Foreshore Freeways Project

End of the road for a Brave New Cape Town

The future for the Cape Town City Bowl simply has to be tall and dense if it is to equitably accommodate more people. Elegant and sculptural high-rise towers offer a Hong Kong or Singapore-like future for our city, and therefore the opportunity for ordinary citizens to have a real stake in central Cape Town – even if that stake takes the form of a 30 square metre bachelor studio.

Patricia de Lille promised to be the first mayor of Cape Town (or indeed any South African city) to take a real interest in the spatial transformation of the city.

While political and (then) economic transformation have both been at the top of the ruling party’s agenda since 1994, the elephant in the room remains in the form of apartheid’s most visceral and potent legacy, that being the spatial and racial segregation that continues to stunt our cities.

And Cape Town’s transport network, designed more in the service of segregation than efficiency, is bursting at the seams – with the poor (as usual) taking the brunt of it.

Cape Town is still reeling from 50 years of apartheid town planning. Twenty-four years since the end of apartheid, the poor still commute into town from their dormitory townships, while the wealthy largely still commute from the suburbs. And the resultant social instability affects us all, in sometimes cruel and violent ways. It also makes us all poorer.

The spectacular collapse of the City of Cape Town’s Foreshore Freeways Project (due to political infighting, administrative incompetence and perhaps even fraud) has left me personally disappointed as a Capetonian, more so even than in my capacity as architect of the preferred bid by MDA, the winners of stage one of the tender. Because our bid offered the real opportunity (and maybe the last opportunity) to fix the city’s most burning structural problems.

In a city of 3.5 million people, where only around 250,000 get to live in its prosperous core, the freeway system forms a lifeline to the hard-working ordinary Capetonians who depend upon it for access to the opportunities and resources of the City Bowl and Atlantic seaboard.

But not everyone is disappointed. In fact, some are relieved, because the Foreshore Freeways are not a popular cause among certain middle-class Capetonians – particularly those dwindling few who are already sorted for transport and housing.

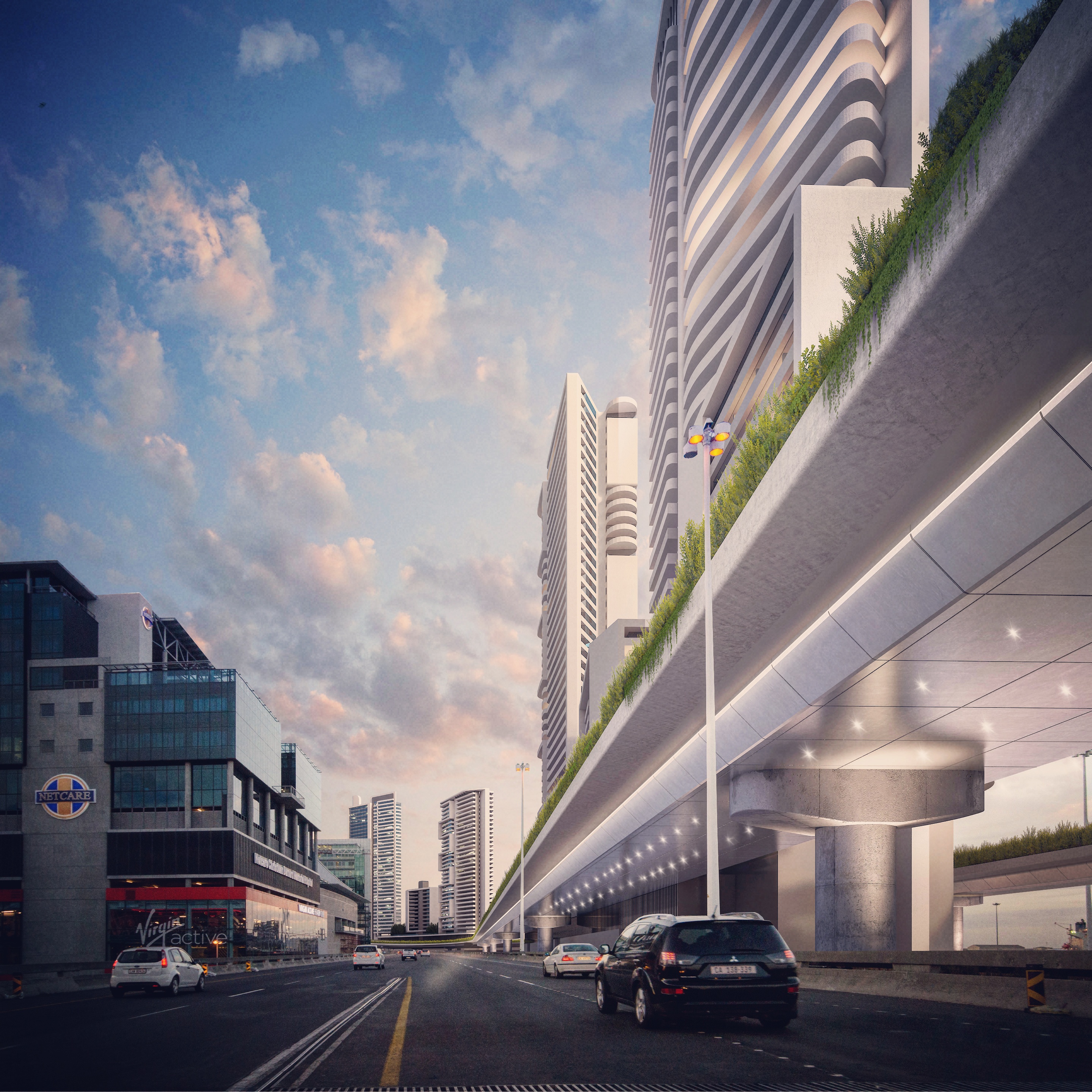

Cape Town cannot afford to bury its freeways, but we can afford to complete the ones we already have. Artist’s Impression © 2017 Robert Silke & Partners

One must bear in mind that the freeways’ non-completion in the Seventies was not solely due to budgetary constraints, but was rather stopped by (white) public pressure, essentially objecting to the idea that the flyovers would somehow “cut the city off from the sea” – which is the “conservation” argument.

But the legitimate interests of conservation are, all too often, abused as cloak and cover for conservatism and nimbyism (not-in-my-back-yard). Our sentimentalism drives us to yearn for James Ford’s depiction of a Victorian future Cape Town.

James Ford’s “Holiday Time in Cape Town in the Twentieth Century”, 1899

And wishing away the freeways is a similarly nostalgic preoccupation. The “conservationist” dream of a low-rise restoration of Victorian Cape Town leaves no room to imagine a place for others who have been historically excluded from that vision.

Anyone who has ever actually walked under the freeways will know that it is the harbour and its security fence that cuts off the city from the sea – and not the freeways.

The elevation of the freeways makes them visually permeable and physically permeable. You can literally see through them and walk underneath them. But Cape Town has failed abjectly to positively utilise the space under the freeways, and it is this that has created the barren no-mans-land underneath. The land is unzoned and undeveloped.

There are successful city environments around the world, and particularly in Far Eastern cities such as Shanghai and Hong Kong, where freeways are elevated far higher than ours, and whole worlds of neighbourhoods and shopping districts exist harmoniously underneath – and they form no barrier whatsoever. People should be living, working and shopping both under and over the freeways.

In essence, we proposed to finally complete the Foreshore Freeways, constructing them not simply out of concrete and asphalt, but to literally make them out of the only true building blocks of sustainable cities – affordable housing. And the cost was to be entirely borne by the development of upmarket and midmarket housing.

Rather than planning the new viaducts as fly-overs with dead space underneath, the roads were to be constructed from three storeys of accessible, affordable non-subsidised housing units. Housing units are the lego from which great cities are built, and are the building blocks from which our new viaducts were to be constructed.

The activation of these notorious areas of dead space under the flyovers would urbanise and animate these wastelands on the periphery of the CBD, and help to transform Cape Town into a world-class city of equal opportunity and spatial justice. We weren’t proposing a Disneyland here, but rather, decent, ordinary city streets.

End of the Road for Brave New Cape Town. Artist’s Impression © 2017 Robert Silke & Partners

We promised an absolute minimum of 450 genuinely affordable housing units, ranging from 20m2 to 40m2 – in turn subsidised by 3,200 “free-market” sectional title units being sold at conservative selling prices. But by nominally raising the selling price of the free-market housing, we had the cross- subsidisation potential to more than double our quantum of affordable housing units. Housing activists acknowledge that our bid was the most earnest and transparent in its social housing model.

And even for the free-market housing, we’re referring to accessible units. Apartment sizes were kept small – with thousands of units only 30-35m2 in extent – making many more thousands of new residential opportunities available in the city centre for people who couldn’t previously afford to come here. And there’d be commensurately thousands fewer cars on our roads as a result.

Landed middle-class people can be traditionally resistant to the large-scale development of new housing stock – generally predicated on the fear that the oversupply of new housing will devalue their own established housing assets, but this essentially commercial opposition is rather expressed in the form of the usual bogeymen of congestion, “blocking out the mountain” and heritage – again, the “conservation” argument concealing conservatism. This plays itself out across the desirable parts of Cape Town, from Newlands – where nimbys in houses object to new blocks of flats and get nostalgic for the days of the white group area; to even Bo-Kaap, where similar nimbys in houses object to new blocks of flats and get nostalgic for the days of the Malay group area.

The result is a city where the supply of new housing is suppressed and the cost of established housing stock skyrockets, much as it has done in Cape Town. Our winning bid was all set to address this.

We planned to complete the inner viaducts of the flyovers at a height of four storeys above natural ground level, allowing for a four-storey plinth of parking, which is lined with an urban “crust” of three-storey walk-up apartments – i.e. affordable housing.

Between the new inner viaducts, we engineered an 18m wide opening, through which can rise upmarket and midmarket residential towers ranging in height from 63m to 123m to 143m, which is a height consistent with the other tall buildings in the Cape Town city centre. The towers were envisaged as tall, svelte and elegant – with substantial height variances and large spaces between them.

Our radical social proposition was to create integrated communities within the self-same high-rise residential towers. Rather than to create low-rise and mid-rise ghettos on the Foreshore, our proposal uniquely sought to integrate the affordable housing units into the very same buildings and structures as the midmarket and upmarket housing – where rich and poor not only share the same neighbourhoods but actually inhabit the very same buildings – which is the most potent possible gesture available to us in reversing the apartheid legacy.

The streets were to be upgraded in order to form a common agora for all classes. This is not Disneyland. We were attempting something braver here. The future for the Cape Town City Bowl simply has to be tall and dense if it is to equitably accommodate more people. Elegant and sculptural high-rise towers offer a Hong Kong or Singapore-like future for our city, and therefore the opportunity for ordinary citizens to have a real stake in central Cape Town – even if that stake takes the form of a 30 square metre bachelor studio.

Dignified new urban environments were planned for under the Freeways. Artist’s Impression © 2017 Robert Silke & Partners

It is unsurprising that most of the unsuccessful bids had in common the nostalgic ambition to demolish the freeways in some form or another. Perhaps the most well-funded of these was the proposal (known as “Urban Dynamics”) to erect a 100-storey circular apartment block in the shape of a giant Ferris wheel, and to sink the freeways underground – aping what the city of Boston had attempted in the 1990s.

The budget for burying the Boston Freeways was $1.5-billion dollars in 1990 and escalated to $15-billion at completion. With interest, the total bill came to $24-billion. The big dig bankrupted the City of Boston as well as the Commonwealth of Massachusetts – and is regretted to this day. The tunnels failed and workers died. Commuters died. Boston is a city mired in debt and regret.

Closer to home, we all remember how Gautrain was budgeted at R3.5-billion and ultimately cost us R35-billion. While the Urban Dynamics bid was to cost the City of Cape Town untold billions, our bid was entirely self-funding and therefore of no cost to the City at all.

It was nevertheless widely reported in the local press that the Foreshore Freeway Bid Evaluation Committee Member, former commissioner of Transport for Cape Town, Melissa Whitehead, was dismissed from the committee for allegedly showing favour towards the Urban Dynamics Bid – while showing bias against our own. Bid auditors Moore Stephens reported that Whitehead claimed to be representing the views of her political superiors. After internal investigations, the Bid Evaluation Committee was accordingly reconstituted without Whitehead and, based on the merits of the points scorecard, our bid was announced as the preferred bidder – though perhaps “met lang tande”.

While we were the preferred bidders and winners of stage one of the tender, we were under the distinct impression that we were not the political favourite. It remains a mystery to us that the City, having eliminated the biased committee members and having self-corrected its own process, would still not be satisfied with the outcome. Our team had heard rumours from the outset of the tender that the City already had a preferred unsolicited bidder, but we were assured by the City that this was not the case.

While the tender brief seemed clear to us that Cape Town was in crisis and needed to complete the freeways as a matter of urgency, and at little or no cost to the City, most of the bids were rendered dysfunctional and non-responsive due to their failure to address that fundamental brief, one that seemed clear and unambiguous to us. It is bewildering to us that the entire process should have collapsed on the strength of a procedural appeal on the part of the Urban Dynamics consortium, on the astonishing basis that the RFP was “void for vagueness”.

The City of Cape Town has missed its (perhaps last) opportunity to complete the freeways timeously, and thereby to address the draining traffic congestion that paralyses the City’s economy. More important, we miss the opportunity to expedite a significant contribution to the provision of well-located affordable housing which is desperately needed to transform our gentrified city centre.

Ultimately, Cape Town will be missing out on substantial foreign direct investment (around R16-billion escalated value) and a significant injection into the design and construction industries at a time when building contractor liquidations are on the rise.

Capetonians should be deeply troubled by the message this gives to prospective local and outside investors and developers in respect of the City’s competence.

The City has scuppered a catalytic project that would reignite the local economy and create jobs. It is precisely now that bold steps are needed to invest and reignite the city’s economy. This is especially true when the City is not required to fund the project.

We know ours to be the only proposal that can complete the freeways and improve their capacity without shutting down the city for weeks, months or years. Decades even. An event from which we will never recover. To this end, we assembled a team of veteran transport, traffic and roads engineers with intimate history and knowledge of the past, present and future of the Cape Town highway system. The team represents an ephemeral and precious commodity that cannot easily be reconstituted and should not be taken for granted.

Even if the City now intends to restart this process, from scratch, as they say they now do, market conditions have changed and the City’s procurement methods are discredited. The bidding teams are out of pocket for tens of millions of rand, and there is no guarantee that the same bidders will have the appetite to bet another R10-million on the City’s teetering tender processes. The intellectual capital concentrated in our team cannot simply be taken for granted to be available for the rerun.

For all of its natural beauty and its skin-deep luxury, Cape Town is a city with an incomplete urban environment. In Steven Watson’s 2001 prose and poetry anthology, A City Imagined, Cape Town’s urban fabric was compared to that of Algiers, likened to an open wound, with an incomplete Foreshore, a still vacant District Six – and of course the amputated missing limbs of the incomplete Foreshore Freeway system.

Whether this process is restarted from scratch – or whether it is abandoned altogether – the process of completing our broken city has been set back for years, if not decades. DM

Robert Silke is Director of Robert Silke & Partners, architects of the preferred bid for Cape Town’s abandoned Foreshore Freeways tender.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider