SURVEILLANCE

How China’s persecuted people are paying the price for Joburg’s sense of security

On 8 July 2019, 22 member states of the United Nations Human Rights Council petitioned China to end the ‘arbitrary’, ‘large-scale’ detention and ‘widespread surveillance’ of its religious communities. But the very surveillance tech tried and tested on China’s Muslims, Christians, Buddhists and Catholics is now being deployed en masse throughout Joburg by SA company Vumacam – for safety’s sake. And while a hot debate rages over South Africans’ privacy, persecuted people halfway around the world are truly paying the price for this technology.

A world where the traffic police can suddenly stop your car and inspect your cellphone without a warrant. A place where you can be sent to a detention camp for having WhatsApp installed on it. A town where you can be classified as “suspicious” if you use your back door too often, don’t socialise with your neighbours often enough, or use more electricity than usual. Here, any number of seemingly ordinary behaviours can land you on the police’s radar, sparking an investigation into your personal life, often with dire consequences.

This is the Chinese province of Xinjiang, aka the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. China’s last census (in 2010) counted 22 million people here, with around 45% being Turkic Muslims. Also known as Uyghur Muslims, they are subjected to the extreme crackdown on religious groups that the ruling Chinese Communist Party has instituted within the region since 2016.

Xinjiang Province, home to more than 10 million Uyghur Muslims. One million Uyghurs are reportedly being kept in detention camps without recourse. (Source: Wikipedia)

In April 2019, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) released its annual report, detailing the extent of the oppression. Under the banner of fighting terrorism, the People’s Republic of China government launched its “strike hard” campaign in 2014. It’s a deliberate, systematic effort to assimilate all religious people into the mainstream Chinese population by attempting to wipe out religious practices and their accompanying cultural and linguistic heritages.

Through the new “Regulations on Religious Affairs” (implemented in February 2018), China has outlawed religious teaching not authorised by the government, and faith-based groups must declare all their online activities. The most heavily persecuted are the Tibetan Buddhists and Uyghur Muslims, but the state has shut down hundreds of Protestant churches too. Close to 1,000 Falun Gong practitioners have been arrested this past year for handing out literature or simply practising their faith (which largely entails breathing exercises and meditation). Catholics, who practice their religion in secret, continue to be oppressed, despite the Vatican’s agreement with the state that Chinese authorities would now have a say in the appointment of bishops in China.

Three key aspects of the government’s strategy to keep religious people in check are surveillance cameras, a massive law enforcement contingent, and detention centres (aka ‘re-education’ camps). Cameras monitor schools, streets, restaurants and places of religious worship, and police can confiscate your mobile phone and download its contents without a warrant.

At best, a person caught in the police’s dragnet faces questioning and a few hours’ detention at one of Xinjiang’s many security checkpoints.

At worst, he or she ends up in a “re-education” camp. In 2018, the United Nations said that it had credible information that more than a million people were being kept in such detention centres in Xinjiang. USCIRF, referring to the centres as “concentration camps”, estimates the number of detainees at between 800,000 and 2 million, and say children whose parents are detained are placed in orphanages.

Government surveillance makes it impossible to contact family members for fear of further persecution. Those who have made it out of the camps tell of being subjected to the teachings of the ruling Chinese Communist Party doctrine for 12 hours a day, abhorrent living conditions, and even the deaths of people in custody.

Apart from indefinite internment without legal recourse, punishments include being forbidden to leave the country, your neighbourhood – or even your house. This is according to Human Rights Watch 2019 report titled “China’s Algorithms of Repression”. In it, HRW illustrates how Chinese authorities use information to keep a tight grip on Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang. Apart from interviewing numerous former Xinjiang residents about their experiences there, HRW reverse-engineered the so-called “Integrated Joint Operations Platform” (IJOP) – software that the Chinese authorities use to collect, process, and share citizens’ data. This revealed the extent of the Chinese state’s use of private information to control its people.

You don’t have to be part of an extremist group to be under surveillance: everybody’s data is collected. The IJOP is used, for example, to log people’s movements (through their phones’ location data), electricity usage, petrol consumption, and personal associations. Having a relationship with someone who, for instance, just got a new phone number, means you are flagged as “suspicious”. Even details such as precise physical height and vehicle colour are collected.

Data stored on the app is used to formulate action plans for police, which usually entails investigating “suspicious”’ people. You are labelled as “suspicious” for dozens of reasons: donating to mosques, using a phone not registered in your name, leaving your designated locale without police permission, or being related to someone blacklisted for being “suspicious”.

The technology used in Xinjiang’s surveillance network has made its way to the streets of Joburg’s most affluent suburbs. In 2019, local company Vumacam is busy installing 15,000 high-definition surveillance cameras throughout Johannesburg to prevent crime. Vumacam’s camera supplier, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, is also a major supplier to the Chinese government in Xinjiang.

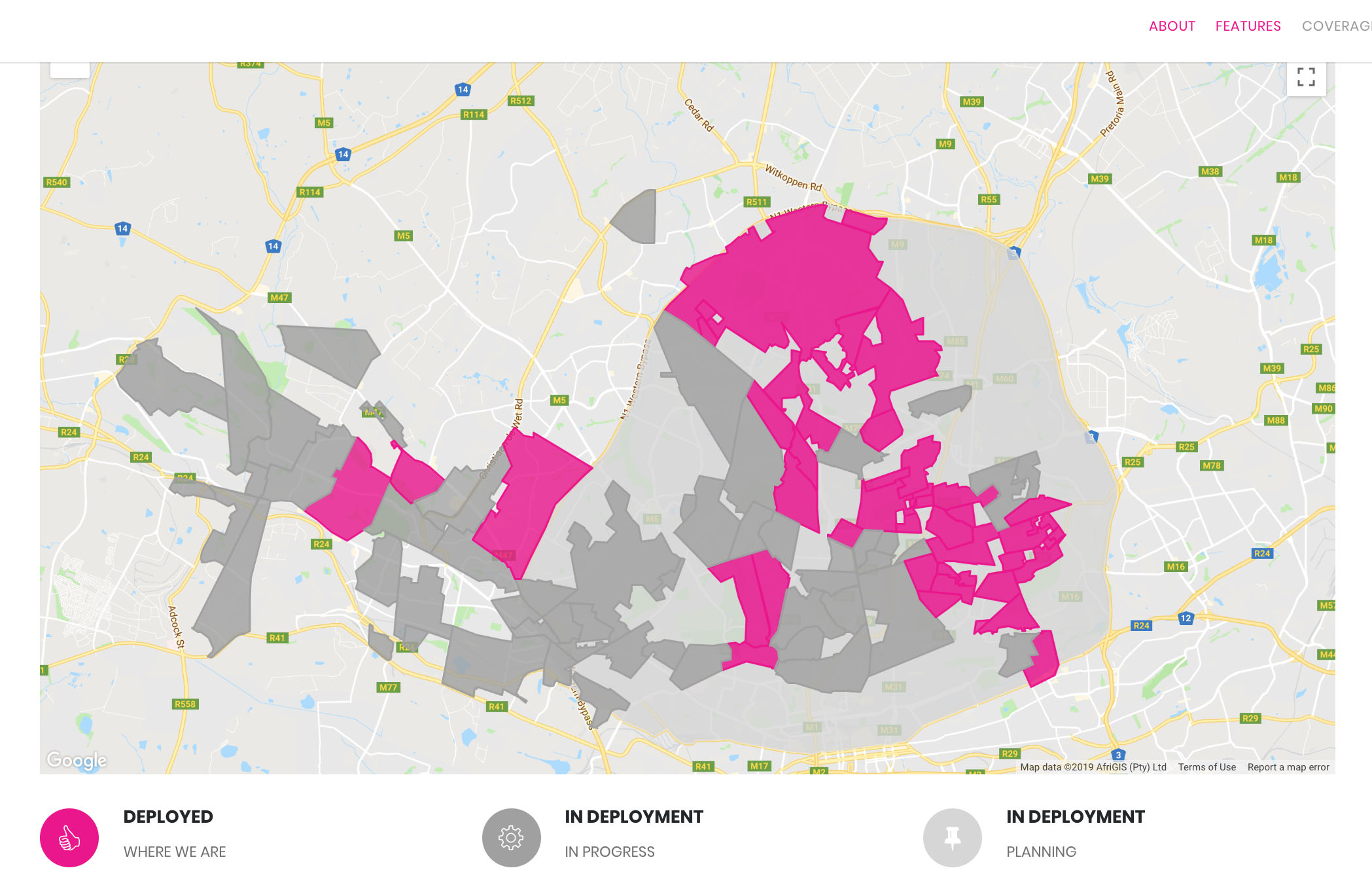

Vumacam’s grand plan: The SA company aims to have 15,000 high-definition Chinese-made surveillance cameras installed throughout Joburg this year. (Source: Vumacam)

According to the Associated Press Hikvision won five contracts in Xinjiang in 2017 to the value of ¥1.85-billion (Yuan) – about R3.7-billion. One of the contracts, worth ¥309-million (about R620-million), was for a project in the rural county of Moyu. AFP also obtained tender documents indicating that about 35 000 surveillance cameras would be deployed to cover schools, offices, and roads in the county. Some 967 mosques were identified for camera surveillance installations to make sure that imams adhere to government-approved teachings.

Another investigation by surveillance product evaluator group IPVM found that Hikvision was allocated nearly $300-million worth of government tenders for work in Xinjiang in 2017.

One of these contracts – to the value of $53-million – was for a mass facial recognition camera network in Xinjiang’s Pishan County. Through investigating tender documents, IPVM confirmed that part of the Pishan County contract includes installing a surveillance system in a re-education camp there. Facial recognition software is used to analyse video footage to identify specific features of a subject’s face.

It has emerged that identifying “ethnic minorities” is one of the reasons facial recognition cameras are being used in China. A 2018 marketing video from Hikvision illustrates the blatant racial discrimination of the software. But it also reveals serious shortcomings. In one image, a person who is clearly wearing glasses is identified as wearing no glasses. The software says the person is male, when in fact the gender is not clear. IPVM reported on the issue and, shortly after the mainstream media picked up that report, Hikvision removed the video from their website. IPVM, however, had retained the footage. You can view it here.

Hikvision claims to have developed facial recognition software that can identify ethnic minorities. (Source: Hikvision/IPVM)

Although Hikvision is selling facial recognition technology, it still has a long way to go, according to two independent security consultants to whom Daily Maverick spoke on condition of anonymity. One expert explained that it requires three-dimensional models of every citizen’s face before the software could really work.

Such databases don’t yet exist. But China is working on it.

Last year a report by Al Jazeera documented how Chinese authorities in Xinjiang monitored Uyghur people. One man who fled to the United States with his family to seek asylum told the agency how both he and his wife were summoned to a police station where authorities drew their blood, took voice samples, and photographed their faces from multiple angles. Police also documented facial movements and multiple expressions. This is the type of data required to build a database necessary for facial recognition software.

Hikvision is also working with Vumacam to develop products tailor-made for the South African company’s surveillance needs. In a press conference in February this year, Vumacam’s managing director Ashleigh Parry described the company’s relationship with the Chinese government-controlled company as follows:

“Our friendship, our relationship is a very close one; they actually develop stuff for us. We’ve got a new camera that they are creating for us specifically that is a dual-lens camera, so we’ve got very close relationships with them.”

And Hikvision has another close relationship – with China’s ruling Communist Party. Surveillance of civilian spaces is big business in China and bolstered by the state. The government owns a 42% stake in Hikvision through the 100% state-owned China Electronics Technology Group Corporation – aka China Electronics.

But the relationships don’t end there.

Incidentally China Electronics, a military contractor, also connects Hikvision to the IJOP project. China Electronics owns Xinjiang Yuanjian Communication Technology – the company that developed the IJOP application. In addition, a job advert for that company (discovered by IPVM) stated that it “co-operates with China Electronics Technology Group Corporation and Hangzhou Hikvision Technology Co., Ltd. to be responsible for the construction, implementation and operation and maintenance” of the IJOP project.

These relationships illustrate a growing trend: surveillance footage is increasingly being utilised with other forms of information and communications technology to manage people.

Vumacam also hopes that its network will eventually be more than just cameras.

The company stated earlier this year that it sees the “need for cities to become smarter and more efficient. We hope that we can be a part of that exciting future. These smart-city initiatives could possibly tackle congestion, energy efficiency and emergency care response times, to name a few.”

Smart cities refer to urban areas where data from internet-linked devices (for example, surveillance cameras, your home’s electricity and water metres, traffic lights, etc) assist in better managing the city.

Incidentally, smart city development is high on the Chinese Communist Party’s agenda. This is according to the website of China’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC), the government body ultimately overseeing China’s social and economic development. (Hikvision and its parent company China Electronics are also subject to SASAC’s supervision.)

One of the cities destined to become smart, is the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. The ultimate aim of this, say Chinese authorities, is a “new, healthy and happy” city.

But the people in Tibet, around 80% of who are Buddhists, are anything but. Lhasa is no exception. Between 2011 and 2018, a total of 153 people have set themselves on fire in protest against government oppression. Two did so in Lhasa at the Jokhang Temple, considered the holiest of Buddhist sites in Tibet. Tibetan monks, nuns and ordinary citizens have been among the protestors, and 131 of them have died. The remainder have been disabled, severely injured, or gone missing.

The figures are the latest to be released by the Central Tibetan Administration. Situated in India, it is the formal Tibetan parliament-in-exile. The Dalai Lama established it after he escaped from Tibet in 1959 following the Tibetan uprising (which started in Lhasa). At the time, what remained of the Tibetan government was formally disbanded. This brought to a climax the so-called “incorporation” of Tibet into China, a process set in motion in 1951 by Mao Zedong’s Communist Party (although Mao’s forces had already invaded Tibet in 1950).

Since then, Tibet has become known as the Tibet Autonomous Region, despite its struggle to gain recognition of independence internationally. The Central Tibetan Administration considers China’s presence in Tibet to be a military occupation.

Persecution of Buddhist monks and nuns is known to continue, although it is much harder to obtain information from Tibet than Xinjiang. Tibet is off-limits to foreign reporters, and the Chinese government strictly controls the flow of information in and out of the country.

Free Tibet, an international campaign for Tibetans’ basic human rights, reported that 70 nuns were evicted from the religious community Yarchen Gar in Kardze, eastern Tibet, earlier this year. The women have reportedly been taken to detention camps, where they will be forced to undergo political re-education and give up their religious practices. A report by independent news agency Radio Free Asia stated that as many as 3,500 monks and nuns were evicted from the Yachen Gar Tibetan Buddhist Center located in Tibet’s Kardze prefecture in May.

A Yachen Gar settlement in Tibet’s Kardze prefecture being demolished in August 2017. (Source: Radio Free Asia)

Kardze was the scene of multiple anti-government protests in 2011 by Tibetan Buddhists.

But that same year, security was substantially tightened when Chinese Communist Party member and former soldier Chen Quanguo became the party secretary of the TAR. Incidentally, China Electronics also started to develop Lhasa as a smart city in 2011.

As the highest-ranked official in the region, Chen spent five years building a security system that hinged on surveillance and visible policing – known among Chinese officials as “grid-style social management”. Cities or towns are physically divided into zones, and high-definition, internet-based surveillance cameras are linked to police databases and employed to keep tabs on citizens.

Manpower is needed to act on all this data, and at least 700 “convenience police centres” were established in Tibetan urban areas between 2011 and 2016. This is according to a 2017 research report by the global research and analysis group, the Jamestown Foundation. Lhasa itself, according to China’s Ministry of Public Security, had 161 of these stations by August 2012, spaced 500m apart. The Jamestown Foundation estimates that over 12,000 policing jobs were advertised in the TAR between 2011 and 2016. In 2016, Chen was appointed as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region party secretary and has since replicated his work in Tibet in Xinjiang.

Hikvision has been accused of aiding Chen to turn Tibet into a surveillance state. The International Campaign for Tibet stated in December last year that Hikvision technology was used in Tibet “as part of the development of one of the most dystopian and intrusive police and security states in the world”.

One of the earliest known cases of Hikvision’s presence in Tibet was its supply of surveillance equipment for the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, a 1,956km stretch of train tracks connecting Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province, to Lhasa. It was officially opened in 2006.

In May 2017 Xiong Qunli, chairman of China Electronics and a Communist Party representative, headed a delegation to Tibet to sign a “Strategic Co-operation Framework Agreement” with the Lhasa Municipal Government. The agreement would serve as a platform for Lhasa to “establish a benchmark” for and “accelerate” the construction of new smart cities in the TAR. During this Tibetan trip, Xiong met with a number of technology companies, including Hikvision, which has offices in Lhasa.

Due to its association with human rights abuses, there has been increased pressure for Western governments to cut their support for Hikvision.

In February 2019, UK Member of Parliament Karen Lee called on the UK government to speak out about Hikvision’s involvement in human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Tibet. Hikvision is the UK’s leading surveillance equipment provider.

Reacting to the Xinjiang crisis, the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the US House of Representatives wrote letters calling on President Donald Trump’s administration to impose sanctions under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act. The Act gives the US president the power to place visa bans and sanctions on people and companies who commit human rights violations anywhere in the world. Both Democrats and Republicans signed the letters in August 2018 and February 2019. Hikvision and Chen are specifically identified in the correspondence.

In May, Trump’s administration reportedly considered placing limits on Hikvision’s purchases of US technology as retaliation against religious oppression in Xinjiang. However, nothing came of this.

No sanctions have as yet been imposed on the company due to these human rights concerns, and it continues to grow worldwide – along with global surveillance networks.

Hikvision is the world’s largest surveillance equipment producer in terms of revenue. Their latest annual report shows a total revenue of around R107-billion in 2018.

Hikvision is also growing in SA, although the extent thereof is difficult to establish. Neither Vumacam nor Hikvision provided any of the specific financial details requested by Daily Maverick, but there is some information known to the public.

Vumacam has formally stated that they plan to erect 15,000 cameras throughout Joburg in 2019, and that it currently charges residents’ associations using its surveillance services R730 per camera per month. Given that the rental terms remain constant, the company is looking to gross about R131-million a year from the Johannesburg area once all the cameras are installed. Expenses deducted from this would include items like maintenance and operations costs. Vumacam said it would cost about R500-million to install the entire Joburg network. It also wants to establish a network in Cape Town.

Daily Maverick asked Vumacam why it chose to partner with Hikvision despite the company’s record of involvement in human rights abuses. Vumacam did not directly answer questions related to human rights issues, despite Daily Maverick requesting a specific response on three separate occasions over the course of a week.

Hikvision’s response to our questions is as follows:

“Hikvision takes human rights compliance very seriously and has engaged with the U.S. government regarding all of their concerns since last October. In light of them, it has already retained human rights expert and former US Ambassador Pierre-Richard Prosper to advise the company regarding human rights compliance.

“Over the past year, there have been numerous reports about ways that video surveillance products have been involved in human rights violations. We read every report seriously and are listening to voices from outside the Company. We are taking a hard look at our products and business. As part of this process, we have recently commissioned an internal review of our operations by the U.S. law firm, Arent Fox LLP, mandating it to look into relevant transactions so the Company can enhance its screening standards to better protect human rights. Arent Fox will also help us improve the policies that will help ensure human rights compliance going forward. As part of this effort, a high-level team from Arent Fox has already travelled to China twice.

“Hikvision respects the human rights as set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in commercial practice. Meanwhile, we will incorporate these provisions into our business procedures and policies in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights Framework to enhance the value of our business activities.

“In 2018, the Company has appointed the Chief Compliance Officer, responsible for promoting the compliance construction covering areas of human rights protection, data security and privacy protection as well as social responsibility, etc. We have a professional legal team conducting investigating, recognition and tracking the laws and regulations applicable to global operation of the Company and carrying out the construction of human rights compliance with the situation of the company.” DM

Heidi Swart is an investigative journalist who reports on surveillance and data privacy issues.

This story was commissioned by the Media Policy and Democracy Project, an initiative of the University of Johannesburg’s department of journalism, film and TV and Unisa’s department of communication science.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider