MUKURUKURU MEDIA

‘Re-imagining mining to improve people’s lives’: How a slogan leaves a bitter taste for Limpopo villagers

Limpopo mining villages resemble ghost towns as migrant workers move out due to mine closures, draining away their economic lifeblood and increasing the devastating impact of Covid-19.

In a different time, when the Bokoni Platinum Mine was in full operation and the lifeblood of the economy in the Atok area of Limpopo, residents like Helen Manala made a good living from renting out units of accommodation to migrant workers employed at the mine.

The villages of Monametse, Atok, Mokgotho and Sefateng accommodated an estimated 35% of the more than 6,000-strong workforce.

An abandoned room in Monametsi village which used to be the temporary home of a mineworker. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

The need for accommodation by people who moved into the area in search of work and other business opportunities gave residents like Manala an opportunity to cash in by building accommodation units.

Life in the area revolved around the platinum mine, which started operating in the 1960s. But when its owners, Anglo American Platinum – which uses the slogan “Re-imagining mining to improve people’s lives” – placed it under care and maintenance in 2017 following a fall-out with its BEE partner, Atlatsa Resources, the community was left to find other ways to survive.

The entrance to the Brakfontein shaft of the Bokoni Platinum Mine, which was a hive of activity with hawkers, taxis and people, but is now deserted. ( Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

On 27 July 2017 Atlatsa Resources, the main shareholder with 51% of Bokoni Platinum Mines, announced a financial restructuring plan for Atlatsa Group, a conditional disposal of mineral rights to Anglo American Platinum and a care and maintenance strategy to Bokoni Platinum Mine.

With a growing number of mines being placed under care and maintenance, unemployment within the region is likely to remain high. It is feared that the Covid-19 lockdown, which has already devastated rural communities, could have an even more dire effect on mine-affected communities like Atok.

The footprint of the mine is everywhere in Atok. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Unfortunately, there is only one certainty when it comes to mining – the commercially extractable resources will run out. And when this happens, it spells disaster for host communities like the Atok villages.

The villages of Monametse and Ga-Mokgotho are situated between two of Bokoni Platinum Mine’s underground shafts, with a road connecting the two shafts to the mine offices passing right through residential areas.

The taxi rank and bus terminus near the Bokoni Platinum Mine were a hive of activity, but is now deserted after the mine was shut down and placed under care and maintenance. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Often people living in this village used to experience noisy, dusty days throughout the year due to the frequent traffic, including haul trucks and heavy mine machinery. The community used to be home to almost 35% of mine employees living in almost 500 rental rooms within the village.

Most of these have since been vandalised, with windows, doors and other valuables stolen. Owners of the rooms are left with only dilapidated structures which, even if the mine were to be reopened, they might not be able to salvage due to the high cost of repairing them.

