The triumph of history

Jeremy Vearey – activist, teacher, gang-buster, top cop with the heart of a poet

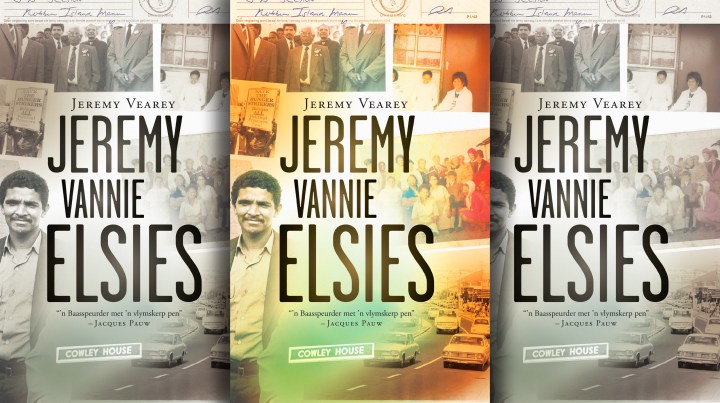

There is a generation of South Africans, now in their 40s and 50s, who cut their political teeth in the mean and violent streets of Cape Town during the final years of white minority rule in the 1980s. Current WC Deputy Commissioner of Detectives Jeremy Vearey was one of those young people whose lives were inexorably bound to the Struggle and who also spent time incarcerated on Robben Island. With the heart of a soldier and the soul of a poet, Vearey has just delivered his memoir, “Jeremy Vannie Elsies”, an account of a life rich with resistance, poetry, politics and revolution.

“Ek maak en gooi self my dice, en daa waar’it val, land dit soos ek dit wil. Maar by the way, soe in die verby, kaantie, wies jy?” – Jeremy Vearey

(I make and throw my own dice and where it falls, I have willed it. But by the way, just in passing, just who are you again?) – Jeremy Vearey

The final lines of Vearey’s memoir quoted above are a riff on one of academic, essayist, author, playwright and poet Adam Small’s (1936-2016) iconic poems “Die Here het gaskommel” (God Threw the Dice). In Small’s poem, contained in his 1961 anthology, “Kitaar My Kruis”, he writes “die Here het gaskommel/en die dice het verkeerd geval vi’ons/daai’s maar al” (which loosely translated reads, “God threw the dice/and the dice turned up wrong for us/that is all).

The “us” Small refers to are those South Africans who were classified by the apartheid regime as “coloured”. Small was also the first perhaps to write in what has become known as Afrikaaps, the root of what later was expropriated and claimed, by white speakers of the Dutch dialect, as an original language, Afrikaans, in May 1925.

It was Afrikaans, among other issues, that provided the spark that lit the flame of the 1976 uprising of black youth in Soweto when the then government attempted to force it as a language of instruction for all subjects in all schools in the country.

Vearey was 14 when the townships of Soweto erupted but he would have to wait a few more years, until the 1980s, before the currents of resistance swept him and his comrades along an inexorable trajectory towards freedom and the dawn of democracy in the early 1990s.

But not without cost.

For this Vearey, as well as several other Cape Flats activists, were sentenced in 1988 to jail terms of between 10 and 15 years on Robben Island. This after being subjected to torture and torment by the notorious security police dished out regularly to detained activists at the time. In the book Vearey details what was done to him in the name of white South Africa and it is shameful.

Later Vearey, after joining the SAPS, would encounter some of these old members of the police “force” who now were “colleagues”.

While life in prison on the island for the leadership of the ANC and other political formations has been well documented, Vearey reveals what it was like for ordinary UmKhonto we Sizwe members, known as the Cape Town 15, and including Ashley Forbes, Anwa Dramat, Peter Jacobs (recently appointed head of Crime Intelligence) and others.

What enabled these young men to survive the dire conditions was the discipline of their political training, their selfless comradeship and the determination to remain focused, positive and sane.

While the political leadership of the ANC and other “banned organisations” was released to great fanfare and celebration, Vearey sets out what it was like for other political prisoners who were not as high profile and who were released much later to a country in the grip of Mandelamania.

His account of how a bewildered group of released Robben Island prisoners had to walk to the Grand Parade to phone for a lift is heart-breaking and extremely moving.

In the very act of writing this nuanced, funny and rollicking biography of an eventful life growing up classified as coloured in Cape Town in apartheid South Africa, Jeremy Vearey has wrenched his personal narrative from the confines of the politics and madness of the time, to claim not only his own life but the history and the lessons of this tumultuous epoch.

Another poet who inspired both Small and Vearey is Afrikaans writer NP Van Wyk Louw, regarded as one of the greatest South African thinkers, intellectuals and writers. It was Small who once opined that had Van Wyk Louw written in English he would most certainly have won the Nobel Prize for literature.

On a plaque affixed to the Taal Monument in Paarl and celebrating Afrikaans, are these words from Van Wyk Louw; “Afrikaans is the language that connects Western Europe and Africa… It forms a bridge between the large, shining West and the magical Africa… And what great things may come from their union – that is maybe what lies ahead for Afrikaans to discover. But what we must never forget, is that this change of country and landscape sharpened, kneaded and knitted this newly-becoming language… And so Afrikaans became able to speak out from this new land… Our task lies in the use that we make and will make of this gleaming vehicle…”

And boy has Vearey made a meal of it.

It is not only the telling of the tale of his life but Veary’s extraordinary capacity to take the language, shake it by the scruff of its neck and to shape and bend it to his will that truly renders it a “gleaming vehicle”.

Vearey, being the old revolutionary he is, has used the very language of the oppressor to free himself. And Veary’s literary flair, by the way, is thrilling.

There are many of us who were forced to learn to speak and read Afrikaans and if there is a poetic justice to it all, it is that today we are able to read and enjoy Veary’s remarkable book. The publishers should consider translating the work into English so that it can reach a wider audience of young South Africans who need to know the extraordinary history, particularly of the Western Cape and the activists of the 1980s.

Vearey quotes often from Van Wyk Louw and uses the author’s work to allude to much deeper currents that run through him still but which he cannot write about.

“Jeremy Vannie Elsies” (Tafelberg) begins with a poignant portrait of how the divided country he found himself in came to reveal itself to his six-year-old self. He describes how the barefoot boy he was, leapt with wonder from a double-decker bus he was travelling in accompanied by his seamstress mother as it reached its stop in Parow.

Little Vearey, clearly a bundle of energy, curiosity and derring-do, rushes towards a subway trailed by alarmed adult voices trying to stop him.

“The boy, who has sprinted into the subway with a blind innocence, suddenly realises he is alone in the dark tunnel. Then everything happens quickly. He feels a blow to his stomach and collapses, gasping, to the ground. Somewhere, between the tearless crying, he feels a huge hand grabbing his ear and dragging him to the exit.”

Through the pain and the tears little Jeremy hears someone scream “Hotnot, jy hoort nie hier nie! Fokof na jou kant toe!” (Hotnot, you don’t belong here. Fuck off to your side).

In the bright light at the end of the tunnel, Vearey spots the silhouette of his mother, Annette, and a posse of women, hands on their hips, confronting and threatening the white man, ordering him to let the child go.

It is Veary’s conscious birth into a world where he is regarded as “less than” and he is having none of it.

From here Vearey sketches the backyards, the pondoks, the grey dusty streets and the houses of his youth. There is the constant moving, the difficulty shooting any roots because of economic or political circumstances which remove agency from people’s lives.

But everyone around the Veareys is in the same, leaky, second-class apartheid boat.

These are places populated by strong characters, his grandparents, his parents, his brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces and extended family, all trying to make do. There are the gangs, the violence, the religious fervour of believers, the thieves and the drunks.

Vearey’s is a tale told with love, fondness and sadness as he recalls how his father teaches him and his brothers how to man-up and sort out differences using their fists. But once blood has been drawn, the fight is over, and no grudges must be borne.

Vearey at first trains to become a teacher and finds himself in the hotbed of student politics in the Western Cape of the 1980s. He is soon recruited to join MK along with many others and in this section of the book Vearey sketches the violent and chaotic currents that swirled across the country and which dragged him along.

The book traces Vearey’s journey from activist, teacher, party animal and flirt, to underground MK soldier, prisoner and later protector of Nelson Mandela.

This is not only a book about a life, politics, war and resistance, it is also a book about love; love of fellow human beings, love of family, love of country and love of liberty. It is a book about a remarkable, unique and unorthodox South African, who continues to contribute to the “greater good” of this country as one of its top cops.

If you can speak and read Afrikaans please do get Vearey’s memoir. If you can’t, well, sorry for you. DM

This article was amended at 11.25am on June 20, 2018, to correct an earlier spelling error.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider