Explainer

The South African Reserve Bank, minus the political noise

It’s been a rough couple of years for the South African Reserve Bank, through no fault of its own. The political contestation over its mandate and composition, largely between factional interests in the governing ANC but also from the EFF, has been to the detriment of South Africa. The latest splatter arising from the ANC 2019 election manifesto is also unhelpful. Let's cut through the noise and disinformation, and talk truth.

What is the mandate of the South African Reserve Bank?

According to Section 224 of the Constitution:

“The primary object of the South African Reserve Bank is to protect the value of the currency in the interest of balance and sustainable economic growth in the Republic. The South African Reserve Bank, in pursuit of its primary object, must perform its function independently and without fear, favour or prejudice, but there must be regular consultation between the Bank and the Cabinet member responsible for national financial matters.”

What does the ANC want the Reserve Bank to do?

According to the ANC election manifesto launched on 12 January 2019:

“The ANC believes that the South African Reserve Bank must pursue a flexible monetary policy regime, aligned with the objectives of the second phase of transition. Without sacrificing price stability, monetary policy must take into account other objectives such as employment creation and economic growth”.

That is taken directly from the ANC December 2017 Nasrec national conference, which resolved to reaffirm the decision of its 2014 Mangaung national conference that “South Africa requires a flexible monetary policy regime, aligned with the objectives of the second phase of transition. Without sacrificing price stability, monetary policy should also take account of other objectives such as employment creation and economic growth”.

The 2017 Nasrec conference also resolved “the Reserve Bank should be 100% owned by the state” and for government to “develop a proposal to ensure full public ownership”.

So what’s the fuss?

It seems the inclusion of the Reserve Bank paragraph in the election manifesto took some sections of the ANC by surprise in a way that underscored, again, the finely balanced the factional interests.

And so the ANC president and the ANC secretary general were publicly at odds: Party boss President Cyril Ramaphosa described that paragraph in the manifesto was “a wish and an aspiration”, stressing the Reserve Bank’s independence was “sacrosanct”, at last week’s National Treasury’s pre-World Economic Forum briefing before departure for the annual Davos, Switzerland, shindig, while Secretary-General Ace Magashule insisted nationalisation and the broadening of the bank’s mandate was ANC policy.

Such public disagreement among the governing ANC indicates not everyone sings off the same hymn sheet — and that factional interests remain determined to push noisily in their interest, even if that may not necessarily be in South Africa’s interest. Such public division in the top ranks of the governing ANC, with alliance partners chipping in also, is not good for South Africa at a time when the government wants to pursue a sustained investment drive to help kick-start economic growth.

The push for a change in the Reserve Bank mandate also comes from the ANC alliance partners Cosatu and the South African Communist Party (SACP), that in its most recent edition of Umsebenzi called for the Reserve Bank to be “realigned” to give effect to what it called “national developmental imperatives such as employment creation”.

But South Africa already has a number of banks with a focused developmental mandate, including the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), the Land Bank and the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC). Amid the political noise and factional jockeying few are asking the hard questions to get to the bottom of those institutions’ (non)contribution to job creation and economic growth.

What’s the Reserve Bank position on its mandate?

Flexible monetary policy has been in place for about a decade. And inflation targeting a range of 3% to 6% remains a key tool. If inflation is not contained, prices rise and that affects the poor more than the wealthy — and as costs rise due to inflation, there would be other consequences such as job cuts and retrenchments.

Worldwide, job creation, economic growth and development are government responsibilities. And if jobs are not being created despite a swathe of state incentives such as a youth employment subsidy, changing the central bank mandate doesn’t solve the underlying fundamental issues — be it a distrust of government intentions, business’s cut-throat capitalistic hunt for profit generation or other reasons.

If inflation targeting is the issue for Reserve Bank critics — inflation hits the poor and vulnerable harder, from food to transport and fuel — changing the Reserve Bank mandate is not the answer. Again, serious questions must be asked of government with regard to pro-poor policies. What emerged in the parliamentary public hearings on the 2018 value-added tax (VAT) hike to 15%, was that there was a host of progressive taxation measures that could be used as part of government tax instruments and policy.

Officially, the Reserve Bank vision is that the bank “leads in serving the economic well-being of South Africans through maintaining price and financial stability”, with its mission “to protect the value of the currency in the interest of balanced and sustainable economic growth in South Africa”.

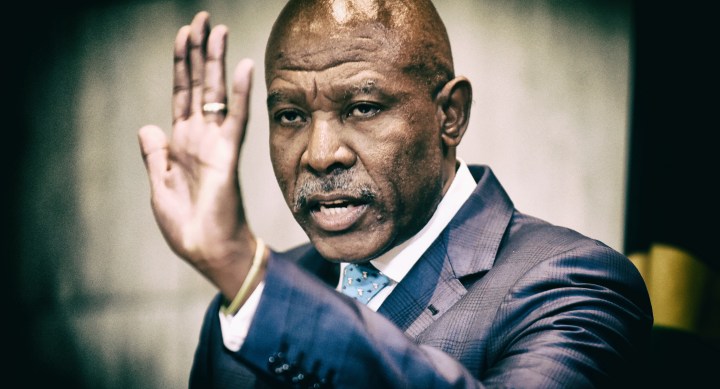

Or as Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago said last week after the first monetary policy committee (MPC) meeting for 2019:

“Our mandate as the Reserve Bank is to protect the value of the currency in the interest of balance and sustainable growth. Anyone who says the Reserve Bank must focus on growth has not read the Constitution… You cannot have sustainable growth if you have imbalances.”

Only a constitutional amendment can change the Reserve Bank mandate, and such a constitutional change requires public consultations, public hearings and an open, transparent legislative process in Parliament. Kganyago said the Reserve Bank would engage with such processes with the intention of protecting the mandate and independence of the bank as it is enshrined in the Constitution.

Didn’t the public protector recommend a constitutional amendment to change the Reserve Bank mandate?

Yes, but it was withdrawn even before a court review of the June 2017 Absa Bankorp report declared it invalid. As part of the court proceedings, Public Protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane’s conduct was criticised from the Bench as, among others, a “somewhat unrepentant alignment with one side of the public debate”.

The public protector’s proposed constitutional amendment to make the Reserve Bank responsible for achieving a “meaningful socio-economic transformation” via a motion in the House from the justice committee chairperson was opposed by both the Reserve Bank and Parliament. In court papers, it was acknowledged that this is not how a constitutional amendment is done.

However, the 19 June 2017 release of the original public protector Absa Bankorp report led to plummeting exchange rates from R12.79 to R13.05 against the US dollar, and the sell-off of R1.3-billion worth of South African government bonds. And the exchange rate was again negatively impacted in early July 2017 when the ANC policy conference proposed nationalising the Reserve Bank.

The International Monetary Fund country report on South Africa in July 2018 noted:

“Following questions about the Reserve Bank’s independence and ownership, market tensions rose. They subsided once the authorities successfully defended the Reserve Bank’s mandate”. The 2019 ANC manifesto surprise put that cycle on repeat.

So what about nationalising the Reserve Bank?

The Reserve Bank has some 650 private shareholders, who by law are excluded from policy-making and its day-to-day running. They also have no say over foreign reserves. Being a Reserve Bank private shareholder is perhaps more of vanity; it doesn’t really pay either. Private shareholder income, or dividends, is capped at a total of R200,000 per annum. That’s R200,000 shared between the 650 private shareholders.

Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank recorded profit before tax of R1.9-billion, according to the 2017/18 annual report. And R1.4-billion of the Reserve Bank income was transferred to the contingency reserve to rebuild reserves, crucial to maintaining monetary stability.

What about the private shareholders’ influence on the Reserve Bank board of directors?

Not much of a say there either. That’s because the president in consultation with the finance minister appoints eight of the 15 Reserve Bank directors, including the bank’s top decision makers — the governor and his/her three deputies.

The remaining seven directors are drawn from a pool of candidates vetted and approved by a panel constituted by the Reserve Bank governor, who has a decisive vote, a retired judge and one other person nominated by the finance minister and three members nominated by the National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac), the statutory structure that brings together government, labour and business.

Will nationalisation make a difference?

On paper and in looks, maybe. In objective reality, no. Although the politicking noise, and ill-considered public protector proposal, would have it differently. And for those worried about a wholesale communist-style takeover, a state-owned South African central bank would be no different to, say the Bank of England (nationalised in 1946) or the US Federal Reserve Bank.

But despite a 2014 ANC national conference resolution on nationalising the Reserve Bank, it’s been EFF leader Julius Malema who has started the move for a legislative change.

In August 2018, Malema tabled a private member’s bill — the South African Reserve Bank Amendment Bill — as a short, sharp seven-page proposal that focuses on deleting the clauses related to private shareholders. It’s not yet moved much through the legislative pipeline, and if it’s not passed before the elections, it lapses as the new incoming Parliament starts on a clean slate — unless its MPs decide to revive proposed laws and other matters.

But of course, getting rid of the Reserve Bank private shareholders comes at a cost — all would have to be bought out at a time the public purse is stretched tight! DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider