DM168

Act Now! South Africa needs capable public servants

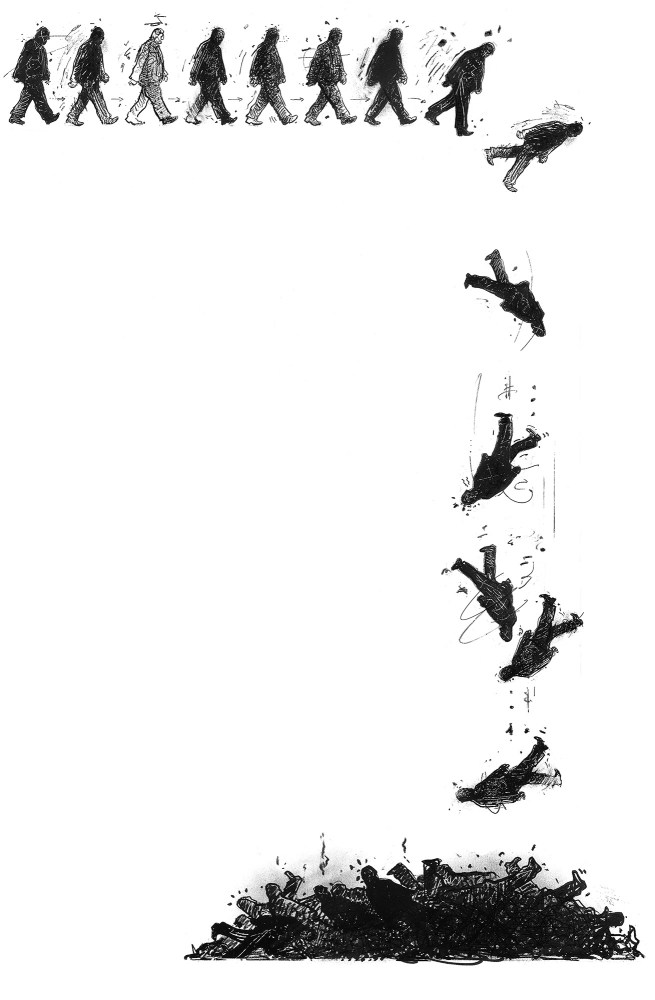

South Africa’s public service is blighted by finely calculated trade-offs that hamper and stall not only policy-making, but crucial implementation.

First published in Daily Maverick 168.

Talk of a capable state and public administration has been front and centre in policy documents such as the 2012 National Development Plan (NDP), and in various administrations. But it has remained largely that – talk. A crucial factor that is largely missing is a public service that is professional, efficient and focused on providing quality services for all South Africa’s people. Consistently. Everywhere. Every time.

In NDP-speak that’s “Outcome 12 – An effective, efficient and development-orientated public service”. Or, as in Chapter 10 of the Constitution, a public administration governed by democratic values, including “a high standard of professional ethics”, transparency, services provided “impartially, fairly, equally and without bias”, public participation and the “efficient, economic and effective use of resources”. These values apply to all spheres of state, all organs of state and public entities, effectively state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Because municipalities have their own corps of employees, South Africa’s public service is the 1.3-million employees at national and provincial level regulated by the Public Service Act.

The public service remains a complex and often noxious mix of political interests, protocol obsession, personal ambition and the brutality of managerial high-handedness that leaves those seeking government services having to do so in often putrid conditions.

That is not to say there are not exceptions. Ordinary public servants in offices countrywide do their jobs unswervingly, often against the odds. Whistle-blowers, from a provincial Master’s Office to SOEs, have called out wrongdoing.

And the tributes to the late Auditor-General Kimi Makwetu at his memorial service on Tuesday highlighted a consistent and lived integrity, ethics, diligence and commitment to South Africa’s constitutional values.

Yet even as head of a constitutionally established institution to support democracy, Makwetu was threatened – as were his audit teams – over their audit reports documenting (mis)management and malfeasance.

The Auditor-General became increasingly vocal expressing disappointment about the culture of no consequences and impunity as accounting offices and political leaders failed to act.

“The law does not require a person just to sign a document. It requires the person to scrutinise the document… and to ask questions,” Makwetu said in November last year at the release of the national and provincial consolidated audits.

Too little of this happens too seldom across the public service. And government has long known this.

Between September 2013 and 2015 when it was dropped after Jeff Radebe became minister in the Presidency, the Management Performance Assessment Tool (MPAT) showed the government’s own contraventions of regulations and laws, procurement violations and inadequate service delivery. While the 2015 final review MPAT document identified “pockets of excellence”, it also highlighted weak leadership that “contributes to administrative failures in government”.

The capable state and the public service got an NDP chapter for itself – Chapter 13, a section of which states: “The requirement for Cabinet to approve the appointment of heads of departments makes it unclear whether they are accountable to their minister, to Cabinet or to the ruling party.”

Arguing for a service that is “sufficiently autonomous to be insulated from political patronage”, the NDP doesn’t quite envisage a depoliticised service of career public servants. Instead, it’s all about stabilising that so-called political-administrative interface.

Proposals include an administrative head to be established either as a new position or by allocating this responsibility to the director-general in Public Service and Administration or the Presidency, who also doubles as the Cabinet Secretary.

Central to this ambivalence over a depoliticised career public service seems to be the role of senior servants in policy-making for which the NDP and others assert political accountability to ministers is a must.

This question over policy points to a still-unresolved governance sticking point, and helps explain the inordinate delays in key policy measures, including the spectrum auction to release broadband, renewable energy projects and easing business red tape.

According to the NDP, “the political-administrative interface will necessarily remain contested terrain, and so an important role of the administrative head of the public service would be to mediate issues that arise”.

And, with that, the space is provided in the public service for political influence in administrative appointments, despite the acknowledged tensions and conflicts this creates.

To be clear, a depoliticised public service is not about not allowing public servants to support or belong to a political party. It is about ensuring a clear boundary between the political – driven by Cabinet ministers, supported by advisers and policy wonks – and the administrative, whose most senior official accounts for performance and budget to the minister, the Auditor-General, Parliament and, ultimately, South Africans.

The world over, public service structures are different. In South Africa, the transition to democracy meant sledgehammering together various apartheid and Bantustan administrations and, as ANC lingo puts it, getting control of the levers of state.

Some things were changed immediately, such as the democratising 1994 Public Service Act. Others required transitional arrangements pending the Constitution’s 1996 adoption. By 1998, concerns had emerged, sparking initiatives such as the national public sector anti-corruption conference organised by the Public Service Commission.

That political-administrative interface the NDP talks of already then proved tricky. Not only for instability, but being – not infrequently – enmeshed with political interests given the governing ANC’s internal battles and deployment policy.

“Election to an ANC leadership position is viewed by some as a stepping stone to positions of power and material reward within government,” said outgoing ANC secretary-general Cyril Ramaphosa’s organisational report at the 1997 Mahikeng ANC national conference.

Almost a decade later, political fall out hit South Africa’s public service amid the factional run-up to the 2007 Polokwane ANC national conference that elected Jacob Zuma party president, and continuing tensions that ultimately led to the ANC’s September 2008 recall of President Thabo Mbeki.

Senior public servants kicked for touch for months on many policy decisions. Reluctance had set in, in case a decision backfired in the factional battles of the ANC, whose deployment committee had a significant say in their public service post, or once a new minister was appointed.

By May 2010, Cabinet had to deal with the tensions and instability within the top public service ranks. It extended directors-general contracts to five years, and clarified the composition of selection panels to include different ministers as part of the process from open job advert to Cabinet appointment.

Public Works went through three directors-general from April 2009 into early 2011 as the Nkandla saga erupted.

One of them, Sam Vukela, challenged his dismissal and returned to the post, where he became mired in corruption claims over state funerals for struggle stalwarts Billy Modise, Zola Skweyiya and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

Themba Maseko, CEO of Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) and Cabinet spokesperson, fell out of favour for refusing Gupta media access to the government’s advertising budget.

In early March 2020, Vukela denied all at a meeting of Parliament’s Standing Committee on Public Accounts (Scopa), just after Public Works and Infrastructure Minister Patricia de Lille outlined steps she was taking to get the presidential go-ahead to suspend the DG.

That go-ahead was needed because in October 2017 then Home Affairs DG Mkuseli Apleni argued against suspension, saying only the president could do so, not the minister. He was back in office until July 2018, when he resigned to join the private sector.

It took two years after the bruising 2010 falling-out between then communications minister Siphiwe Nyanda and DG Mamodupi Mohlala-Mulaudzi for a settlement to be brokered. More discreet were the two DGs and three acting directors-general Ebrahim Patel saw out while heading Economic Development from 2009.

In this set-up, veteran public servants have been sidelined and effectively pushed out in the flux of politicking and political interests.

Public works DG Mziwonke Dlabantu left in 2017 after Nkosinathi Nhleko became minister following his stint as minister of police, where he oversaw the appointment of Hawks boss Mthandazo Ntelmeza, despite a judge describing the policeman as dishonest and lacking integrity. Nhleko is on public record as saying the judge had expressed an opinion, not a finding.

Themba Maseko, CEO of Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) and Cabinet spokesperson, fell out of favour for refusing Gupta media access to the government’s advertising budget.

In early 2011, Maseko was moved to Public Service and Administration, but resigned that July.

“[T]he relationship did not gel – things did not work well. I attribute this to the fact that he [Minister Richard Baloyi] had felt I was imposed on him as a DG,” Maseko told the Zondo Commission in early November 2019.

Directors-general continue to be appointed by Cabinet. Decisions on DGs are kicked to the president, who must delegate to the minister the power to act. In De Lille’s case, this was withdrawn after she suspended Vukela in July 2020, and switched to Minister in the Presidency Jackson Mthembu.

That may be another signifier towards a super presidency as the centre of government power.

In 2018, then public service and administration minister Ayanda Dlodlo had looked into institutionalising direct support to the president to manage government in the Presidency, together with specific units to deliver on government priorities. Some of that seems to have been realised with the establishment of the Investment and Infrastructure Office and the Project Management Office in the Presidency.

The 2014 Public Administration Management Act bans public servants from doing business with the state — it’s a criminal offence punishable by up to five years’ jail under Section 8. The 2016 Public Service regulations echo this.

Meanwhile, it’s been mostly quiet on the political-administrative interface stabilisation front the NDP talked of.

Public Service and Administration says it is supporting the Presidency on NDP proposals such as “a national administration to support the Public Administration Management Act” and related legislative amendments, according to Wednesday’s briefing to MPs.

But the White Paper, or government’s policy stance, on transforming and modernising the public administration didn’t make it to the ministry on time. The exact impact of this is unclear.

In all this, questions arise over the Public Service Commission. Established in the Constitution to propose measures for an effective, efficient public service, the hiring, firing, promotion and transfers, the NDP wanted it strengthened. But while the commission members are appointed through a parliamentary process, underscoring its independence and significance, its budget is allocated by Public Service and Administration. On Thursday it emerged Cabinet decided the National School of Governance would lead the professionalisation of the public service in the proposed draft public service framework, including recruitment, induction, performance management and professional development. That leaves the commission in a curious place.

The 2014 Public Administration Management Act bans public servants from doing business with the state — it’s a criminal offence punishable by up to five years’ jail under Section 8. The 2016 Public Service regulations echo this.

In September this year, MPs were told that the number of public servants — unlawfully — doing business with the state had increased from 1,068 to 1,539 between February 2019 and April 2020. Most are from provincial administrations.

Efforts since 2017 to get ministers, DGs and their provincial counterparts to act on such transgressions seem not even to have solicited that many “Your letter is acknowledged…” responses. And not once yet has the statutorily required annual financial disclosure from senior public service manager hit 100%.

If this is the example set by political leaders and administrative seniors, the culture of impunity cannot surprise. Such attitudes at the top set the tone lower down.

Bending to “instructions from above” emerged as the reason for shortcuts in Project Marathon, the transfer to unregistered NGO carers that caused the deaths of 144 Life Esidimeni mental health patients.

During the 2017 arbitration hearings, ex-Gauteng health MEC Qedani Mahlangu and health boss Barney Selebano invoked without proof the AG’s concerns over evergreen contracts. But inquiry chairperson, former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke, found: “Both Ms Mahlangu and Dr Selebano called the name of the Auditor-General in vain”.

South Africa’s public service is a complex and often toxic mix of interests and influence. Frequently, finely calculated trade-offs in this context have stalled not only policymaking, but also crucial implementation.

Following instructions from above without question and sticking to well-worn, even if ineffective, ways has embedded an institutional culture that grinds down newcomers who may want to do things differently. The obsession with protocol and hierarchies is dumbfounding.

None of this is to say there are no exceptions. There are, plenty, particularly in those public service places that underscore transparency, accountability, integrity and ethics – even when no one’s looking. But the critical mass is needed now. South Africa is in increasingly dire socioeconomic circumstances that are deepening poverty and inequality.

The capable state and professional, efficient public service requires more than pretty words and logos, or even legislation. It requires political will to act. DM168

You can get your copy of DM168 at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Yip. But not much will for anything much in SA government

The National Govt, the Provincial Govts, the Public Service, the Municipal Govts and SOEs, with few exceptions, are mired in the same bog. By and large they are ANC deployees, mostly incompetent, many corrupt, but worst of all ignorant and arrogant to boot. Never mind being overstaffed and overpaid, they simply can’t pass muster.

I really don’t see a way out of this, at least not in the short to medium term and by then it’ll bee too late.

This is a hugely difficult topic, which cannot be summed up in one article or with one comment.

Some observations:

There is a lot that still works (e.g. at some municipalities). This is not necessarily “because of” good (political) leadership, this is mostly “in spite of”. There is still a core of silent, hard working officials who simply knuckle down and get the job done – mostly in the face of public abuse, and in disregard of attempts at interference.

Watch the “suspension” space. Yes, many of the suspensions of officials are necessary where there was corruption and poor performance. But many suspensions are simply the way in which politicians gets rid of officials who do not do their bidding unquestionably. The second edge of the same blade is the “restructuring” trick. If you can’t fire an official standing in your way, you “restructure” the position. Remember, if an official takes a municipality to labour court, the official carries their own legal costs; the municipality pays their lawyers from tax money. The system is unfair and almost unbeatable.

At the heart of a lot of incompetence and corruption was the ANC policy of Cadre Deployment. This was recognised internally by some in the ANC, and someone like minister Gordhan has long ago indicated that this practice should stop (i.e. competence should be the appointment criteria). Yet, all parties still (mostly) appoint their “own” into positions of leadership.

So, I agree with the rationale of this article, the country needs a new, professional administration. The irony is that at policy level, both the ANC and DA agrees. However at implementation level, the power-players still do what they like.