SPECIAL REPORT

Government surveillance of social media is rife. Guess who’s selling your data?

If you are tweeting or posting about a “security threat”, law enforcement can fish you out of the ocean of the world’s 2.6-billion social media users. Using special surveillance software, they can gather posts from platforms to identify you, and walk right up to your front door. Governments buy this data from surveillance companies, who in turn buy it from social media companies. But security threats are what governments decide them to be. These include certain protesters, non-profits and journalists. In a country where intelligence services are known to commit corrupt surveillance practices, can the law protect us from misuse?

There’s a reason why Stephen King’s IT first appears as two blazing eyes in the darkness, and why it scares the crap out of you every time you watch it. It triggers the instinctive fear of the hunted. It’s a hard-wired reaction that’s allowed our species’ survival. A successful predator sees you long before you see it. By the time you do, it’s too late.

But, in the world of the virtual, the visceral is lost. Removed from flesh-and-blood face-offs, we visibly share our lives on social media. And social media giants collect vast amounts of data about us. For an example, log into your Facebook account. You can download your personal information – over 50 data categories – stored since you first joined. Posts, messages, tags, pokes, searches, the friended, the unfriended, login locations, facial recognition data… For a complete list, go here.

Social media companies assure you that your information is protected, even if your data is sold to marketing companies, since marketer’s shouldn’t able to identify you. Generally, advertisers tell the social media company what demographic they want to target, and then the social media company will ensure that the advertisements find you if you are part of that demographic. This is how specific adverts land on your Facebook page. Bottom line: a salesman or stalker won’t visit your house.

But that doesn’t mean the state won’t. And that includes the South African government.

To find you, intelligence services needn’t hack your social media account, or get a court order to force a social media company to release your private data. What they need are your public Twitter, Instagram or Facebook posts, and the right social media surveillance software.

And, just as social media giants sell your data to marketers, they also sell it to surveillance software companies, who then sell it on to government intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Ultimately, the state can use your public social media posts to identify you and walk right up to your door. This outcome is very different from being targeted with advertisements.

To understand just how invasive the technology can be, it helps to take an in-depth look at an example of software being used in South Africa, namely Media Sonar. The product is designed and sold by a Canadian firm by the same name. The DM has established that the software is also being employed in South Africa to assist our intelligence services.

Media Sonar’s strength lies in its ability to monitor social media activity within a specific geographic area. Company marketing materials uploaded to the US’s National Security Internet Archive in February 2016, assert that Media Sonar can monitor Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Picasa, YouTube, Flickr, FourSquare and Vines.

The software aims to identify security threats. Threats can be whatever governments decide them to be. In South Africa, they also include protesters, non-profits and media agencies that speak out against the ANC.

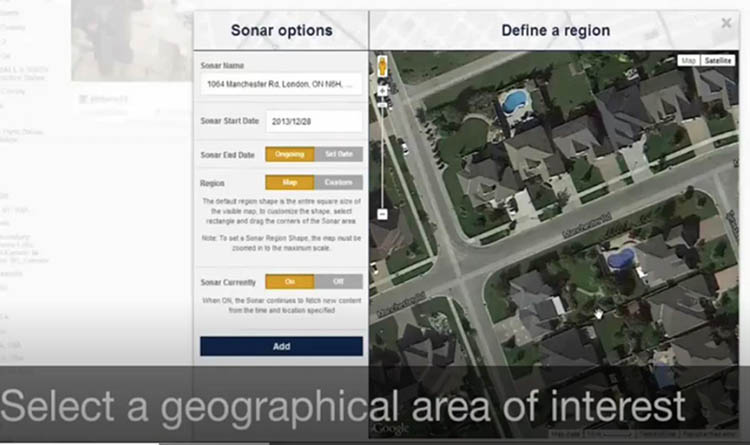

Media Sonar allows for “geofencing”. You can cordon off, by specifying GPS co-ordinates, an entire region, town, neigbourhood, or campus. You can also pinpoint a single address. Then, the public social media posts of people who are in the geofenced space can be picked up.

Geofencing allows Media Sonar to search for social media posts being made in a specific geographic area. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar marketing presentation)

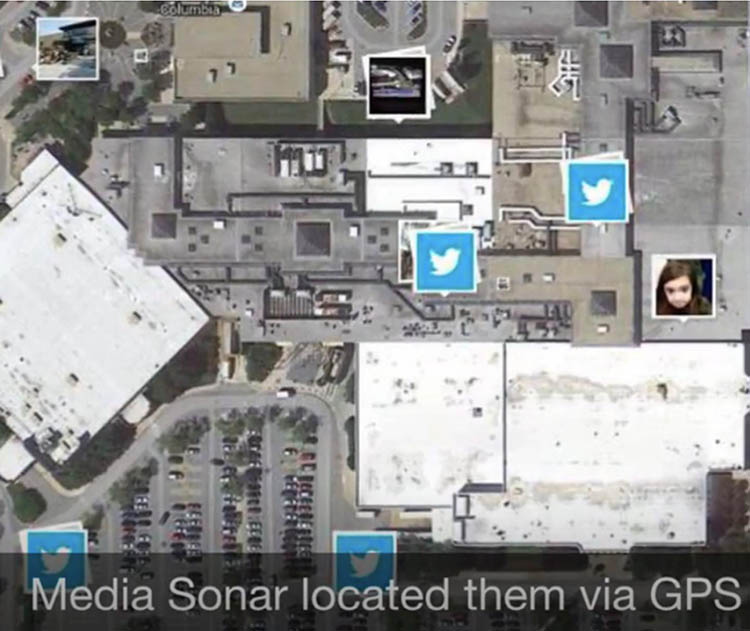

The Media Sonar dashboard provides a bird’s- eye view of the area in which people are posting to social media. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar marketing video)

You may think that you are safe if your geolocation services are turned off. Not quite. Let’s take Twitter. According to their website, only 1% to 2 % of all tweets are geotagged – in other words, people add their GPS co-ordinates to the post as they Tweet.

But this is not the only way to establish a person’s whereabouts, even if only approximately.

Former US army colonel Rob Guidry is the founder of SC2 Corp. The company sells a product similar to Media Sonar’s. In March 2016, Guidry delivered a talk at the US’s Army Cyber Institute, addressing role players in government, military, and industry. He explained that, when you publicly post on platforms like Twitter or Instagram, geospatial enhancement makes it possible to establish a target’s approximate location even if their phone’s geolocation service is turned off.

“You’ll hear people say, ‘3% of tweets can be geolocated’. That’s actually not a true statement. About 15% can be geotagged – only 3% of them were geotagged at the instance of the tweet itself. So the answer is, down to the physical address – 3%. Down to the general vicinity of the area of the town, you’ll probably get around 15%, down to the city you can actually get around probably 70% to 75%. And that’s going to be based off of the author’s profile.”

A third, and very accurate way to locate someone, is through Google’s geospacing. When your geolocation service is turned off, your mobile must still connect to cell phone towers and WiFi hotspots around you. Their locations are known. The farther you are from a tower or a WiFi hotspot, the weaker the signal to your phone. The closer, the stronger. This signal strength can be used to determine your distance from each WiFi spot or tower, and then your location can be triangulated. The more WiFi spots or cell towers your phone connects to, the more accurately your location can be pinpointed. The DM could not establish whether or not this method was used by existing social media monitoring software.

An aerial view illustrates exact locations of Twitter users as they are posting, based on the phone’s GPS co-ordinates. However, there are various ways to establish your location. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar marketing video)

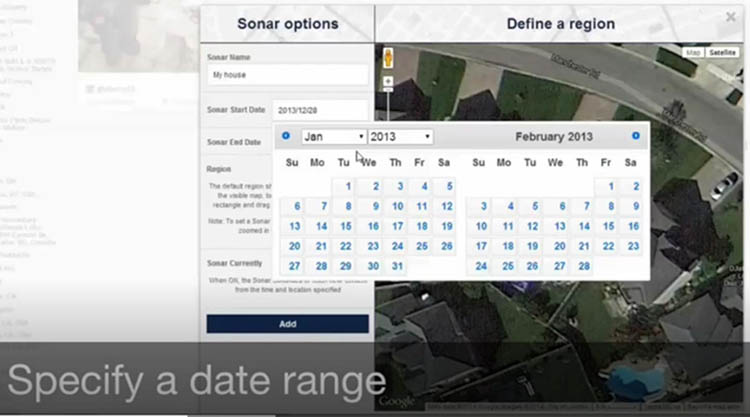

Once the software is programmed to monitor posts (like Twitter or Instagram) within a specified area, it can also be programmed to gather posts occurring within a specific time frame. Thus, an area can be monitored before, during, and after an event. There is no limit to the amount of data that can be gathered, and it can be stored indefinitely.

It’s possible to specify the period within which to search for posts. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar marketing video)

After cordoning off a geographic area and time frame, searches can start. Keywords for searches are then developed (at times in a collaborative effort between law enforcement and the surveillance company) to locate posts from potential witnesses or perpetrators. The software will find what’s written in tweets and hashtagged items.

An example of keywords used to search social media data to identify people of interest. This list was obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union through court processes

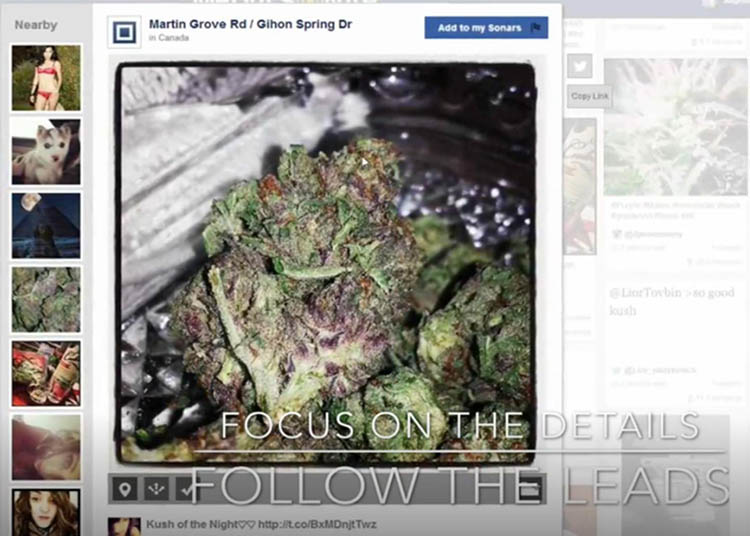

Keyword searches then reveal posts that may be relevant to intelligence services. Below is a an example of the Media Sonar dashboard posted on Twitter in 2014 by a police officer during a Media Sonar workshop. It shows posts from Instagram, a subsidiary of Facebook. There are around 800-million active Instagram users worldwide. The app allows users to post photographs which are visible either to the public, or to followers only, depending on the privacy setting the user chooses. It’s these public posts that are detected by Media Sonar.

A user can turn on their phone’s geolocation service, and the app then produces a choice of locations – usually popular ones within the vicinity, like a beach resort or restaurant. The post can then be shared to Twitter, Facebook or Tumblr. Media Sonar will also show you who shared what with whom, and when, so it becomes possible to map your social circle and your movements.

An example of the Media Sonar dashboard. It was posted on Twitter in 2014 by a police officer attending a Media Sonar workshop. It illustrates how even citizens not involved in crime and terror activities are caught in the surveillance dragnet

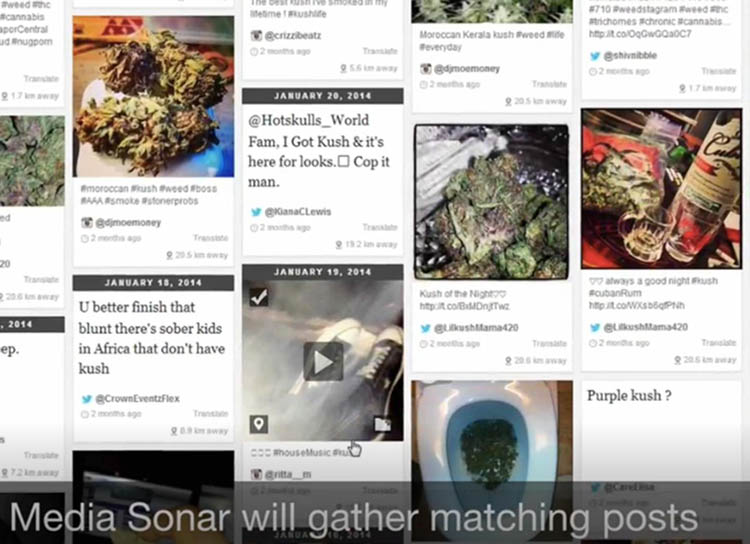

After people are located within a certain area, the software can further refine the search to reveal individual users of potential interest to the authorities. In the example below, a key word search relating to marijuana was applied.

Keyword searches find user profiles that intelligence services would otherwise have missed. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar marketing video)

Finally, Media Sonar can be used to find individuals, as illustrated below.

Here, the Media Sonar search zoned in on what may or may not be an unusually attractive drug kingpin with a puppy. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar marketing video)

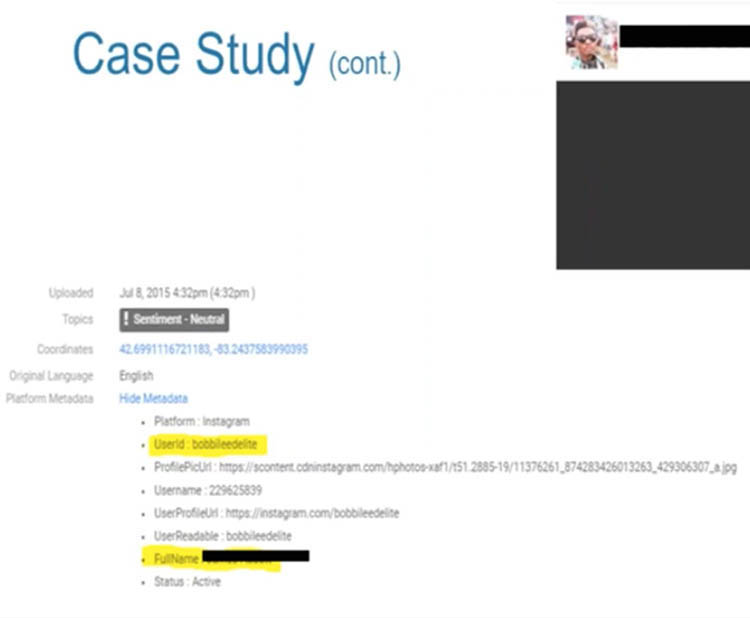

Media Sonar also shows intelligence services a user’s metadata. This is data about the post, and includes the account holder’s GPS coordinates at the time of the post, their full name (if that person provided their real name upon signing up) and when post was made. It also tells the surveillance personnel the user’s “sentiment”. This is derived from text and emoticons in the posts. The software can also describe the dominating sentiments within a crowd.

Media Sonar can be used to identify individuals. This data can ultimately help law enforcement to locate the person if they are considered a witness or suspect. (Extract from a 2016 Media Sonar presentation)

Once an individual of interest is identified, he or she can further be targeted by the use of “dummy” accounts. This feature of Media Sonar allows police to set up a fake account in order to go undercover.

False accounts allow the Media Sonar user to do undercover operations on social media

In the United States, civil society has taken issue with law enforcement using software like Media Sonar. Already in December 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California had announced obtaining documents revealing that Media Sonar was using data from Twitter, Instagram, Picasa, You-Tube, Flickr, FourSquare and Vines for law enforcement surveillance purposes, and that it was probably being used to spy on protesters.

The following year, ACLU released a report revealing the relationships between surveillance companies, social media outlets, and the police. It was based on thousands of documents that ACLU lawfully obtained from police through the Californian Public Records Act. Following pressure brought by ACLU, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram announced that they would restrict surveillance companies’ access to their data. Since then Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have explicitly stated that their data is not to be used for surveillance purposes.

Despite this, companies like Media Sonar and many others like it continue to operate.

One thing that social media monitoring companies usually emphasise, is that they can only analyse posts that you made public. This usually serves as justification for monitoring, collecting, and analysing data without legal oversight. At the end of his presentation, Colonel Guidry explains: “The system will bring data to you, but that data that it brought to you was data that, if you would’ve typed in the right character string in the Google Chrome browser on the right day… you would have found the information yourself. It’s all PAI – publicly available information.”

Currently, this is how intelligence services in South Africa approach the matter too, as one industry expert who spoke off the record explains: “From a monitoring point of view, the minute it’s out in the wild, it’s considered published, so you don’t need a warrant to specifically look at somebody’s Twitter or Instagram profile, or whatever the case may be.”

Regulation only kicks into action, says the source, once authorities require information that the user didn’t make public. For instance, once a potential criminal’s Twitter handle has been identified, intelligence services may want to find the email address or telephone number associated with the account. For this, says the source, intelligence services need to apply through processes provided for in the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty between South Africa and the United States. This treaty allows the two countries to exchange information about investigations happening in both or one of the countries. This process is facilitated by the Justice Department. Says the source: “There’s no other way to get that stuff because it’s not publicly viewable.”

In addition, should SA’s intelligence services wish to set up a false account to go undercover, that would be treated like any other undercover operation, and be regulated by the Criminal Procedures Act.

But stricter data protection regulations are on the way. Alison Tilley is an attorney and head of the advocacy department of the Open Democracy Advice Centre. She’s also a member of the South African Law Reform Commission Project Committee on Data Protection. She says that storing and analysing social media data is not a free-for-all, thanks to the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI).

Tilley explains: “So if you gather, process or store personal information, you are subject to the provisions of POPI.” Tilley says that your social media posts may be public, but that doesn’t mean they’re not personal and therefore protected by POPI.

“It’s not a question of it being public. It’s a question of why you put that information up there. It’s personal information which you make available. You do that because you want to make a comment on something. If somebody then takes that information and they record it and they then start to mine that information, that then becomes the processing of that data.”

So, how does POPI protect people from social media surveillance? Guidelines to POPI published by the Law Society of South Africa earlier this year provide some answers.

One restriction, is that your data should not be stored for longer than necessary.

Another, is that the purpose of processing the data must be clearly defined, and must be related to the intelligence services operations. Thus, if your public posts are collected and analysed for surveillance, there would have to be a good reason.

Says Tilley: “If you (as a social media surveillance company) gather it (personal data) off Twitter, and then sell it on to somebody, I think you can be sure that the people who posted that information did not consent to that. So the question would be, what is the purpose in doing that?”

The government (or companies appointed by the government) may process personal information if the purpose is to “safeguard national security” or for “the investigation and prosecution” of crimes. But this is subject to the establishment of “adequate” legislative “safeguards” to protect personal data. The onus is on our intelligence services to draw up such regulations.

In practice, however, social media surveillance in SA remains largely unregulated.

POPI, although it was signed into law in 2013, is still to be implemented, and special regulations pertaining to data processing for surveillance purposes are yet to be made. For now, you just won’t know if the clown is watching you. DM

This story was commissioned by the Media Policy and Democracy Project, an initiative of the University of Johannesburg’s department of journalism, film and TV and Unisa’s department of communication science

Heidi Swart is a journalist who has extensively investigated South Africa’s intelligence services

Become an Insider

Become an Insider