Jamaican singer-songwriter and reggae star Bob Marley (1945 – 1981) outside Marylebone Magistrates Court in London on 6 April 1977, where he was fined for possession of cannabis. (Photo: Maurice Hibberd/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

‘Money is not my richness. My richness is to walk barefoot on the earth.’

– Bob Marley

Imagine Bob Marley at 75…

Would he have had long, grey, flowing dreadlocks, with a matching grey beard? Would he still have that quizzical look on his face and a Rude-Boy twinkle in eyes that perch above high cheekbones? Undoubtedly, age would have greyed and mellowed him. As in his youth, his speech would be long and languorous, still singed with a deep Jamaican patois. You need to concentrate to catch the fire in his words. At 75 he would have probably relished the mantle of elder statesman, the wizened ghetto-philosopher, composer and poet of Trench Town.

Marley might have been mellow, but he would’ve still been angry. He would still be chanting down Babylon from his Caribbean perch – 56 Hope Road, Kingston – and he would look quizzically but critically on a world that, on the surface, looks different to the one he left when he succumbed to cancer in May 1981. But is it really?

In the same week when we again mourn the murder of trade unionist Dr Neil Aggett, when we remember the death of child AIDS-activist Nkosi Johnson, Bob Marley’s 75th birthday seems a good thing to celebrate – and reflect on. For many, Marley is still close to our hearts. He was committed to our freedom in South and southern Africa. He used reggae music to free the people and, in Redemption Song, one of his last compositions (re-released by his family today) he wrote called on us to ‘emancipate ourselves from mental slavery’.

Bob predicted that equality activists would face a long War. Lifting his lyrics from a speech made by Haile Selassie to the United Nations General Assembly in 1963, he warned the world that:

Until the ignoble and unhappy regimes that hold our brothers in Angola,

In Mozambique, South Africa … sub-human bondage, Have been toppled, utterly destroyed, Well everywhere is War

In South Africa most of Marley’s albums were banned. But apartheid’s walls were porous: guns, political literature and Bob Marley albums illicitly crossed into the country where they still inspired a new generation of activists, including people like Robert McBride, who in the 1970s and 1980s were busy building MK, the trade unions, civics and the United Democratic Front (UDF).

In South Africa most of Marley’s albums were banned. But apartheid’s walls were porous: guns, political literature and Bob Marley albums illicitly crossed into the country where they still inspired a new generation of activists, including people like Robert McBride, who in the 1970s and 1980s were busy building MK, the trade unions, civics and the United Democratic Front (UDF).

Internationally, some of his songs became universal anthems, performed at human rights rallies by the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Tracy Chapman, Peter Gabriel and Sting. In the words of Fred Khumalo:

“When … Bob Marley wailed Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights, or when Peter Tosh sang I need equal rights and justice, my friends and I were startled by the directness and fearlessness of the messages. Then we were stirred into action. Some went into exile to fight. Those who stayed behind contributed in different ways towards the fight as envisaged by Marley, Tosh, Burning Spear, Culture and other reggae icons.”

Khumalo adds that, “Looking back, it’s unbelievable how art, rather than political rallies, turned us into activists.”

Yes, and here’s the rub that has made a calamity of so many progressive struggles since his death: Activists seem to forget that it’s the signs of our humanity, our vulnerability, often expressed through music or art or theatre, that can be most concientising, mobilising and awakening. That’s why the CIA was afraid of John Lennon, and probably why John Lennon reportedly listened to Bob Marley. According to Rita Marley, Bob was monitored by the CIA and, in SA, as the apartheid regime feared, Marley’s songs provided jet fuel that legitimated and energised rebellion.

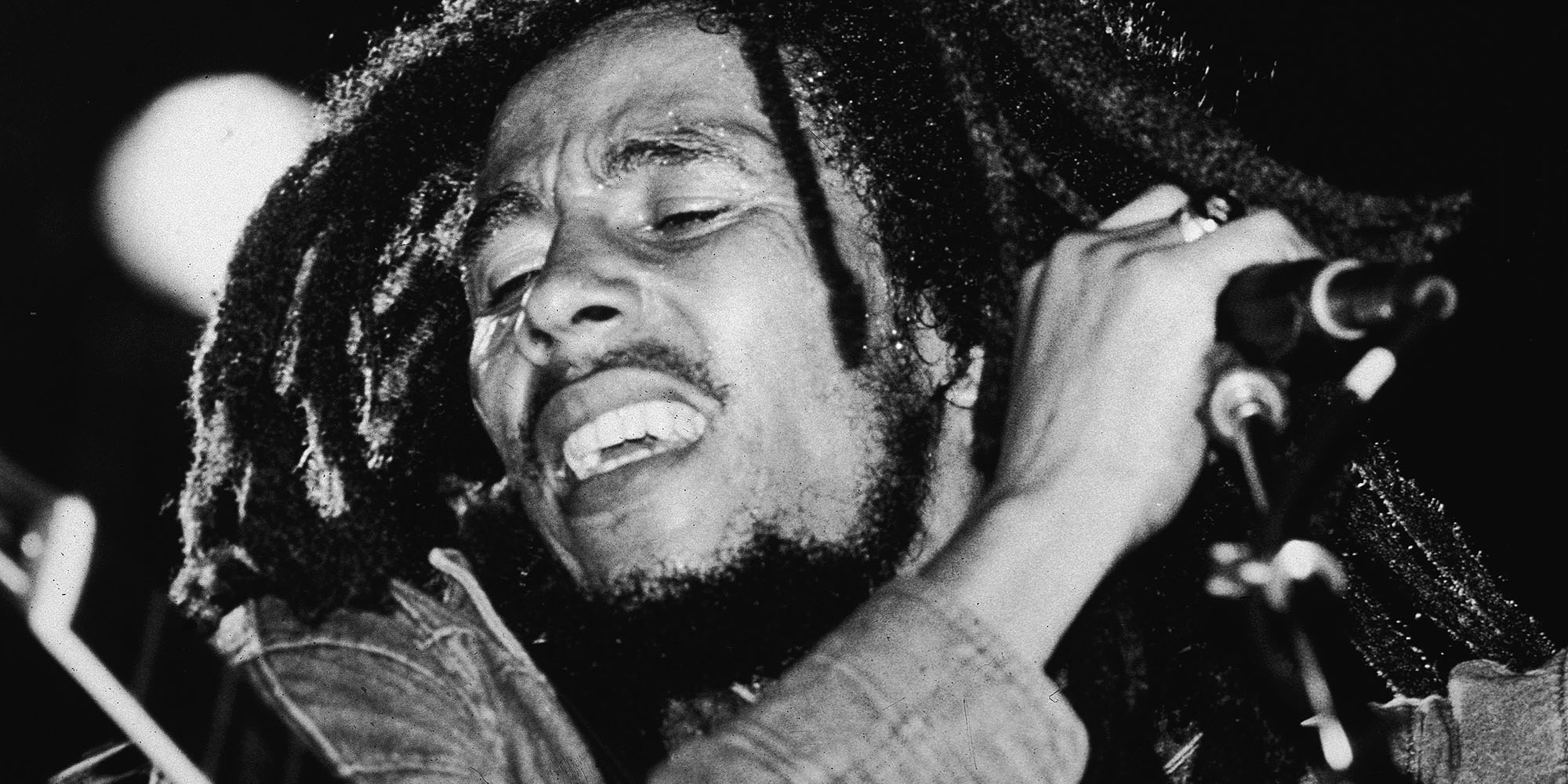

Jamaican reggae musician Bob Marley (1945 – 1981) performs on stage, a microphone in his hand, late 1970s. (Photo: Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

Talking about a revolution

Marley lived his principles of advancing non-racialism in the struggle for all human rights, while putting black dignity and oppression as the front of the agenda.

As we do today, Marley dreamt of a united Africa: “How good and how pleasant it would be, before God and man to see, the unification of all Africans.” (Africa Unite!)

In 1978 he was awarded the first Third World Peace Gold Medal by “the peoples of West Africa”. Yet tragically a cancer – whose existence he mistakenly believed could be overcome by faith alone – meant he did not live to witness the waves of protests that led to Namibian independence in 1989, swept away apartheid in 1994 and ended kleptocratic puppet regimes such as those of Hastings Banda in Malawi and Mobutu Sese Seko in then Zaire.

Marley was, however, alive to celebrate Zimbabwean independence in April 1980. He was the headline performer at the independence celebrations in (then) Salisbury.

He must have felt a sense of optimism – although the tear gas used to quell ordinary Zimbabweans who were trying to attend the concert was perhaps a harbinger of oppressions to come Bob would have preferred not to acknowledge.

He sang of Africa uniting and heralded that after the independence of Zimbabwe there should be “no more internal power struggles/ we’ve come together to overcome our little troubles”.

So, had he been alive, he would probably have wanted similarly to memorialise the inauguration of the African Union in 2002. But, just as with Zimbabwe, the AU has proved to be a union of governments, not of peoples. Across Africa the dreams of freedom were despoiled and then strangled in every country, including our own, by corrupt elites.

Colonialism gave way to post-colonialism, which gave way to neocolonialism; imperialism gave way to neoliberalism. Today independent states struggle to assert their sovereignty and to fulfil human rights that are now promised in their constitutions, succumbing meekly to the ratings agencies, the IMF and trading “agreements” – usually in return for 30 pieces of silver. The elites are rich, but people are still poor: “Them belly full, but we hungry. A hungry man, is an angry man!”

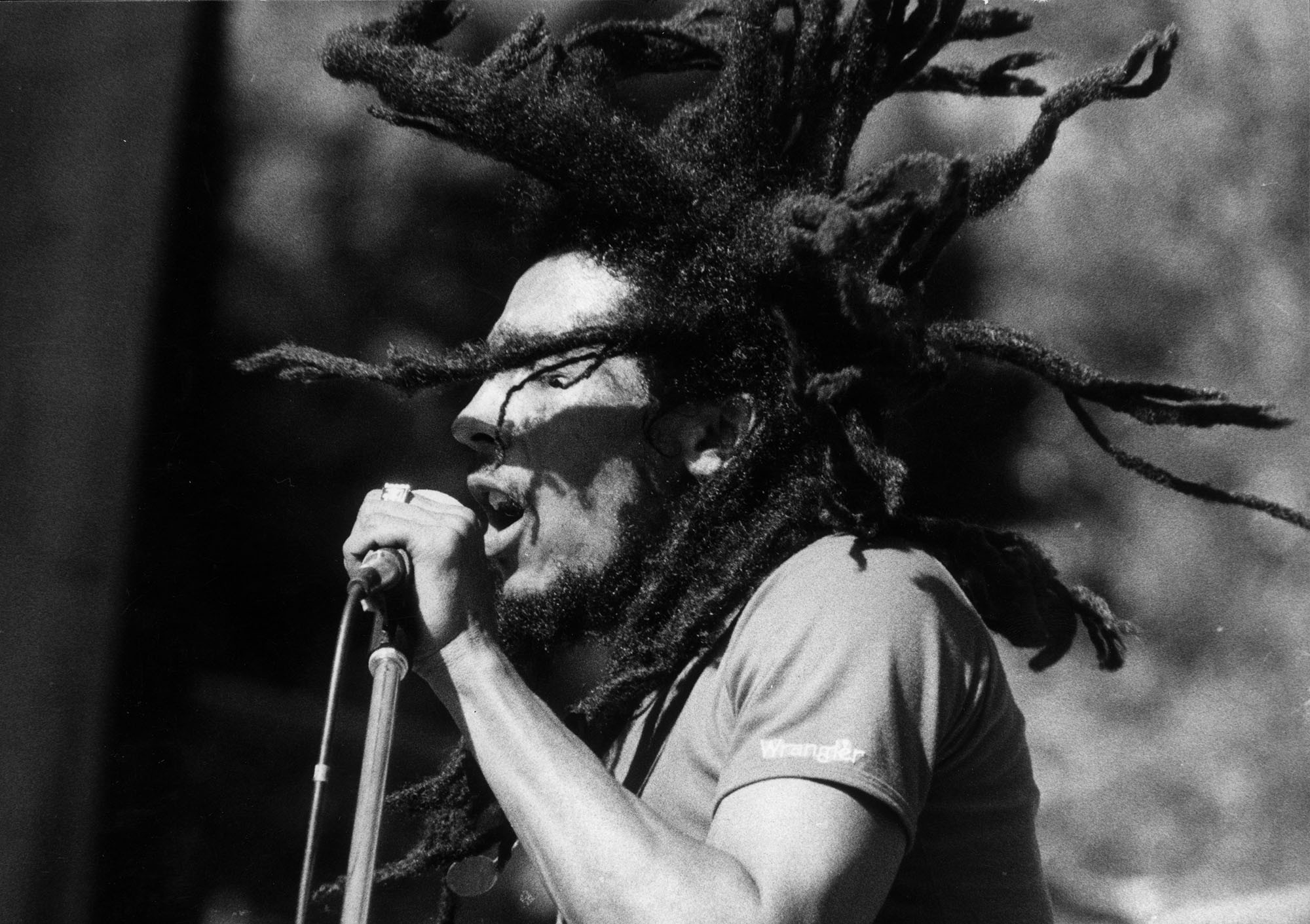

Jamaican reggae star Bob Marley (1945 – 1981), circa 1980. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Chase the crazy baldheads

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s the USA had fought proxy wars throughout the Caribbean and Latin America, including in Jamaica. Marley wasn’t scared. In Rat Race (a song on his 1976 album Rastaman Vibration) he defiantly proclaimed that “Rasta don’t work for no CIA.” Late in 1976, political gangsters, proxies of the CIA, would try to take him out, an assassination attempt he recorded in his song Ambush in the Night. Nonetheless, two days after being shot he would still sing at the Free Jamaica Peace Concert.

He derided and mocked the big men and the shadowy imperialists as “baldheads”. In the 1970s anti-colonial struggles were raging all over Africa and Latin America and Marley sensed that these uprisings had the baldheads on the run; he was wise to their tricks, spotted their stooges and sang exultantly that “we’re going to chase those crazy baldheads out of town”.

Here comes the con-man

Coming with his con-plan

We won’t take no bribe

We’ve got to stay alive. (Watch a live performance of Crazy Baldhead here)

Yet, when Marley died, in South Africa the crazy baldhead PW Botha was alive and well; the Soweto uprising was still fresh in his memory and, knowing it was in trouble, the National Party was embarking on a new strategy that combined brutal repression and murder with con-plans.

Marley was an Africanist and an internationalist. In Top Ranking he sang, “they don’t want to see us unite … all they want us to do is keep on fussing and fighting.” Yet when Marley died while the Berlin Wall still divided Germany and the world was still divided between the capitalist West and the Stalinist East.

When Marley died “Communist” China had not yet made its turn to capitalism, nor shot and bulldozed protesting students in Tiananmen square in 1989.

When Marley died capitalist economies were in crisis and neoliberalism was in its infancy, a wet dream of Milton Friedman and the Chicago boys. In 1977, after the attempt on his life, Marley had spent several months in exile in London, England. There he had seen the rising discontent of black and white youth and the working class. Before Marley, Rastas in Jamaica were a stigmatized and marginalized group, so Marley could and did empathise with the punk rock movement, what one national newspaper called the “foul mouth yobs”, who he endorsed in his song, Punky Reggae Party.

Then as now, punk and reggae found a natural alliance, an impolite fuck you to the status quo, young people opting to try and “free the people with music”.

Finally, consider that When Marley died when there was no internet, or e-mail or cellphones; no Twitter, Amazon, Facebook or Google. His songs and the feelings they conveyed travelled by word of mouth, by radio, on vinyl records – yet they still reached from Trench Town to every corner of the world. Each new album, and there were eight in the 1970s, had carefully conceived covers, each one a work of rock-art, becoming as much a part of an album’s identity and feeling as the songs within.

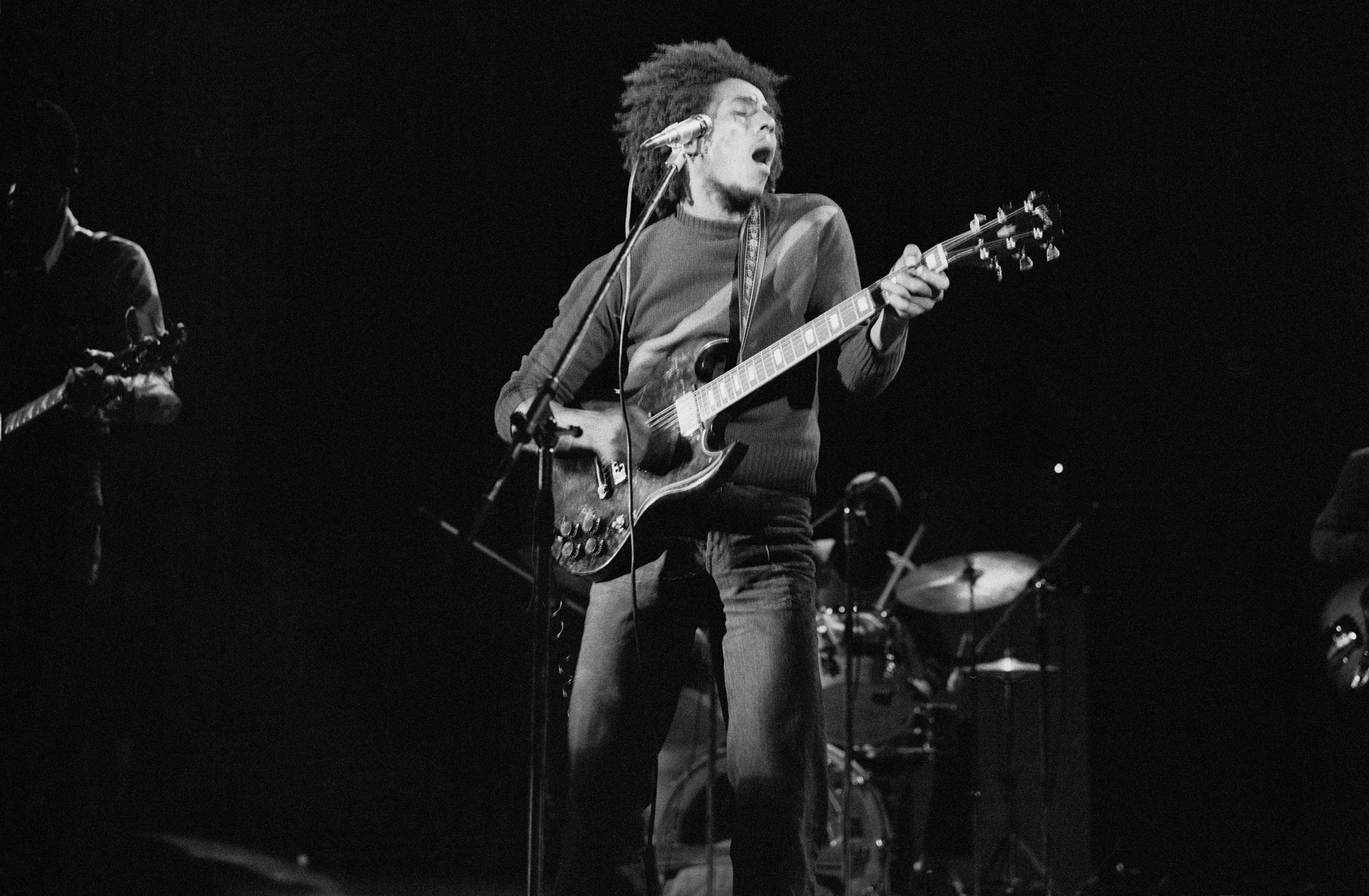

Bob Marley in concert. (Photo: Gary Merrin/Keystone/Getty Images)

Not all that glitters is gold

But despite all the “progress”, paradoxically, on his 75th birthday the world Marley railed against in the 1970s looks very similar to the world we live in today.

If you scratch beneath the glitter of modern technologies – look past your satellite dishes and cell phones, learn to emancipate yourself from new forms of mental slavery – in reality the patterns and systems of injustice that Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and others protested have not changed fundamentally.

Racism is rife, xenophobia has become a badge of honour for populists; and although capitalism escaped the economic crisis Marley witnessed in the late 1970s London, it has done so by birthing nineteenth century levels of inequality. The lament:

They make their world so hard

Every day the people are dying (One Drop)

… has not become obsolete.

There is still ‘so much trouble in the world’; there is still a need to “stand up for your rights” in today’s pivotal struggles around for social justice, gender equality, against the climate crisis and war.

The youth of today are paying the price for the failed revolutions of the past. We must celebrate Marley’s 75th birthday at a time when once more big racist men – Trump, Putin, Bolsanero, Orban, Johnson, Xi Jinping – appear to have consolidated and entrenched their power across the world.

But they are not without challenge, because “we’ve got something they can never take away – it’s the fire”.

Thinking about what Bob Marley meant to me personally, I realise that in the 1970s and 1980s Bob Marley helped a generation of young white people who were at odds with their world to get out of their skins. It motivated us to take a stand against racism and colonialism. I bought my first Bob Marley LP in the late 1979s, aged 15. The second song on Natty Dread is the studio version of No Woman No Cry, which at that time – Bob Marley-for-beginners – was on the way to becoming an anthem for millions of youth worldwide. Like others of Marley’s more commercially successful pop songs, Could You be Loved and One Love, it was played in dance halls, parties and discos.

But as so often happens with music, a song can be an entrée that opens up much deeper social and political questions. I discovered that the rest of the songs on Natty Dread were far more trenchant and uncompromising; just the injection of rebel music I needed, a “vocab” for my own political awakening.

Today, Marley-isms from Natty Dread are as firmly embedded in my world view as they were then:

“It takes a revolution to make a solution”

“Never let a politician, grant you a favour

He will always want to control you forever” (Revolution)

“Why can’t we roam, this open country

Oh, why can’t we be what we want to be,

We want to be free!” (Rebel Music, 3 O’clock Road Block)

“’cause I feel like bombing a church

Now that I know that the preacher is lying.

So who’s going to stay at home

While the freedom fighters are fighting?” (Talkin’ Blues)

These songs – along with others by Peter Tosh, the Sex Pistols and the Clash – helped politicise a generation. They wed me to all genres of rebel music.

But it was not just the lyrics. There was something extra about Marley’s spirit and swagger. He was the extraordinary “ordinary” that we all hope to find within ourselves; a lover of football, loyal and generous to his community, given to laughter, love, naughty, unpretentious. Driven but not dogmatic; passionate but not self-righteous, political but not didactic; religious but not rigid.

If only the socialists had learnt a little from the Rastafarians!

Happy birthday Bob Marley

These are reasons why I can remember the day Marley died in 1981. I was 17, coming out of my school’s morning assembly when the news of his death was reported on the radio. I sensed something had shifted in the world. Later, Marley’s stature was confirmed when I saw news footage of the crowds who, for 72 miles, lined the route from Kingston to his birth and burial place in the village of Nine Miles in the parish of St Anne, high in the mountains. A state funeral was ordered by then Prime Minister and Prime crazy baldhead Edward Seaga who continued his quest to try and appropriate some of Bob’s power even in death; it was a send-off with riddim and the waft of ganja, befitting a pope or a freedom fighter. Unusual for a musician and a Rasta.

These are reasons why, as he turns 75, Marley’s spirit remains embedded in our souls. His songs are as on-point and mobilising as they were in the 1970s and 1980s. His years too were a time of uprising, a revolt against the “shitstem”, a Vampire that is “sucking the blood of the suffarahs”, a youth rebellion that is once more on the rise from Zimbabwe to Hong Kong to India to the United States.

His and others’ struggle for black dignity, human rights and social justice has advanced, but it is unfinished.

It is now carried forward by movements like Black Lives Matter, #FeesMustFall, #MeToo, #FridaysForFuture, the Sunrise Movement.

And in South Africa, Bob still lives among us. Jo Menell, a South African who made the first documentary film about Marley, told me recently how “The other day in Mfuleni, a godforsaken township, I saw, beautifully painted on a white wall “Them belly-full, me hungry, a hungry man is an angry man…..”

Nonetheless, Bob’s lyrics would benefit by being updated by musicians who can speak to the depredations of today. In the words of Fred Khumalo:

“We need new reggae songs about Trumpism. About world inequality. About the Guptas. About kids drowning in pit latrines because the South African government can’t provide them with proper toilets.

“Keep the spear burning, Jahman! Let’s chant dese reggae ridims until the walls of Jericho fall.

“Let’s chant down the walls of dis here Babylon!”

Marley can still lift us up on dark days, give us energy with his rhythm. Bob Marley may have grown old, but his songs have not. Bob Marley may be resting, but I doubt in peace. Bob Marley laid a foundation for rebel music, his words speak to eternal and universal issues of injustice. In Equal Rights Peter Tosh famously sang: “I don’t want no peace/I need equal rights, and justice.”

Aluta continua! MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider