See part one here

I. Old story, new evidence

“FS”: an acronym, two simple letters, which in the context of what was being discussed could’ve been mistaken for the two most popular swearwords in the English language — an expression, perhaps, of the people’s rage when they realised what appears to have been stolen from them, and by whom.

“FS”: the preferred acronym, as it happened, for Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Financial Services. On the afternoon of Tuesday 26 June 2018, in the central auditorium of the Rustenburg Civic Centre, this is what Advocate Benny Makola, the evidence leader at the Baloyi Commission, had to say about it to Advocate MS Baloyi herself, the commission’s new chairperson.

“Chair, you will recall there are mining assets here and land owned by different companies, but whenever these companies sell these underlying assets, the money does not go to these companies, it goes to FS. FS is in Johannesburg. FS, what does it do?”

A fundamental question, to which Advocate Makola appeared to have the outlines of an answer. FS was supposed to be a “corporate financial entity”, he explained, but the accountants had flagged a problem – there were large “consultant fees” attached to the entity, and yet no notes in the financial statements as to what these fees might entail.

“I am giving that as an example of why,” Makola continued, “the [Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council] must be placed under administration. I am not even talking about criminal activities. I am just talking about failure to comply, whether or not criminal activities happened. I do not have enough to work with. All I know is that the Companies Act, no compliance; Income Tax Act, no compliance; Provincial Act, no compliance.”

Since Daily Maverick first highlighted these issues on 1 February 2018, in a 6,500-word investigative feature that, we argued, may have pointed to the largest government-sanctioned, business-perpetrated fraud in the history of Big Mining in South Africa, a lot more has bubbled to the surface regarding the size of the scam.

Back then, taking in the major deals signed by Kgosi Nyalala Pilane— the disputed but still de facto regent of the Bakgatla – with major international mining houses such as Anglo Platinum and Pallinghurst Resources, we estimated that around R25-billion in assets and capital had been stolen from this community of 350,000 mostly unemployed South Africans. As it turns out, we may have low-balled on our number.

In a report submitted to the Baloyi Commission by the Land Access Movement of South Africa (Lamosa) in June 2018, evidence that could not be properly corroborated in February was finally put forward. The storyline hadn’t changed, it had just got a lot longer: yet more illicit transactions and money flows through the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council; yet more nigh-impossible-to-decipher financing arrangements; yet more blatantly fraudulent consultant fees.

“Most of the baseline references are not new,” noted the report, “but the latest newly discovered information confirms in some instances what could only be deduced from the older material.”

The people at Lamosaalso stated this:

“The report covers factual issues, which should not be in contention, and makes preliminary observations on the factual evidence. It attempts to do so in a balanced and thematically structured manner, to guide the reader in connecting the dots and comparing like with like and avoiding repetition.”

As the reader may remember from the first feature, the Maluleke Commission – which was the name by which the Baloyi Commission was known before the death in August 2017 of Judge George Maluleke – had served up a series of complications and perplexities that, at one time or another, undid the advocates and lawyers, the accountants and auditors, the historians and genealogists, and even the chair himself.

The inquiry was always supposed to be focused on Kgosi Pilane’s “legitimacy” as chief of the Bakgatla, and although the mining houses, who had been the major behind-the-scenes architects of the alleged corruption, had never (and would never) make an appearance, the evidence had unavoidably come around to what the commission euphemistically called “maladministration”.

But again, if this was indeed the largest fraud committed by Big Mining in democratic South Africa, it was the ordinary members of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela who should by then have been recognised as the primary victims – the people on the receiving end of the most sophisticated and profitable con job to ever hit a post-apartheid mining community.

“We know there is a problem about this information,” said Advocate Makola with respect to the above-mentioned FS, “because we do not have a source document, and one does not suggest that they must give these big boxes… but give the community a 45-pager that says X approached us, they want to do a transaction with us, the effect of the transaction is that you people must leave your grazing, your homesteads and everything, you must go and live in Geelhout and there is a meeting that is going to happen on X date… you surely want to see documents about this, come to the office, we are open between 8 and 5. No, they do not do that.”

- Villages surrounding the Pilanesberg Platinum mine in the North West in South Africa have severe unemployment, lack of basic infrastructure and are without running water, despite being on one of the riches reserves of platinum in the World. The owners and tribal chief in the area are accused of stealing over R25 billion that was supposed to be spent on developing the surrounding area. Photo: Daniel Born

What follows, then, is some more of what Kgosi Nyalala Pilane, the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council, a few of the world’s richest mining houses, a major South African investment bank and a top-tier local law firm did and did not do.

II. The place of the professionals

It all seems to have started in 1998, two short years after Nyalala Pilane was appointed kgosi, when he went to the Land Bank to apply for a loan – what he was after, according to the evidence, was a pair of additional farms in a place called Dwaalboom. As per the documentation obtained by Lamosa, Pilane applied for the loans in his personal capacity, but “told the Land Bank he was authorised to act on behalf of the BBK tribe.”

In support of the application, he stated: “The Bakgatla Ba Kgafela trust and/or the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela tribe will receive an annual net income of R6,206,367 in royalties from mining.”

So the Land Bank granted Pilane a loan of R12.875-million, Pilane bought the farms, and Pilane’s “subjects” never saw a cent in royalties. What’s more, he defaulted on the loan repayments, forcing the Land Bank to take legal action. By 2006, Kgosi Pilane’s debt had ballooned to a little north of R26-million.

The community, however, had been onto him from the get-go. In February 2001, at community members’ insistence, the office of the North West premier conducted an audit of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council’s financial statements for the years 1997 to 2000. Irregularities were quickly identified, but somehow the asset control registers were unavailable.

In 2003, the South African Police Service (SAPS) Commercial Branch in Potchefstroom opened an investigation into fraud, theft and possible corruption in Pilane’s office, and in June 2004 SAPS conducted a search and seizure operation at this office as well as at Pilane’s house. Among the allegations of the community members were the following: no financial records had been provided since the appointment of Pilane as kgosi in April 1996; companies were not paying royalties to the trust account of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council; zero benefits or proceeds were going to the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela from the Dwaalboom farms; and there was (as above) a fraudulent application for a loan from the Land Bank to the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela.

- Under the land that belongs to the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela lie the richest platinum deposits on Earth. But a toxic alliance between government, traditional chieftaincy and major mining houses has stood between the community and its wealth. Photo: Daniel Born

In May 2006, the Asset Forfeiture Unit froze bank accounts and attached assets registered in Pilane’s name, including farms, businesses and vehicles.In November 2006, Pilane was charged by the Mogwase regional court on two counts of fraud, one count of corruption, and 43 counts of theft. In June 2008, he was found guilty; in April 2009, sentenced. But in September 2010, the conviction was set aside on appeal.

As it turned out, the famous Kemp J Kemp SC, who had been known to get former president Jacob Zuma out of a few tight spots, zeroed in on the technical point that allowed Pilane to walk free. Which was very interesting, because the years 2006 to 2010 coincided with three other events that would come to shape the narrative: the settlement of Pilane’s R26-million Land Bank debt, and the two joint venture deals, as outlined at length in Daily Maverick’s first article of this series, with Rustenburg Platinum Mines (RPM; a division of Anglo Platinum) and Pallinghurst Resources.

“The repayment of Land Bank loans was a key factor throughout the negotiations,” noted the Lamosa report of the R435-million deal between the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Councila nd RPM.

“Both RPM and [consulting firm] Resource Finance Advisors were in direct communication with the Land Bank regarding the outstanding amount owed by Kgosi Nyalala Pilane.”

The report then continued: “It is unusual for the main counter-party in a sale transaction to be involved in the settlement of private debts owed by an individual, particularly if that person represents the entity investing or acquiring shares in their company. It is also concerning that the final transaction agreements were structured specifically to ensure repayment of private debts to a third-party creditor.”

And that wasn’t the only thing that may have demonstrated Anglo Platinum’s reluctance to engage with the facts about Kgosi Pilane. In February 2007, four months after he was charged by the Mogwase regional court for fraud, corruption and theft, Pilane was appointed as a director of companies that held significant shareholdings on behalf of the community under the RPM joint venture agreements.

In their response to Daily Maverick on 2 November 2018, Anglo Platinum stated the following:

“This issue is of great concern to us. The company is investigating the matter and will take the appropriate action once we have conclusive information. We can confirm that a loan was extended to the traditional authority in connection with the settlement of that authority’s indebtedness to the Land Bank. In extending the loan, the company sought and received confirmation from the Land Bank of the existence and the extent of the traditional authority’s debt before extending the loan. The loan was extended to the traditional authority and not to the former kgosi.”

It was a response that left Daily Maverick’s two most important questions unanswered: a) was Anglo Platinum aware of the charges against Kgosi Pilane at the time, and b) if not, why not? This same set of questions also went unanswered by the firms that helped Anglo Platinum to structure and implement the deal – Rand Merchant Bank and Werksmans Attorneys. As Lamosa’s source documents demonstrate, RMB advanced a loan of R435-million in debt financing to a company called Lexshell 36, one of the four on which Pilane had assumed a directorship in February 2007, in order for the Bakgatla to acquire a 15% stake in RPM’s Union Mine. Aside from its upfront R4.78-million structuring fee, RMB placed a clause in its loan agreement about “forward hedging cover” to counter the risk of changes in the price of platinum. It was this clause that would contribute to the R750-million in loan repayments that it cost the Bakgatla to settle both the debt facility and the hedging cover with RMB.

On these last points, the top-tier South African investment bank sent the Daily Maverick(via email on 2 November 2018) an unyielding response: “RMB is satisfied that, based on its due diligence at the time, the parties who entered into the transaction had the necessary authorisation to do so. The transaction was approved by the Bakgatla-Ba-Kgafela community on 25 November 2006. For further information in this regard please refer to the SENS statement released by Anglo American Platinum dated 14 December 2006.

“Please note that a metal price hedge is not unusual, but common practice to provide downside protection to the entity involved to raise commercial funding for the transaction.”

Which, while it may well have been the case, didn’t address the primary concern in Daily Maverick’s questions to the bank: was RMB aware that 350,000 mostly unemployed members of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela would be liable for the above debt?

“Kindly furthermore appreciate,” they said, “that the community was not advised on this transaction by RMB, but appointed their own advisers.”

So to come back once more to Advocate Makola’s point at the Maluleke Commission – the ordinary members of the Bakgatla knew nothing, at any time, about the extent of the financial havoc that was being wrought in their name. And among the people and institutions who may have neglected to inform them were the lawyers at Werksmans, who were instructed to make payments from a trust account for legal and advisory costs in accordance with the provisions of the RMB loan.

As per the Lamosa report, this was problematic for the following reason:

“It has not been possible to properly account for the disbursement of these funds, because payments for advisory fees have been effected from two different trust accounts.”

Werksmans, for their part, did not acknowledge receipt of Daily Maverick’s questions – emailed to brand and communications manager Hawa Moya, after a brief phone call, on 29 October 2018.

III. Crimes, dimes and slimes

Still, by far the largest enabler in the R25-billion-plus fraud that Kgosi Pilane delivered upon the people he purports to lead was the multiple-tax haven-registered mining conglomerate known as Pallinghurst Resources. Daily Maverick has already laid out in some detail the series of “logically sequenced transactions” through which the conglomerate – under the direction of noted mining luminary Brian Gilbertson – acquired three adjacent platinum deposits on the western limb of the Bushveld Igneous Complex. To briefly recap, a joint venture was set up between Pallinghurst and the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council, the shareholders and investors were registered in places like Guernsey and Mauritius, and no attempt was made to seek the consent of the community members who were living on the land under which the deposits sat.

In other words, from the standpoint of Kgosi Pilane and the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council, the modus operandi hadn’t changed. The only difference with the Bakgatla Pallinghurst Joint Venture was the size of the assets under consideration. By the conclusion of the deal in 2012, the BPJV would own the vast majority of the mineral rights of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela, a significant chunk of the largest platinum deposits on Earth.

Once again, the new documents that have come to light regarding this deal confirm what was known and published by Daily Maverick on 1 February 2018. Currently, the joint venture’s single contiguous mega-mine is still valued at between R20-billion and R25-billion, and the 350,000 South Africans that comprise the wider Bakgatla community have still not seen a cent in dividends. But because it is emblematic of the brazenness of the venture, it is probably worth homing in on one particular piece of new evidence – a certain payment of R369.5-million that remains unexplained.

According to the Lamosa report, this amount was somehow related to a R340-million “success fee” that was payable to the transaction advisors engaged by the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council, RFA Consulting – a reward, in other words, for negotiating a 40% stake for the Guernsey and Cayman Islands-registered Pallinghurst Investor Consortium in one of the three farms that held the platinum deposits.

“On 2 May 2012, an amount of R 369,499,415 was credited to a Nedbank Corporate Saver Investment Call account operated… on behalf of the Bakgatla Ba-Kgafela Tribe,” stated Lamosa.

“However, details of the subsequent disbursements do not include an electronic transfer of this amount to RFA Consulting.”

Nobody knows, it seems, where the R369-million went; neither the various gentlemen who testified about it at the commission, nor the forensic accountants who were tasked with following the trail, nor Pallinghurst Resources, who told Daily Maverick to “ask the BBKTC”. As with the first piece, all questions sent to Pilane and the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council went unanswered. What we do know, however, is that there is reason to believe that the deceptions haven’t stopped.

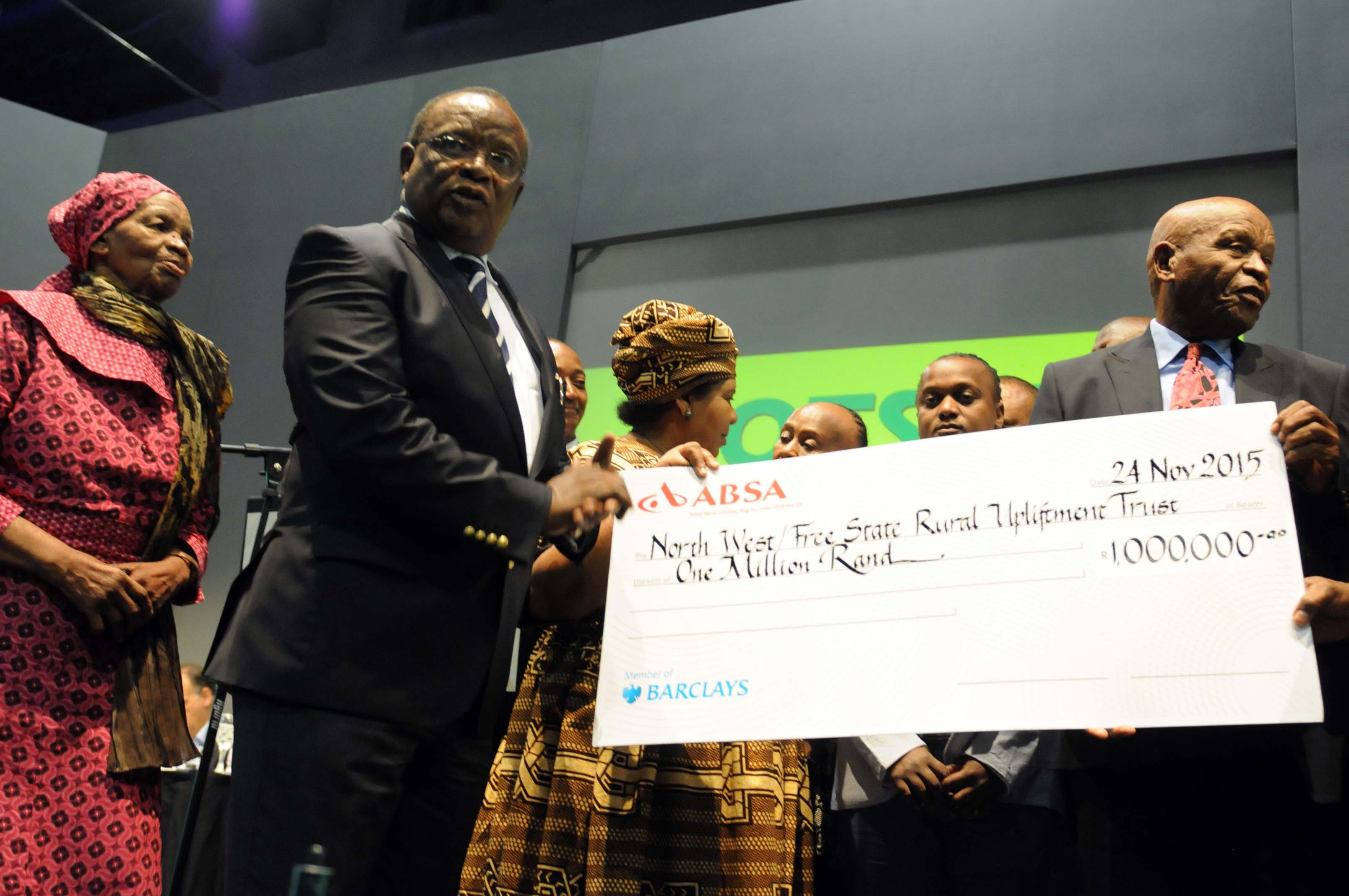

- Bakgatla ba Kgafela chief Nyalala Pilane during a function where Patrice Motsepe donated money to traditional leaders and churches on November 24, 2015 at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Sowetan / Peter Mogaki).

Back in April 2009, when the court sentenced him for fraud, corruption and theft, Kgosi Pilane had been forced to resign his directorships of the Lexshell corporate entities established on behalf of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela community. But in 2017, when Anglo Platinum announced the sale of its interests in Union Mine to a consortium made up of Siyanda Resources and the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela, Kgosi Pilane was reappointed to the board of Lexshell 36. His brother, Kagiso Pilane, was meanwhile appointed to the directorships of (other) companies that were central to the transactions. On 1 February 2018, Siyanda Bakgatla Holdings took ownership of Union Mine.

The day before, the Department of Mineral Resources had accepted an invitation to a small affair to celebrate the deal. Present at the festivities, according to the DMR’s Facebook page, were former Minister Mosebenzi Zwane, North West Premier Supra Mahumapelo, Anglo Platinum CEO Chris Griffith, Siyanda Resources chairman Lindani Mthwa, and Kgosi Nyalala Pilane himself.

With respect to Pilane’s background as a convicted fraudster, DMR informed Daily Maverick on 2 November 2018 that it “considers the requirements as contained in the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act when assessing compliance, and not individuals or their history”. Also, addressing delegates at the function back in January, the minister had the following to say: “This transaction proves that radical economic transformation is not a painful exercise and it can be achieved.”

As for the Bakgatla community, which purportedly now owned 27 percent of the issued share capital in Siyanda Bakgatla Holdings through Lexshell 36, things were less “provable”. In the words of the Lamosa report:

“A single shareholders’ agreement and an unsigned, undated DMR Section 11 application is insufficient information to determine whether this deal was in the best interests of the community.”

To judge by the deals of the past, and not discounting the apparent eagerness of former Minister Zwane and the bosses of Anglo Platinum and Siyanda Resources to jump into bed with the likes of Mahumapelo and Kgosi Pilane, it is doubtful that this deal will benefit anyone but the immediate signatories. Indeed, the list of grievances that the ordinary and unconnected members of the Bakgatla could have held against the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council and Kgosi Pilane, if only they’d had the relevant information, is close to endless.

For instance, the Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company, which was set up by Kgosi Pilane in February 2010 to bring economic development to the region, did nothing of the sort. The purpose of the Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company, as articulated in its mission statement, was “to create a viable and sustainable economic system that attracts value-adding participants and investments, thereby contributing to the reduction of poverty, unemployment and inequality within our tribe and local communities”.

One of the ways they went about this, according to the Lamosa report, was by paying a salary of R92,000 a month to Martha Tsheole, a woman who happens to be the sister of Nyalala Pilane and the mother of Mpho Tsheole, Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company’s managing director. And so, unsurprisingly, all the companies in which Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company chose to invest have sustained significant losses. What’s more, in his expert report to the Baloyi Commission, forensic accountant George Papadakis stressed the “unreliability” of the financial statements of Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company. Papadakis also found that the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council “had not properly accounted for its loans and investments in BBKSIC and its subsidiary and associate companies.”

No doubt, further digging in the mountain of documentation that the commission is bringing to light will reveal what happened to the hundreds of millions that passed through the various accounts of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council and Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company.

“According to the draft annual financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2015,” noted Lamosa.

“BBKSIC had received loans in the amount of R248,405 million from the BBKTC.”

Of this amount, Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company advanced R165 million to its subsidiary, associated and related companies, which was mainly used to cover operating expenses.

“Since then, the salary bill of BBKSIC and its entities has further increased by almost R75-million,” Lamosa continued. “[But] the operating expenses incurred by these companies for the period 2016 – 2017 are not available.”

Given that companies in which Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company invested have been technically insolvent since 2013, there is almost zero chance that the loans will be repaid. Left carrying the can, of course, are the very people whose poverty the Bagkatla Ba Kgafela Strategic Investment Company was set up to reduce.

Ultimately, it all points back once again to what Daily Maverick, Lamosa and the Land and Accountability Research Centre have long been suggesting is one of the most heinous and unheeded frauds of post-1994 South Africa. If the authorities ever got their collective ducks in a row, they would find, according to Lamosa, that they had some work to do. The criminal elements of the case would be circumscribed by, amongst others, the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (where the BBKFS engaged in financial services without FSB approval); the Prevention and Combatting of Corrupt Activities Act (where Kgosi Pilane and his various henchmen and –women robbed the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela blind); and section 39 of the North West Act (where there was a failure to invest surplus funds with the premier’s approval).

On the civil side, the Companies Act would cover reckless trading and the various directors who are personally liable to “pay back the money”. And then, on the administrative side, things would properly begin to heat up. Here, the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants and the various law societies would be called to bring into line the army of professionals who had either blatantly ignored or actively encouraged the fraudulent activities of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Council.

There has, of course, been one piece of good news to come out of the whole sordid saga: on 25 October this year, the Constitutional Court found in favour of the BBK’s Lesethleng community in their protracted battle with Pilanesberg Platinum Mines (owned by Pallinghurst Resources through Sedibelo Platinum Mines) and Itereleng Bakgatla Mineral Resources. The court overturned an eviction order that would have forced the community off its land, ruling that the companies had failed to “meaningfully consult” according to the requirements of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act and Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act.

But again, what about the mining bosses themselves? What about the various dealmakers and their enablers who have so far gotten off scot-free? Would President Cyril Ramaphosa’s people have the balls (or the inclination) to go after them?

The answers to these last questions, it’s obvious enough to say, will provide a great clue as to South Africa’s future development path. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider