OP-ED

ANC recovery and democratic recovery – not the same thing

From the time of his election Cyril Ramaphosa faced constraints, with an unstable base, and some in the ANC possibly working for him to fail. Over time the Ramaphosa leadership has acted boldly, making significant decisions. Having lived through the Zuma period, citizens need to be vigilant against any relapse and rely not only on their representatives but also their own power.

This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s website: polity.org.za

There is no doubt that very many South Africans feel more positive about political developments since the election of Cyril Ramaphosa to the ANC presidency in December and a few months later to the State Presidency. The Jacob Zuma presidency had come to take on nightmarish qualities, with state monies stolen to the tune of over R100-billion through State Capture (by the estimate of Pravin Gordhan). Admittedly, much of the evidence and scale of state capture only came to light later, so that the picture remains incomplete and the damage may be greater than current estimates.

But what needs to be remedied cannot be measured purely in financial terms. The Zuma era, although he may not have conceptualised it in systemic terms, represented a broad project with political, constitutional, cultural, ethical, gender and broader social qualities, that also manifested a high tolerance of violence. All of these signified opposition to efforts to achieve social transformation, that would enhance human dignity and well-being.

What has happened in the last nine to 10 years has shocked many who had never expected the country to take such a turn. There was a moment, in the 1990s when South Africa was seen by many as a country which was in many respects exemplary. It had an exceptional first president in Nelson Mandela. It had been able to resolve many of its differences to the point where democratic elections could be held as a result of a process of negotiations between previously warring parties. It developed an advanced constitution, in some ways more progressive than any other in the world. In general, despite some lapses even in the early years, many cherished the hope that the “new South Africa” would be a democratic and constitutional example for many others struggling for freedom in the rest of the world.

In the early years of South African democracy there was some fear that a coup would be attempted and some leading elements of the security forces, retained from the apartheid regime were removed to safeguard the constitutional order. Paradoxically it was not these people nor other former members of the apartheid regime or other right-wing forces that undermined the hopes that were cherished for the new democratic state.

Scandalously, it was actions of the oldest liberation movement on the continent, one of the oldest in the world, who had produced leaders and members that were envied by political movements around the world, the ANC itself, that undermined these achievements. This was an organisation with a developed body of understanding of its approach towards liberation. This was a movement, many of whom had made great sacrifices and endured torture and death in order to secure freedom. But it allowed Zuma to destroy many of its gains and some of its leading figures enjoyed some of the fruits of his corruption.

It was the ANC and its tried and tested allies, the SACP and Cosatu who knowingly fostered the leadership of Jacob Zuma, as the alternative to the allegedly over-centralised and conspiratorial rule of President Thabo Mbeki. Mbeki may have had faults that needed to be remedied and opposing his attempt to win a third term as ANC president could reasonably have been defended. But on what basis can it be said that an alternative to these real or alleged flaws resided in Jacob Zuma, whose record displayed dubious qualities, a man who was already in the midst of allegations of corruption and rape?

In order to erase any blemish that may have hung over a Zuma presidency a special committee was established, to find ways of quashing the charges against Zuma. The charges were indeed withdrawn, without going to court, in a decision by the then acting head of the National Prosecuting Authority, that was opposed by others in his prosecuting team. But the charges have now been reinstated and that is the prosecution that Zuma now faces. (There may well be many other charges deriving from State Capture.)

Not only was Zuma foisted on the ANC and the people of South Africa through the power of its prime leaders and allies, but it took many years before any of them voiced disquiet over much of what Zuma had done. And the reservations that they have come to voice do not represent a full admission of the wrongdoing that the Zuma era represented, for it was not simply corruption or State Capture.

The importance of noting this resides in what it means to address the Zuma legacies. If the current leaders do not articulate all that was part of the Zuma era, we cannot be sure that all of its qualities will be addressed and not repeated partly or in its totality-including, the violence, the cultural chauvinism and essentialism, the hyperpatriarchy and other anti-democratic features.

Many people were relieved at the election of Cyril Ramaphosa and polls suggest that he has won the confidence of very many people. As is well known the circumstances of Ramaphosa’s election imposed constraints on what he could do, having been elected as ANC president by a very narrow margin, together with three others -in the “top six” who were either supporters of Zuma or located in an ambiguous position. There is no need to repeat that some appointments to cabinet have filled many with disappointment. Clearly Ramaphosa had to act in a manner that ensured stability in his support base by making concessions in appointments to those who had been compromised under the Zuma period or who have in fact been fingered in various allegations or investigations into corruption. It may be undesirable or repugnant to see some people in top positions, individuals who are notorious in various ways, but Ramaphosa was not in a position to act in a “pure environment” and do exactly what he may have considered ideal.

What is significant however is that despite this uneven backing, Ramaphosa has managed to achieve a great deal and has actually led the ANC and the country, even before becoming state president. There has been little of the “sitting” on reports that characterised the Zuma period. Ramaphosa has been able to achieve movement away from irregularity and has created the impression of determination to put the broken pieces of South Africa back together again, by appointing ministers who have demanded the reconstitution of boards and prosecuting the multiple wrongdoers.

The gains have been ambiguous insofar as the depth of the rot, especially the capture of law enforcement agencies has meant that some of what has been done has been contradicted by other actions. Thus, charges against Zuma have been reinstated, but the Guptas and Duduzane Zuma despite being suspects, were allowed to leave the country. There is also the institution of questionable charges against some of the SARS “rogue unit”.

How do we ensure that the Ramaphosa “new dawn” remains on course in the sense of strengthening legality and enhancing democratic life, hopefully going beyond simply returning to what things were before Zuma? It is important that we, as citizens, do not allow the fate of the country to be determined by the ANC alone, especially the restraints demanded by the support base that may or may not be needed to secure Ramaphosa in the position of president. That cannot be allowed to hold the country and its interests to ransom.

One of the lessons of the period from which we have not yet recovered is that we as citizens cannot leave politics to the politicians alone, those of the ANC or other parties. “Leaders have to lead”, Nelson Mandela used to say. But that does not mean that “followers” or those they represent are a passive mass that simply observe what is done.

We have to ensure that the country recovers its promise. We need to make sure that there is not slippage, that phenomena like the collapse of governance under the weight of corruption in North West are brought to heel and remedied. In some cases, sections of government will be sufficient to ensure that this happens. But there is also a need for continued action by sections of civil society, litigating and also acting in a range of other ways in order to keep democracy and transformation on course as part of a broad emancipatory project whose scope is not yet fully imagined.

Beyond this, there needs to be a political mass, a political existence with substantial weight that resides outside of parliamentary politics. That is not to say that it is only found in the streets or in demonstrations of different kinds. It may be in organised form in a range of places and act in a range of ways. But that popular and civic force is needed. That source of power is required in order to influence the direction the country takes.

That is not to say that there is a self-evident direction that the country must embark on, merely requiring endorsement by large numbers. Part of the need for this source of power to be mobilised and organised is in order that those who are outside the formal political terrain need to have a space where they can debate democratic and transformational options amongst themselves and also with professional politicians. The extra-parliamentary terrain, civil society, professional bodies and social movements amongst them are likely to have a range of political orientations. These all need to be part of debate on the present and the future, especially debate that ensures that the country does not again veer “off course”. It also needs to be part of ensuring that we explore all the ways that can determine that the fullest potential of our freedom is realised. That can only be achieved if we are all involved, not simply those we choose to represent us every five years. The ANC may lead this process, but it may well be that other forces will take the lead or act together with the ANC, that is, if all who have an interest in realising the country’s full potential involve themselves in various ways in making freedom happen. DM

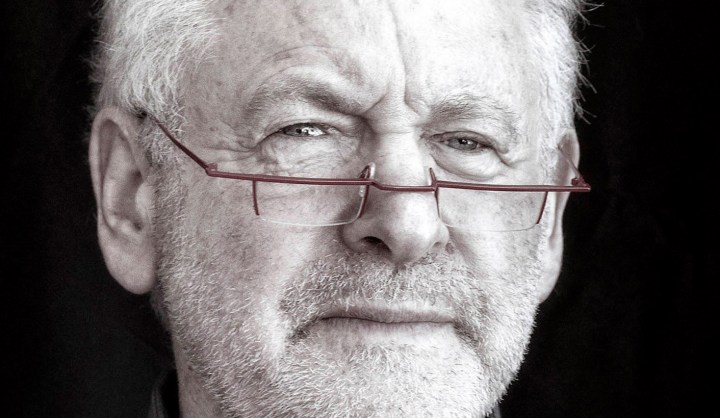

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. He is a visiting professor and strategic advisor to the Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg and emeritus professor at Unisa. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His prison memoir Inside Apartheid’s prison was reissued with a new introduction in 2017. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his Twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

Become an Insider

Become an Insider