Open Secrets: Unaccountable

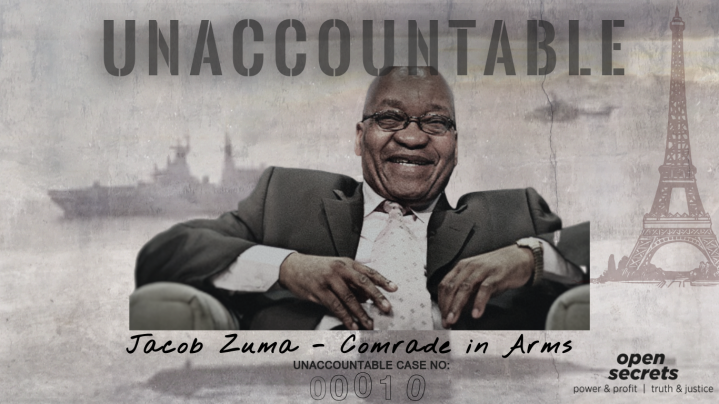

Jacob Zuma – Comrade in Arms

This week Open Secrets publishes the first of a number of profiles on the corporations and middlemen implicated in the multibillion-dollar Arms Deal of the late 1990s. None of these companies has been held to account.

The arms in the infamous Arms Deal were bought when South Africa faced a different viral health crisis for which we could ostensibly not afford medicine: HIV/Aids. While hundreds of thousands of people died unnecessarily, and even more lost their jobs, the country bought weapons we did not need and could not afford.

The evidence which exists in volumes shows that corruption was a primary driver for the Arms Deal. As The People’s Tribunal on Economic Crime has found – this was the bridge between the economic crimes of apartheid and the State Capture of recent years.

This week we start the focus on a nominally retired politician whose struggle to avoid accountability for his alleged complicity in these crimes is now legendary.

***

For more than a decade, former president Jacob Zuma seemed deeply conflicted in how to confront his alleged complicity in the Arms Deal. He has demanded his “day in court” while he and his lawyers infamously use every possible means to prevent that day from happening. As South Africa was preparing for a lockdown to try and stop the spread of Covid-19, he played what might be the last card in this “Stalingrad strategy” – an approach to the Constitutional Court to obtain a permanent stay of prosecution.

However, just last week, Zuma, aided by yet another new lawyer, changed strategy and dropped the appeal (while the French arms corporation continues a battle on this front). Is he finally ready to defend himself in open court or is he going for broke with his nagging threat to out others who benefitted from these corrupt deals?

Let’s first turn to the facts.

After a decade of a scandal-ridden presidency by Zuma, and the catastrophic impact of State Capture under his watch, it is easy to forget that these efforts have been almost entirely dedicated to ensuring he remains unaccountable for alleged crimes committed before he was president.

Zuma’s long and most tumultuous run-in with the law actually relates to his role in the 1999 Arms Deal – not his relationship with the grifters in the Gupta family. He stands accused of 18 charges of fraud, corruption, racketeering and money laundering, related to 783 payments made to him by convicted fraudster Schabir Shaik. His co-accused is the South African subsidiary of the mega French arms company Thales (previously known as Thomson-CSF), alleged to have bribed Zuma to protect itself from prosecution in relation to the deal.

The failure to hold Zuma and these corporations to account for their alleged crimes has had far-reaching consequences for South Africa’s young democracy. Zuma and his allies inside and outside the state have contributed to delaying legal processes, deferring justice, and undermining key institutions. Together, this has created a culture of impunity which has enabled opportunities for current-day State Capture.

The Arms Deal

The final agreement sealing the 1999 Strategic Defence Procurement Package – the infamous Arms Deal – was signed on 3 December 1999. It was a deal that locked South Africa into two decades of insurmountable debt in the form of loan repayments and interest fees. At the time, the Arms Deal, already surrounded by controversy and allegations of fraud, corruption and impropriety, was the largest foreign acquisition undertaken by South Africa’s democratic government.

At the time, R30-billion was spent on these new arms acquisitions. However, this value was at the 1999 exchange rate and did not include two decades worth of costs related to the financing of the deal such as fluctuating interest rates, transfer costs and other repayment fees. 2020 is the year that the final repayments for these Arms Deal loans are scheduled to be made. Readers of this column will channel tax monies in one form or the other this month which will go towards repaying this historic debt.

A full and total disclosure of the real cost of the deal has never been formally made, leaving us to rely on estimates. The best estimate is that upon final repayment the total cost of the deal from 2000 to 2020 will be between R61.5-billion and R71.68-billion, while other estimates have this value closer to R100-billion. Adjusted for inflation, the figure is much higher, and may be up to double these estimates.

If we take the upper figure, it is equivalent to every South African alive today forking out close to R20,000 for a corrupt project that has damaged our democracy and its people.

It should be emphasised that this multibillion-rand deal was made at a time when South Africa should have been ramping up efforts to combat its growing HIV/Aids epidemic. Just years before, the then-health minister, Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, claimed that an ARV programme that would combat mother to child transmissions, was too expensive to contemplate. At the time, for every R1 spent on the HIV/Aids programme (including providing antiretrovirals), R7.63 was spent on the Arms Deal.

Apart from the extortionate cost, it is unclear that the weapons were needed at all. The White Paper on National Defence presented by Parliament and approved by Cabinet in 1996 – one year before the 1997 official start of the Arms Deal acquisition process – clearly acknowledged that there was no military threat to South Africa. In fact, The White Paper emphasised that South Africa’s focus had shifted from a military offensive approach, to an approach which allowed for the needs of the population to be prioritised as “poverty [w]as SA’s biggest risk to national security”.

Yet, as is too often the case, profit was placed above the most basic needs of South Africans. The notoriously dirty global arms trade, where arms companies dole out billions in bribes as a cost of doing business, ensured ample opportunities for self-enrichment within leadership. This trumped the need for social welfare and housing projects.

Jacob Zuma and Schabir Shaik – the part-time businessman and full-time fraudster

Allegations of corruption related to the Arms Deal have been ventilated in South African courts. In 2005, the late Judge Hilary Squires convicted Schabir Shaik on charges of fraud and corruption, and described the relationship between Shaik, Zuma and Thales as a “mutually beneficial symbiosis”. As Zuma’s close friend and financial adviser, as well as Thales’ South African BEE partner in the bid to win the contract to supply the weapon systems for SA’s newly acquired warships, Shaik was perfectly positioned to act as middleman between the two, protecting their respective interests, and his own.

Shaik was charged on two counts of corruption for his role in the Arms Deal, both of which related to undue payments by him to Zuma, both before and after Zuma became the deputy president of South Africa. Shaik also faced a third count of fraud for misrepresentation of financial records related to an arm of his Nkobi group of companies.

Shaik’s first charge of corruption related to what the state called a “generalised pattern of corrupt behaviour between [Shaik] and Zuma”. The court found that from 1995 to 2002, an already cash strapped Shaik, either directly or through his companies, made numerous scheduled payments to Zuma totalling R1,282,027,63, while having full knowledge of Zuma’s financial state and inability to pay him back.

Given all of this, the court found that the “irresistible” inference was that Shaik made the payments in anticipation of some business-related benefit, that Zuma could deliver through his name, the backing of his political office and vast “political connectivity”. In its findings, the court ruled that Shaik must have foreseen that by making these payments to Zuma, the latter would continue to provide support upon which Shaik and his companies were entirely dependent.

Shaik’s second charge related to the arranged payment of R500,000 per year to Zuma from French arms company Thales. The purpose of this alleged bribe, facilitated by Shaik, was clear. In the face of looming pressure and impending investigations, Thales was to pay Zuma in order to ensure that Zuma would use his political influence to provide protection from investigative processes and to ensure that Thales would be looked at favourably for future South African projects. The alleged payment was to buy impunity and continued profits.

Again, such practices are standard in the world of grand corruption, where large corporations often buy politicians through campaign contributions or brown envelopes with an understanding that favours will be returned when needed.

Zuma’s French Connection

It is for this reason that Thales stands in the dock as Zuma’s co-accused. But Thales has a long history of flouting international laws to profit from its links to South Africa – its predecessor Thomson-CSF had a long and profitable relationship with the apartheid military and political elite, despite the compulsory UN arms embargo.

It is alleged that Zuma first entered into a formal agreement with the director of Thales’ South African subsidiary, Alain Thétard, and Schabir Shaik at a meeting in Durban in March of 2000. This was the meeting in which it was agreed that R500,000 per year would be paid to Zuma by Thales. The payments would be made through a network of Shaik’s business accounts. This agreement was reached as calls from within government and from civil society groups for an investigation into irregular procurement processes related to the Arms Deal were growing in urgency.

During Shaik’s trial, all parties denied that this meeting took place and that any such agreement was made. However, Sue Delique, Thétard’s former secretary, was able to provide evidence in the form of the now-infamous encrypted fax sent by Thétard to Thales’ sales director for Africa. The fax not only confirmed that the meeting had indeed taken place, but also that an agreement had been reached with Zuma.

In the Shaik trial, Judge Squires concluded that all parties present at this March 2000 meeting knew exactly what it was that they were agreeing to and that this payment was clearly made to ensure the protection of Thales from investigation and prosecution. The parties even concocted a code-phrase fit for a cheap spy thriller to seal the deal – Zuma was to confirm his acceptance of the bribe by saying, “I see the Eiffel Tower lights shining today.”

The full history of Thales’ long and sordid history in South Africa, and its efforts to avoid accountability, will be told in an upcoming instalment of Unaccountable.

The State vs Zuma: The long road to justice

The successful prosecution of Shaik should have opened the doors for the National Prosecuting Authority to pursue a case against Zuma himself. In fact, the final judgment mentioned Zuma’s name 471 times. However, the NPA chose not to immediately pursue a case against Zuma on the basis that the prospects of success were not strong enough.

Since then, both Zuma and elements in the state have been responsible for delaying processes and dragging this case out for the last two decades – all whilst sowing seeds of doubt and mistrust of legal systems and investigative bodies, in the minds of many South Africans.

In 2006, after his involvement in Shaik’s web of fraud and corruption was laid out in the courts, Zuma was himself charged with numerous counts of corruption, fraud and racketeering. However, after months of postponements, these charges were struck off the roll by Judge Herbert Msimang as prosecutors made repeated requests for further delays in the case, citing their unreadiness.

In 2007, the Scorpions – the predecessor to the Hawks and a successful independent agency that investigated and prosecuted organised crime and corruption – indicted Zuma on various counts of racketeering, money laundering, fraud and corruption. However, the charges were again thrown out by the courts as Judge Chris Nicholson ruled that the National Directorate of Public Prosecutions did not give Zuma a chance to make representations before charges were filed against him. In 2009, the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) rejected this argument, finding that there was no need for Zuma to be allowed to make representations before he was charged, thus allowing the NDPP to revisit charges against Zuma.

However, shortly after this ruling, the spy tapes scandal emerged. The “spy tapes” referred to the secretly recorded conversations between the former NDPP Bulelani Ngcuka and Scorpions head Leonard McCarthy, that Zuma’s legal defence would use as evidence of collusion. The mysterious and well-timed emergence of these spy tapes resulted in the conspiracy that the decision to bring charges against Zuma was politically motivated.

Zuma and his lawyers argued that there had been an abuse of process on the part of Ngcuka and McCarthy, and that the timing of the charges had been manipulated for ends other than the legitimate purpose of a prosecution. Again, these charges were taken off the table by the acting NDPP, Mokotedi Mpshe, who rejected arguments made by his own prosecutors that the “spy tapes” were immaterial to the actual charges.

One would assume that evidence of a conspiracy to quell Zuma’s aspirations of the presidency would be something he would want in the public domain. However, Zuma, his legal team and Mpshe fought to ensure that the spy tapes be kept under wraps. This prompted a near decade-long battle to have the tapes released and the charges reinstated. The reason for this fight was at least partly because their disclosure shows that the tapes had nothing to do with the substance of the corruption charges facing Zuma.

While the spy tapes battle raged on, then-President Zuma in October 2011, announced a commission of inquiry headed by Judge Willie Seriti to investigate allegations of corruption in the Arms Deal. The commission, marred by numerous high-level resignations and allegations of hidden political agendas, was labelled by many civil society organisations a whitewash.

Four years and R137-million later, the commission, which failed to consider key evidence or call important witnesses – including Zuma or Schaik – produced a report that exonerated all parties. This report has been used by Zuma and his allies to further bolster their defence. That is, until just last year, when the North Gauteng High Court set aside the findings of the commission, ruling in favour of the application by civil society groups Corruption Watch and the Right2Know Campaign.

The court found that the commission had fundamentally failed to do its job – finding “a clear failure [by the Seriti Commission and its judges] to test evidence of key witnesses [and] a refusal to take account of documentary evidence which contained the most serious allegations”.

This ruling followed a blow to Zuma’s obfuscations when in 2017, the High Court and SCA ruled that the decision to withdraw the charges had been irrational, and that the NPA must reconsider the decision. The court held that Mpshe’s decision was irrational because the contents of the tapes did not have a negative impact on the validity of the investigation, the weight of the evidence, or the merits of the prosecution. In a radical about-turn, and further evidence of Zuma’s cynical legal strategy, Zuma’s legal team conceded to the SCA that they agreed that the decision, that they had vigorously defended for a decade at huge cost to the taxpayer, had been irrational. The NPA formally reinstated the charges in March 2018.

Ironically, given their complicity in the delays and the fact that the alleged corruption was precisely to ensure avoidance of prosecution, both Zuma and Thales have continued to argue that they are unable to receive a fair trial, partly because of this delay. Both parties have submitted requests for a permanent stay of prosecution on this basis.

Crucially, in October of 2019, the KwaZulu-Natal High Court rejected Zuma and Thales’ respective applications for a permanent stay of prosecution. The judgment stated that the seriousness of the offences faced by Zuma outweighs any prejudice that he claims he will suffer if the trial proceeds. The parties appealed to the SCA, but the appeal was thrown out without hearing arguments on the basis that it had no prospects of success.

With options running out and the Arms Deal case due to resume at the Pietermaritzburg High Court in late June, Zuma made yet another attempt to avoid his day in court as part of his 15-year Stalingrad strategy. A 2020 Constitutional Court challenge, which he has now decided not to pursue, included what has been described as “a damaging admission” from Zuma’s legal team.

In the application, Zuma explains that he would only have taken the stand at Shaik’s trial if he had been guaranteed immunity from prosecution, adding that testifying “would have been ill-conceived and highly risky […] without waiving [his] guaranteed constitutional rights, including rights to silence and against self-incrimination”. This statement infers that Zuma, contrary to what he has argued for the last 15 years, is aware of his role in the crimes of which Shaik has been prosecuted. This repositioning on the part of Zuma and his lawyers may well come back to haunt them if and when his trial continues.

Who will have the last laugh?

The 1999 Arms Deal has come to serve as a symbol of the continuation of apartheid-era national militarisation and State Capture, into post-apartheid democracy. With the SCA’s decision to deny Zuma an appeal for his request for a permanent stay of prosecution, and Zuma and Thales’ next court date quickly approaching, there are new opportunities for the state and civil society organisations to hold those implicated in corruption related to the Arms Deal accountable for the extensive wastage of national funds.

Will our former president and his arms dealer friends do what they seem to do best and once again laugh off damning evidence against them, or will South Africans finally see justice served? If they do, it will be the result of years of relentless hard work and toil by those in civil society and state institutions who have gathered the evidence and struggled against those that would entrench secrecy and impunity. DM

Open Secrets is a non-profit organisation which exposes and builds accountability for private-sector economic crimes through investigative research, advocacy and the law. Tip-offs for Open Secrets may be submitted here.

Previous articles in the Unaccountable series are:

Unaccountable 00001: Dame Margaret Hodge MP – a very British apartheid profiteer; Unaccountable 00002: Liberty – Profit over Pensioners;

Unaccountable 00003: Dube Tshidi & The FSCA: Captured Regulator?;

Unaccountable 00004: Rheinmetall Denel Munition: Murder and mayhem in Yemen;

Unaccountable 00005:National Conventional Arms Control Committee: handmaiden to human rights abuse?;

Unaccountable 00006: Nedbank and the Bank of Baroda: Banking on State Capture.

Unaccountable 00007: HSBC – The World’s Oldest Cartel

Unaccountable 00008: FNB and Standard Bank- Estina’s Banks

Unaccountable 00009: McKinsey – Profit over Principle

Become an Insider

Become an Insider