Almost 20 decades ago, just north of Alice in the Eastern Cape, the Lovedale Missionary Institute was founded. As Mwelela Cele writes for New Frame, 46 years later, “more than 2,000 black students had successfully completed their secondary education at Lovedale”. The influence of the institution on South Africa’s political, cultural and intellectual life throughout the years is prodigious; from one of the first black woman journalists in the country, Daisy Makiwane, to poet Isaac Williams Wauchope and journalist, Xhosa hymn writer, musician and composer of Vuka Deborah, John Knox Bokwe, and anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, Lovedale nurtured generations of prominent intellectuals, and political leaders.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-08-16-preserving-lovedale-press-a-historical-compass/

In 1823, the mission opened the Lovedale Press, publishing educational and evangelical isiXhosa texts and literature, as well as the institution’s newspaper Ikwezi and journals like Bantu Studies. The press was destroyed in the Frontier War of 1834-1835 and rebuilt in 1861 and since then, kept printing and publishing literary works by black writers, authors and musicians, assembling one book after another, a library of absolutely vital function.

Today, the concrete structure that holds the press could easily be mistaken for a rather minor building if it wasn’t for the plaque on the side of the main entrance, a quote by novelist A.C. Jordan, with the words: “The earliest record of anything written by any Bantu-speaking African in his own language in South Africa was made at the small printing press at Old Lovedale.”

In 2020, Lovedale, which survived a war, apartheid, threats of closing down, auctions, more threats and the slow-burning disappearance of the printing world, is still standing, 197 years after its opening.

Says artist Athi-Patra Ruga on visiting the site: “The front is nondescript. It has a landmark sign, but not a heritage site sign. It’s just a tourism sign saying that here is the Lovedale press… There is nothing digital… There are boxes of wrapped-up books and textbooks… Rain damage is happening on some publications that were printed there.”

In 2020, Lovedale, which survived a war, apartheid, threats of closing down, an auction, more threats and the slow-burning disappearance of the printing world, is still standing, 197 years after its opening; and yet, although the press is kept active, operated by three former employees – now the owners of the Lovedale Press, Bishop Nqumevu, Bulelwa Mbatyothi and Cebo Ntaka – the institution is once more on the verge of closing; books in brown paper are piling up to the ceiling like fragile structures, a metaphor for the vulnerability of the place. It’s an Ali Baba cave of sorts, but filled with words that together write the story of our country – should it disappear, it would be a loss of significant cultural memories in written form.

“I went to Johannesburg as part of ‘the realness project’, which is a film-making workshop that happens in [Nirox]. I was developing The Lunar Songbook Cycle, which revolves around a child prodigy, who lives in the imaginary world that was set by the Lovedale press; 200 years of history that lives through the body of Nomalizo Khwezi, who is this character I’ve been working with, both in art exhibitions and also for this film that I’m developing,” says Ruga.

Indeed, in his new series, Interior/Exterior and Dramatis Personae, which is currently exhibiting at the Whatiftheworld Gallery in Cape Town, the showman and artist tells the tales of two characters, Nomalizo Khwezi and Nestra Brink, both inspired by the literary work found at the Lovedale Press.

For two years, Ruga had been speaking with actress and academic Lesoko Seabe, as they share a passion for language and the arts; they also understand the urgency to preserve, protect and bring to light memories, and markers of time and culture, especially black culture, languages and literature.

In 2019, Ruga travelled to Alice, down to the Lovedale Press, to learn more about one of the subjects he was working with. “I remember leaving the place quite heartbroken, because there was no way in which in 2019 anyone could actually have access to it because of circumstances… And the circumstances were that of electricity, that of pay points, that of running water, that of insurmountable debt in the form of rent…,” he says. That’s when he first met the three owners of the press, Nqumbevu, Mbatyothi and Ntaka.

Together, Seabe and Ruga, with the consent of the Lovedale team, started playing around with ideas and possibilities to build awareness of the place; and then, the Covid-19 pandemic obscured the world with an ominous and scary cloud.

You must be shocked and then you must act.

“The art had met reality in the sense that Covid made us think of people; and we started the Victory of the Word there and then, on a kitchen table. We said, let’s bring attention to the place, let’s bring attention to the fact that it does need help to sustain itself for the next 200 years,” says Ruga.

“It is not the first time that Lovedale has had this kind of a moment. I’m aware of at least two other fundraising efforts that have really tried to galvanise people’s energies towards saving this really important historical institution. And what’s been interesting is that in this particular iteration, when Athi and I have been talking about it, people can’t believe it; they can’t believe that an institution of that stature, with this kind of contribution to intellectual life, to political life, to art life in South Africa, is in this kind of a crisis,” adds Seabe.

In fact, for an institution like Lovedale to still be in crisis today seems improbable – it’s easy to assume that a place with such historical consonance would be receiving some sort of help, be it from governmental organisations or local agencies; but Lovedale is also a privately-owned company and help is not guaranteed especially if not asked for.

“It’s almost 200 years old. It has all of this significance, politically, education-wise, a part of our national anthem was first published there, so it almost seems like a no-brainer. But again, what is that process? Does Lovedale itself have to apply for that? Was there an application that was put forward and was rejected for whatever set of reasons? But in my mind, it should be something that you know, the Department of Arts and Culture, or the heritage agency, should nominate, and say, ‘you are this incredible institution; here is the process; here are the forms, let’s make this thing happen’. I think that would be a logical thing for me, but that hasn’t happened,” says Seabe.

“What was important for Athi and I is that once we got over our shock, and our dismay, and our grieving that this is a moment that we are even facing, we had to move into action. It’s something Athi said right at the beginning, ‘you must be shocked and then you must act’.”

And so, they acted: They launched a fundraiser campaign through the online platform backabuddy; by the time of publication, it had raised over R67,000. The money will help pay employee salaries.

“The thing that has moved me the most is that, at a time when citizens are really looking after their finances, when people are losing their jobs in such dramatic ways, that people are still finding what they consider small pockets of money to contribute to something that they feel is worth saving. And they also see the benefit of looking after the people who look after the institutions first,” explains Seabe.

Beyond the fundraising campaign, they have engaged with “some really smart financial and strategic minds”, to help them think about the next steps, and to ensure this won’t be another stop-gap campaign that might only help the press in the short-term.

“We’ve also engaged with a smart pioneering woman in the African publishing space, who thinks that Lovedale and publishing in the way that we want to do it, really does have a future and is necessary in South Africa and on the continent,” says Seabe.

“I think that with the dying of vernacular, we need to find futuristic ways in which we can build industries out of translation, because that’s what needs to happen for it to be activated, we need to have much more futuristic looks,” adds Ruga.

The idea is to think about how the space, the physical press and the Lovedale archive can be used, beyond preserving and highlighting what Lovedale represents.

Seabe ponders: “Would IsiXhosa in the written form look like something else had the press not come? These are the questions that we can then have really wonderful intellectual moments about; and then start to reimagine what the press can do, what other kinds of artistic outputs can occur out of the artistic space. In terms of the archive itself, the books that have come through the press: the bibles, the hymns, Nkosi Sikele’ that was first published at Lovedale! All the incredible people who have gone through Lovedale: the first doctors, lawyers, engineers… were first educated at Lovedale college, which has this close relationship to the Lovedale Press. Where are the pieces of the archive? And which parts of the archive have gone missing?”

She adds: “I listened to a wonderful speech that you can actually still find online, by one of the old principles, Reverend Shepherd, who talks about parts of the archive going to the University of Cape Town, parts of the archive, just being written down on diaries and being taken by wives of ministers and pastors, and going back with the missionaries; there are also some kind of rumours that go along that some of the principals there didn’t agree with some of the work that the writers at the time were producing.”

The project is a work-in-progress, and both Seabe and Ruga agree that a phased approach is essential in order to shape the future of the Lovedale Press, which includes raising money, creating sustainable revenue channels, rebuilding the publishing house and translating original historical works.

Seabe says that although they’ve been wanting to know what went wrong in the past and why the press is in crisis again, they have to focus on what is needed today and what they can do differently.

“It was therefore important for Athi and I to conceive of a long-term fundraising and development plan… Phase one, which we are currently in, seeks to reignite the imagination around this historic space using social media and to pay collective tribute in the form of an honorarium, with money raised through the back a buddy campaign, to the remaining custodians who have managed to keep the doors of Lovedale Press open. Phase two is about stabilizing the business and phase three is putting into action a reimagined, profitable, sustainable arts business that is responsive to the current climate and that can exist beyond its 200th birthday in 2023.”

“We thought about what part of our community would always need access to these kinds of books, and we were thinking about collaborating with the Department of Education, as they make this push towards the foundation-phase learning in indigenous languages, and to be a primary developer of those works; so that we could then help provide, disseminate and publish those works for Grades R to 3. If we could get that contract or parts of those contracts to generate that income, that would allow the different other parts of the business to be taken care of.

“We would love to have seminal works reprinted to expose a new generation of readers to the works that were produced at Lovedale and to create a space where writers can publish new original material in the indigenous languages of Southern African. This a one way in which we can add to the archive of Lovedale and not only reference it or derive from it. Podcasting and webinars could help us engage archival and future materials with audiences locally and internationally. You can’t escape it, part of the process of saving Lovedale has to involve digitalization. Lovedale Press will not survive if it only thinks of itself in analogue terms,” she adds.

We’re a country whose preamble, in every aspect that we do, is to right the wrongs of the past.

Ruga concurs, adding that both the Department of Arts and Culture and the Department of Education could help in declaring the place a national heritage site – at the time of publication, SAHRA, the national heritage resources authority, had not responded to our questions.

“200 years is too long,” he says.

“The second thing that they can do is facilitate a way in which the property, or the intellectual property, or the actual archive that is there, be known. Because a museum cannot just be a building that lasts; a museum needs to be frequented. If there would be a museum attached to the press, it would need to be frequented. With regards to the books: what is the syllabus? What are the kids learning? Is it contemporary books that are written into Xhosa language or is it the classics? Or is it a mix of both?

“We’re a country whose preamble, in every aspect that we do, is to right the wrongs of the past. And one of the major ones and the most consequential one is the erasure of people’s cultures. The Department of Arts and Culture, the Department of Education are here to help in righting those wrongs, or facilitating for the redress of those situations. And that’s where they come in. At the moment, Lovedale in whatever state it exists, is in trouble. It has so much intellectual property that has added to the dignity of the people, me included; my art included,” says Ruga.

“I’m in a position whereby the story has fed me, the stories that come from there have literally fed me and Lesoko and many generations. I left there wanting to get as many people as possible to do even a simple thing like acknowledging the place. And hopefully it sticks this time. We’re just praying it sticks this time.”

What do they hope the campaign will achieve? “I think that the first thing that people can do is Google and research as much as you can about the Lovedale Press and other presses that were involved in the development of contemporary indigenous language in South Africa. You will learn so much; because it goes beyond the modern founding myth of South Africa. It’s us loving in our own languages; it’s us praying in our own languages; it’s us living, so that humanity just finding out about Lovedale… it gives you a backbone.

“The next thing, if you live in the Eastern Cape and you’ve got petrol and you can travel, please go visit them. And if you are there, please make the sacrifice of bringing a lot of money, probably R1,500, so that you can buy the catalogue for the future. We all need a library and these books are not available in digital form yet, so go buy them if you’re in the Eastern Cape.

“We’re also trying to just get people to reattach again to this space. Because those sales could go to the day-to-day living of the people so that they have the strength to carry on. That’s all I’ve been thinking. That’s all we’ve been thinking, the strength they need to fight well. They need to fight well…,” says Ruga.

Seabe nods, smiles and sighs. Their passion and love for the place are palpable, and contagious. It’s an all-consuming undertaking, especially as both the actress and the artist have full-time jobs and not much time to spare working on other projects. But it’s a labour of love, she says, and a “dream that lives so close to the heart… and so close to the flesh”.

Now, after almost 200 years, a history so rich, it turned a small missionary institute into a national treasure. With thousands of pages printed and bound together, will the word finally be victorious? It has to be. DM/ML

Disclosure: Malibongwe Tyilo, Maverick Life Associate Editor, is Athi-Patra Ruga's life partner.

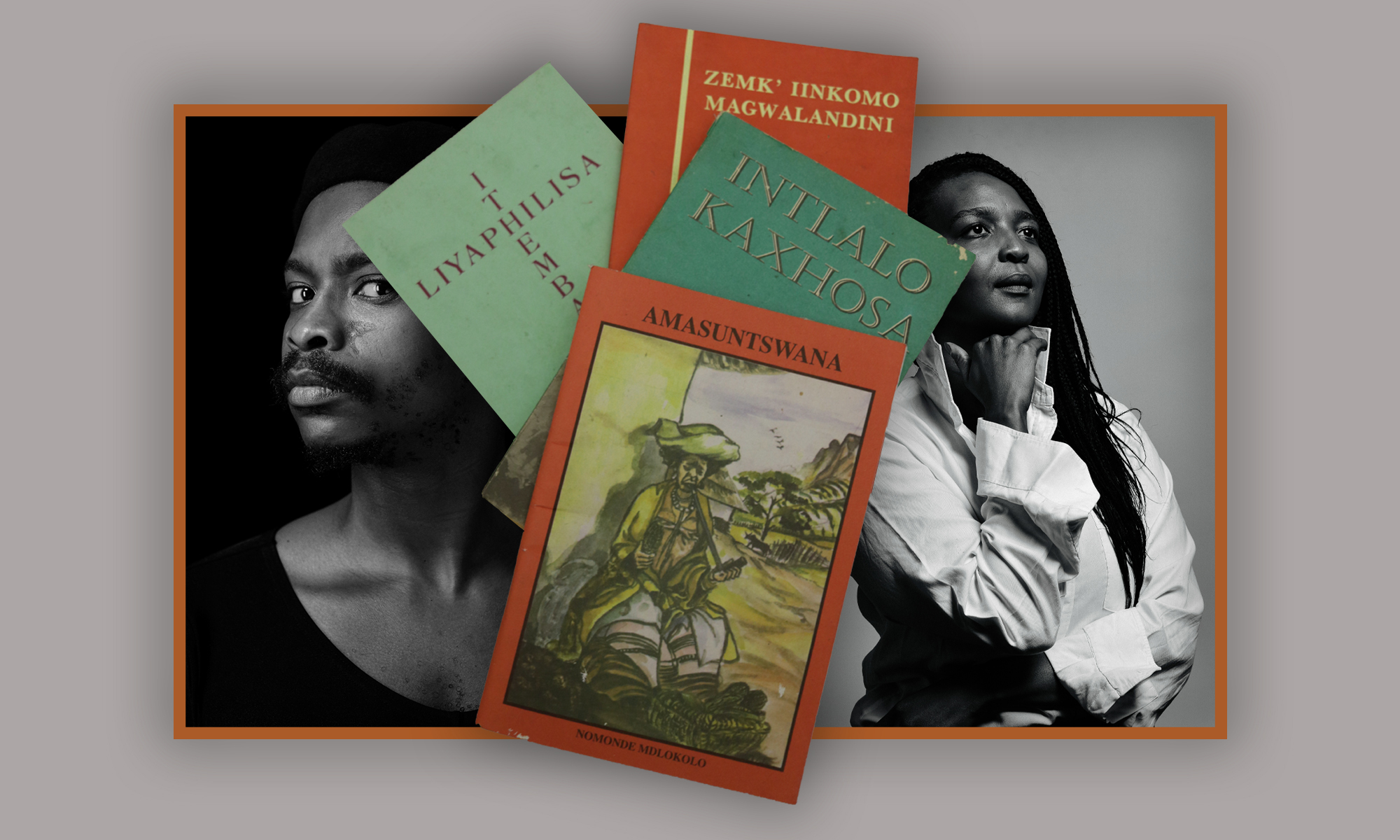

Image design by Malibongwe Tyilo for Maverick Life; Portrait of Athi-Patra Ruga by Rene Habermacher; Portrait of Lesoko Seabe by Gerald Machona

Image design by Malibongwe Tyilo for Maverick Life; Portrait of Athi-Patra Ruga by Rene Habermacher; Portrait of Lesoko Seabe by Gerald Machona