What's cooking

Plant-based living is gaining popularity – which is good news for our battered planet

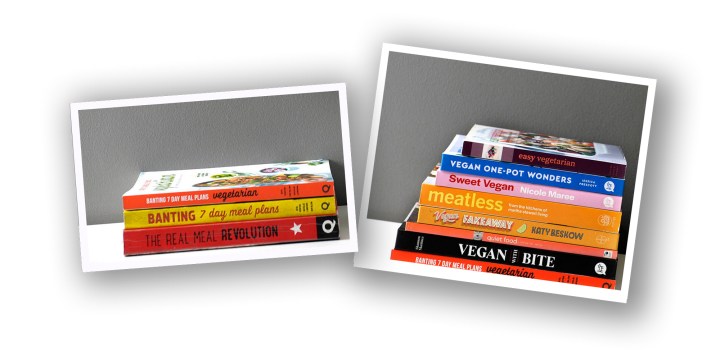

Between 2018 and 2019, the sale of vegan cookbooks in South Africa more than doubled, while global demand for meat hasn’t changed much. We look into an international food trend against the backdrop of South Africa’s food cultures and concerns.

Food has always been political and one of its most visible aspects today is the social-media-driven focus on veganism.

Endless streams of gleaming-bodied young people offer their recipes and how-to’s on Instagram and YouTube and, while, these might be discounted by some as early-21st century navel-gazing posing as climate-change activism, it is harder to dismiss veganism as flash-in-the-pan trend when the publishing industry — which calculates its bottom-line carefully — responds with such alacrity.

Linda Buthelezi, publicist at Jonathan Ball Publishers, a South African publisher whose list of titles to be released in the final quarter of this year contains five vegan cookbooks, said sales of vegan cookbooks had increased by 56% from 2018 to 2019.

“We are anticipating greater growth for this year, but we can’t conclusively confirm this yet as the year isn’t done,” she said.

Since book production takes a lot more time than posting a photo of your Buddha bowl does, and because it results in a product people need to spend their money on, figures like this point towards the fact that consciousness around food consumption among the middle-classes is growing.

This reading of the publishing trend seems to be borne out by a Euromonitor International report from November 2019 called “Strategic Themes in Food and Nutrition”, which shows that while less than 5% of South Africa’s population is vegetarian, around 20% of the population is at least trying to limit their meat intake.

The report calls this “a growth of meat reduction, not a growth of meat avoidance”.

Jessica Smith, a bookseller at The Book Lounge, an independent bookshop in Cape Town, says: “There is definitely a growing demand for books about veganism and vegetarianism, and this ranges from cookbooks to more critical theory.”

Veganism and vegetarianism are not the same thing.

Vegetarianism shuns the consumption of meat. Veganism shuns the consumption of any animal products, as well as the concept of animals being used as part of the agricultural industrial complex. Vegans will consume no animal products. Not only do they not eat any meat, they eat no eggs, no butter and no honey. Serious vegans will check every product for animal ingredients or animal testing, and they will not wear products made of wool or leather.

Meat-eating versus plant-eating provides a rich source of online fisticuffs, but so do the various lines crossed by aspirant vegans who are energetically policed by hardcore herbivores demanding an all-or-nothing approach to the vegan lifestyle.

For this reason, a term that is used more freely, because it is less contentious, is “plant-based eating”. Cookbooks coming to market now are mostly aimed at the plant-based eating market.

“A big part of the vegan boom in publishing has to do with being cool and trendy,” says Smith. The trend means that bookshops are now unable to keep all the books on plant-based eating in stock.

“Which is wonderful. We’re able to be more selective and curate our collection in a way that works for us and our customers.”

She said that even well-known international chefs, like Yotam Ottelenghi and Jamie Oliver were bringing out cookbooks that contain more plant-based recipes.

“This may just be in an effort to remain relevant with a new audience, but it feels as though it comes with a deeper awareness, and also encourages readers to move away from the idea of meat being the central focus of a dish.”

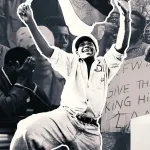

South Africa has a long and strong culture of meat-eating, so much so that Heritage Day in September is known as “braai day”, based on a call by Jan Scannell — better known as Jan Braai, the author of cookbooks for braai-fire enthusiasts — for South Africans to come together around fires to prepare “great feasts”. This, the Jan Braai website proclaims, is a noble cause “which will contribute to strengthening South Africa as a nation through this act of nation building and social cohesion”.

In a country that is divided not only between those who “shisa nyama” (eat meat) and those who “braai”, but between those who are in a position to regularly buy expensive organic meat and produce, and those who cook thin stews from rotten vegetable off-cuts given to them by generous street-vendors at the end of the day, veganism is a particularly loaded debate.

Meat and meat products are too expensive to regularly include in many South African families’ daily diets, but considering how many resources are depleted in the process of bringing meat to the table, many argue that what matters is not so much how much a bag of chicken pieces costs, but whether, in the face of an apocalyptic climate crisis, the planet can afford another bag of chicken pieces.

The vanguard of this questioning is mostly being led by young activists around the world. What we eat will always be political because it is grown in the earth of a hotly contested planet, but also because how people eat differs according to class, race, fortunes, traditions, geography and economic status. One of the qualifying aspects of plant-based diet curiosity — if not commitment — is that it seems to be indicative of intergenerational conflict.

Smith says: “It feels as though there is a greater move towards taking the theory of a more sustainable and conscious way of living and putting that into practise. Aside from vegan and vegetarian cookbooks, books that have also started to sell more are those that tend to follow environmental themes, so things like zero-waste living, practical self-sufficiency, and books that list ways to make personal everyday differences. Now more than ever, these themes form part of early learning at schools and so from a young age, children grow up with an environmental consciousness and awareness.”

The people who tend to roll their eyes at veganism are often dismissed with an “OK, Boomer”, a put-down that focuses on the age and rigidity of people who defend their right to eat flesh. Educated younger people don’t necessarily all aspire to veganism, but they’re less likely to roll their eyes at the idea of a way of life consciously constructed around the vision of an uncertain environmental future.

The increased sale of vegan and vegetarian cookbooks, however, doesn’t mean people are buying less meat.

Wandile Sihlobo, chief economist at the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa and author of the book Finding Common Ground, says: “The discussion about the move away from animal meat to plant-based products is only starting to gain momentum in the agricultural economics research space recently, but still not at a large scale. For a long time, research and commentary have largely been around labelling – whether plant-based products should be called meat, milk, etc. – not necessarily about bigger questions about the potential shift in demand. Part of the reason is that, in volume perspective, there haven’t been any noticeable shifts in global demand for meat.”

In an article about international meat and dairy production, researchers point out that the world now produces more than four times the quantity of meat it did 50 years ago, and that 80-billion animals are slaughtered for meat each year. The world produces around 800-million tons of milk each year now, also double what it did 50 years ago.

Livestock production has well-documented and profound environmental impacts on greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption and land use. But this argument often falls on deaf ears when it comes to convincing South Africans who can afford meat to eat less of it.

Anesu Mbizvo, co-owner with Banesa Tseki of The Nest yoga studio and vegan café in Greenside, Johannesburg, said in an interview with Voice of America: “In African culture, a big part of a family’s net worth is in their livestock. Their livestock define the wealth of a family. And so, when you slaughter an animal at a gathering, it’s seen as you giving of yourself. Whereas getting some vegetables from your veggie patch doesn’t really equate to the same amount of giving.”

Deirdre Hewitson has been a vegan — though she prefers “plant-based” because she says she wouldn’t refuse a slice of cake made with egg at a friend’s house because of the love with which it is offered — for many decades, far longer than even the oldest salad platter on Instagram.

“I remember once walking along the sea and some guys had caught a fish, which was flapping and fighting for its life on the rocks. I was so close, I could see its eyes bulging as it gasped for breath and I thought, ‘fuck, it’s dying’. I was only about thirteen. The image never left me.” She became vegetarian and later, when she was pregnant with her first child and started to wonder about the kind of planet she’d be leaving for her children, she became vegan.

“I come from an Afrikaans family. Meat is part of the culture. I never made a fuss about veganism, but people always make it their business. Even at social occasions, someone I don’t know would notice there was no meat on my plate and then they’d start an argument with me about my choice not to eat meat. Once someone tried to sneak bacon into my food and I remember one year we travelled to Namibia and for the whole time we were away, I had to eat chips for supper every night because there just weren’t any other options. When my children came along, I was sometimes accused of child abuse. It’s hard work being a vegan. You’re often under attack, either from more committed vegans or from defensive meat-eaters.”

She says she is glad that her “weirdo” lifestyle has become more mainstream. It means there’s a growing awareness of what capitalist consumption patterns mean for the world and the future.

“And on a personal level, because I have more choices.”

What has the increased sale of vegan cookbooks meant for The Real Meal Revolution, the 2013 book by Tim Noakes that, at last count in 2018, had sold a quarter of a million books, a South African record for book sales?

The famous red cookbook had almost seismic effects on the way in which South Africans thought about how they ate. It propounds the idea of eating a low-carb diet that focuses on animal fat and animal protein, not only for weight loss, but for various health issues too. The diet is mostly known in South Africa as “banting” (it’s called “keto” or LCHF for low-carb, high-fat in other countries).

The book’s publisher, Libby Doyle, at Quivertree, says, “The Real Meal Revolution is still selling around 100 copies a month.”

In spite of the book’s popularity — or maybe because of it — Noakes and his co-authors were severely criticised on many fronts, one of which was that their cookbook was written for an elite group of people who could afford grass-fed beef, snack on expensive charcuterie and eat as many eggs as they could stomach. Most South Africans, the argument went, were not in that class. Were the benefits of this diet meant only for the rich?

Rita Venter, who is unconnected to Noakes, wrote a follow-up book published last year, called Banting 7 Day Meal Plans, which Noakes endorsed with a foreword. She did this on the strength of the eponymous Facebook group she started in 2014 and which now has a following of more than 2.3 million members, of whom 1.3 million are South African and the rest are mainly from other African countries. The new South African banting book contains recipes reflecting a far more economically realistic picture of how we eat: cabbage, kaiings, tripe, and chicken feet, hearts and livers.

And though Banting 7 Day Meal Plans has sold just over 1100 copies per month in the year since it was published, it still hasn’t ticked all the boxes.

Venter says: “We have huge numbers of members who do not eat meat for religious reasons, or any animal products for moral or health reasons, and we wanted to offer them something too.”

The result is the new Banting 7 Day Meal Plans Vegetarian, of which just under half the recipes are suitable for vegans.

If “vegan banting” sounds like the ultimate oxymoron, it also sums up the food political moment of the South African middle classes. We seem to be in a state of flux, either actively moving towards a more plant-based diet for health and environmental reasons, or thinking about going that way, while nostalgically grappling with our meaty history.

Anthropology postgraduate student Siv Greyson sums it up: “My own feelings about veganism are all over the place. I think mainly I advocate for people to be able to feed themselves as best as they can. Since I start from a point of anti-capitalism, I push more for people to have land so that they can grow their own veggies and fruit and have their own animals. That’s my vibe at the moment. I also stopped being a vegetarian so that’s been quite the journey.”

A middle-road winds through the voices that pull one way or the other between the meat versus plant-based debate, summed up by the useful word “flexitarian” that was recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary for the first time in 2014. “Flexitarian” relates to someone who primarily, but not strictly, keeps a vegetarian diet. Ironically, the word “Anthropocene” was taken up in its hallowed pages in the same year. The word has been adopted to refer to “the era of geological time during which human activity is considered to be the dominant influence on the environment, climate, and ecology of the Earth”.

Which is precisely why people are advocating away from animal products, which cost the Earth so dearly, towards a friendlier way of nourishing ourselves, and a more equitable way of providing food for all the Earth’s people.

One flexitarian, who did not want to be named, put it like this: “Veganism is such a flashpoint and I think right now, except for the dedicated and angry meat eaters and the dedicated and angry vegans, the rest of us just muddle along trying to do our best, glad that we have the luxury of options, when so many other South Africans are begging for a loaf of bread and some peanut butter outside shops since lockdown.” DM/ ML

We HAVE to put this myth (that going vegan, will save the planet) to death. The world’s most sustainable farmers (like Gabe Brown in North America, Christine Jones in Australia and 1000s of others) have learned that the health of their soil is greatly enhanced by incorporating LIVESTOCK into their farming systems. Plants and Soils both evolved with animals, and they need them to reach their full potential. Grass-fed beef, pork, lamb, goat and poultry are all ESSENTIAL for a healthy environment. It is factory farmed/feedlot meat that we have to BAN. With that single change, meat WILL become slightly more expensive, but a great deal more nutritious, and feeding 10 billion people will be a walk in the park. Bruce Danckwerts, CHOMA, Zambia.

Dear Bruce. In India where I was born in a little, mainly farming village, most families kept animals (cows and or goats) for milk and looked well after them ! Their dung was used to plaster the ‘homes’ they lived in (until the switch to cement came about) as well as ground fertiliser in their farming lots. BUT… they never slaughtered them for meat. Those that were not vegetarian, consumed fish or chicken as a part of their diet. Just something for you to ruminate on please. Give up the pedanticism … it doesn’t suit you or improve your argument.