The portfolio offers a wide-ranging visual history of the internecine conflicts and violent strife that engulfed large parts of South Africa in the 1990s. This followed the unbanning of 33 political parties and release of political prisoners, in the protracted lead-up to non-racial elections in 1994. The photographs bear unflinching witness to the painful becoming of a nation. Many works in the CCAC speak to the political and social strife preceding our country’s transition to a constitutional democracy.

Collateral Damage

Southern Transvaal

Soccer Grave

Ratanda, 1993

A football team buries their team-mate who was killed in crossfire between ANC and IFP fighters while playing soccer in Heidelberg’s

Ratanda Township. The political rivalry in Ratanda combined with politically aligned unions vying for jobs in local meat-processing

factories resulted in several people being killed in confrontations. Photo Greg Marinovich

Storm

Duduza, 1993

A group of African National Congress supporting Xhosa men wait out a summer storm during a battle with Inkatha Freedom Party supporters. Before the storm, the wide boulevard had been filled with tens of thousands of people wanting to chase the IFP supporters out of their hostel stronghold – only these men stayed through the rain. Photo Greg Marinovich

It feels distinctly odd to write the phrase Southern Transvaal; it makes me feel several decades older than I am. It is an area one mostly drives past on the highway, but in the periods of political uprisings in the 1980s and 1990s, the small black townships. These places served as dormitory towns to the gold and coal mines and associated industries and thus I would find myself, mostly in the company of Joao Silva, following one of those South African atlases to find my way to townships by the name of Ratanda or Duduza. These remote settlements were hidden from the sensitive gaze of the white town, as per apartheid spatial and social engineering.

In Ratanda, the broader political conflict between the African National Congress and the Inkatha Freedom party had spread to the unions that aligned with these parties. The unions represented meat processing workers of Enterprise and other factories where they made bacon, polony and other very pink meat-like stuff. While the politics inflamed things, it was really about getting rid of opposing unions to get your friends, cousins, brothers into the jobs. That conflict spread from the factory the residential areas of Ratanda and in one terrible incident a shoot-out occurred while a soccer game was taking place and players were gunned down on the rough dirt pitch; others were also killed. Those funerals took place with a soccer team in their uniforms bidding their young friend goodbye; alongside them, a Zion Christian Church member was buried too. The gravedigger waited atop a mound of orange earth to close the hole and move on.

Monsters of History

The Vaal

Aaron

Boipatong, 1992

On a winter’s night in the Vaal, 45 people were killed when a large group of men rampaged through Boipatong Township. Klaas Mathope and many other survivors maintained that it had not been just Zulus who had attacked them, but white policemen too. When Klaas had run from the armed group, known

in Zulu as an impi, he had heard a white man’s voice saying in Afrikaans: ‘Zulu, catch him.’ Several shots were fired at him but he managed to hide in some bushes. From his hiding place, he listened to the attackers killing people. When it was all over, he returned home to find his wife lying on the ground with her intestines hanging out – she had been stabbed and shot repeatedly. She was near death, but told him to leave her and to go to find their son Aaron instead. Klaas left his mortally wounded wife and went to look for the infant, but his child Aaron, nine months old, was already dead, murdered in the attack. Photo Greg Marinovich

Shooting

Boipatong, 1992

South African President and National Party leader, FW de Klerk, tried to visit the scene of the Boipatong massacre four days after it occurred. People greeted him with signs accusing him of being a killer. De Klerk smiled and waved from behind the bullet-proofed glass. Despite a massive police presence, the enraged residents cursed and stoned his limousine. After he left, police shot and killed a man during a confrontation I did not witness. By the time I got to the open field, a crowd gathered wanting to identify the body but a ring of riot unit policemen refused to allow them near the body. The angriest and bravest among the residents stood face to face with the heavily armed white policemen, screaming insults and spitting at them. Then the inevitable happened – the cops opened fire at point-blank range. I had stupidly been on the wrong side but I somehow managed to get behind the police line and photographed them firing at the fleeing people. Several people were killed and many were injured. Photo Greg Marinovich

The southern part of the Witwatersrand is called the Vaal Triangle. The Vaal includes historically infamous townships like Sharpeville of the 1960 massacre that is now commemorated as Human Rights Day on 21 March. It is also home to the much larger Sebokeng township where a night vigil for African National Congress leader Chris Nangalembe was attacked and 38 mourners killed. That was January of 1991, not a day etched into our collective memory.

In the same neighbourhood, in the same year, 14 people were killed at a protest march. Later, sprawling informal settlements mushroomed into a place called Orange Farm, where even today the same struggles for economic equality, water, security and justice continue to be fought. But the Vaal is best known for the Boipatong massacre, where 45 people were hacked and shot to death in the night. The youngest was a nine-month-old baby boy called Aaron Mathope. At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Inkatha Youth leader Victor Mthembu explained why the child was killed – “You must remember that a snake gives birth to a snake.”

Celebration & Rage

Soweto and West Rand

Somersault

Soweto, 1993

African National Congress and Communist Party supporters scatter as police fire teargas and live rounds outside the Soweto soccer stadium where the funeral of ANC and CP leader Chris Hani was attended by hundreds of thousands of mourners on 19 April. Photo Greg Marinovich

The Riot Policeman

Bekkersdal, 1994

Riot Police help a colleague injured by a grenade during clashes between security forces, ANC and AZAPO supporters in the far West Rand township of Bekkersdal in February of 1994, two months before the first democratic elections. Photo Greg Marinovich

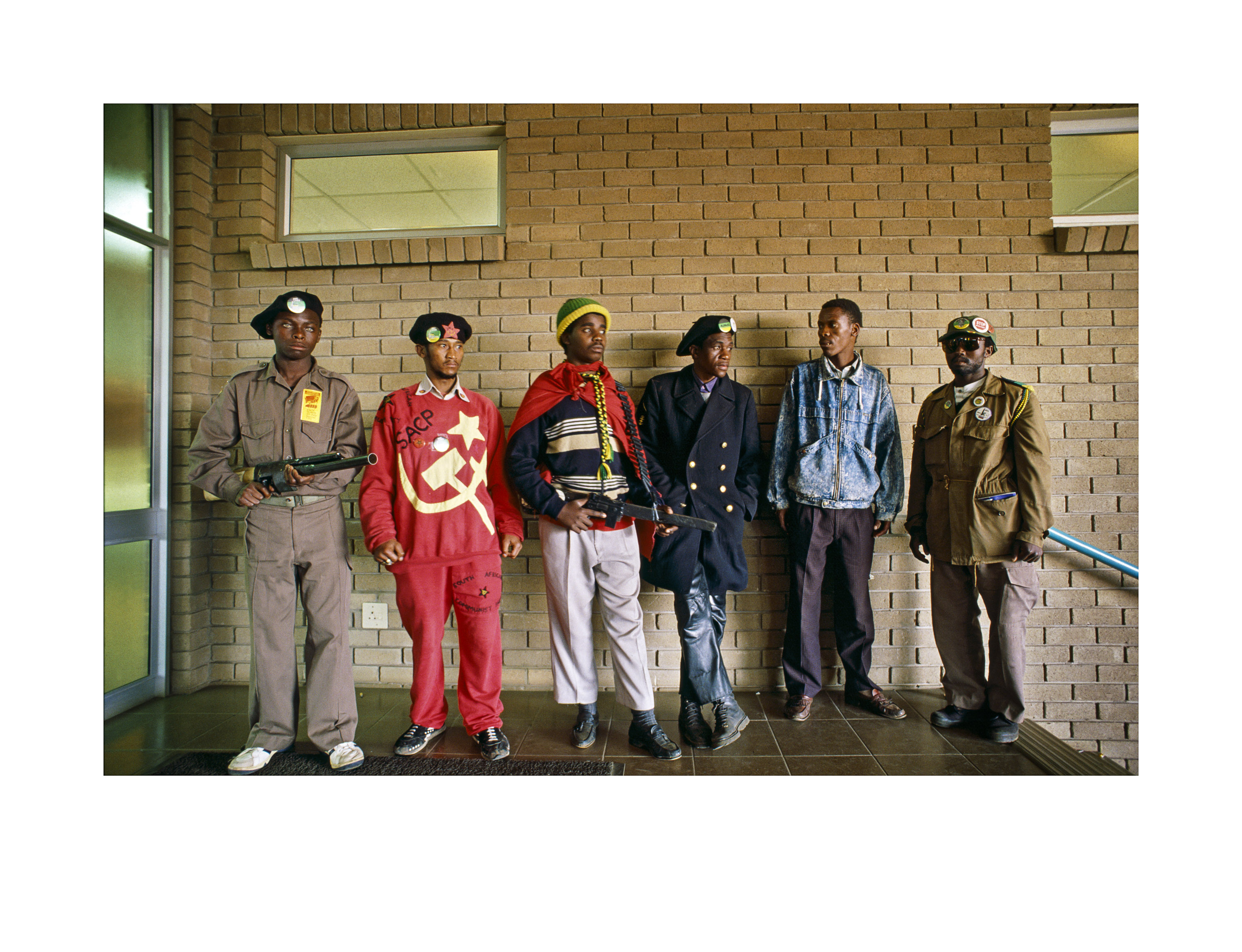

The Party

Soweto, 1990

Supporters of the South African Communist Party pose in various homemade Party apparels, at the football stadium outside Soweto, where its first public meeting was held after they had been banned for decades. Many of the participants were still nervous of being seen to be publicly supporting the Party. Photo Greg Marinovich

People used to say Soweto sneezes and the country falls ill and it is true that the intellectual and leadership capital – the names Mandela, Sisulu, Motlana, Petersen, among so many others were centred in this massive hilly city that was barely a municipality, legally speaking. When the South African Communist Party decided on a venue for its first public rally after being unbanned in 1990, they decided on Soweto’s Soccer City; what other places could hold the numbers and serve the largest black population? That was a joyous if nervy affair, but two years later when Chris Hani was assassinated in his driveway by white supremacists, his vigil was held in that same stadium with an entirely different mood as the country stood on the edge of disaster.

The Leopard Skin & the T-shirt

KwaZulu-Natal

Scar

Shobashobane, 1996

A young African National Congress supporter, who was shot through the face during the Christmas Day massacre in 1995, returns to his home which was torched when some 600 men attacked the area, killing 18 people and wounding many more. A lot of the bodies were mutilated for imuthi – traditional medicine, often inthelezi. Survivors said police raided the area the day before to search for weapons. Despite being repeatedly warned of an impending attack, the police were absent. This was a clear-cut case of the security forces assisting the IFP in their battle with the ANC. Photo Greg Marinovich

The Return #1

Sonkombo, 1994

A family carries home their belongings after months spent in a tented refugee camp for African National Congress supporting families from the Sonkombo area from which they had fled months earlier because of attacks by rival Inkatha Freedom Party supporters. Greg Marinovich

An Inkatha Freedom Party supporter runs back from the dividing line between political factions after emptying his AK-47 ammunition clip towards the homes of African National Congress supporters in Umlazi Township. Eight thousand IFP fighters received training in the Caprivi Strip from elements of the South African police and military. There are still arms caches buried across KwaZulu-Natal that have not yet been unearthed despite a massive one discovered and destroyed in 1999. Photo Greg Marinovich

The hills of Zululand had long been nourished with blood; the Hostel War that raged across the Reef in the 1990s was a more complicated rendition of the conflict that had torn across the Zulu heartland the decade before. Neighbour pitted against neighbour; father turned against brother as people had to choose between the conservative tribal homeland regime of Inkatha and the non-racial/non-tribally identifying ANC. It was never that clear cut, but many, many died.

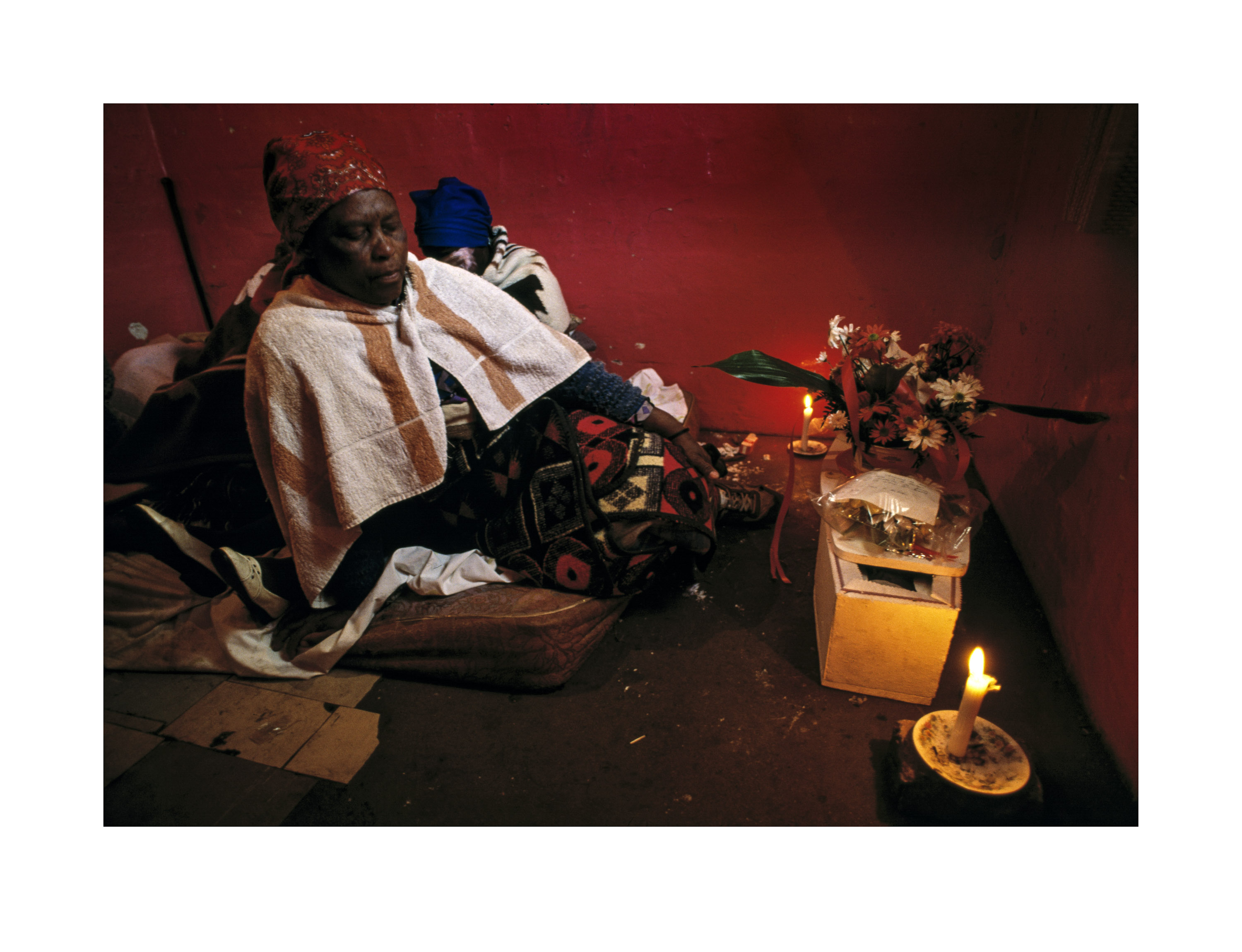

Comrades & Comtsotsies

Thokoza

Khalanyoni Hostel

Thokoza, 1990

African National Congress supporters push over a breeze-block wall, part of Khalanyoni hostel at the southern end of Khumalo Street. Khalanyoni hostel was overrun early in the war by ANC fighters, most of whom were Xhosa tribesmen from the adjacent Phola Park shantytown. These warriors were called ‘blanket men’ by the police as they wore their blankets to fight, hiding sticks, spears and guns under the heavy wool folds. They dismantled the buildings, brick by multi-coloured brick, and used them to rebuild their shacks that were destroyed in the fighting. From day to day, the shantytown transformed itself from a maze of drab corrugated iron into a bizarrely colourful place. The surviving Zulu hostel-dwellers from Khalanyoni hostel retreated to the hostels at the northern end of Khumalo Street. Photo Greg Marinovich

Smoking Hat

Thokoza, 1996

African National Congress supporting activists stand above a cap, still smoking from a point-blank range gunshot of a fellow Self Defence Unit comrade killed by Inkatha Freedom Party members while watching the FIFA football World Cup played in Atlanta, USA. Four were killed and two survived. One young fighter – Small Jack – was badly wounded but recovered, and the other – Koto Koto (from the sound of an automatic rifle) – hid in his comrade’s gore and pretended to be dead. Koto Koto, one of the youngest combatants, starting when he was 14, then went to jail for assault and rape, which his former comrades said was a miscarriage of justice.Greg Marinovich)

–

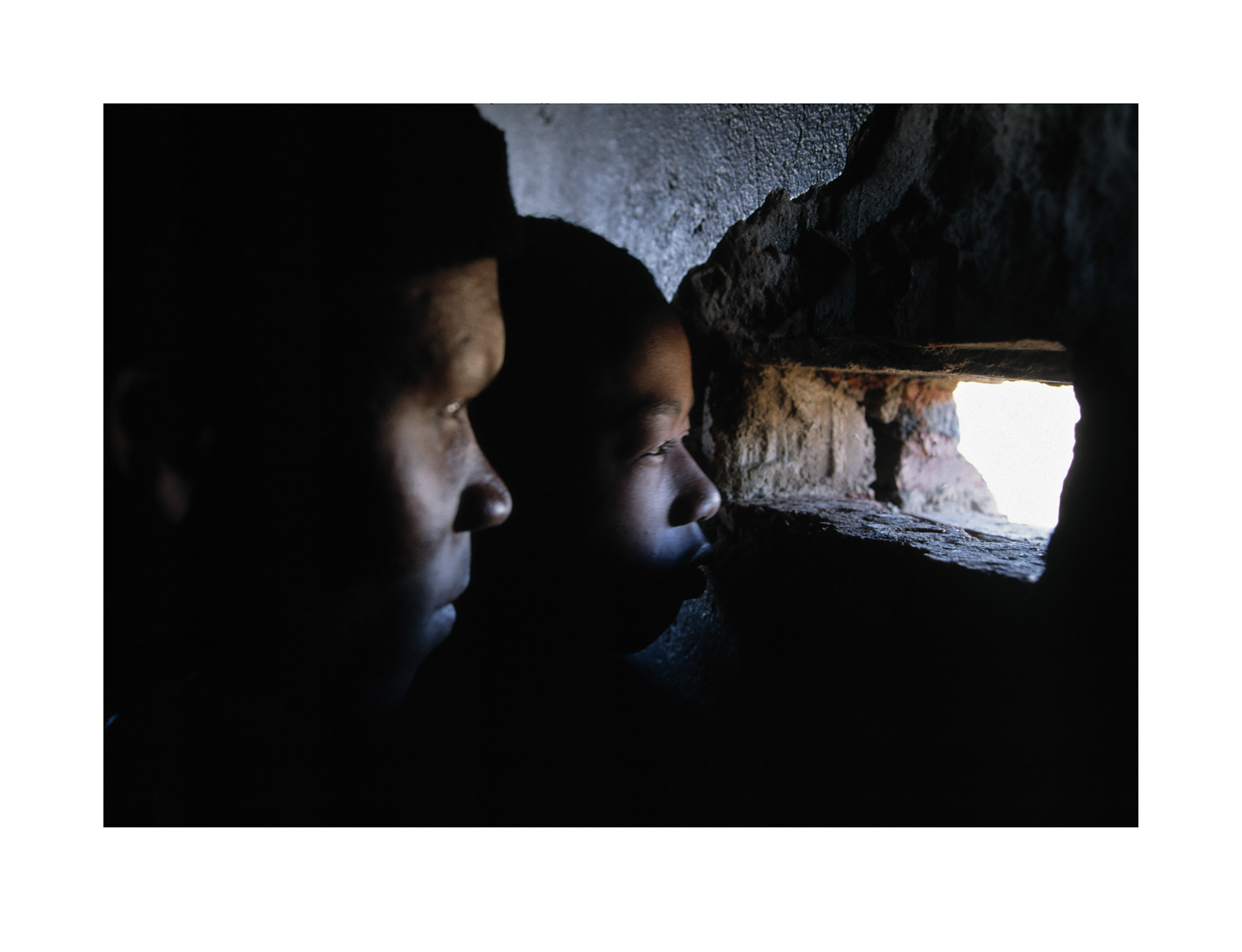

Look-out

Thokoza, 1995

Child soldiers fighting in Mandela Section Self Defence Unit peer towards where their Inkatha enemies hold territory in Thokoza Township. Mandela Section, led by commander Bonga, was one of the most isolated areas of ANC turf abutting Thokoza’s no-mans-land. Photo Greg Marinovich

Thokoza was the war of children, of child soldiers, of street-by-street combat that lasted longer than anywhere else and took the most lives. It had a reputation then as a place of cruelty and death and it carries it still today. Everyone lost too much in that place, resident and hostel dweller. I spent way too much time there.

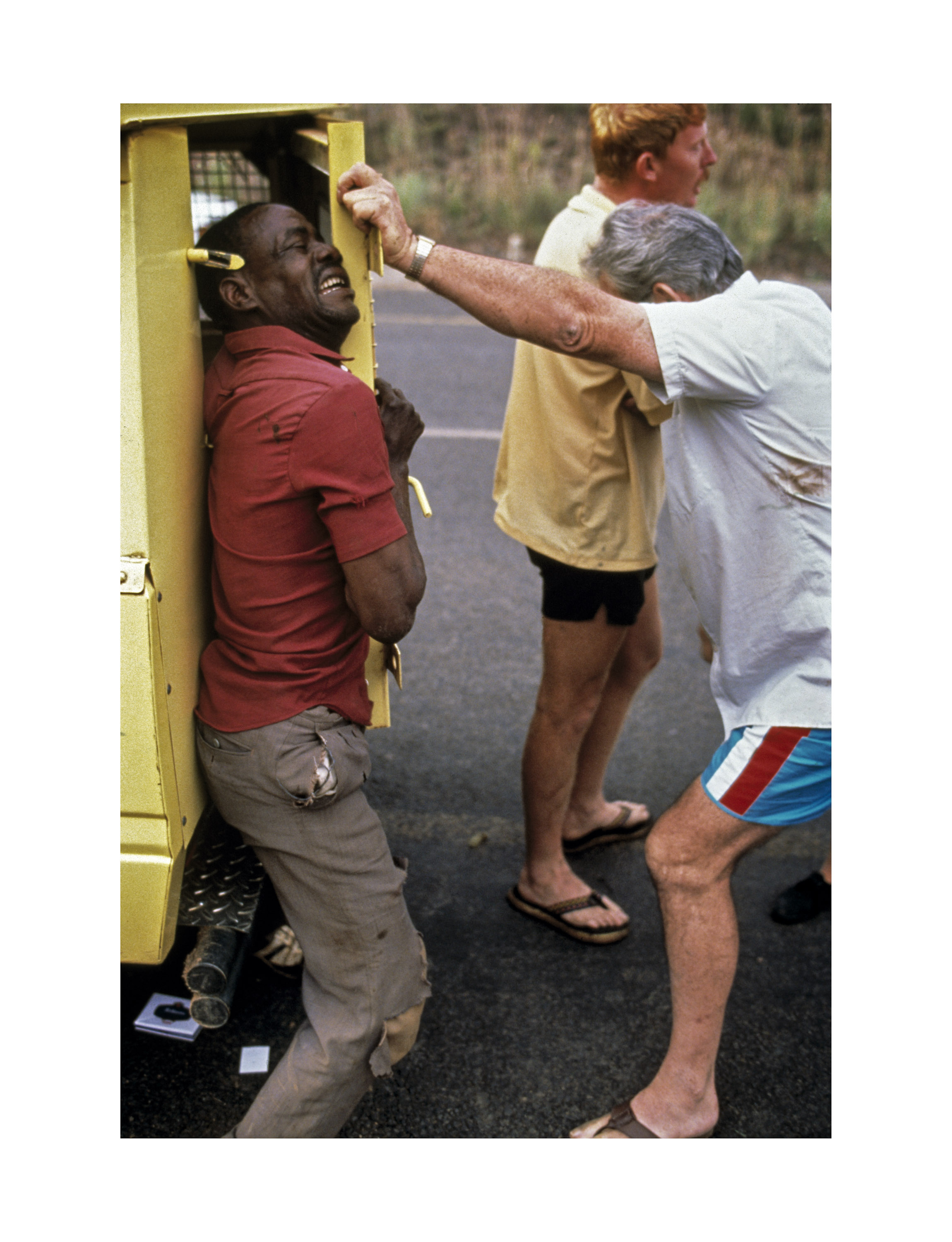

Apartheid, petty & grand

Mandela & Machadadorp

Sunday

Machadodorp, 1992

A policeman and his friend try to arrest a man who was walking drunk along the main road in this small escarpment town. Photo Greg Marinovich

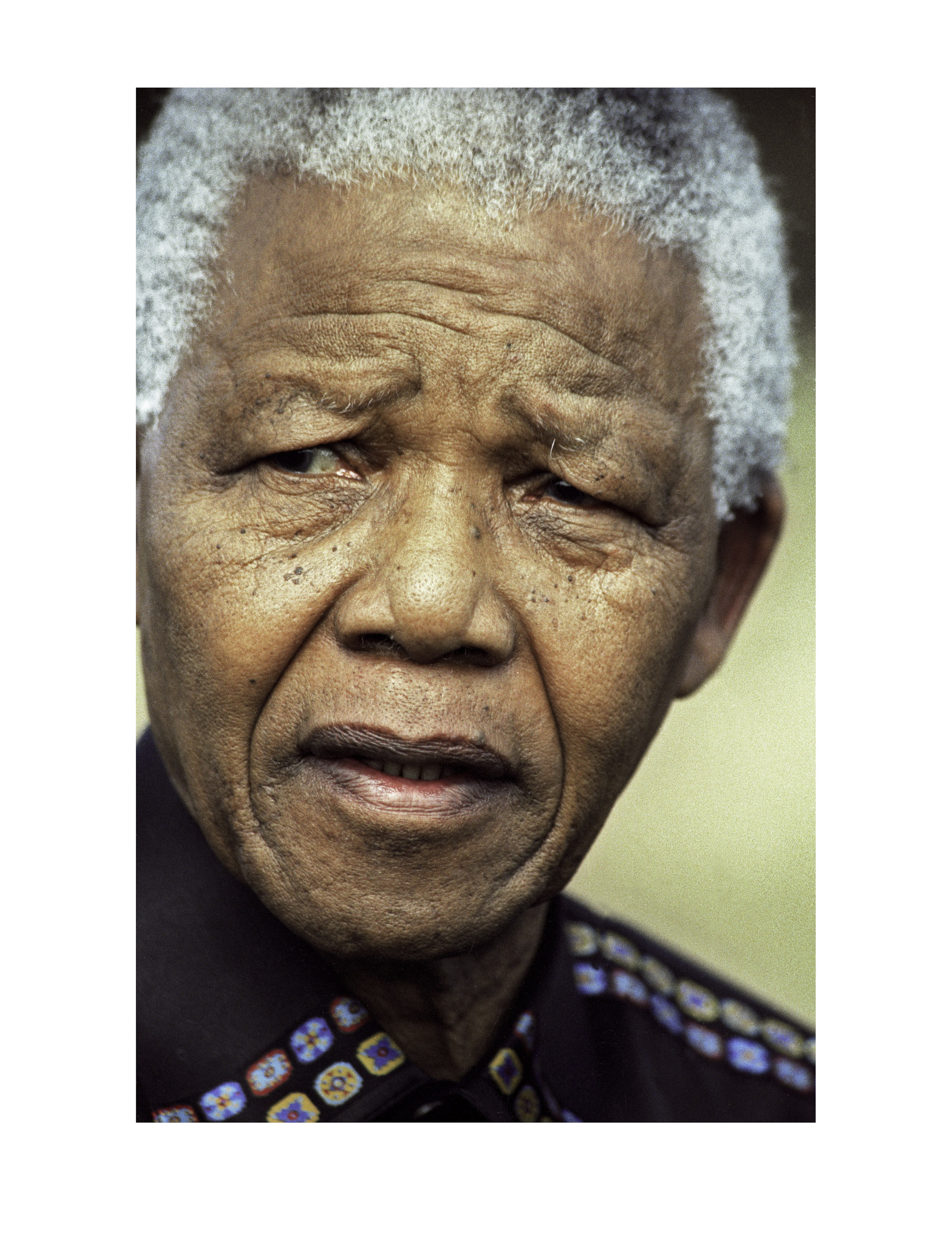

Madiba #2

Richmond, 1999

President Nelson Mandela goes to strife-torn Richmond in an attempt to quell deadly fighting between supporters of his African National Congress and the United Democratic Movement in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands. Mandela angry, as he was on that day, was a far cry from the genial bonhomie that he usually displayed. He was not a man to trifle with. This image was from cross-processed slide film as I had to unexpectedly file images the night I returned from Richmond. Photo Greg Marinovich

Nelson Mandela has both a sainted and a contested legacy, a man we worshipped, relied on and eulogized, yet we seemed to turn on his memory when all that followed him disappointed us. He sacrificed his life to a struggle that he eventually had to compromise on, yet never became bitter, no matter no small his belittlers. DM

Enquiries for portfolios or individual images to Strauss & Co, 89 Central Street, Houghton, Johannesburg, 2198 Telephone number 011 728 8246 / 082 901 1246

Become an Insider

Become an Insider