It is a frequently held perception by harsher critics of the American political world to say dismissively it doesn’t matter very much who gets elected. For some, it is the argument that all politicians are pretty much the same. Yes, opposing cohorts replace one another, but nothing really changes. This is the insight from early 20th-century Italian social scientist Vilfredo Pareto, who labelled this process “the circulation of elites”.

Others argue that there is a hidden class that really runs everything or, alternatively, perhaps, they are in thrall to some deeper, more hidden realities. For some, it is inevitably international bankers and/or global capitalists. For others, it may be an elusive conspiracy such as the one presumably revealed via QAnon. Or, perhaps, it is some kind of “deep state” collective that runs everything from secret headquarters somewhere, absolutely everything.

One guiding principle of such theories is that politicians in the public eye are just puppets dancing to the tunes of whoever really is in charge. And, under some arguments, those in charge are actually just bending to those implacable wheels of an economic substratum. By such theories, the class interests of the real masters are what matter above all, and everything else is just clever shadow boxing.

The difficulty in such theories is they don’t provide much sustenance for interpreting real differences in policies that may come about in the wake of changes in national leadership. Most especially, such theories help us very little in understanding how the differences in foreign policy approaches and a nation’s international relations come about. Other factors are at work as well. As with all other nations and their own unique geopolitical circumstances, the long sweep of history, economic relations and resources; the character and temperament of leaders matters as well — and that is just for starters.

And so here our task is to try to work out the differences between the foreign policy goals and strategies between the two candidates for the American presidency. Surely they both must operate in the same world, subject to the same challenges and pressures, even if they are hoping for some very different outcomes (even if Donald Trump is often accused of existing in an alternate universe)?

Then it dawned on this writer there actually was something substantial that was held in common by the two candidates. “Really?”, this author already hears all of you muttering under your collective breath, “What can you possibly mean by that?”

Well, here goes. Let me explain. Whoever is inaugurated as America’s president on 20 January 2021, that person must deal with an America whose international presence, impact, respect, and influence will be at its lowest ebb in nearly a century. The Pew Research Center tracks such trends and it has offered such sad determinations in their reports such as this.

We now live in a world where Chinese leader Xi Jinping seems to be gaining more respect than the US president. This is despite the fact there is growing nervousness about the potential for a Chinese imperial overstretch in the thoughts of a growing number of foreign observers. With the exception of just a handful of nations around the world for rather specific and partisan reasons, the reputation of the US has dropped to historic depths in many others, let alone in a belief in the idea that America represents an exemplar; that it is the shining city upon a hill, a light unto the nations, its exceptionalism — this as one of the core ideas historically in American civic mythology.

Consider the obvious fact that in 1945, at the end of World War 2, the American project had become uniquely unrivalled on the global stage. Its productive industrial base, its financial strength and its military prowess were virtually unchallenged globally. It held the nuclear monopoly, and its GDP exceeded virtually any other likely combination of nations, despite just being a small fraction of the total global population.

Inevitably that would change. As other nations revived, American relative dominance correspondingly decreased. But then, through a combination of multilateral American alliances, the vast economic power of other western and far eastern nations such as Japan and South Korea, and the internal dynamics of the Soviet Union itself, the governments of the old Soviet Union and its Eastern European satrapies collapsed in an untidy heap, and American global pre-eminence was re-established, almost by magic. It was “the end of history” and the triumph of late 20th century American liberal democratic values, globalisation and growing internationalism, that is until 9/11 helped shatter that myth.

The American colossus was in place, but the world also engineered real pushback against the dominant power. The US found itself enmeshed deeply in military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan simultaneously (eventually along with a third smaller one in Syria too), as well as facing a rapidly blooming economic rival in China, a resurgent Russia led by a ruler with scores to settle, as well as other smaller, but very real pushbacks.

By the time Barack Obama entered the White House in 2009, the watchword was not how to expand America’s footprint, but how to refocus American efforts to deal with a different type, size and scale of challenge, much of it coming from its new rival, China. And maybe other more existential ones as well. As a result, global policy would be constrainment, rather than yet further engagement. (See: Obama’s Foreign Policy: How will ‘Constrainment’ work in 2016? right from the early days of Daily Maverick.)

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2013-08-12-obamas-foreign-policy-how-will-constrainment-work-in-2016/

Even that highly touted pivot to Asia was largely based on economic efforts, rather than an expansion of defence and security capabilities. By the time Obama left office in 2017, the conversation about America’s place in the world had become one of making the best possible accommodations in a world that was no longer dominated by the US.

Then, in 2017, as far as incoming president Donald Trump was concerned, he saw his task as, yes, the canard, “Make America great again” (whatever that really meant), but not, crucially, about any sense of dominating the world. As a result, it was “America first!”, not “Fix the world!”

Or, as New York Times editorial board member and veteran foreign correspondent Serge Schmemann reminded us just the other day, “The troubles of the world are not all Mr. Trump’s doing. China’s rise, Russia’s machinations, the tenacity of Mr. Maduro [in Venezuela], the sectarian feuds in the Middle East and the new crop of authoritarian rulers were all underway before he was inaugurated, and would have taxed any president.”

Accordingly, whoever wins this election will be forced to confront the same set of realities and challenges. Or, as Schmemann adds, “What would a Joe Biden victory in November’s election mean for American foreign policy? Many of the dominant currents of world affairs will not change as a result of a change of administration or tone in Washington. Russia will still meddle in foreign elections; China will demand a role commensurate with its wealth and military might; Europe will contribute too little for its defense; a reconfigured Middle East will still be buffeted by sectarian, social and ethnic divisions; North Korea and Iran will pursue their nuclear ambitions.”

Both Joe Biden and Donald Trump will be forced to address this same reality, regardless of any predilections to the contrary. The challenge to understand is how they will choose to accept this reality of lessened influence, power and respect and how they will respond to the global challenges that will be there, regardless. And that, in turn, will affect the very different policies they choose to embrace to deal with America’s diminished reality.

For the Biden camp, it will likely be a need to accept — even embrace — the idea that full-on, flat-out globalisation and internationalisation in economic and trade relations has real trade-offs that can have negative impacts on big swathes of the nation’s economy and workers. Moreover, Biden policies will have something of the texture of a new, improved flavour Obama administration 2.0.

It will include a re-embrace and re-engagement with the country’s alliance structures in Europe and East Asia as the most reliable, and, ultimately, most cost-effective means to counterbalance the ambitions of both Russia and China. Furthermore, a Biden administration will reorder priorities back towards international efforts to deal with climate change, epidemiological disasters and nuclear proliferation.

Concurrently, while a second term for Donald Trump would also have to address this diminished role and impact, his responses to these circumstances would continue the sharp inward turn away from an engagement with the international community. “Make America Great Again” would continue to insist on starkly transactional processes. Again, as Schmemann argued, “But without Mr. Trump’s crude insults, erratic shifts and self-serving views, the United States will have a chance to reclaim at least some of its moral authority, and his coterie of wannabe dictators will feel less comfortable. Mr. Biden has already pledged to rejoin the Paris climate accord, and he is likely to re-enter other international forums and to take steps to repair relations with miffed allies.

“If Mr. Trump is re-elected, he will conclude that he has a mandate to continue in his dysfunctional statesmanship, and the world will have no choice but to conclude that the past four years were not an aberration, but the United States they now have to deal with.”

Without question, rather than just being one more ratchet in the circulation of the elites or the effect of the implacable wheels of economic determinism, this upcoming election really does offer a stark choice of governing styles. But more than just style, the choice offers American voters a way to indicate which direction the country will turn in dealing with the realities of America’s more limited freedom of action, its constrainment of choices and an ability to affect the future of the globe. DM

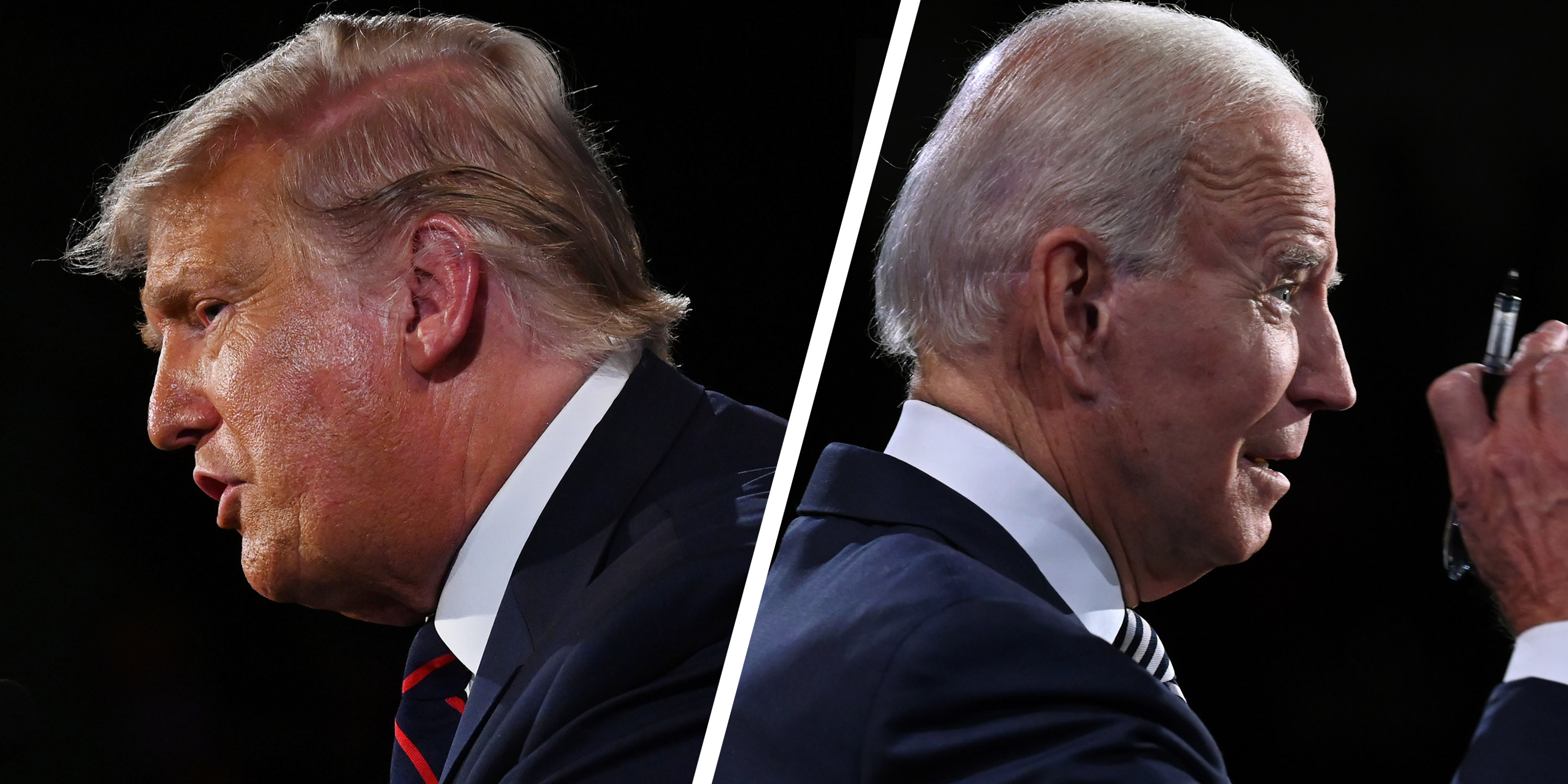

United States President Donald Trump (left) and Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. (Photos: EPA-EFE/OLIVIER DOULIERY / POOL)

United States President Donald Trump (left) and Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. (Photos: EPA-EFE/OLIVIER DOULIERY / POOL)