing takeover of the Republican Party in 1964, with the nomination of Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater for president, although he was thoroughly trounced by Johnson. But the political right, populism and conspiracy theories were growing together into a nearly-permanent bond.

In the untidy present of the ultra-divisive political world of contemporary America, it has now become a commonplace to pin much of the harsh divisiveness of contemporary US society on the ultra-partisanship of Donald Trump, the rise of populism, the racial and economic anxieties of a country moving ever-further towards a majority-minority population and the great economic shifts of jobs and manufacturing away from the traditional heavy industrial areas of the nation. Adding special heat to those factors has been the rise of social media and increasingly virulent, online partisanship, leading many to say that the toxic mix has become both complete and uniquely of this time and place.

But it is also possible to situate this conspiratorial-style, hyper-partisanship in a much deeper historical vein that is not directly tied to that roster of factors just above. Back in the 1960s, written in response to the visible rise of the conspiratorial right at that time, Richard Hofstadter’s classic 1964 article in Harper’s Magazine, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”, delinked this behaviour and way of thinking from any one, unique set of societal or economic factors; instead finding historical tendrils that reached well back into the early 1800s and early anti-immigrant/nativist movements. (Of course, with this newest iteration, the Trumpian version, it has brought these feelings together with a politician whose unique ability to focus all energy on to himself has made this a particularly virulent, dangerous development.)

Hofstadter had written:

“It had been around a long time before the Radical Right discovered it – and its targets have ranged from ‘the international bankers’ to Masons, Jesuits, and munitions makers.

“American politics has often been an arena for angry minds. In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Goldwater movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority. But behind this I believe there is a style of mind that is far from new and that is not necessarily right-wing. I call it the paranoid style simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind. In using the expression ‘paranoid style’ I am not speaking in a clinical sense, but borrowing a clinical term for other purposes. I have neither the competence nor the desire to classify any figures of the past or present as certifiable lunatics. In fact, the idea of the paranoid style as a force in politics would have little contemporary relevance or historical value if it were applied only to men with profoundly disturbed minds. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant.”

After noting that such developments are obviously not a uniquely American phenomenon, Hofstadter concludes his essay, writing:

“This glimpse across a long span of time emboldens me to make the conjecture – it is no more than that – that a mentality disposed to see the world in this way may be a persistent psychic phenomenon, more or less constantly affecting a modest minority of the population. But certain religious traditions, certain social structures and national inheritances, certain historical catastrophes or frustrations may be conducive to the release of such psychic energies, and to situations in which they can more readily be built into mass movements or political parties. In American experience ethnic and religious conflict have plainly been a major focus for militant and suspicious minds of this sort, but class conflicts also can mobilize such energies. Perhaps the central situation conducive to the diffusion of the paranoid tendency is a confrontation of opposed interests which are (or are felt to be) totally irreconcilable, and thus by nature not susceptible to the normal political processes of bargain and compromise. The situation becomes worse when the representatives of a particular social interest – perhaps because of the very unrealistic and unrealizable nature of its demands – are shut out of the political process. Having no access to political bargaining or the making of decisions, they find their original conception that the world of power is sinister and malicious fully confirmed. They see only the consequences of power – and this through distorting lenses – and have no chance to observe its actual machinery. A distinguished historian has said that one of the most valuable things about history is that it teaches us how things do not happen. It is precisely this kind of awareness that the paranoid fails to develop. He has a special resistance of his own, of course, to developing such awareness, but circumstances often deprive him of exposure to events that might enlighten him – and in any case he resists enlightenment.

“We are all sufferers from history, but the paranoid is a double sufferer, since he is afflicted not only by the real world, with the rest of us, but by his fantasies as well.”

Now how prescient can someone be to help us understand our current circumstances more than half a century later?

Using Hofstadter’s insight, the psychological dimension of Trumpism comes into much clearer focus, up to and including the power of that bizarre grab-bag of ideas such as the inchoate QAnon mishmash. If Hofstadter is right, extrapolating to the present, the phenomenon of Trumpism – with or without Trump – is part of a long-standing strand in US life, albeit one now amplified by contemporary electronic communications.

If so, the incumbent president’s refusal to accept his loss in the recent election, and, instead, to wage a persistent (albeit totally unsuccessful) campaign to upend the results via his public rhetoric or the vaudevillian efforts of lawyers like Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell; and to stonewall any assistance towards the president-elect’s transition team have been efforts to substitute a fraudulent reality for the real McCoy the rest of us live in.

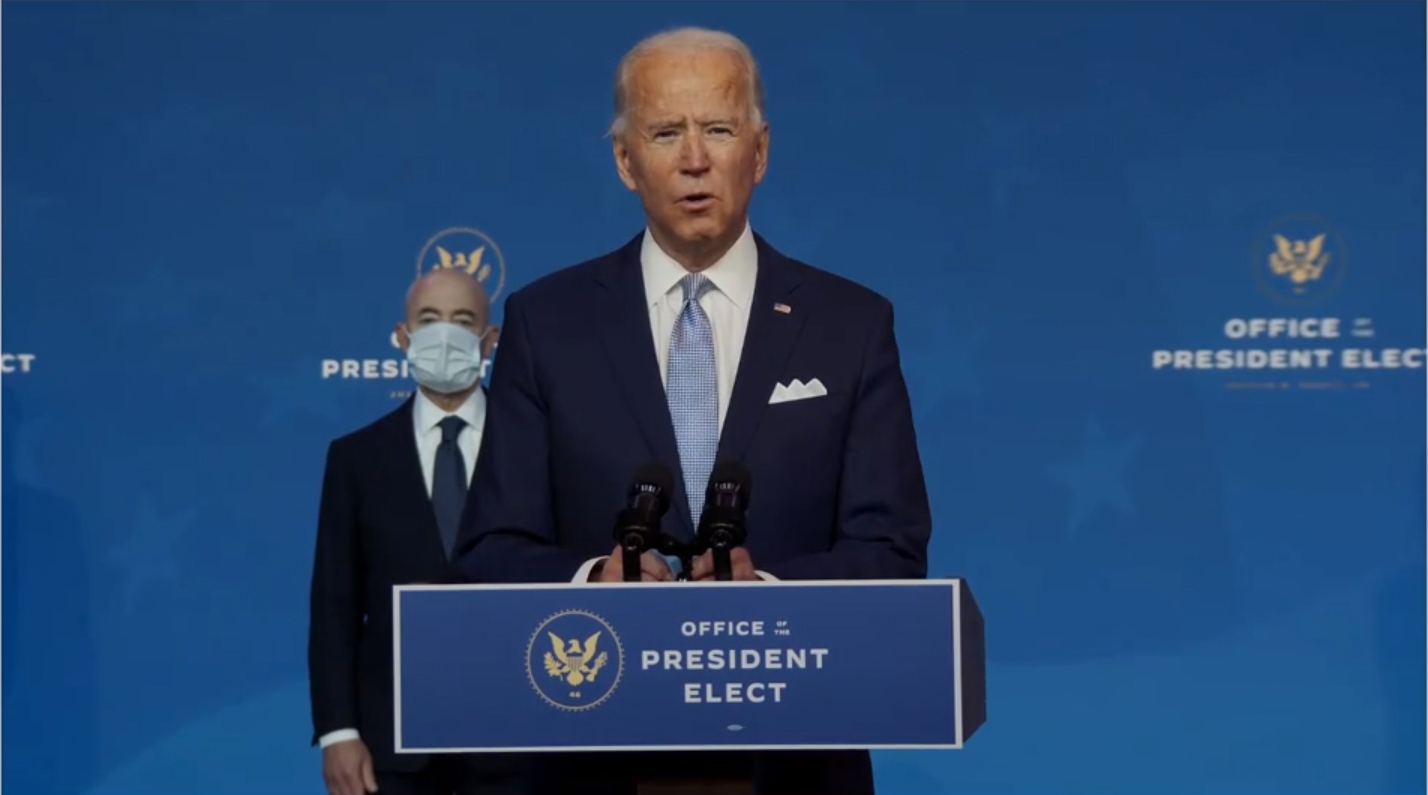

A frame grab from a handout video released by the Office of the President Elect shows US President-Elect Joseph R. Biden speaking during a press conference in Wilmington, Delaware, USA, 24 November 2020. US President-Elect Joseph R. Biden announced his cabinet picks for Foreign Policy and National Security posts. EPA-EFE/OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT ELECT / HANDOUT HANDOUT EDITORIAL USE ONLY/NO SALES

A frame grab from a handout video released by the Office of the President Elect shows US President-Elect Joseph R. Biden speaking during a press conference in Wilmington, Delaware, USA, 24 November 2020. US President-Elect Joseph R. Biden announced his cabinet picks for Foreign Policy and National Security posts. EPA-EFE/OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT ELECT / HANDOUT HANDOUT EDITORIAL USE ONLY/NO SALES /file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/h_56518251.jpg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/h_56518493.jpg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/h_56517669.jpg)