What’s past, is prologue

Back in the 1930s, in the midst of The Great Depression, “The Cowboy Comedian” Will Rogers (an avid supporter of the Democratic Party, President Franklin D Roosevelt and his administration’s “New Deal” economic recovery policies) could always bring down the house when he delivered his trademark punch line: “I am not a member of any organised political party. I am a Democrat.” Given the intra-party struggles within the Democratic Party then and now, that internecine warfare has barely changed since Rogers’ time.

Aside from the personal rivalries that are the coin of every political party (South Africans are certainly familiar with that version of politics), a key reason for this intra-party political strife among Democrats is that the party — actually the oldest continuously existing political party in the world — has always been that it is a coalition of diverse groups and interests, in addition to a general adherence to often-vague, basic principles. (Historically, the party has reversed some of its original positions ever since Thomas Jefferson founded it, in light of the nation’s changed circumstances, challenges and leadership.)

“The Democrats dominated US politics from the 1930s through the 1960s because they included all kinds of people, from Southern segregationists to Northern liberals...”

The precise composition of the Democratic Party’s coalition has changed over time, and it has continued to evolve in response to changes in the national economy, external threats and the country’s demographics. (Jefferson had originally envisioned a party of sturdy yeoman farmers. He distrusted the cities and the growing role of the business class, and he wanted to maintain a small, limited government.) The reality is that the party is an often-unruly coalition, per Will Rogers, that often only warily fully coalesces in service of electing candidates and opposing its opponents. A distinct, pristine, pure ideology may take second place in all this for many supporters.

In response to the grave national crisis of The Great Depression, in the stretch of its most successful run of elections, in the era between 1932 to 1964, the coalition had bound together Southern segregationist political barons, white Southern and Midwestern small farmers and small businessmen, and the Northeastern and Midwestern working class and urban, ethnic constituencies, including northern blacks, unionised labour in factories, mines and railroads (including the all-black union of pullman sleeping car porters). The party became home for advocates for then-distinctly leftwing socialist measures (or something very much like that). And it included a coterie of public policy intellectuals, often drawn from the country’s small, but politically active Jewish population imbued with the traditions of leftist activism carried over from the Old World they had fled from earlier.

As Fareed Zakaria had also written in his most recent column: “The Democrats dominated US politics from the 1930s through the 1960s because they included all kinds of people, from Southern segregationists to Northern liberals. It was a Faustian bargain, but that coalition rescued the country from the Great Depression and passed Social Security, Medicare, food stamps, Head Start and a host of other programs that helped Whites and minorities alike.”

In the South, most especially, Democrats had been able to count on nearly-automatic support at the ballot box (by whites only) for nearly a century after the Civil War had ended in 1865. But this broad Roosevelt coalition was something new in American politics and it provided the basis for Franklin Roosevelt’s four wins, Harry Truman’s subsequent victory in 1948, and John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson victories of 1960 and ’64. Dwight Eisenhower’s two victories in 1952 and ’56 are explained by his wartime fame, fatigue with a seemingly unending Korean conflict, and a public ennui with nearly continual Democratic presidents.

The components of the Roosevelt coalition stayed loyal to the party for decades, well into the early 1960s — save for two twin revolts by segregationists and hard left liberals in 1948 respectively under South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond and then former cabinet member Henry Wallace, in revolt against a civil rights plank in the party’s campaign platform for Thurmond, and a push for a more accommodationist policy towards the Soviet Union by Wallace. However, beyond the broader changes in the national economy, the party’s unity increasingly faltered in a backlash against a growing push by Northern liberals for the civil rights legislation that would break down the legal bases of racial segregation.

This gave the Republicans, via Richard Nixon’s 1968 “Southern Strategy”, an opportunity to seize the loyalty of Democrats in the South, especially as the third party protest candidacy of arch-segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace began to dissipate. By then, the allegiance of other elements of the Democratic coalition was weakening as well. The growing middle class “suburbanisation” of the American urban population led chunks of a formerly urban, solidly Democratic working-class population to move towards supporting Republicans. Moreover, the shrinking share of the economy represented by unionised industries with their Democratic Party-supporting, unionised workforce further encouraged the defection of another key pillar of the party as many of these individuals no longer felt the ancestral tug of party loyalty.

By the 1970s, beyond the loss of support in the South, successive failures of the progressive-liberal (and presumably elitist) presidential candidacies of George McGovern, Michael Dukakis, Walter Mondale and John Kerry focused attention on the weakening of the party’s old allegiances. Party leaders sensed Democrats could only succeed in a presidential race if they nominated racial and economic policy moderates who were Southern governors, such as Jimmy Carter or Bill Clinton if they hoped to build a modern, winning version of the Roosevelt coalition.

Why we are where we are now

When Barack Obama ran for president in 2008 and 2012, Democrats were increasingly cheerful he had crafted the correct strategy to forge a new and lasting electoral coalition. As a foundation, it would build on the large numbers of new voters in the latest generational cohorts, the rising political heft of African-Americans, Hispanics and other minorities, along with the cohort of largely white, middle-class, university-educated, suburban women increasingly poised to move beyond traditional ties to establishment Republican politics.

By the time Donald Trump ran for president in 2016 against Hillary Clinton, the gap between Democrats and Republicans in terms of political support from women had become seriously lopsided in favour of Democrats. While the Trump candidacy could capitalise on a special kind of populist revolt — largely among white, high school-educated, working and middle-class men angry at a governing class that seemed to be ignoring their anguish in the face of shrinking employment opportunities — it was also fed by racial antagonisms.

Despite this anger, it remains unclear such a support base can be an enduring electoral coalition in the manner of either the earlier Roosevelt or more recent Nixon/Reagan years. As a result, this election of 2020 now represents a potential clash of competing visions about a stable governing coalition for either party.

2020 and all that

For Democrats, their 2020 nominating convention was going to demonstrate just such a new, winning coalition and to blur the divisions within the party. This was to be the case, despite significant divisions over the relative importance of policies pushed by the new left wing of the party. There could be an angry fissure between the old centre-left exemplified by Joe Biden, versus the progressive-leftists in the Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez wing of the party.

It became a four-day, two-hour-a-night mini-series as a festival of inclusivity, with star turns by big names and ordinary citizen unknowns alike.

Given the bitter experiences of Trump’s four years, the centre-left wing now focused on attracting independent voters and even a sizeable share of nominally Republican voters, even if it meant soft-peddling support for some of the measures touted by the progressive-leftist. For its part, the progressive-left seemed to believe it was more important to build support for a laundry list of its favoured policy ideas — even if that might risk losing hope for support from the undecideds or nominally Republican voters. (As noted earlier, this is not the first time such a division had broken out in the party. Recall the Henry Wallace walk-out of 1948, or, more recently, the movement of the party to support ultimately losing candidates like McGovern and Dukakis.)

The primary contests eventually boiled down to a struggle between the former vice president, Joe Biden (now on his third effort to gain the nomination), and Vermont’s democratic-socialist senator, Bernie Sanders (his second run at the nomination). The Sanders campaign counted on harnessing the enthusiasm of younger constituencies and heretofore marginalised communities for more fundamental changes in the country’s economic landscape.

By contrast, the Biden camp came to recognise that in the primaries, he would win or lose by gaining support from more centrist-style voters and, crucially, from the African American (increasingly female) base of voters who were loyal backers of Democrats. But by the time the primary season had ended, it was clear the Biden forces had actually gained significantly more total voters than Sanders had done and, in fact, Sanders’ total support was measurably lower than it was four years ago.

The task, going forward, then, for Biden and his team was to script a convention that demonstrated inclusivity, rather than a controversial, disruptive convention as had happened at times in the past for Democrats. There would be no sectarian, agenda-driven floor fight over platform provisions or candidates — let alone the possibility of a walkout by those disaffected by the now-inevitable outcome.

But then, enter Trump’s hat trick. The Covid-19 pandemic has continued to cut through the country, killing nearly 200,000 people and sickening millions more, even as disconnected, belated efforts to contain it has caused immense economic harm to many millions more. Moreover, from early summer onward, the racial turmoil stemming from outrage over police killings of younger black men after minor infringements of law did not die out — leading to protests across the nation, in tandem with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Given the pandemic, the original design for the Democratic convention in Milwaukee — picked because it boasted a long-time progressive tradition, a strong labour movement and its electoral significance as a must-win state — had to be scrapped. Suddenly, it had to be completely reengineered into a nearly all-virtual event.

It became a four-day, two-hour-a-night mini-series as a festival of inclusivity, with star turns by big names and ordinary citizen unknowns alike. The end result gave new life to a creaking formula, making it something of an adventure to watch (and for cynics to wait to see if the whole programme might collapse). Instead of the usual stemwinder of a speech, the keynote address featured over a dozen different people with short contributions; the voting by delegates on the nomination was live-streamed from 57 scenic locations across the states and territories; and speeches from activists working to improve comprehensive medical care, implementing gun control and focusing on environmental concerns.

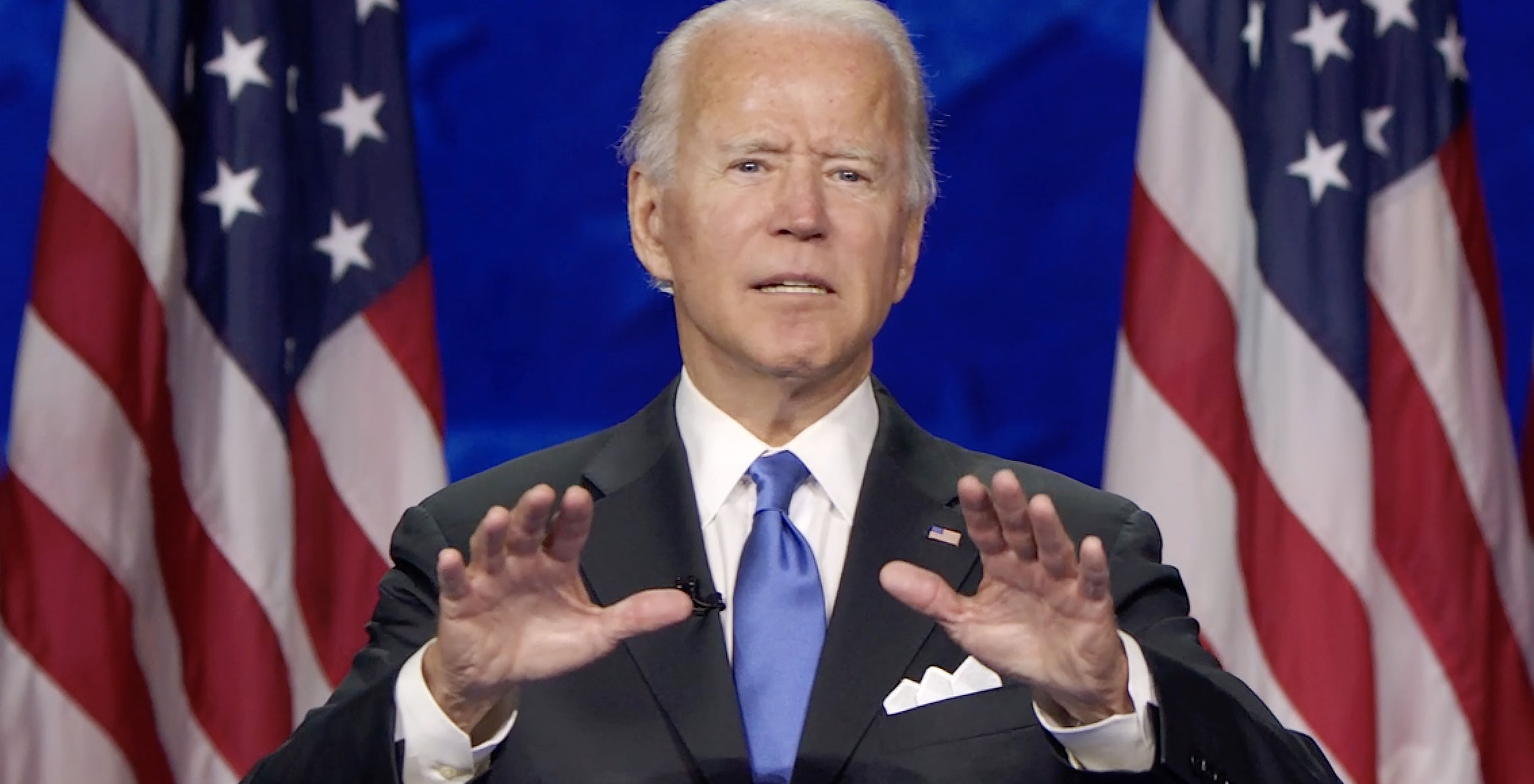

But much expected highlights were speeches by Michelle Obama, Bernie Sanders, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Kamala Harris and Jill Biden. And Joe Biden’s formal acceptance of the nomination came right at the end of Thursday night’s proceedings where he hit a home run.

Michelle Obama offered a plangent conversation, almost as if she despaired that Trump had simply been unable to grow into the job he had taken, and had, instead, led the country in some dark, dangerous place. Sanders, meanwhile, compared Trump to Nero — the Roman emperor who fiddled as Rome burned, while Trump had gone off to play golf. In his speech, Bill Clinton lamented the divisive, economic collapse, and Jill Biden gave a truly warm, gracious, self-introduction that offered her life — and her husband’s — as models for being engaged with people’s real cares and fears.

width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen">

Largely unknown to most people despite having been in the public eye for years, Jill Biden came across as a mensch, who had built a life with a man who would lead the nation — even as she pursued her career in education. Hillary Clinton reminded her audience that getting supporters to the polls is the most important thing, given the way the electoral system can reward a candidate who squeaks by in enough states to win the electoral college vote even while losing the popular vote (and she would certainly know something about that).

The prerecorded inserts of Biden on the train to and from his home in Wilmington to Washington every day portrayed a man who had really made friends with train staff, while the woman he encountered on an elevator frequently was so enthusiastic, she had been asked to second his nomination. Similarly, Senator Kamala Harris gave a self introduction designed to reveal her softer side, her inner life, and her family history, as well as the values she has stood for as a politician and prosecutor. But she also prosecuted the case against Trump.

As Washington Post columnist EJ Dionne observed: “In keeping with expectations that a vice presidential candidate will strike relentlessly at the opposition, Harris continued to online the Democratic National Convention’s assault on President Trump’s failures, lies and selfishness. But as prosecutors sometimes decide to do, she chose to speak not angrily or irritably, but in a tone of quiet sorrow over a country confronting pain, distress and exhaustion with a divisive and erratic president.”

epa08615688 A framegrab from the Democratic National Convention Committee livestream showing Joe Biden speaking during the final night of the 2020 Democratic National Convention (DNC) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, 20 August 2020. The convention, which was expected to draw 50,000 people to the city, is now taking place virtually due to coronavirus pandemic concerns. EPA-EFE/DNCC

epa08615688 A framegrab from the Democratic National Convention Committee livestream showing Joe Biden speaking during the final night of the 2020 Democratic National Convention (DNC) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, 20 August 2020. The convention, which was expected to draw 50,000 people to the city, is now taking place virtually due to coronavirus pandemic concerns. EPA-EFE/DNCC