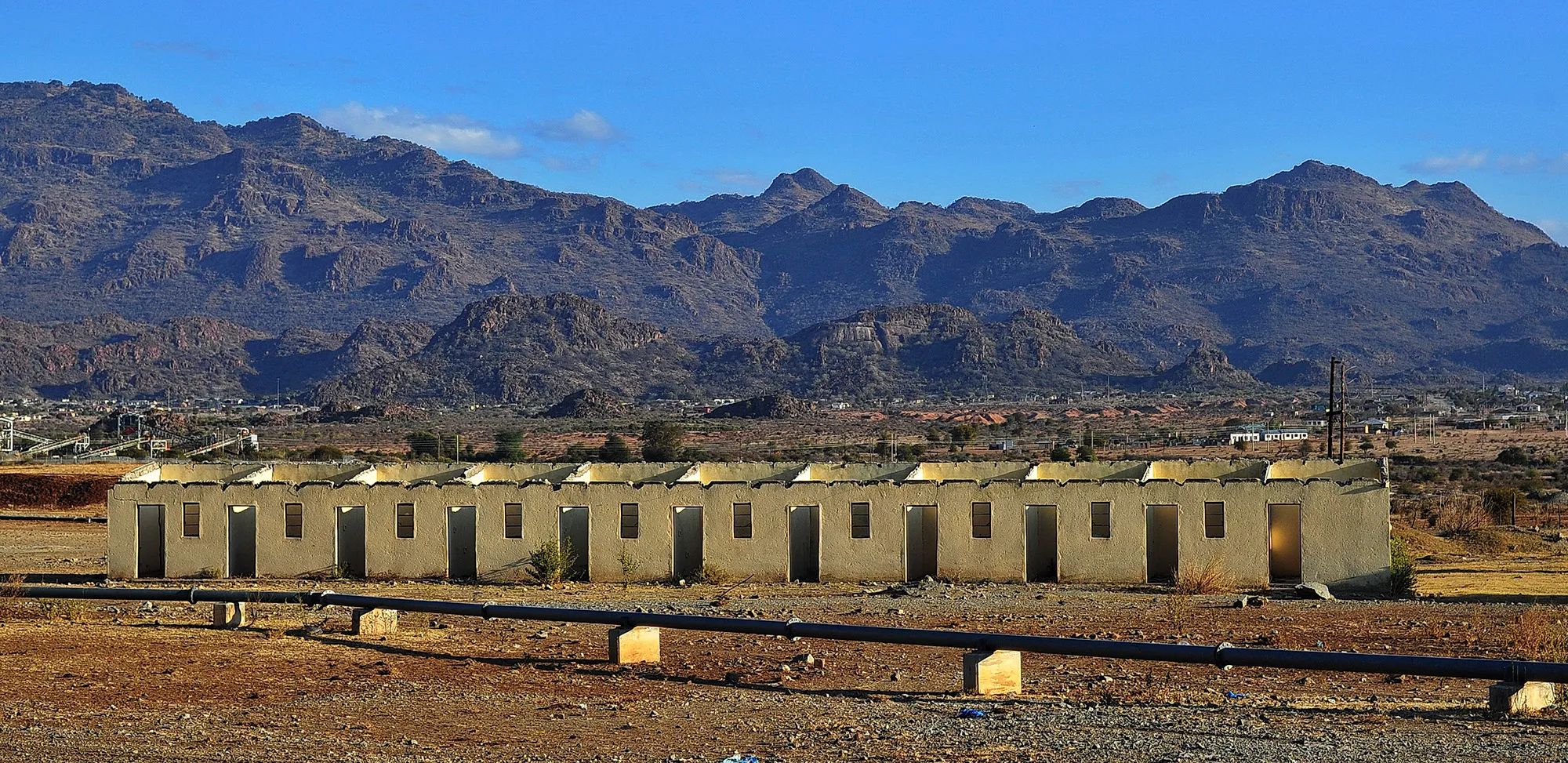

Hard times have hit the villages of Atok and Monametsi whose economy has for the past 50 years revolved around the Bokoni Platinum Mine which has since shut down. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Other businesses that thrived as a result of the economic activity created by the mine, such as car washes, fast food outlets, taxis, taverns and spaza shops, have also been hit hard. There are even reports of a car wash operator who suffered a mental breakdown after the demise of his once-popular business.

The village’s rental units, once teeming with people, are now deserted and most are falling apart. Residents speak of rising crime and stock theft.

According to the villagers of Monametse and Ga-Mokgotho there was no proper information relayed to the communities and no efforts were made to prepare them for life after mining.

Vandals are stripping accommodation units that have been standing empty since the closure of the Bokoni Platinum Mine in Atok, Limpopo. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Said Manala: “When Bokoni Platinum Mine was still operating I used to make lots of income from my tenants and could even afford to send my children to school with the hope that one day they will be employed at the mine. [I was able to] pay policies [village societies] and put food on the table, but now things are bad. We only survive on a tuckshop, although customers are very scarce.

“The announcement of the mine closure left us in shock. Everyone appeared to be rather fragile or vulnerable, as the mine has not prepared us for the sad news,” she said.

Due to the lack of tenants and loss of income, she has been struggling to maintain the rooms. She has even destroyed some of them to create space for a food garden.

She blames the mines for causing the devastation in the community.

Helen Manala had more than 50 accommodation units let to mineworkers in Atok. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

“Our houses have been cracking because of the daily blasting and the frequent passing of haul trucks in front of our houses. The mine has promised to repair our cracked houses. The last time we heard from them was when they collected our names for the database, promising they will come back. We are still waiting,” Manala said.

“Even the food garden is not productive because the soil is not fertile and it needs manure, which is costly,” she added.

Villagers depend on severance packages, support from relatives, finding jobs elsewhere, food gardens and engaging in informal sectors to survive.

Nobody’s home as the village of Monametsi experiences exodus after the closure of mine shafts that were the lifeblood of the village and surrounds. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Over the 50 years of platinum mining in the area there had been hope that the mine would provide long-run potential to generate sustainable economic prosperity in the region. However, rather than being a symbol of a long history of mining that has supported prosperous and healthy communities, it has been a symbol of the opposite: a region of persistent and deep poverty, unemployment and a lack of infrastructure development.

Peggy Mashaku, like any other parent trying to find means to put food on the table for her four children, also resorted to building rental rooms.

“I started building them in 2002, with two mud house rooms after my parents passed away, to support my siblings and my own children. In 2009 I extended the rooms to six, using block bricks which I made myself. There still are bricks piled up in the yard. I was hoping to use them to extend more rooms because demand for rental rooms was growing – until we got the shocking news that the mine is closing,” she said.

Mashaku used some of the proceeds from her rental business to send her children to school, hoping they would complete their studies and find jobs at the mine. Due to lack of income, her daughter has had to drop out of college.

The closure of Bokoni came as a shock to her. Her tenants left the rooms one by one, until they were completely empty.

The owner of this unit in Sefateng used to make R3,000 a month from letting them to mineworkers, but has now lost all that income and has to rely on government social grants for survival. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

A landlord who wanted to remain anonymous had been staying in Sefateng village for 44 years, with mining as her only source of indirect income. She started her rental room business in 2000 with two mud rooms and extended these to nine rooms in 2007, also using block bricks.

“People have no source of income. Our children were forced to go out to other areas to look for greener pastures, leaving the mine. It is difficult for them because now they have to pay rent and transport and support us,” she said.

Limpopo is known as the economically poorest province in South Africa, although it is rich in biodiversity and natural resources. Mining yields important quantities of coal, copper, diamonds, gold, iron ore, nickel, platinum group metals, rare earth minerals and tin to South Africa’s mineral industry.

The 82 mining projects in Limpopo that are currently listed on Africa Mining IQ’s online database contribute about 30% to the provincial gross domestic product.

Roads that used to vibrate under the weight of mining trucks carrying ore are now deserted. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

In 2012 the Presidency launched the Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Revitalisation of Distressed Mining Communities. Its mandate was to oversee the implementation of integrated and sustainable human settlements, improve living and working conditions of mineworkers and determine the development path of mining towns and the historic labour sending areas.

The Presidency said R18-billion was dedicated to ongoing work in distressed mining communities benefiting the Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West.

However, communities like Atok have yet to see any benefits from these plans. Although there are currently 35 operating mines in the Greater Sekhukhune District extracting chrome and platinum, which is contributing to over a fifth of the region’s entire economy, the area remains among the poorest in the country. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider