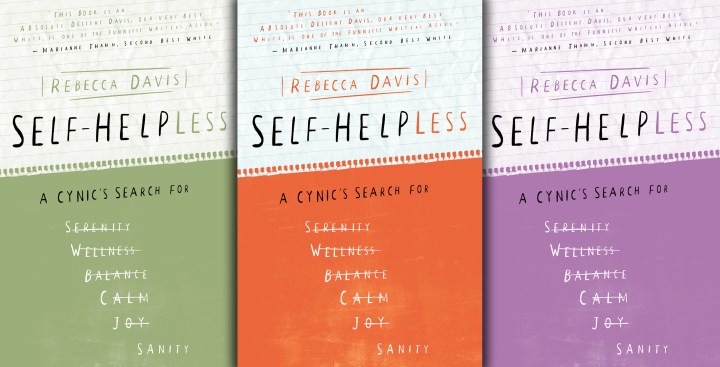

Book Extract

Self-Helpless: Losing the plot to social media

In recent times, the self-help industry has exploded into a multi- billion dollar global industry – and along with it has come every imaginable type of therapy, healing or general woo-woo. In the past, Rebecca Davis scoffed at this industry, mocking its reliance on half-baked science and the way it appears to prey on the mentally fragile. But as she searched for a meaning of life that did not involve booze, she found it increasingly hard to rationalise her default scepticism. In this extract from her latest book Davis writes about battling the demons of social media.

My social media wake-up call came on Easter Sunday, 2017.

I was in Johannesburg, savouring a delicious breakfast painstakingly prepared by my sister-in-law. There were buttery croissants. The sun was bathing the table in a warm autumnal light. I was enjoying the company of family.

Then: a notification on my phone. Red flag. Facebook. Alert! Danger! Emergency!

Somebody – a total stranger – had taken offence to an opinion piece I had written earlier that week. She had composed a disparaging paragraph outlining what she considered to be the errors in my argument.

My heart started pumping like a drum. Blood rushed to my ears. My reaction was as reflexive as breathing.

Muttering an excuse, I stood up from the breakfast table immediately and started pacing and typing, furiously hammering out a rebuttal.

This cretin needed to be corrected at once. Who did she think she was, taking me on in this manner in public? How dare she broadcast her misguided critique for all to see? What if people thought she was right? How would I –

“What are you doing?”

Haji’s voice penetrated my frenzied mental and digital activity. I looked up.

“Sorry, it’s just someone—“ I began.

And then I stopped. In a moment of clarity like a sunbeam breaking through the clouds, I suddenly understood exactly how insane what I was about to say really was.

A stranger disagreed with me on the Internet so I had to leave a family meal to set them straight immediately.

“It’s nothing,” I said, putting down my phone, and I walked back to the breakfast table.

***

In the course of the decade during which Facebook insinuated itself into my life a little more every year, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this website was making us lose our fucking minds.

I was watching people I deeply admired offline engage in objectively insane behaviour online.

They were fishing for compliments or attention in a palpably desperate fashion. They were advertising a lifestyle or emotional state which I knew bore little resemblance to their real-world situations. They were flying off the handle at the least provocation, spitting furious invective in response to any form of disagreement.

As I have previously observed elsewhere: it was like everyone was drunk, all the time. And I was no different.

***

Facebook turned out to be a gateway drug for me. The real Class-A stuff was Twitter.

The snarky, edgy, mean-girl tone of Twitter was my mother tongue. I was born for this place.

Finding Twitter felt like stumbling upon the local bar you’ve been looking for your whole life: an establishment where everybody knows your name, and everybody is as engaged with politics and news as you are, and everybody’s always up for some cynical banter.

Compared to Twitter, Facebook felt like a boring kitchen tea – one where all the guests are fake-nice to each other in public, and then go home and stick pins into dolls behind closed doors.

Twitter was a blood sport. Here, all the animosity, all the resentment, all the rage, was lying exposed for all to see. People didn’t pretend to be nice. “Nice” was irrelevant. All that mattered was whether you were right or wrong.

When you found a viewpoint you agreed with, you endorsed it to hell and back. You said it was the truest thing any human had ever said. This. Finally.

When you found a viewpoint you disagreed with, you gathered up a mob of like-minded comrades and went after the offender with pitchforks in hand.

This wasn’t “social media”. It was war: a battlefield of ideas where only the strongest would survive.

And for a while, I was winning. By April 2017, I had 41 000 Twitter followers. Sometimes I used to picture them filling a small stadium. I specifically enjoyed the word “followers”, for its Biblical associations. It made them sound like my disciples.

I knew that my reign was as tenuous as that of a South American general after a poorly executed military junta. My downfall could come at any moment.

This element of gambling is what makes Twitter so addictive. There is risk every time you press the post button. Have you finally gone too far? Will the mob turn on you today? There is always a sense that your final unmasking, your definitive public shaming, could be moments away.

Where will you hide when it comes?

But when you roll the dice, post that tweet, and the “likes” start rolling in, and you realise you’ve gotten away with it again, you’ve hit the sweet spot of public opinion again – then the tide of euphoria and relief that floods your system is more powerful than it has any right to be.

***

I hadn’t realised how badly I’d lost the plot to social media until that fateful Easter Sunday in Johannesburg when the scales fell from my eyes.

Over the course of a decade, I’d transformed from someone who prided myself on not particularly caring what other people thought of me, to someone who allowed strangers on the Internet to completely dictate the mood of my day.

I was devoting thousands of hours per year to a perverse form of unpaid labour: trying to get people to like me online, often at the expense of my most meaningful real-life relationships.

It was pathetic.

I also realised the extent to which I had allowed Twitter, in particular, to shape my perceptions of the world.

Nobody I knew interacted offline in the way they did on Twitter: with such disproportionate anger or enthusiasm in response to trivial stimuli. Nobody I respected had such hair-trigger black and white takes on complex issues if you sat down and actually talked to them.

Yet I had come to see Twitter as real in a bizarre way: as corresponding to a legitimate microcosm of South Africa and the world. It had left me feeling bleak and hopeless – about the possibility of racial reconciliation, about the potential for gender equality, about the chance of any kind of meaningful accord between people of varying political views.

This was despite the fact that what I encountered in real life often told me something quite different.

I felt like I’d fallen prey to a form of Stockholm Syndrome, where after sufficient immersion in a toxic environment I’d begun to enthusiastically participate in my own poisoning.

Back in Cape Town after Easter, I pulled the escape cord.

I quit Facebook altogether, but I couldn’t bring myself to delete my Twitter account completely: partly because I was too weak, and partly because I would need Twitter again to promote this book.

But I logged out. I deleted the apps off my phone, and on my laptop I installed a plug-in that would block me from Facebook and Twitter if I attempted to re-access the sites. The plug-in was my saviour. In the weeks to come, I would sometimes absent-mindedly click on a link leading to Facebook or Twitter, and instantly be confronted with a stern message of rebuke. Not only did the plug-in not let me access the sites, it also made me feel terrible for even thinking about it.

“This is the third time you’ve tried this,” the message would say. Or just:

“REALLY??!”

Its disappointment in me was palpable through the screen, and I would retreat, ashamed. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider